Summary

- Bill Traylor is one of the 20th-century’s most important artists and one of the greatest artists the mainstream art world has never heard of.

- As a memory painter, Clementine Hunter painted scenes on canvas, wood panels, jugs, window shades, and cast iron skillets while living on Melrose Plantation.

- Nellie Mae Rowe created dolls, sculptures, drawings, paintings, and even a bubblegum sculpture, creating her own magical “playhouse” in the front yard of her Georgia home.

- A gravedigger, a visual artist, and one of the South’s most legendary blues musicians, James “Son Ford” Thomas incorporated human teeth into his one-of-a-kind busts.

- Thornton Dial’s work, which tackles racial oppression and injustice, is featured in the private and public collections of Jane Fonda and notable museums.

- Gee’s Bend, Alabama, with a population of less than 1,000, has somehow produced “the most miraculous works of modern art” with its world-famous quiltmakers.

- Mary T. Smith used house paint and tin to create a highly public autobiographical environment, which catapulted her to one of the most in-demand self-taught artists of the South.

- With limestone and chisels fashioned by railroad spikes, William Edmondson began carving biblical figures after a vision came to him in his 60s.

- Sister Gertrude Morgan wore all white. She played loud music and sang loudly. She also spread the gospel through her vivid and colorful works of art.

- Elijah Pierce hopped on a train to Ohio to start a life as a barber. His art career began with a wood carving for his wife and turned into countless wood carvings of animals and biblical scenes.

- Described as spooky and dark, Bessie Harvey struggled throughout her life, turning that pain into the perseverance to make found object sculptures.

- Sam Doyle, one of the few artists who showed promise as a child, didn’t start painting full-time until his retirement, during which he would record the history of his community with paint and sheet metal.

- After being severely injured when a slab of marble crushed his legs, Mose Tolliver took up painting to fight boredom and often would paint ten vibrant and wildly creative works of art a day.

For almost one hundred years, the United States has recognized African Americans in February to coincide with the birth of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. In that time, countless prominent Black Americans have celebrated the struggle and the strength and courage of Black people living in the United States who continue to persevere despite the racial tensions and divide that continue to affect the day-to-day lives of millions of people.

There is no better place and group of people in the art world to recognize than that of Black folk artists in the American South. Today and every day, these creators deserve to be celebrated and recognized as great American Black folk artists and some of the best artists this country has ever seen.

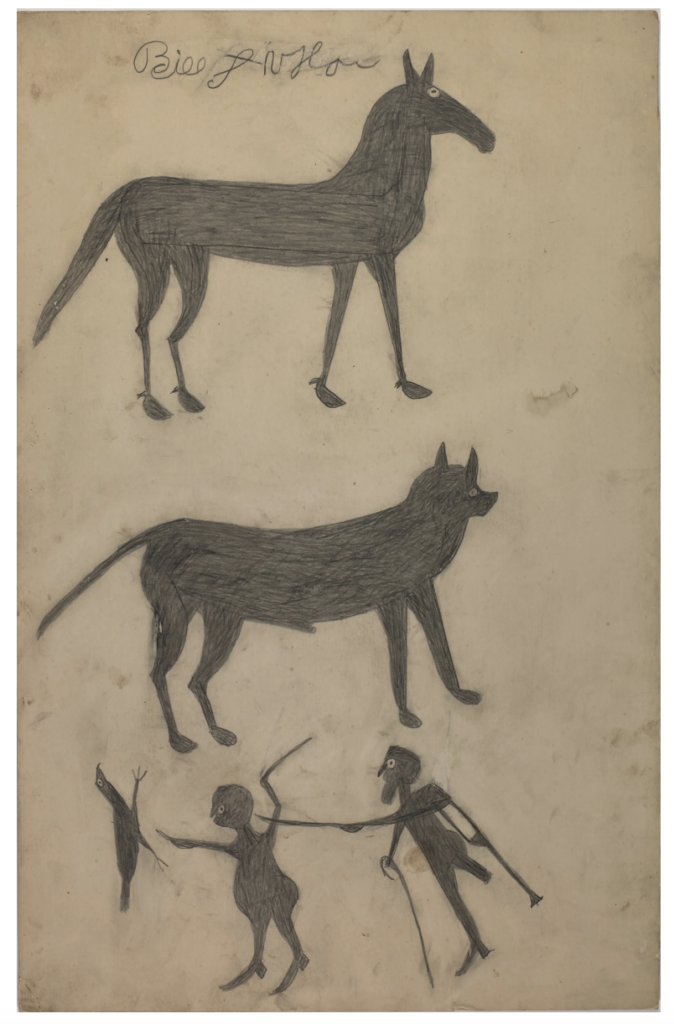

1. Bill Traylor

Bill Traylor, Untitled (Radio), c. 1940–1942, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Bill Traylor (1853–1949) is considered one of the greatest American artists of the 20th century. Entirely self-taught, Traylor was born into slavery in 1854 in Benton, Alabama, and spent most of his life working as a sharecropper. In the late 1930s, he wound up unhoused and living on the streets of Montgomery, Alabama, drawing scenes of a bustling town on the backs of found pieces of cardboard.

