Lotus Temple and the Bahá’í Faith

The Lotus Temple is renowned for its distinctive lotus shape. A prominent Bahá’í House of Worship in New Delhi, the temple embodies...

Maya M. Tola 27 January 2025

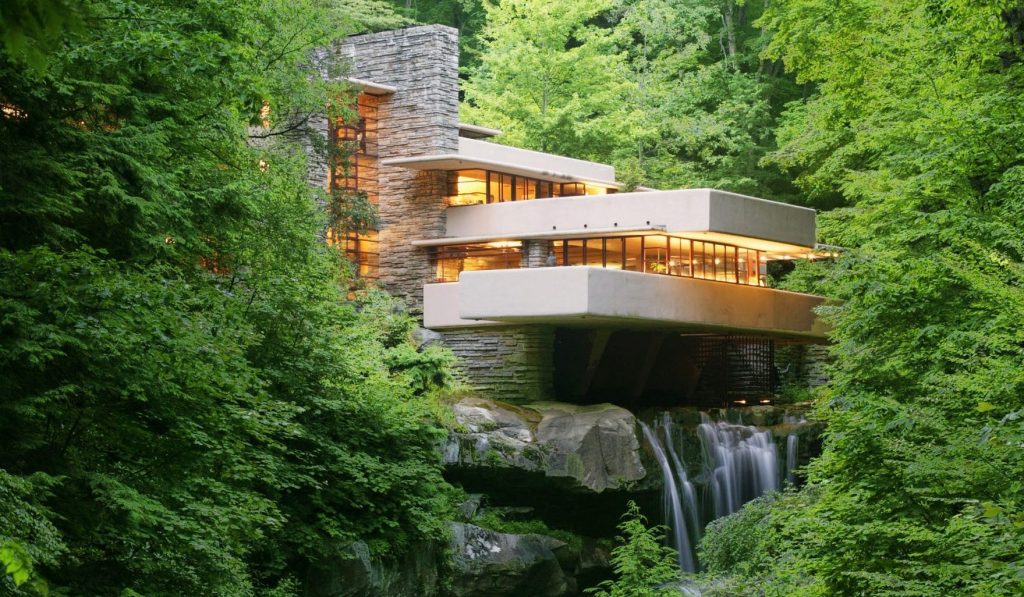

We all know the iconic realizations designed by Frank Lloyd Wright: everyone recognizes the Guggenheim Museum in New York or the famous Fallingwater Villa. But with over 1000 buildings designed, a large part of Wright’s projects have not been realized (around 600 designs!). If you ever wondered what they may have looked like, you are not alone. Angi, “the home for everything home” as they call themselves, beautifully rendered in 3D three of Wright’s designs. Their work makes it easier for us to dive in and explore what those projects may have looked like. Join us in this exploration!

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater, 1935, Mill Run, PA, USA. Keystone Edge.

Wright’s career lasted over 70 years and he was an extremely prolific architect. He was also known to be quite stubborn and not necessarily the easiest person to work with. A fact that is often forgotten is that a large part of being an architect is working with people, especially clients. Architects are not solitary geniuses creating in isolation. Their work is always a result of the collaborations between the client and the artist. This sometimes led Wright to abandon the projects, or the clients to abandon him.

On the other hand, Wright was able to work with the Taliesin Fellowship, a group of architect apprentices who effectively formed his workshop. It seems that as long as he had the last word he was fine working with people. Otherwise, he preferred to leave rather than yield to the client’s wishes he disagreed with.

Wright’s style was initially shaped by his work at Louis Sullivan’s practice, but quickly he decided to strike on his own. His signature Prairie Style quickly developed, drawing on his experiences of growing up at the farm in the constant vicinity of nature. The idea was to remain close to nature merging the houses with their environment organically.

