Summary

- Candace Wheeler is the “mother” of interior design.

- Elsie de Wolfe let the sunshine into the dark American homes.

- Syrie Maugham made interiors for the elite.

- Dorothy Draper introduced “Hollywood Regency”.

- Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky createed a kitchen for a modern woman.

1. Candace Wheeler

Candace Wheeler (1827-1923) is often called the “mother” of interior design. Throughout her career, she was associated with Colonial Revival, Aesthetic Movement, and the Arts and Crafts Movement. In 1877, together with Louis Comfort Tiffany, John LaFarge, and Elizabeth Custer, she founded the Society of Decorative Arts in New York. The goal of society was to help women support themselves through handicrafts. Next, in 1878, she helped launch the New York Exchange for Women’s Work. This had a broader scope, as it did not require the artistic skills of women.

In 1879 Candace Wheeler and Louis Comfort Tiffany co-founded the interior-decorating firm, Tiffany & Wheeler. The firm decorated a number of significant late-19th-century houses and public buildings, including the Veterans’ Room of the Seventh Regiment Armory, the Madison Square Theatre, the Union League Club, the George Kemp house, and the drawing room of the Cornelius Vanderbilt II house. They also designed the interior of Mark Twain’s house.

Women Interior Designers: Photo of Candance Wheeler, c. 1870. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Women Interior Designers: Tiffany & Wheeler, Dining room design, 1881, Mark Twain’s House Museum, Hartford, CT, USA. Mark Twain’s House.

Next Steps

Candace Wheeler did not stop at that. In 1883 she founded Associated Artists, a textile firm involving only women who produced tapestries and curtains. It was also very famous for “changeable” silks, so-called because the textile was woven using two threads which meant that the textile changed color depending on the light.

In 1892 together with her husband and brother, she founded an artist colony in Catskills Mountains called Onteora. This offered a haven for a number of single women, many of whom were artists or writers, striving towards financial independence. Then in 1893, Wheeler, unstoppable as ever, was asked to serve as the interior decorator of the Woman’s Building at the Chicago World’s Fair. Here she organized the State of New York’s applied arts exhibition.

Women Interior Designers: Candace Wheeler, Onteora Colony interior, 1892, Catskills, NY, USA. Brownstoner.

2. Elsie de Wolfe

Women Interior Designers: Cecil Beaton, Elsie de Wolfe in her Paris apartment wearing a Schiaparelli. Another Mag.

Work

According to The New Yorker, “Interior design as a profession was invented by Elsie de Wolfe”. This may be a slight exaggeration, but it cannot be denied that she was one of the first to become famous for her designs. De Wolfe transformed the interiors of wealthy homes from dark wood, heavily curtained palaces into light, intimate spaces. Her designs featured fresh colors and included 18th-century French furniture and accessories.

Early Life

Elsie de Wolfe (1859-1950) started her career as an actress. She didn’t have any great success or failure but it was the staging of the plays that drew her into the world of interior design. As a result, in 1903 she abandoned her acting career to become an interior decorator. Her clients included Amy Vanderbilt, Anne Morgan, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Henry Clay, and Adelaide Frick.

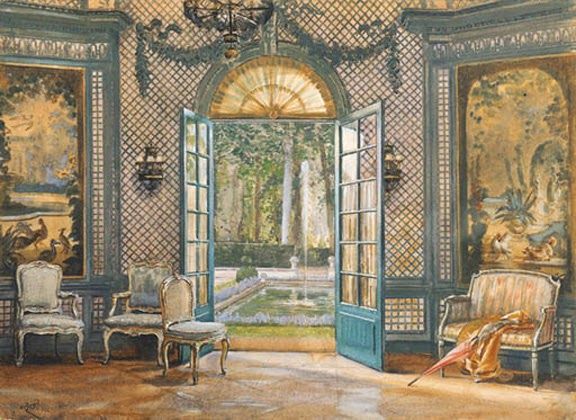

Women Interior Designers: Elsie de Wolfe, The Trellis Room at the Colony Club, 1905, The Colony Club, New York, NY, USA. Architectural Digest.

