James Ensor: What the Mask Hides

Do you know who James Ensor was? James Ensor (1860-1949) was a scandalous, rebellious, and revolutionary Belgian painter with a style that could be...

Andra Patricia Ritisan 11 April 2024

The purpose of art for a group of avant-garde individuals at the turn of the 20th century was no longer the realistic rendition of the natural world, but the subjective interpretation of what they saw and felt. Revolting against the style of naturalism that had dominated European art for centuries, the Expressionist movement transformed art into a means of communicating the inner worlds of artists.

Often characterized by the distortion of forms, drastic use of colors, and idiosyncratic views, Expressionism injected emotionality and spirituality into art in an unprecedented way. Here are 5 expressionist artists you should know.

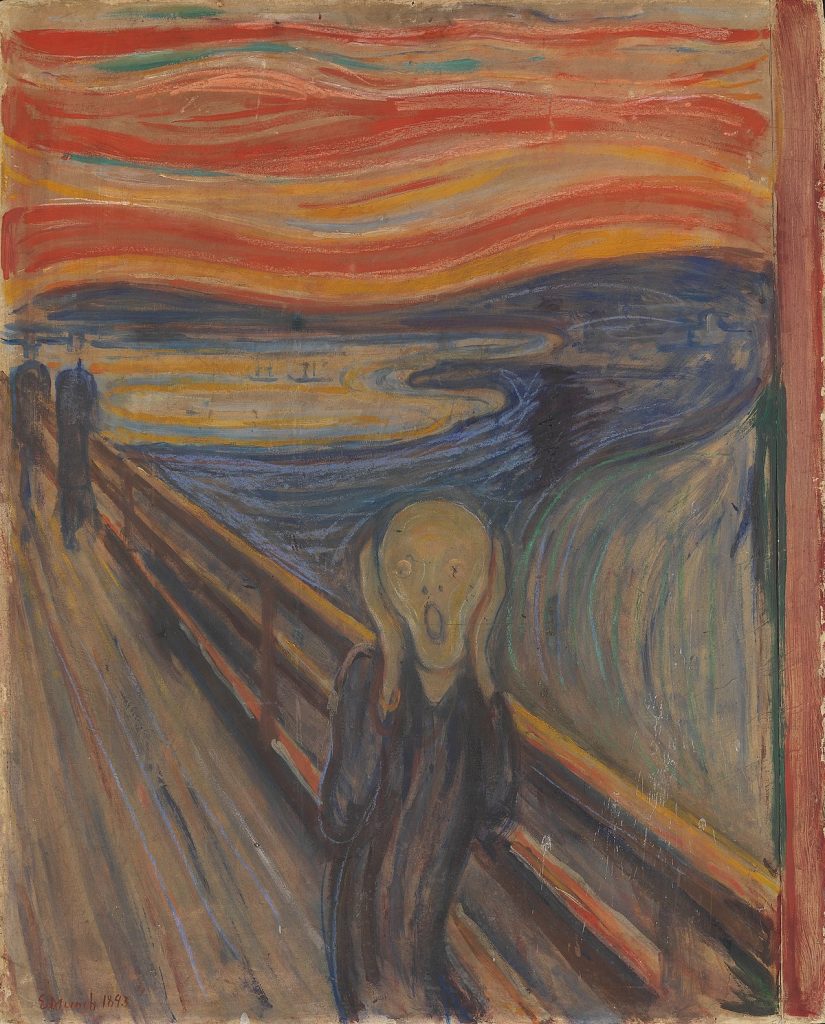

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway.

For many, the Expressionist movement is necessarily associated with The Scream, the 1893 painting created by the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch. Just as the painting is known for its deep reflection on the mental condition, Munch’s life was characterized by countless spiritual encounters with anguish, dread, and even death, which helped define his idiosyncratic artistic style.

Born in 1863 to a Norwegian middle-class family, Munch experienced a traumatic childhood that had a lasting impact on his works. His mother died in 1868, followed by his eldest sister’s death in 1877, both of tuberculosis. His father, Christian, a fanatic devotee, raised Munch and his siblings, though he constantly suffered from mental disorder. “Illness, insanity, and death” haunted Munch since he was young.