His originality, storytelling, and emotion in each of the nearly 1,500 works he created in ten years will make the hair on your arm stand up. While there was a brief chance in the last years of his life that NYC’s Museum of Modern Art would acquire his works, ultimately, the museum’s then-director, Alfred Barr, known for his love of “primitive” artwork, passed. For decades, Traylor’s work sat in private collections, whereas today, his work regularly sells for tens of thousands of dollars. One previously owned by Steven Spielberg fetched half a million dollars.

There are not many artists who were able to record life quite like Bill Traylor. He saw the emancipation of enslaved people, Jim Crow laws and Reconstruction, World Wars, the Great Migration, and a segregated Alabama that left him living on the streets of Montgomery into his 80s. Animals, men, women, fights, construction, drinking—Traylor painted a lot, he had seen a lot, and his works, which can be seen in countless museums across the country, leave behind a vibrant, complicated, and changing time seen through the eyes of many, but recorded brilliantly by one man.

2. Clementine Hunter

Clementine Hunter, Masked Face, 1962, oil on panel, New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Clementine Hunter (1886/1887–1988) was a self-taught folk artist from the Cane River region of Louisiana who lived and worked on Melrose Plantation. Clementine (pronounced Clem-en-teen) is described as a memory painter who documented Black Southern life. Having had no formal art training, after years of working at Melrose Plantation, a colony for artists and writers, she picked up a paintbrush and started painting on anything she could get her hands on—windows, cast iron pans, jugs, wood, cardboard—anything.

After years of painting, and with the help of guests of Melrose Plantation, Hunter started selling her work. A sign would hang outside her home that said, “25 cents to loo,” and her paintings were often displayed in the local drugstore where they were sold for a dollar. Her works are mostly narrative, depicting important life events in her beautifully colorful palette-like funerals, baptisms, and weddings, with some scenes of plantation life such as picking cotton or pecans.

Hunter’s work is in the American Folk Art Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the New Orleans Museum of Art, and a handful of U.S. museums. She has been described as “the most celebrated of all Southern contemporary painters.”

READ MORE: Five Black Female Artists Everyone Should Know

3. Nellie Mae Rowe

Nellie Mae Rowe, Peace and Happiness, 1979, crayon and marker on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

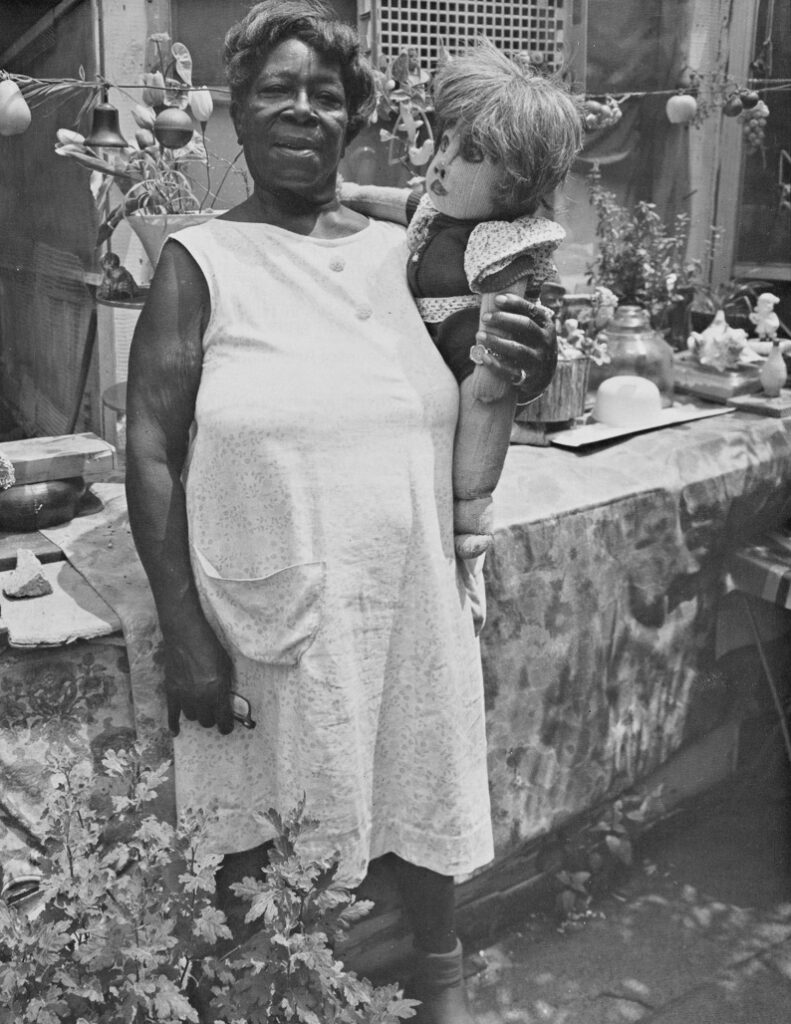

Nellie Mae Rowe (1900–1982) may be best known today for her colorful works on paper, but it was the home installations and sculptural environments that first garnered her attention and thrust her into the national spotlight—along with her collages, altered photographs, and hand-sewn dolls. Born to once-enslaved parents, Nellie Mae Rowe was a laborer as a child, married as a teen, and left widowed twice.