The Colony Club

The commission for which she became most famous was the interiors of the Colony Club. In 1905 Stanford White, the architect of the club and De Wolfe’s friend, helped her secure the commission. The building became the premier women’s social club and much of its popularity was due to de Wolfe’s interior design. Instead of the heavy, masculine overtones then common in fashionable interiors, De Wolfe used light fabric for window coverings, painted the walls in pale colors, tiled the floors, and added wicker chairs and settees. As a result, the effect gave the illusion of an outdoor garden pavilion. This style full of light and reminiscences of nature is typical of her other designs. In her own words:

I opened the doors and windows of America, and let the air and sunshine in.

Women Interior Designers: Elsie de Wolfe, Coe Hall, Teahouse, 1915, Planting Fields Arboretum State Historic Park, Oyster Bay, NY, USA. House Beautiful.

Life

Elsie de Wolfe was a free spirit. Throughout her life, she remained in a relationship with Elizabeth Marbury though that did not stop the marriage of convenience with Sir Charles Mendl. Apparently, she enjoyed being called Lady Mendl immensely. However, Elsie was famous not only for her work but was also one of the best-known women in New York society. Unsurprisingly, when she moved to Paris she instantly became as prominent there.

It is said she had taffeta pillows embroidered with the motto: “Never complain, never explain.” From the early 1900s, she started excluding red meat from her diet. This gradually evolved into her having a fully vegetarian diet. She also embraced yoga practices. In her memoir, she describes her early morning routine with yoga, standing on her head, and walking on her hands. Elsie de Wolfe certainly feels like a force of nature.

Women Interior Designers: Elsie de Wolfe, Interior of the villa of Countess Dorothy di Frasso, c. 1936, Beverly Hills, CA, USA. Colour Complex.

3. Syrie Maugham

Women Interior Designers: Photo of Syrie Maugham, 1901. Wellcome Images (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Early Years

Syrie Maugham (1879-1955) was a British women’s interior designer who was very popular in the 1920s and 1930s. Known as the “Princess of Pale” she advocated glamour interiors decorated mostly in shades of white. She was born Gwendoline Maud Syrie Barnardo. Her father, the philanthropist Thomas John Barnardo, was the founder of Dr. Barnardo’s Homes for destitute children in the UK. Her mother was the daughter of a Lloyd’s of London underwriter.

It was only in 1922, when she was 42, that she opened her first business, Syrie Ltd: prior to that, she had been an apprentice at Thornton Smith. Her list of clients included Noël Coward, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli and the poet Stephen Tennant.

Women Interior Designers: Syrie Maugham, Bathroom in the Georgian house of Duchess of Argyll, 1930s, Mayfair, London, UK. House and Garden.

Style

Maugham is famous for her groundbreaking “all-white” rooms of the 1920s and 1930s. The most famous was the all-white music room at her home on London’s King’s Road, which she unveiled at a midnight party in 1927. This was a space that variously hosted the Prince of Wales, Cecil Beaton, and the editor of Vogue. You can clearly see she had a knack for marketing her style.

Women Interior Designers: Syrie Maugham, all-white London drawing room, London, UK. The Library Time Machine.

Other designers also considered her a great source of high-quality furniture. Many of the pieces were custom-made and reflected her distinctive style. She advocated very stylish interiors but also designed them with relaxation in mind; they were full of deep chairs and sofas where one could comfortably recline.

Women Interior Designers: Syrie Maugham, pair of cream-painted rope-twist foot stools, c. 20th century, private collection. Christie’s.