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway. Detail.

Entrapped by anxiety and distress after his father’s sudden death in 1889, Munch painted the first version of The Scream in 1893 — a painting that testified his belief that painting should be “the study of the soul.” The background of The Scream is dominated by the swirling stripes of glaring orange and a curved, blue shoreline. The painting reaches the climax in the front — a man with his body in a whirling shape, a pair of staring eyes, an ovoid mouth, and distorted hands holding his head. His helpless gestures and the overall blazing application of colors express the man’s extreme frustration in a powerful and almost suffocating way.

Munch was directly addressing the essential issue of existence or, as he put it, attempting “to explain life.”

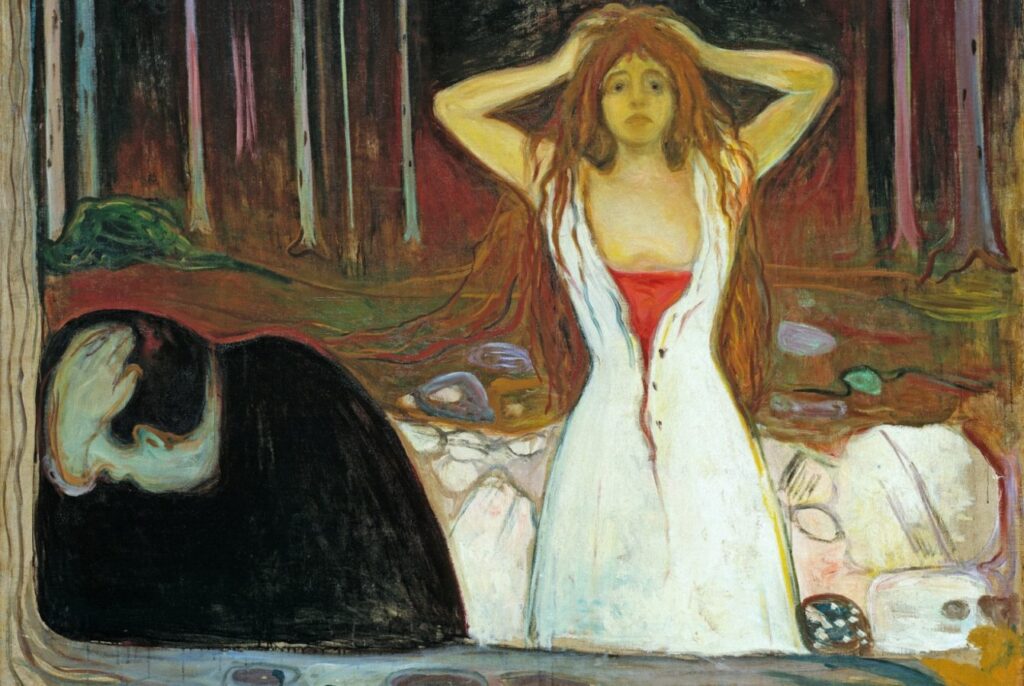

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Edvard Munch, Ashes, 1894–95, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway.

In the same year, Munch started creating a series of paintings called The Frieze of Life — A Poem about Life, Love and Death. In it, he contemplated upon love, sexuality, anguish, life, and death, which often relate to his personal experiences. The painting Ashes, for example, is the story of a desperate couple, but is also about his own distressful romantic experience.

Wassily Wassilyevich Kandinsky was a Russian expressionist and the pioneer of Western abstractionism. Born in 1866, Kandinsky grew up in Odesa and later became a successful law student, until he decided to become an artist at age 30. Influenced by the impressionistic touch of Monet’s Haystacks in an exhibition, Kandinsky began a pointillist attempt to express subjective feelings–an inclination that led to his later abstractionist experiments.

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Wassily Kandinsky, The Blue Rider, 1903, Foundation E. G. Bührle Collection, Zürich, Switzerland.