Despite a young life of hard work and pain, her works are extremely joyful, colorful, and full of life. Her home was transformed into a magical wonderland of art called “playhouse.” It was a place that celebrated her friends, neighbors, and loved ones, full of artworks created with found objects. Some even included chewing gum she kneaded into creature shapes and chilled in the freezer. A visitor once recalled, “Everyone from architects to the local deliveryman stopped and stared because it was an astounding creation.”

Nellie Mae Rowe with Little Nellie. Photo by J. Wieland (1978), Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

One of the first self-taught Black women celebrated for her artwork, she saw considerable nationwide attention and some financial success at the end of her life. In 1989, the Guerilla Girls recognized Nellie Mae Rowe among the ranks of Frida Kahlo, Edmonia Lewis, and Georgia O’Keeffe. Her work is in major museums across the country, with the High Museum of Art in Atlanta housing over one hundred of her sculptures, drawings, and paintings.

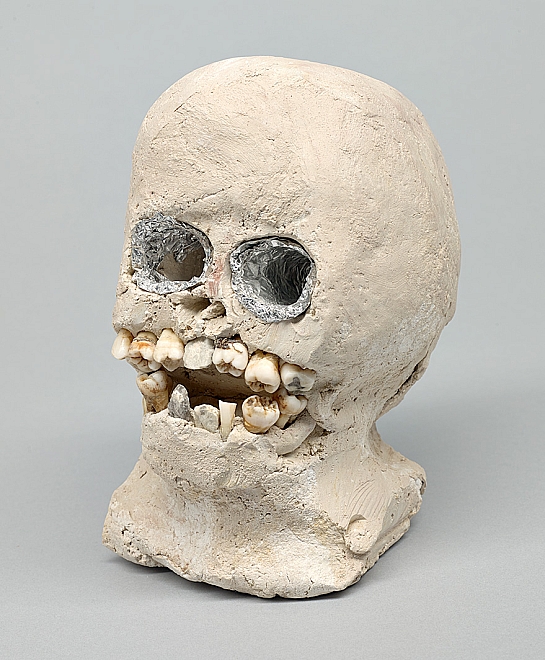

4. James “Son Ford” Thomas

James “Son Ford” Thomas, Skull, 1988, unfired clay, human teeth, rocks, aluminum foil, Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

James “Son Ford” Thomas (1926–1993) was an American gravedigger, blues musician, and self-taught sculptor. Thomas taught himself everything. He learned to play guitar and write music by listening to the blues on the radio while working in the fields. While working as a gravedigger, he taught himself how to make unfired clay-sculpted images of skulls, digging the clay himself out of the Yazoo River and featuring human teeth.

The skulls and unfired clay reflected his life as a gravedigger and his personal philosophy that “we all end up in the clay. ” The ugliness of each piece and the explicit nature of death in his work reminds the viewer of mortality and makes the audience reflect more deeply about life. On weekends, Thomas could be found playing music at numerous blues festivals in Mississippi or private events.

If you refer to James Thomas, no one would likely know who you are talking about. But if you asked about “Son Ford,” a nickname he received as a kid because he would make Ford tractors out of clay in school, everyone in the South would know who you are talking about.

5. Thornton Dial

Thornton Dial, The End of November: The Birds That Didn’t Learn How to Fly, 2007, quilt, wire, fabric, and enamel on wood, Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

Thornton Dial (1928–2016) has some of the most impressive and stunning oeuvres of any artist you’ll meet. Fortunately, he lived to see his work enter the collections of some of the most prominent museums in the United States and become a part of the mainstream art world in unprecedented ways, defying what it meant to be a Black folk artist.

What he does can be discussed as art, just art, no surplus notions of outsiderness required…And not just that, but some of the most assured, delightful and powerful art around.

Time Magazine

Thornton Dial’s work reflects his life, tackling issues of racial oppression and injustices he experienced his entire life, living through Jim Crow segregation and the Civil Rights Movement. Part of the inspiration for his monumental large-scale works, which include complex assemblages of found materials, came from a drive to Bessemer, Alabama, where his family relocated when he was twelve. He noticed the large-scale works of metal and art in people’s front yards.

