5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

Édouard Manet (1832–1883) was a French modernist painter. His paintings have been heavily critiqued and ridiculed by art juries and critics at the peak of his early successes, thus giving birth to many scandalous controversies in 19th-century Parisian cultural life. Realizing the transition from Realism to Impressionism, his artworks have inspired the future of generations of artists. Today, we celebrate his contributions to the universal cultural heritage and remember him as the father of modern art.

Édouard Manet, Self-Portrait with Palette, 1879, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Manet’s father planned for his son a career in the navy; Manet sailed in 1848 on a training vessel to Rio de Janeiro. However, after failing the navy training school entrance exam, he moved to Paris to become an artist. There, he studied under the supervision of the French master Thomas Couture (1815–1879). Spending countless hours at the Musée du Louvre during his apprenticeship, Manet tried to learn from the Old Masters by copying their work. Finally, in 1856, he opened his own studio. In his early years, Manet’s style gravitated towards a somber realism, with loose brushstrokes, adopting in his early works contemporary subjects, such as beggars, bullfights, and people in cafés, whereas in his later works he experimented with different subjects, still lifes, and landscapes.

The jury of the Salon rejected in 1863 Manet’s first major controversial masterpiece, Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l’herbe). That year, the jury was ruthless, rejecting over half of the submissions. Therefore, Le déjeuner sur l’herbe debuted at the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Rejected), a parallel exhibition initiated by Emperor Napoleon III, where all of the artworks rejected by the Salon have been exhibited. The painting stirred both laughter and harsh critiques from the public, which was deeply alarmed by the mundane setting in which such a scene took place. At the time, although widespread but rarely admitted, sex workers used to meet with their clients in French parks.

Manet had a fine sense of humor. In this painting, the artist portrayed four people having a picnic in nature. The two men are fully clothed, however, one of the women wears a revealing dress, while the other is nude. Masterfully, Manet included three genres of portraiture, landscape, and still life in one single artwork. Some art historians believe that the impressive female nude is Victorine Meurent, possibly Manet’s favorite model, who frequently posed for his projects, including for the famous Olympia.

Édouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe), 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

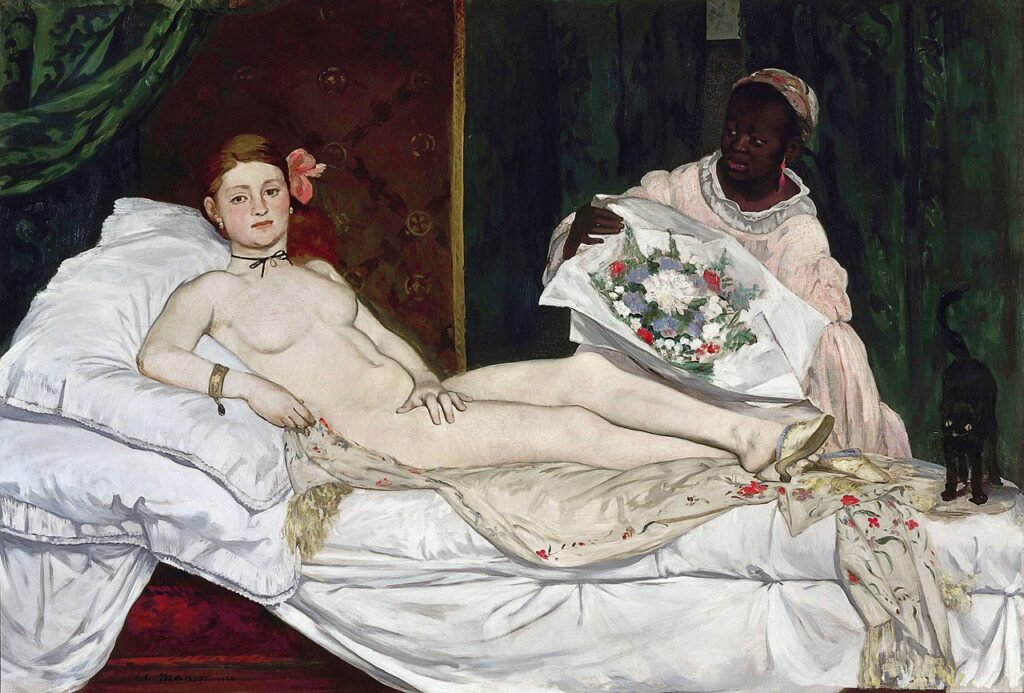

Surprisingly, Manet’s Olympia was accepted in 1865 by the esteemed Salon. The painting depicts a naked woman casually resting on an unmade bed, her look piercing the canvas. A servant brings her a bouquet, while in the far right corner, a black kitten seems to stretch at Olympia’s feet. Several details in the picture indicate that the attractive femme is a sex worker: the slippers she wears in bed, the luscious silk flower behind her ear, her jewelry (the bracelet and pearls), and even the fragrant bouquet — a gift from her patron. Even more so, her name, Olympia, was associated in the 19th century with prostitution.

Manet was inspired by Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Goya’s Maja Desnuda. The artist challenged the academic tradition and painted with strong, definitive brushstrokes, rendering the harsh lighting which embeds the composition. At the time, art critics were scandalized by Olympia‘s boldness, advising pregnant women to avoid the picture! To them, Olympia was an unfinished profane painting.

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Manet enjoyed painting Spanish subjects and loved having fun with them. He dressed his models in Andalusian costumes and gave them Spanish props. For example, in The Spanish Singer, the left-handed model plays on the nonexistent chords of a guitar meant for right-handed musicians, whereas in Mlle V. . . en Costume d’Espada, he costumed Victorine Meurent as a male matador with impractical shoes for bullfighting.

In August 1865, Manet traveled to Spain to flee the thunderstorm of violent reactions from Parisian art critics. Before coming to Spain, he already had a deep appreciation for Spanish culture and artists such as Francisco Goya (1746–1828) and the Spanish master Diego Velázquez (1599–1660); an appreciation fueled by his time at the Louvre spent copying Velázquez’s work. After one of his tours to Prado, Manet wrote:

[Velázquez] didn’t astonish me but ravished me.

Even though Manet refused to call himself an Impressionist painter and declined to participate in any Impressionist exhibitions, his art style inspired the Impressionists and vice-versa. He did not wish to be seen as representative of the movement and preferred to exhibit at the Salon. However, Manet befriended many Impressionist painters such as Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Berthe Morisot, who eventually married his younger brother. Like the Impressionists, he was interested in Plein-air painting and modern subjects, immortalized with quick, suggestive brushstrokes in mundane scenes from everyday life. Many art historians consider Manet to be the first proponent of modern art.

Manet’s portraits are evocative and sentimental, transporting the viewer many decades back in time. His artworks feature a variety of subjects, from friends and family to his fashionable contemporaries, such as famous actresses, bourgeoisie women, and models. Manet portrayed his subjects in a seemingly spontaneous and carefree manner.

His health plummeted near the end of his life, and he moved to the Parisian suburbs, where he continued painting until his death. Manet began in his terminal years a series of portraits on the theme of the four seasons, of which he managed to finalize just two, Spring and Autumn. Even so, his last artwork was A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

Although his works have been ridiculed and rejected by the Salon throughout his life, within a year of his death, an exhibition of 179 of his paintings, pastels, drawings, and prints was organized at the École des Beaux-Arts in his honor. Manet had the courage to break free from the classical canons of painting, his influence in the artwork being immeasurable.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!