In 1910, Kandinsky founded an expressionist group named the Blue Rider, or Der Blaue Reiter, with several other artists. He also published the treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art, and articulated the principle of “revealing associative properties of color, line and composition.” His art theory is exemplified by Improvisation 28 (second version), an oil painting created in 1912.

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Wassily Kandinsky, Improvisation 28 (second version), 1912, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, NY, USA.

As the title suggests, Kandinsky’s work was intended to be a piece of musical composition, only that it employed artistic forms instead of musical notes. As he explained, “Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings.” The artist’s role is to play the music and “cause vibrations in the soul.”

The message is not the representation of forms, but the appreciation of colors and lines for their own sake. The crisscrossing black lines create the impression of a combination of exhilarating musical notes, highlighting the painting’s musicality.

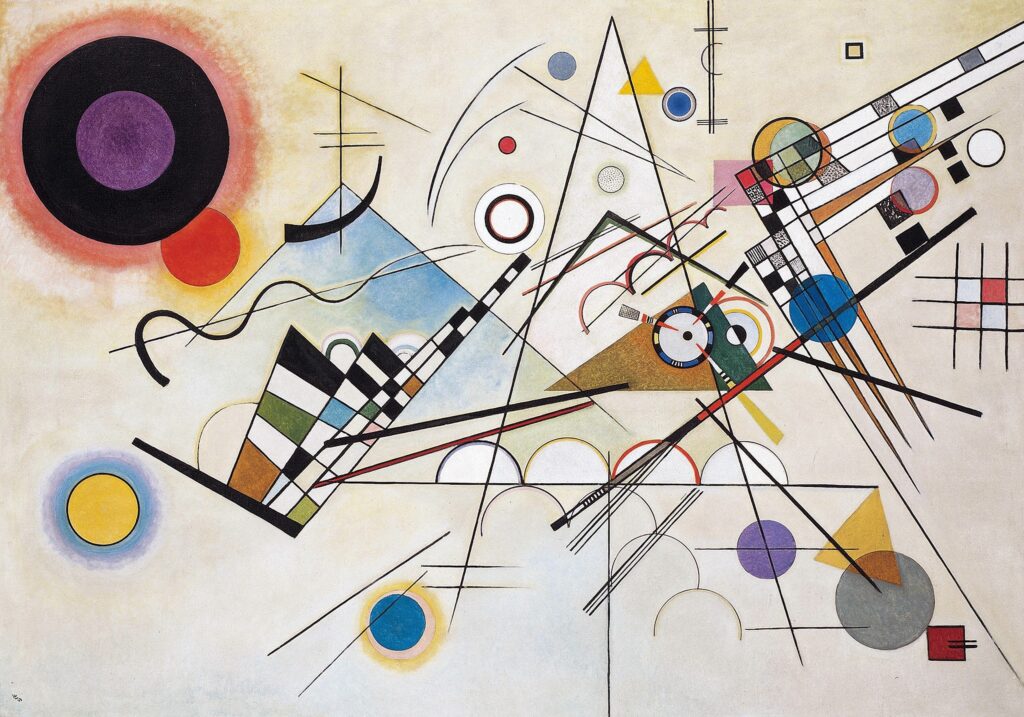

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VIII, 1923, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, NY, USA.

In 1926, he began exploring the emotional effects of abstract elements. In his 1923 painting Composition VIII, a work influenced by Russian Suprematism and Constructivism, Kandinsky experimented with the overlapping forms of trapezoids and triangles. The strict contours of flat forms are invigorated by an alternating palette, evoking dynamism and impulsion. “Form itself, even if completely abstract … has its own inner sound,” he wrote. The abstraction of forms ultimately serves the creation of spiritual harmony.

Among the modern Expressionist movement were the Fauves, or “wild beasts,” a group of radical artists known for their strong use of colors and bold brushwork. As one of the pioneers of Fauvism, the French artist Henri Matisse transformed the short-lived Fauvist movement into an enduring source of inspiration for twentieth-century artists.