Dial worked as a metalworker at a plant that made railroad cars until 1981 when the doors closed. A few years later, as Dial continued to work, he was introduced to Atlanta collector and art historian William Arnett. The rest is history, as his work was presented at the Whitney Biennial, in the personal collection of Jane Fonda, and in 2014, when ten of his bold and captivating works of art were acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

READ MORE: Black Contemporary Artists Everyone Should Know

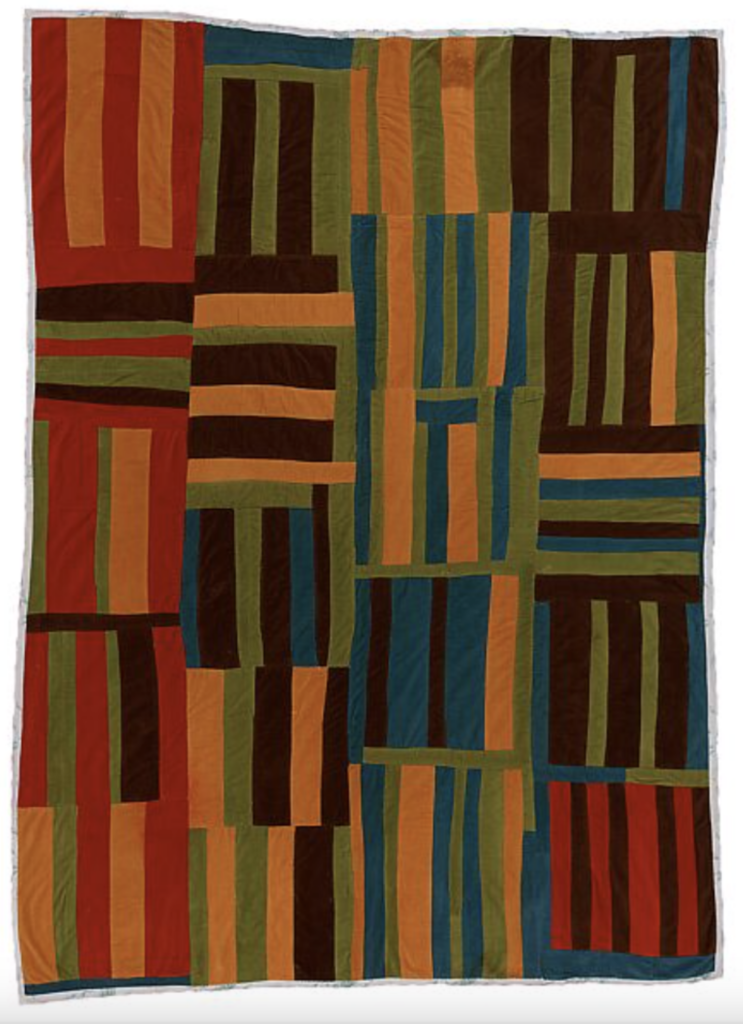

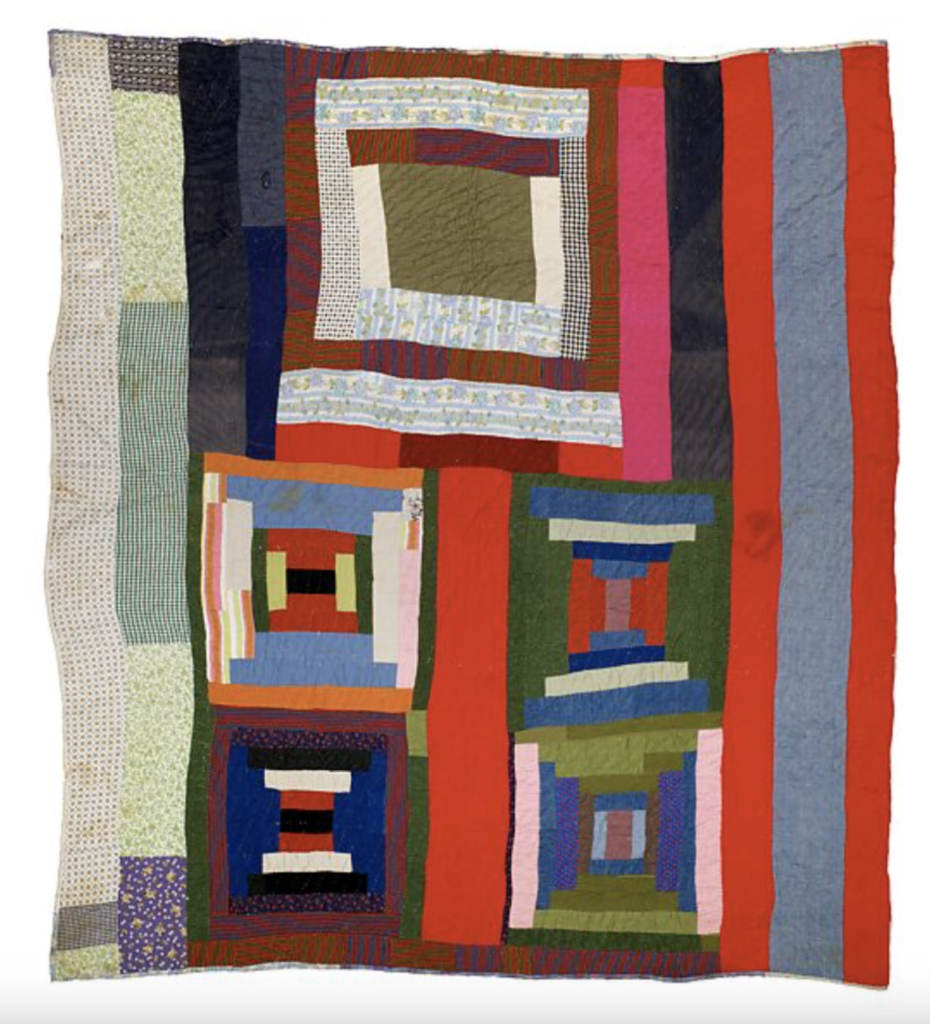

6. Gee’s Bend Quiltmakers

There is no quilt like a Gee’s Bend quilt. Considered some of “the most miraculous works of modern art America has ever produced,” these quilts stand alone in their style, color, and unique patchwork, coming from a small but tight-knit community of African-American women in the South. The quilts shown here were donated to The Met Museum in 2015 by William Arnett, an American art collector of art in the South and the founder of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, an organization dedicated to the preservation and documentation of African American art from the Deep South.

Familiar names in the Gee’s Bend Quilting community, like Lucy T. Pettway, Annie Bendolph, Loretta Pettway, and Willie “Ma Willie” Abrams picked up these techniques and traditions from a long line of quilters who have lived in Gee’s Bend, Alabama, since the 19th century. True folk artists, the Gee’s Bend quilters often would quilt together, building an even stronger sense of community for a group of women who had already been through so much together.

7. Mary T. Smith

Gee’s Bend women have made quilts for over one hundred years to keep themselves and their children warm in unheated homes that lacked running water, telephones, and even electricity. Things have improved, and during that time, these quilters developed a distinctive style, thrilling improvised patterns, and geometric simplicity.

![black folk artists: Mary T. Smith, Jeuus No T [“Jesus Know”], 1987, paint on wood, Souls Grown Deep Foundation.](https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/SG201843352.jpg)

Mary T. Smith, Jeuus No T [“Jesus Know”], 1987, paint on wood, Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

