The Miniature Rooms of Narcissa Niblack Thorne

The Thorne miniature rooms are the brainchild of Narcissa Thorne, who crafted them between 1932 and 1940 on a 1:12 scale. Incredibly detailed and...

Maya M. Tola 9 January 2025

Early in his career, American architect Frank Lloyd Wright – the famous pioneer of the Prairie School style at the turn of the 20th century – experimented with a host of organic designs. He was a long way from fully developing his more geometric, abstract patterns, but nonetheless got the chance to try them out on a fledgling project.

In 1897, the Luxfer Prism Company hired Wright to design decorative patterns for their glass tiles. The prismatic glass appeared on the American market at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, IL, from Gustave Falconnier. It promised the opportunity to provide light to dark buildings at a time when electricity was expensive (and often dangerous).

Natural light was also hard to come by in urban environments where alleyways and high rises blocked out most of the sun. The prismatic glass was ribbed on one side – covered in rows of miniature prisms, often 21 to a 4 x 4 in (10.16 x 10.16 cm) tile – so that light could enter from an oblique angle and be redirected into the room beyond. They were often found lining storefronts and office buildings.

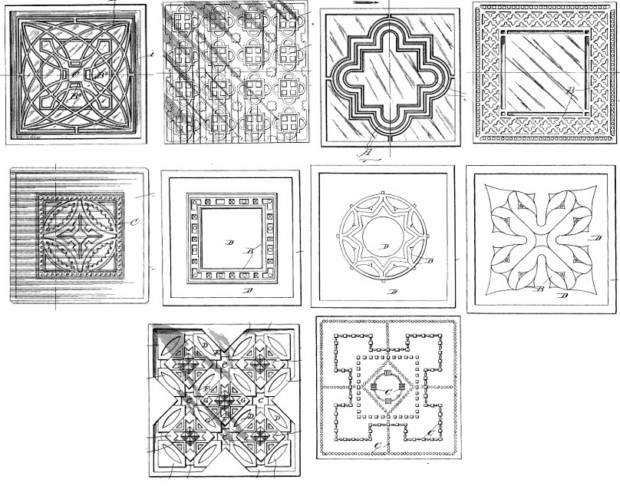

Wright himself patented around 40 different designs, many of which had organic origins. However, the only one that ever saw daylight was his “flower” design. These provided a pleasing ornamentation to a building’s façade but didn’t improve the quality or quantity of light entering.

One can see that Wright’s designs would remain an influential part of his oeuvre. His windows – or, as he called them, “light screens” – eventually became the crown jewels of his architectural designs. They often reflected forms visible in nature, such as Lotus flowers (in his home and studio in Oak Park, IL). The same home contains a patterned screen that covers a light in the dining room which is meant to resemble a canopy of oak leaves.

Despite his later success, Wright’s prismatic tile designs didn’t seem to catch on with Luxfer (besides the “flower”). Still, his royalties from that single patent would help him fund a new studio in Oak Park. Here he would design some of his most famous buildings, such as the Unity Temple and Robie House.

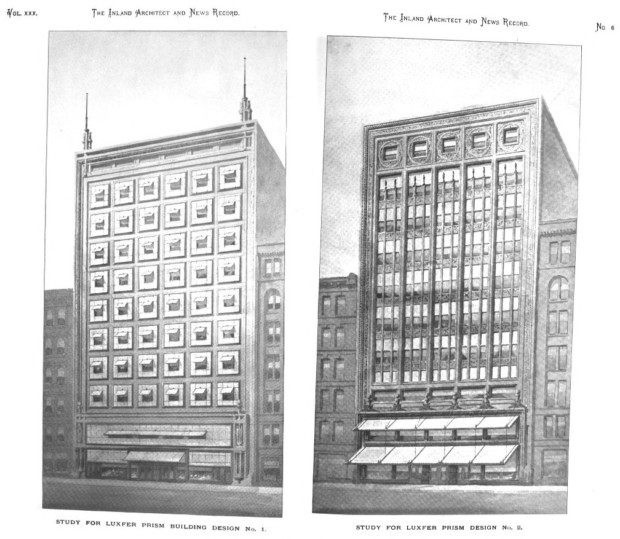

While at Luxfer, Wright also prepared sample designs of an office headquarters for the company. While these never came to fruition, the drawings have been considered by some to be of great architectural significance. A pioneer on many fronts, Wright, even in his unrealized ideas, was a manufacturer of many precursors to modern architecture.

Today, Luxfer Glass is now Luxfer Gas Cylinders and Wright’s tiles have become popular collector’s items. Some still remain on older structures in and around Chicago, many having been covered by canopies or later construction and revealed during renovation.

Wright’s legacy lives on, clearly, as he is one of architecture’s most celebrated figures, though many of his patterns and intricate ideas lay unused in the US patent office. But, for a short while, he was the jewel of Luxfer Glass, as Luxfer was the jewel of the urban storefront.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!