Born in 1869, he grew up in Bohain-en-Vermandois, a town in Northern France, and at age 21 became determined to study art in Paris.

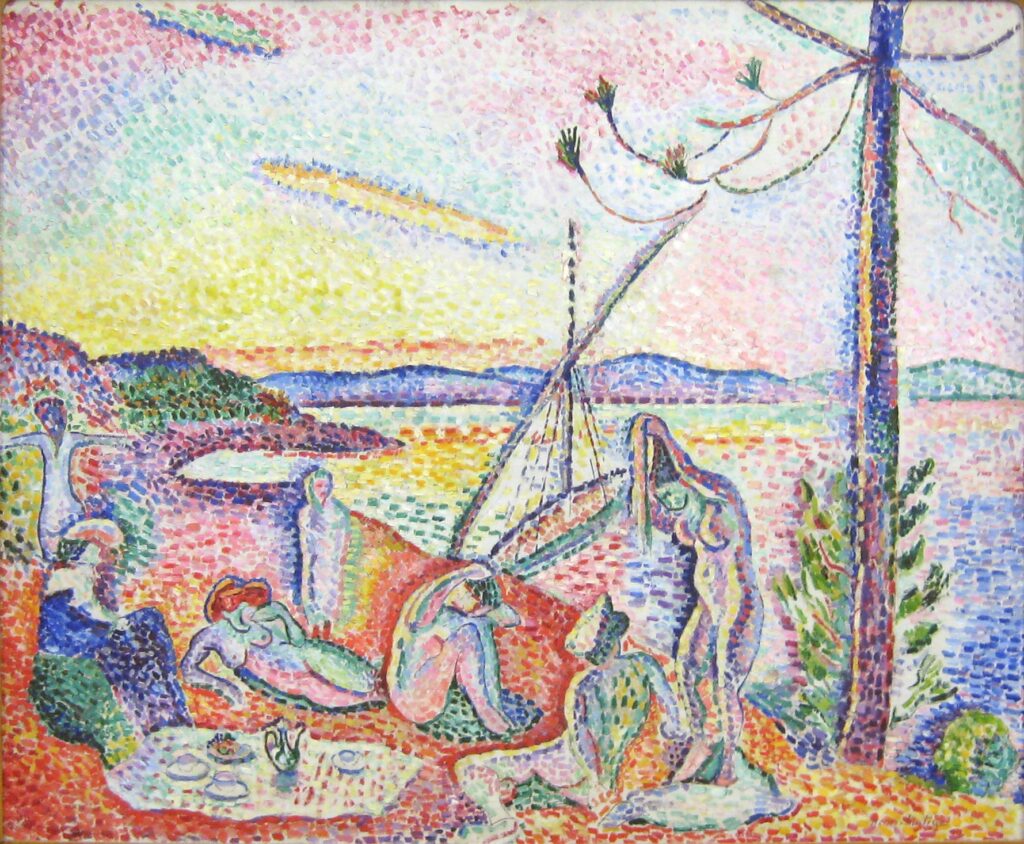

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Henri Matisse, Luxe, Calme et Volupté, 1904, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Matisse’s art journey, however, did not begin as an avant-gardist, but with training in the French academic manner. His break with the academic style came in 1904, when he spent the summer with his Neo-Impressionist friends in the small fishing village of Saint Tropez.

Inspired by the bright sunlight in Southern France, he strove to create vibrant optical effects on the canvas. This is exemplified by the oil painting Luxe, Calme et Volupté, completed in the same year.