Mary T. Smith (1904–1995) is another artist heavily promoted by collector William Arnett, who championed Southern self-taught artists like Nellie Mae Rowe and Thornton Dial, among others. Born in Mississippi in 1905, Smith used house paint on wood or tin to create colorful and expressive works of figures, some biblical, sometimes with abstracted text with lots of dots and dashes.

Taking up painting in her seventies, after turning her home and property into a “highly public form of spiritual autobiography,” or as some might term, a beautifully decorated art environment, collectors eventually took notice. Smith soon couldn’t keep up with the demand.

Her work, once likened to that of Jean Michel-Basquiat, can be seen in many private collections and galleries across the United States and Europe. In 2022, it was exhibited at the National Gallery of Art’s “Called To Create: Black Artists of the American South” exhibit and is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s permanent collection.

8. William Edmondson

William Edmondson, Crucifixion, c. 1932–1937, limestone, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

William Edmondson (1874–1951), born on the Compton Plantation in Davidson County, Tennessee, was the first African-American folk art sculptor to be given a one-person show exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City (1937).

He never considered himself much of an artist when he began carving leftover limestone with chisels fashioned from railroad spikes. He was a laborer and began carving gravestones and biblical figures after a vision he had in 1932 in which he said, “Jesus has planted the seed of carving in me.”

Like many self-taught folk artists, it wasn’t until he was sixty years old that his work started getting noticed, although he never made any large sums of money for his work, which ranged in height from one to three feet.

William Edmondson, Martha and Mary, c. 1931–1937, both before and after conservation by Linda Nieuwenhuizen. Photo by Linda Nieuwenhuizen, courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York City, New York, USA via artnet.com.

In 2019, art collector John Foster drove by a home in St. Louis and noticed a limestone sculpture on the front porch of a home. He returned a few days later with a hunch that this could be a piece by William Edmondson. After discussions with the owners, completely unaware of the “holy grail” they had sitting on their porch, the piece was confirmed to be created by Edmondson, titled “Martha and Mary,” sometime in the early 1930s.

The piece was later bought by contemporary artist KAWS and donated to the American Folk Art Museum, where he serves on the board.