Life

Maugham was married twice. Her first husband was Sir Henry Wellcome, who made his fortune in pharmaceuticals but is now probably better known as the founder of the Wellcome Collection. However, the marriage was not too happy and Maugham had many affairs and, predictably, it ended in divorce. Next, in 1917, she married W. Somerset Maugham, having given birth to his daughter Mary Elizabeth in 1915. Unfortunately, this marriage didn’t fare much better, as Maugham spent much of his time separated from his wife. Finally, in 1928 they divorced.

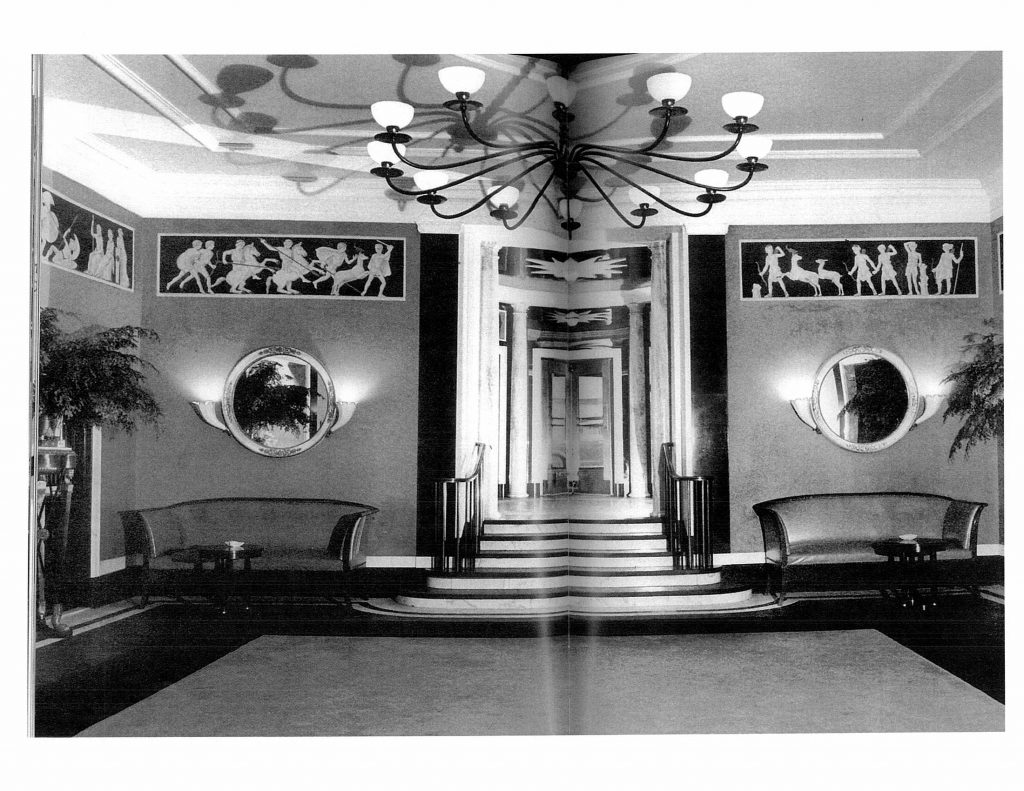

4. Dorothy Draper

Women Interior Designers: Peter Vitale, Dorothy Draper, 1958. Flower Mag.

Dorothy Draper (1889-1969) was one of the American designers, sometimes called “The Duchess of Bold”. Draper was yet another larger-than-life character on our list. Born and raised in an upper-class Tuckerman family, she made full use of the benefits of her class. One such benefit was to provide her with a network of future clients. Her travels and education exposed her first-hand to the historical styles she later employed so freely for her own purposes. What is more, her origins gave her confidence.

Women Interior Designers: Dorothy Draper, The Greenbrier Hotel, 1946-1948, White Sulphur Springs, WV, USA. Curbed.