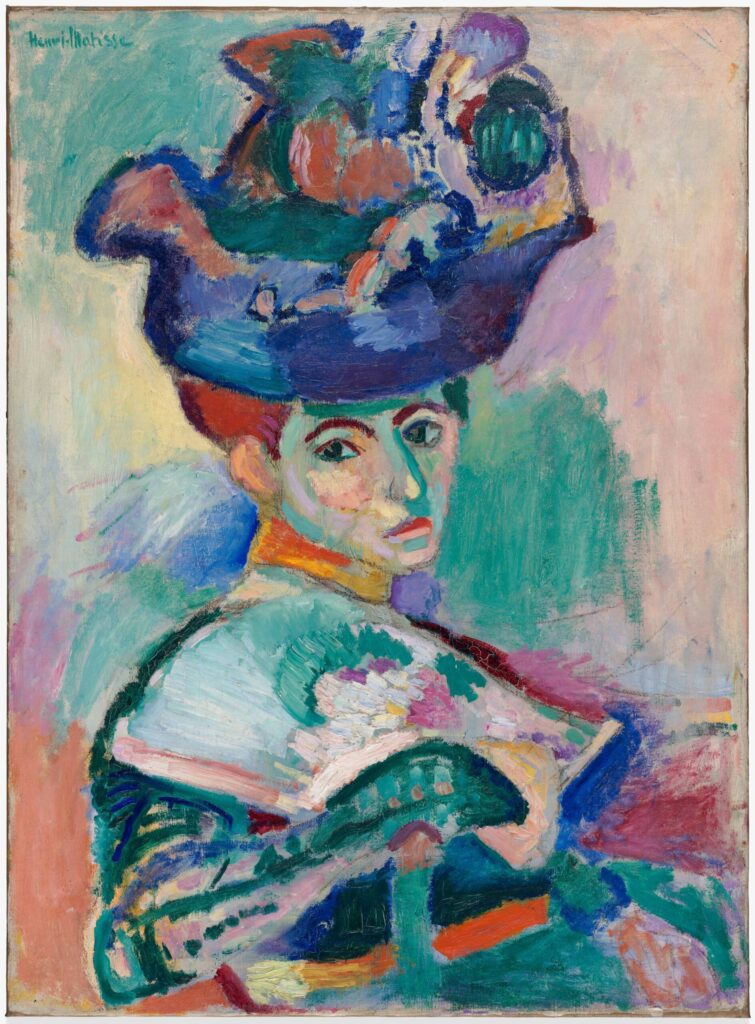

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Henri Matisse, Woman with a Hat, 1905, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA, USA.

In 1905, Matisse painted his most iconic Fauvist work, Woman with a Hat. The subject of the painting is Matisse’s wife, Amélie, exquisitely dressed in an ornate hat and a belt, typical of the French bourgeoisie. His brushstrokes, though, are extremely rough, betraying various degrees of thickness and length, creating the illusion that the work is left unfinished. It was precisely because of the bold and dissonant color scheme and coarse quality that Matisse and other artists were referred to as “fauves.”

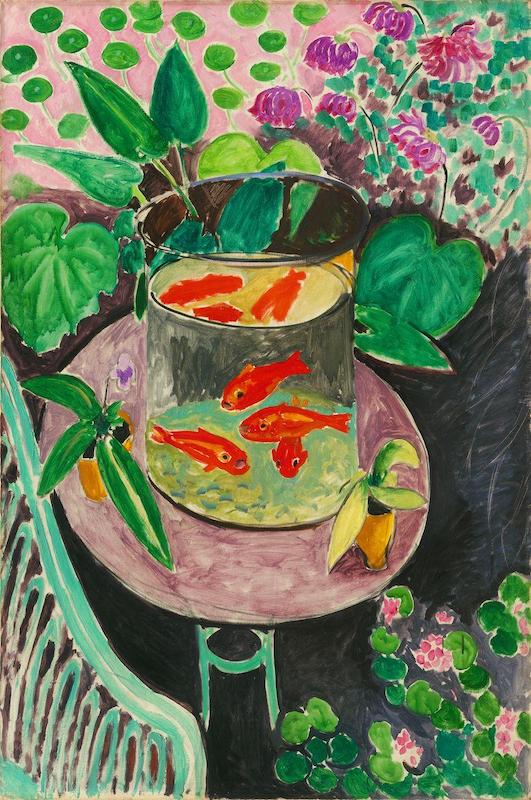

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Henri Matisse, Goldfish, 1912, Pushkin Museum, Moscow, Russia.