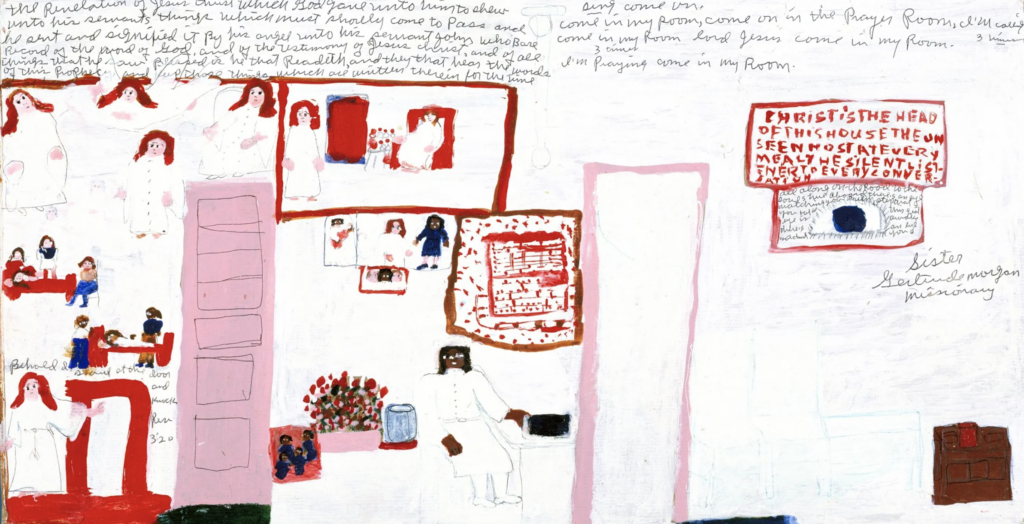

9. Sister Gertrude Morgan

Sister Gertrude Morgan, Come in My Room, Come On in the Prayer Room, c. 1970, tempera, acrylic, ballpoint pen, and pencil on paperboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Sister Gertrude Morgan (1900–1980) was a self-taught African-American artist, musician, poet, and preacher. Born in Alabama, she relocated to New Orleans in 1939 to begin missionary work, ultimately opening a shelter for runaway children and teenagers needing food and a home. Her preaching consisted of singing and dancing, and in 1956, she started wearing only white. Around that time and for the next ten years, Morgan is said to have been instructed by God to start drawing pictures of the new world to come.

Her works are interpretations of the Book of Revelation and illustrate her life dedicated to religion and her visions. With human characters created using very simplistic forms and no depth or perspective, Morgan used acrylics, tempera, ballpoint pens, watercolors, crayons, colored and lead pencils, and felt tip markers on anything she could get her hands on—including but not limited to paper, toilet paper rolls, album covers, scrap wood, and lamp shades.

This signing of her works with names like “Black Angel,” “Lamb Bride,” or “Everlasting Gospel Revelation Preacher,” among others, led her to be described anywhere from a naive or visionary artist to a folk or outsider.