Style

Dorothy Draper’s style is totally anti-minimalist, sometimes described as “Modern Baroque” or “Hollywood Regency”. However, you can also find it described as “Scarlett O’Hara drops acid”. She employed bold colors and plenty of decoration which are certainly not for the faint-hearted. Draper hated pastel colors and it also seems that she was afflicted with horror vacui (filling the entire surface of space with detail). She shared insights on design in her books, encouraging women of the house to take the decoration into their own hands. She advocated courage and confidence: “if it looks right, it is right” was her motto.

Women Interior Designers: Dorothy Draper, The Greenbrier Hotel, 1946-1948, White Sulphur Springs, WV, USA. Architectural Digest.

Hotels and Resorts

After redecorating her own house, Draper opened the Architectural Clearing House in 1925. Her idea was to connect women seeking to redecorate their homes with architects. Over time and as a result of crises, she evolved and made her name her brand, renaming the company Dorothy Draper Incorporated. Her first large commission was the lobby of the Carlyle Hotel in 1928. It was also her first venture into the niche that she was to make her own – hotel and resorts interior design.

In that same year, she proved she had a gift for delivering amazing results at a decent cost when she took on Sutton Place. The tenements were dirty, and no one wanted to rent there. Using a simple trick of painting the building black with elegant white windowsills, she converted its image. She decorated the interiors with flowered wallpapers and carpets and suddenly people were willing to pay four times more to rent there.

Women Interior Designers: Dorothy Draper, Lobby of the Carlyle Hotel, 1928, New York, NY, USA. InsideIDe.

Her Crowning Glory

Draper then focused on hotels and resorts, with many notable projects. But her crowning glory will remain probably the Greenbrier Hotel in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. She transformed this 600-room hotel in 16 months, making monumental changes for which she was paid handsomely. She charged the highest fee ever paid to a decorator: the cost of the renovation was $4.2 m. Additionally, her company, run by Carleton Varney, still provides design services to the hotel to this day. The décor is busy – you could describe it as loud – with a multitude of strong colors and patterns. One thing that has to be said; you cannot mistake Dorothy Draper’s style for anyone else’s.

Women Interior Designers: Dorothy Draper, The Greenbrier Hotel, 1946-1948, Greenbrier County, West Virginia, USA. Digs.

