1. Utagawa Hiroshige, The Plum Garden in Kameido, 1857

The Plum Garden at Kameido is one of Utagawa Hiroshige’s most recognizable designs. Its fame was amplified because it was copied by Vincent van Gogh in 1887. The composition, with the extreme close-up of the tree, was very original at the time. The unexpected colors combined with the composition create an effect of delightful surprise, laced with a tiny pinch of sinister premonition. This work, created in the mid-19th century, is part of Hiroshige’s famous series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

2. Utagawa Kunisada, Yosooi of the Matsubaya House With Attendants Wakana and Tomeki, ca 1831

Just look at the opulence of the clothing in this print. This is a true celebration of beauty, fashion, hedonism, and enjoying life to the fullest. And with a good reason–Utagawa Kunisada was extremely successful during his life. His fame and reputation far exceeded those of Hiroshige (above), Hokusai or Kuniyoshi (sample work of both below). Interestingly, European collectors considered him an inferior artist, as his works come from the late stage of the ukiyo-e art period. He was considered decadent, and his work was only reevaluated in the 1990s.

3. Kitagawa Utamaro, Three Beauties of the Present Day, ca 1792–1793

This is an example of bijin ōkubi-e or “large-headed pictures of beautiful women,” which isn’t to say they had large heads, but that they were pictured in a close-up, showing only the upper torso and head, rather than the full figure. Kitagawa Utamaro’s work reached Europe in the 19th century and greatly influenced the Impressionists, among others. His use of partial views was of particular interest and became a much-imitated feature.

4. Katsushika Hokusai, Kinoe no Komatsu, 1814

Yes, this work is also by the Hokusai, him of the famous Wave. You can see how he adapted his style depending on the topic. This print was part of Kinoe no Komatsu (Pining for Love), a three-volume book of shunga (erotic art) printed in 1814. Interestingly the book is not only a series of erotic prints–it also includes a plot, telling the story of the sexual adventures of Hanada Umenosuke.

5. Tsuchiya Koitsu, Snow at Miyajima, 1937

Crafted by the renowned Japanese printmaker Tsuchiya Koitsu, this artwork transports viewers to a tranquil landscape blanketed in snow. Against the backdrop of the island’s iconic torii gate, the snow-covered trees and rooftops create a picturesque scene of serenity and tranquility. You can already appreciate that Japanese woodblock prints explore many different themes and go beyond just the pictures of the floating world, and we’re only getting started.

6. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, Naosuke Gombei Ripping off a Face, 1867

Now things are getting interesting. Created in the late 19th century during Japan’s Meiji period, this print depicts a gruesome scene of violence and horror. With this print, we are moving from the ukiyo-e typical subject matter, such as female beauties, kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers, scenes from history, and folk tales, towards muzan-e (無残絵), also known as the “bloody prints.” In the center of the composition, Naosuke Gombei, a notorious criminal, mercilessly tears off the face of his victim, his expression twisted with rage and malevolence. Through this chilling portrayal, Yoshitoshi confronts the darker aspects of human nature and the brutality that lurks beneath the surface of society.

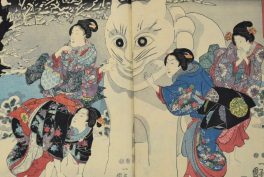

7. Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, ca 1844

This print is another example of a topic typical for the ukiyo-e: the historical and mythical scenes. We can see here Princess Takiyasha with a scroll, summoning a giant skeleton to frighten Ōya no Mitsukuni. Princess Takiyasha was a historical figure, the daughter of the provincial warlord, who tried to set up an “Eastern Court” in competition with the emperor in what now is Kyoto. Takiyasha’s father was defeated and decapitated, and Ōya no Mitsukuni was an imperial official who came to the family’s residence looking for the remaining conspirators.

8. Utagawa Kunisada, Woman in Winter Garden, 1830-1840

After the gory and the scary, let’s go back to the more pleasant themes in the ukiyo-e: beauty. Just look at this spectacular winter kimono; it is an artwork in and of itself. While very thick to keep its wearer warm, the kimono’s pattern makes it look light and graceful, breaking the huge form into smaller pieces for us to admire.

9. Utagawa Hiroshige, New Year’s Eve Foxfires at the Changing Tree, Ōji, ca 1857

As we’re nearing the end of our journey, let’s go back to calmer views after all the excitement of various types of ukiyo-e. Here, a procession of foxes approaches the viewer and all hold fire to set numerous kitsunebi (foxfires). This rite is a celebration of the Inari cult in eastern Japan, which focuses on the god of the rice fields, for whom foxes are the messengers.

10. Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, ca 1830-1832

Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa stands as one of the most iconic and instantly recognizable images in the history of art, so this list could not omit it, even if you know it too well. Created as part of his series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji in the early 19th century, this woodblock print captures the raw power and beauty of nature. Towering above a tiny fishing boat, the majestic cresting wave looms with breathtaking force, its frothy spray frozen in time against the backdrop of Mount Fuji’s serene silhouette.

As you can see, the art of Japanese woodblock printing goes well beyond Hokusai’s Wave. It is an endless source of inspiration and opportunities to consider various aspects of beauty and art.