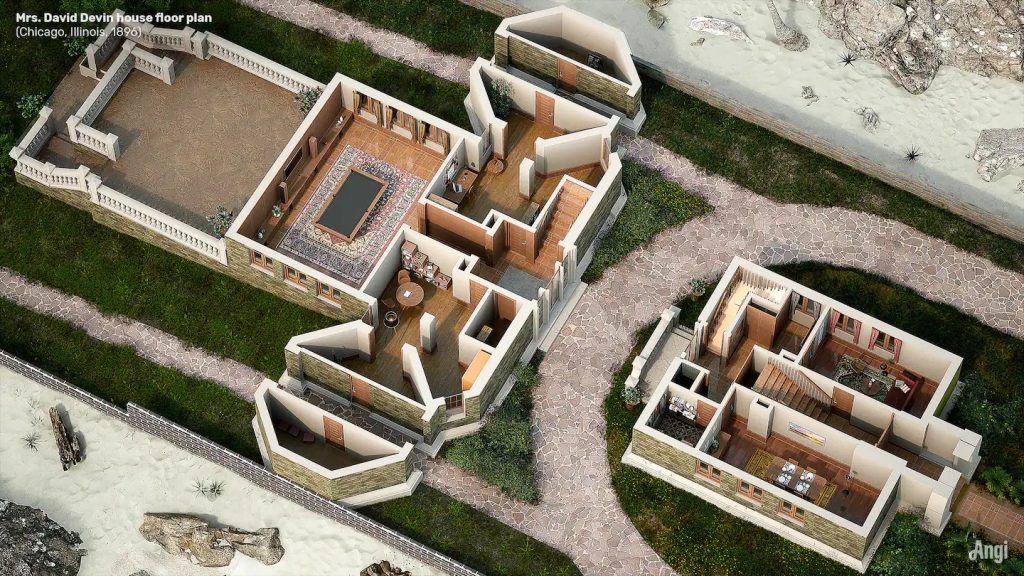

Frank Lloyd Wright, Project of Devin’s House, 1896, Chicago, IL, USA. Rendered by Angi.

This house is not designed in a style that we would easily associate with Wright’s work. This is because the client, Aline Devin, has specifically asked for something unique and special. It is an early project, but it does stand out from other designs of the time. It was never constructed, this time it seems the client decided to end the cooperation early. Today it is hard to say whether if constructed this one design may have taken Wright’s thinking in a different direction.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Project of Devin’s House, interior, 1896, Chicago, IL, USA. Rendered by Angi.

The floorplan is very interesting, as we can see that, in fact, it is not one house but two. Also, the way the space is divided is very unusual, making us ask some questions about the functionality of some of these rooms, given their atypical shapes.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Project of Lake Tahoe Lodge, 1923, Lake Tahoe, CA, USA. Rendered by Angi.

This is an interesting case since there was no client or commission here. Wright made this design for himself, possibly hoping to somehow acquire the undeveloped site on the shores of Emerald Bay. He designed the entire summer camp, including some floating cottages, and here we can see one of the more traditional ones. Though to call it both traditional and a cottage is a bit of a stretch. On the outside, it looks a bit like a fort, not a friendly cozy cottage, and then when you take a look at the floorplan you’ll notice it is more of a villa than a cottage.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Project of Lake Tahoe Lodge, interior, 1923, Chicago, IL, USA. Rendered by Angi.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Project of cottage studio for Ayn Rand, 1946, CT, USA. Rendered by Angi.

Ayn Rand and Frank Lloyd Wright corresponded for 20 years, and have certainly met several times. It is broadly accepted that Wright was the inspiration for Howard Roark in Ayn Rand’s book The Fountainhead. A young, moody, strong architect going against the current and always ahead of his times, that was probably how Rand perceived Wright. Though he didn’t seem happy with the association and reportedly said regarding Howard Roark “I deny the paternity and refuse to marry the mother.”

That did not prevent him from designing a villa with a studio for Ayn Rand. A client is a client. The house is designed over a decade after Fallingwater, but we can see the continuity of style here. The cantilevered floors and the prevalence of the horizontal lines are very clear. As well as the idea of the house organically emerging from the environment, played beautifully here through the variance in textures between the fieldstone core and the cantilevered terraces. The interior of the house also reminds us of Fallingwater, with the whole house built around a massive living room that is open to the surrounding landscape.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Project of cottage studio for Ayn Rand, 1946, CT, USA. Rendered by Angi.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!