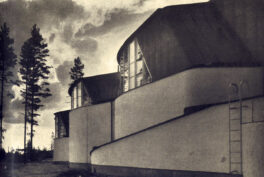

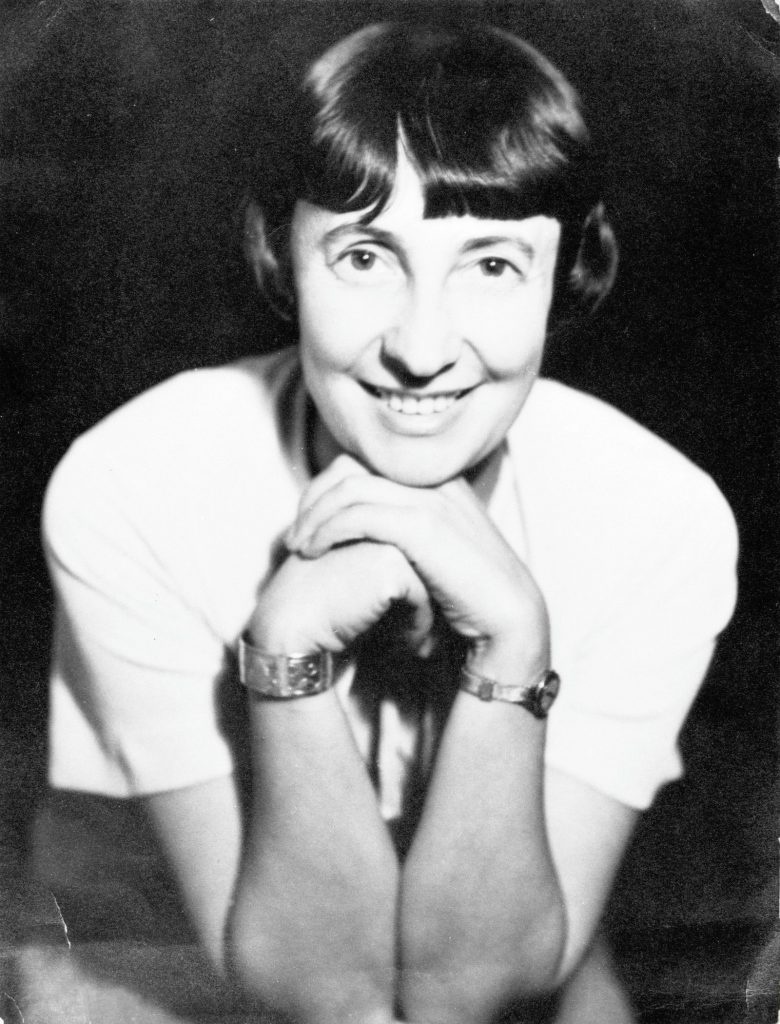

5. Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky

Women Interior Designers: Photo of Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, 1935. Spiegel.

Work

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (1897-2000) may not have changed the stylistic side of the 20th-century design as much as the previous women interior designers we’ve seen. However, what she did was revolutionize our daily lives, with her Frankfurt Kitchen design. This was the prototype of the built-in kitchen now common throughout the western world.

She used a railroad dining car kitchen as her model to design a “housewife’s laboratory” which uses the minimum space whilst offering maximum comfort and equipment to the working mother. The Frankfurt City Council eventually installed 10,000 of her mass-produced, prefabricated kitchens in newly built working-class apartments. As a point of interest, Lihotzky could not cook when she designed the kitchen. When she lived with her family her mother did the cooking and later she went out to eat.

Women Interior Designers: Margarete Schutte Lihotzky, The Frankfurt Kitchen, 1926, Frankfurt, Germany. Reconstruction of the Frankfurt Kitchen, MAK Vienna Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Influences

You may wonder why you never heard of her. There are several reasons for this, but probably the main one was her political views – she was a communist activist. Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky became the first female student at the Kunstgewerbeschule (today University of Applied Arts Vienna), where artists such as Josef Hoffmann, Anton Hanak, or Oskar Kokoschka were teaching. She studied architecture under Oskar Strnad and was winning prizes for her designs even before her graduation. Strnad was a pioneer of social housing, focusing on affordable yet comfortable residential architecture. Lihotzky was heavily influenced by his ideas and understood the importance of functionality in design.

Women Interior Designers: Margarete Schutte Lihotzky, The Frankfurt Kitchen, 1926, Frankfurt, Germany. Reconstruction of the Frankfurt Kitchen. MAK Vienna Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Next Steps

In 1926 she joined Ernst May in Frankfurt, working on the New Frankfurt project which aimed to resolve the city’s housing shortage. That’s where she worked in her famous kitchen. In 1930, together with May, her husband, and others (known as the May Brigade), they traveled to Moscow. They wanted to help to realize Stalin’s first five-year plan, by building the industrial city of Magnitogorsk. She remained in the Soviet Union until 1937.

Then, together with her husband, she left for Istanbul, where they taught at the Academy of Fine Arts. She also designed kindergarten pavilions based on the ideas of Maria Montessori. During WWII she joined the communist resistance and was arrested by the Gestapo in 1941. She remained in prison until the end of the war.

After the war, she continued working in communist countries, as she could not get any work in Austria, due to her political convictions. She celebrated her 100th birthday in 1997, dancing a short waltz with the Mayor of Vienna and remarking, “I would have enjoyed it, for a change, to design a house for a rich man.”

Women Interior Designers: Margarete Schutte Lihotzky, The Frankfurt Kitchen, 1926, Frankfurt, Germany. Reconstruction of the Frankfurt Kitchen MAK Vienna Museum, Vienna, Austria.