The artist traveled to Morocco in 1912, after studying Primitivism and Moorish art in Spain for years. Inspired by the Moroccans’ contemplative lifestyle and particularly their gaze at the goldfish for hours, he painted the Goldfish.

Through contrasting complementary colors and adopting an unusual spatial construction, Matisse deliberately made the goldfish and the vases unnaturalistic. The painting is thus a recomposition of visual elements that leads to a spiritual quest for serenity and relaxation.

Gabriele Münter stood as one of the key figures in the German Expressionist movement. Inspired by Wassily Kandinsky, she nevertheless furthered Expressionism in her own way. Born in Berlin, Münter attended the Phalanx School in Munich in 1901, where she began her expressionist journey.

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Gabriele Münter, Obere Hauptstraße, Murnau, 1908, Collection of Bruce Dayton; Ruth Stricker Dayton, MN, USA.

While taking sculpture courses, she was introduced to Wassily Kandinsky and learned Post-Impressionist techniques. During the two artists’ journey around the Bavarian Alps in 1908, Münter developed a strong interest in vibrant hues and flattened brushstrokes.

The appeal of her imaginative style was so great that even Kandinsky’s landscape paintings drew inspiration from it. As she recalled her experience in the tranquil village of Murnau in Bavaria, “After a short period of agony I took a great leap forward from copying nature — in a more or less Impressionist style — to feeling the content of things — abstracting — conveying an extract.”

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Gabriele Münter, Breakfast of the Birds, 1934, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., USA.

In her later career, the vibrant color scheme was replaced by a more gentle approach, though it was equally passionate and vivid. This is present in Breakfast of the Birds, a 1934 oil paintig that likely presents Münter’s perspective.

Seated in front of a table with bread and plates, she gazes at the serene and charming winter scene outside. The warmth of the red and yellow birds contrast with the whiteness of the tabletop and the exterior sight, conveying both pleasure and solitude—this is precisely the “inner life” of paintings that she aimed to capture.

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Gabriele Münter, Woman in Thought II, 1928, Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY, USA.

She made the same attempt when painting portraits, a genre less commonly explored by other artists of Der Blaue Reiter. In the work Woman in Thought II, she found a balance between an “accurate portrait” that reflects the likeness of her subject and a “good picture” that expresses the contemplative world. As a female artist, Münter possessed an understanding of human nature that male expressionist artists did not always grasp.

In the German Expressionist movement, another artists group named Die Brücke flourished in parallel with Kandinsky and Münter’s Die Blaue Reiter.

One of the founders of Die Brücke was Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Studying at the Royal Technical University of Dresden in 1901, he became an architecture student with an increasing interest in art.