READ MORE: Black Feminist Photographers Fighting for Social Inclusion

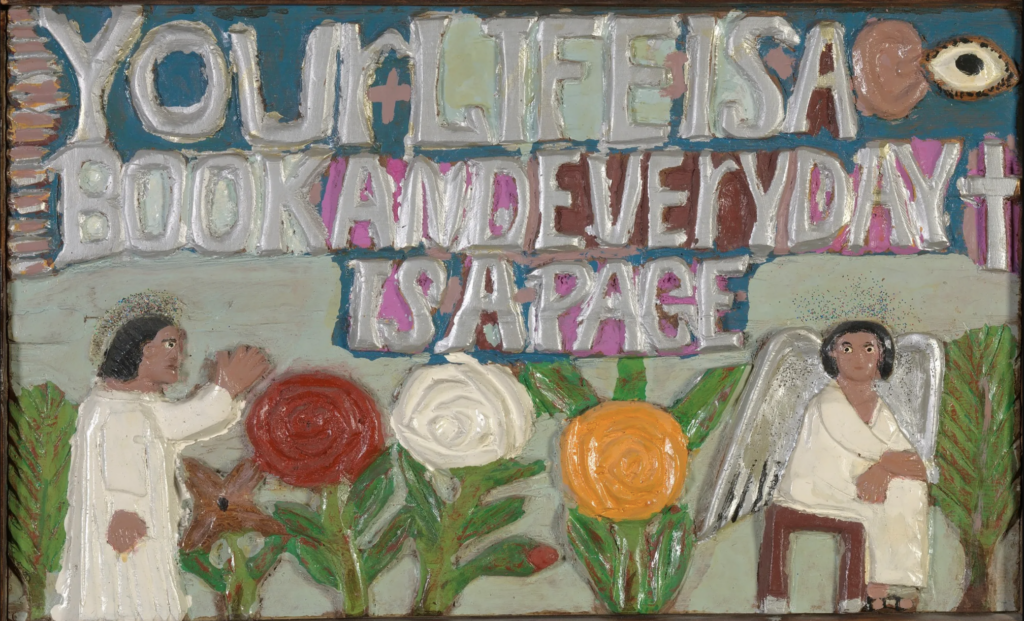

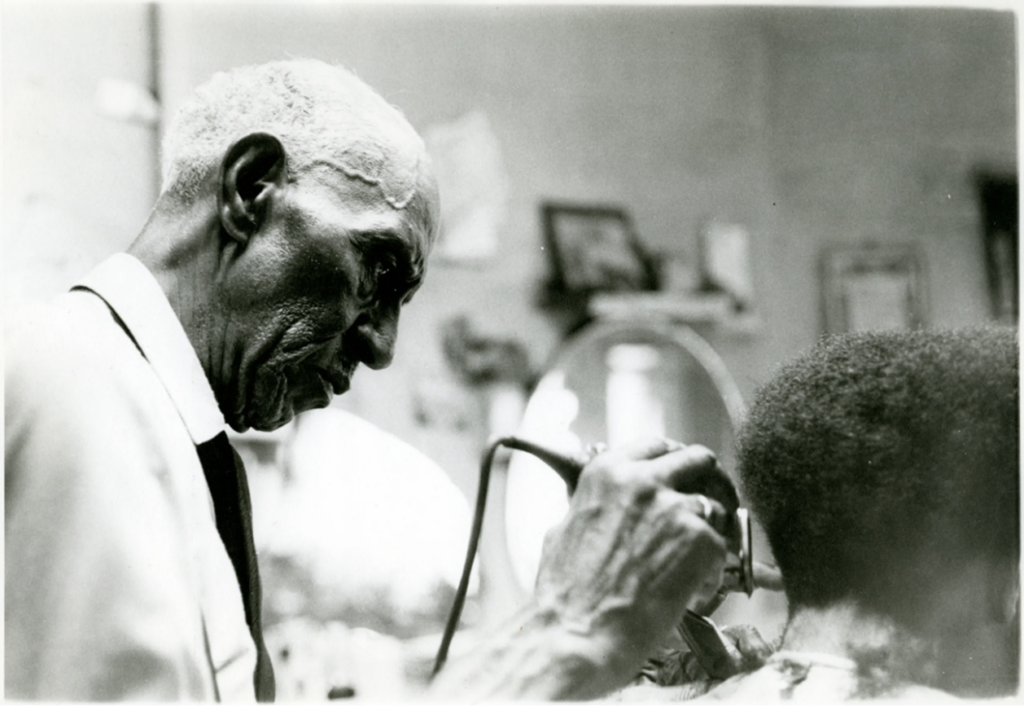

10. Elijah Pierce

Elijah Pierce, Your Life Is a Book and Every Day Is a Page, 1973, carved and painted wood with glitter, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Elijah Pierce (1892–1984) was a self-taught wood carver who began carving at a young age using a pocket knife. He didn’t want to work on his father’s farm in Mississippi; instead, he wandered around in the woods, incising names into tree trunks and carving little animals.

After leaving home, traveling by freight train, and winding up in Columbus, Ohio, Pierce opened a barbershop and lived a quiet life with his wife. In the late 1920s, as a gift for his wife, he carved a little elephant out of wood and changed the course of his life. She loved his gift so much that Pierce carved an entire zoo and kept carving every spare minute he had that he wasn’t cutting hair.

Photo by Kojo Kamau, courtesy of the Archives of the Columbus Museum of Art, OH, USA, via Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA

Over time, Elijah Pierce’s subject matter turned to religious scenes from the bible, as he believed God had given him the talent to carve, and it was his mission to spread the word. It wasn’t until the 1970s that his work started gaining the art world’s attention. In 1982, the National Heritage Fellowship awarded him the National Endowment for the Arts, the United States’ highest honor in folk arts. Today, his work can be found in the permanent collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the American Folk Art Museum, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, among others.

11. Bessie Harvey

Bessie Harvey, The Poison Of The Lying Tongues, 1987, found wood, cowrie shells, plastic beads, nails, and paint, Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

Bessie Harvey (1929–1994) was an American artist best known for her sculptures constructed of found objects, primarily pieces of wood. She lived in intense poverty. Towards the end of the Great Depression, she started making art as a way to deal with life’s struggles and to survive. What began as small twigs that appeared doll-like evolved into rather complex works of art that included many materials, including found objects and paint. Harvey created a wide range of characters that she believed God gave her the power to see.

Finally, in the 1980s and 1990s, her work was noticed. As it was more primitive than that of most self-taught artists, it was often regarded as mythical or related to some dark arts or spooky religions. Her vision and determination never waivered, as the pain and struggle helped get her to where she was, and this was the motivation and perseverance that kept her going.