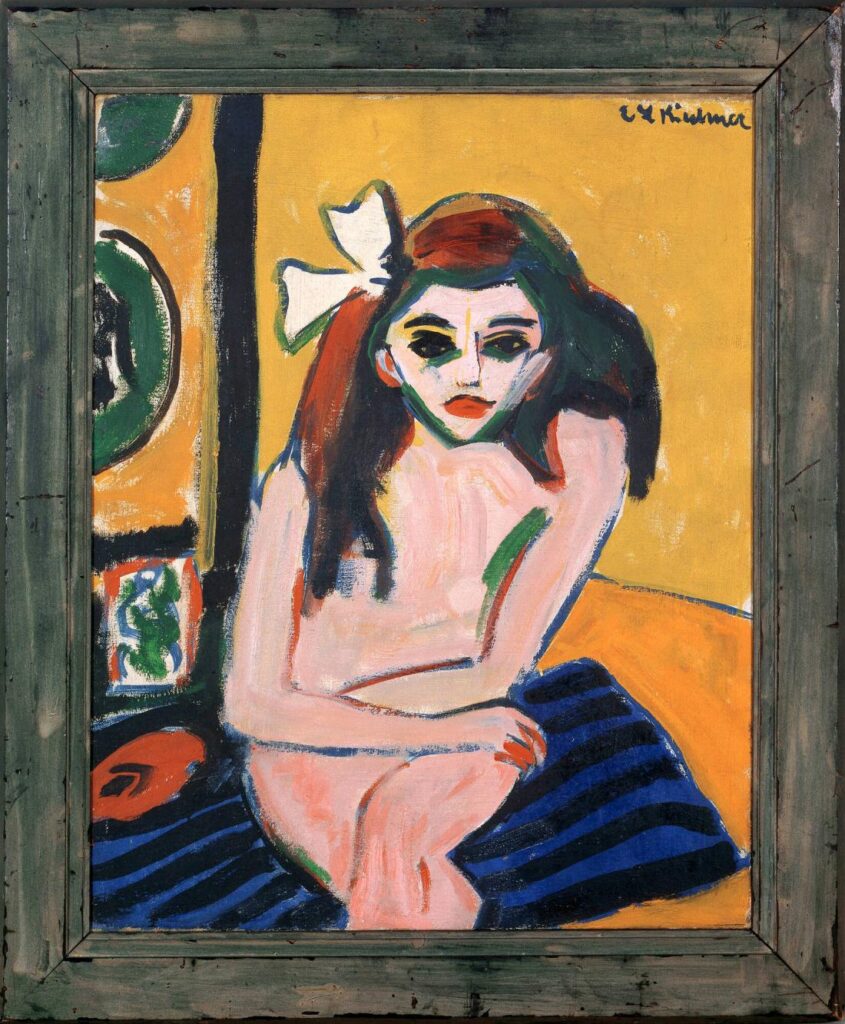

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Marzella, 1909-1910, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden.

With some of his other architecture students, Kirchner established the group Die Brücke in 1905, stating his distaste for the tedious academic tradition and aiming to build an artistic bridge between the past and the present. He was determined to create a future free of antiquated customs and had a fervent belief in the creativity and imagination of the youths. The group, however, did not last long.

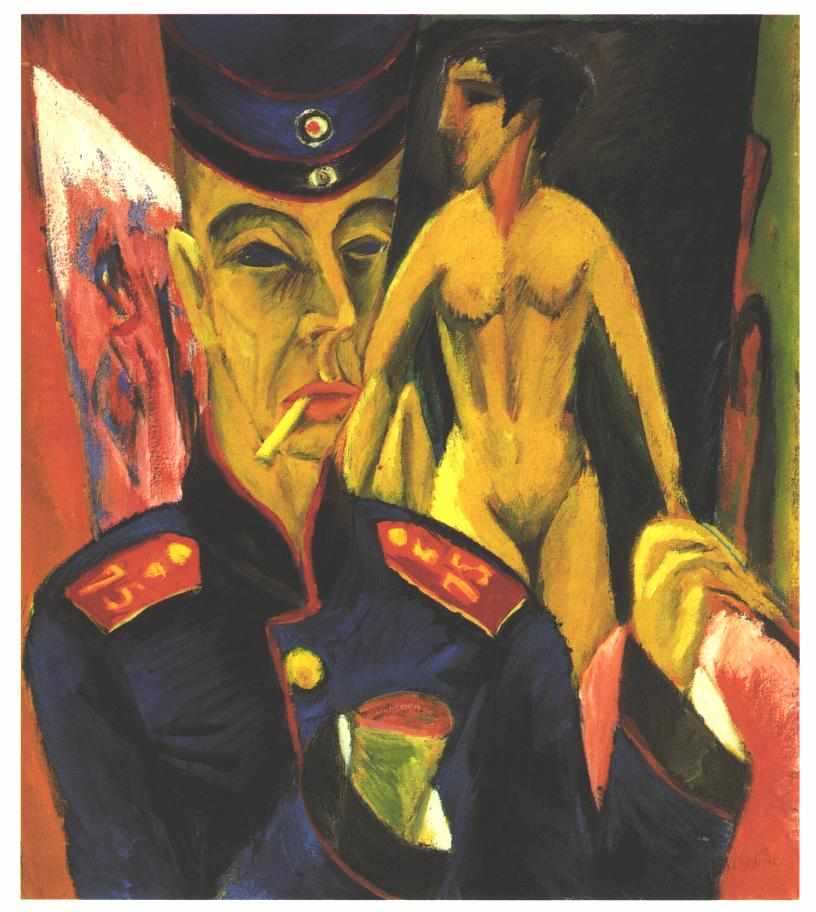

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Self-Portrait as a Soldier, 1915, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, OH, USA.

In 1914, Kirchner volunteered to join the German army, only he suffered from a nervous breakdown and returned to Berlin. Although he never fought on the battlefield, the war became a traumatic experience for him. His emotional struggle was fully expressed in his Self-Portrait as a Soldier, painted a year after the outbreak of the war. The contorted face, depicted as a synthesis of geometric shapes and devoid of humanness, reflects the artist’s deep anguish.

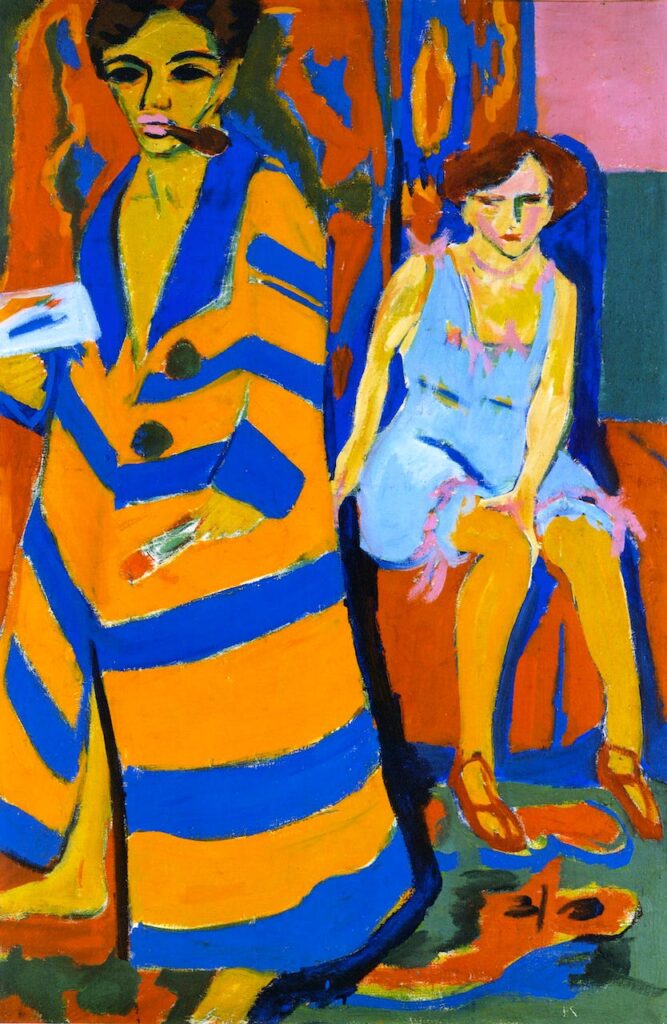

5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Self-Portrait with a Model, 1910, Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany.

Compared to Kircher’s Self-Portrait with a Model, his Self-Portrait as a Soldier reflects a dramatic transformation. The figure’s face, then brimming with vigor, turns dark and pale.

Dressed in a military uniform, the artist is portrayed as a veteran who finds his art career terminated because of his mutilated right hand, representing Kirchner’s deepest fear that his identity as an artist would be threatened. Such a distressful fate befell him two decades later when his artworks were labeled as degenerate by the Nazis, and he died by suicide in affliction.

Author’s bio:

Yi Xin grew up in Beijing and is currently a junior at Beijing Huijia Private School. As an art history student, he is enthralled by Classics, architecture, and philosophy. He’s also an earnest admirer of the Renaissance Republic of Florence and its beautiful coat of arms.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!