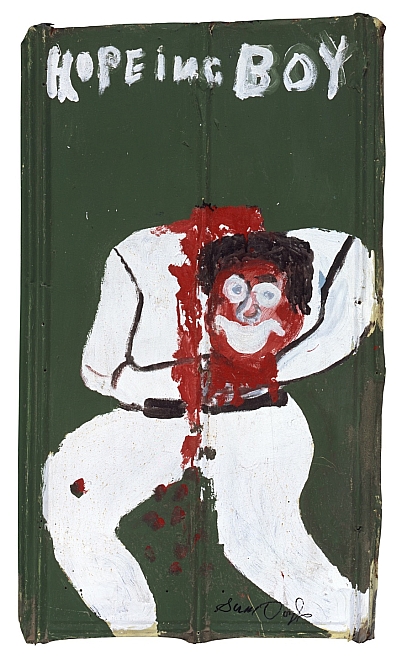

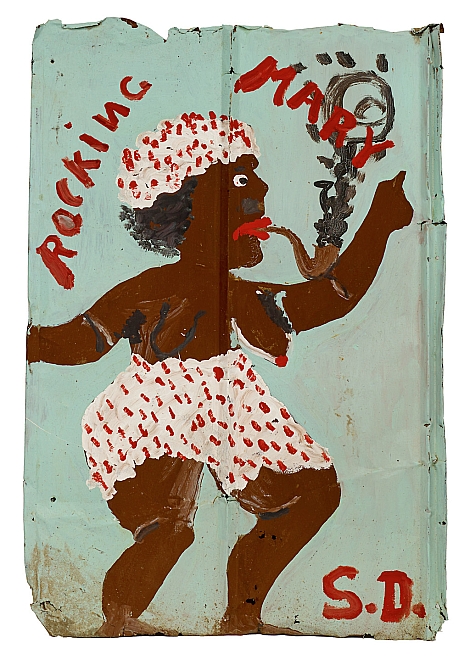

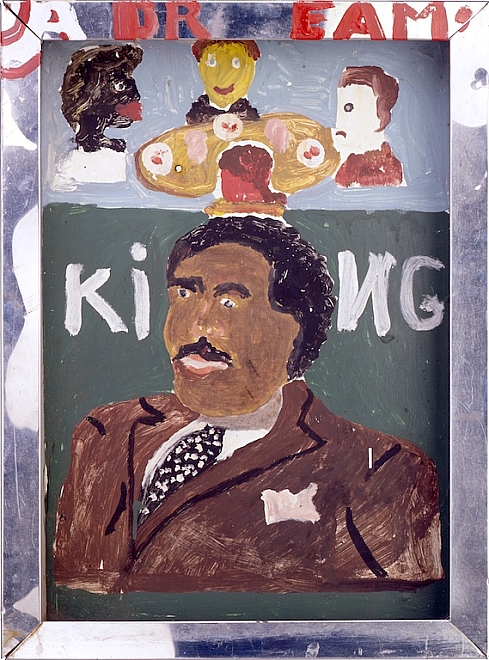

12. Sam Doyle

Sam Doyle (1906–1985) was an African-American artist from Saint Helena Island, South Carolina. His colorful paintings on sheet metal and wood recorded the history and people of his community. Unlike many folk artists on this list, Doyle’s teachers noticed his artistic ability when he was young and encouraged him to pursue his artistic practice.

Unfortunately, it would be another three decades after dropping out of school in the ninth grade and working odd jobs before Doyle started painting again. Using found and discarded materials, notably metal roofing and housepaint, he created a unique art style showcasing the strengths and weaknesses of his fellow residents, as well as African American legends and heroes like Jackie Robinson and Martin Luther King Jr.

In the late 1960s, Sam Doyle retired from his day job and started painting daily. In 1982, his work was included in the “Black Folk Art in America” 1982 exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art.

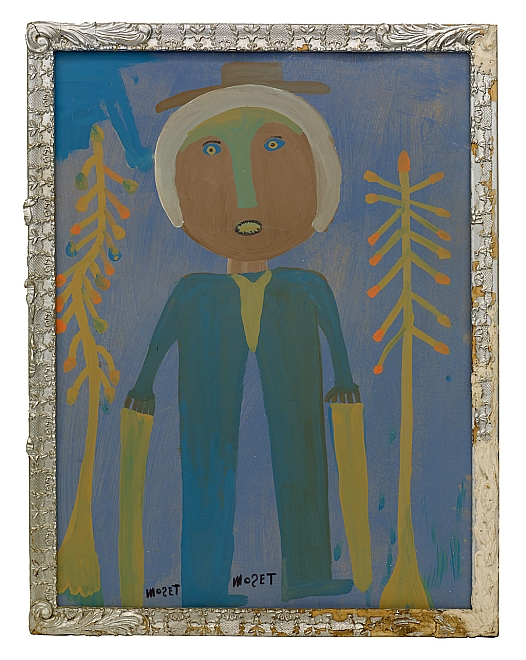

13. Mose Tolliver

Moe Tolliver, Self-Portrait Of Me With Crutches, 1983, housepaint and marker on poster board with painted frame, Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

Mose Tolliver (1918/1920–2006) dropped out of school after the third grade due to a lack of interest. He was born around 1920 and worked odd jobs most of his life in and around Montgomery, Alabama.

He started painting in the 1960s after a half-ton of marble fell off a forklift and crushed his legs to fight boredom and alleviate the pain from his injury. Tolliver claims he was painting before the injury and refused to take lessons after, luckily, because he wanted to create and work in his style. He painted in his bedroom, sometimes with the plywood or masonite on his bed, sometimes on his legs. Tolliver painted up to ten vibrant works daily, from watermelon to animals, religious works, and women. Some of his pieces are not necessarily “safe for work,” with wildly creative, or even erotic, titles like Jick Jack Suzy Satisfying her own Self.

SHRINE Gallery recreates Mose Tolliver’s bedroom at the 2018 Outsider Art Fair / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City, NY, USA, Adam Reich

New York-based SHRINE Gallery beautifully recreated Tolliver’s bedroom and work at the 2018 Outsider Art Fair. His pieces can be found in over a dozen major museums across the United States, likely hung up with his signature hand-crafted hanging device, a metal soda can ring.