5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

There is a common saying that behind every great man, there is a great woman. It was no exception for the legendary sculptor, generally considered the progenitor of modern sculpture, Auguste Rodin. Meet the great Camille Claudel.

Camille Claudel was a sculptress. Among the sources and inspirations for her work were Donatello, Cellini, and Greco-Roman mythology. It was not an easy task for a woman to become an artist in the mid-19th century. She had to cope with moral prejudice and gender-related restrictions in her artistic training, as well as the prevailing male dominance in the Ministry of Fine Arts and Salon juries.

She also had to deal with a tumultuous affair with Auguste Rodin. Some believe it was the reason for her gradual descent into madness.

Camille always wanted to become an artist. She attended classes at the Académie Colarossi, on the Rue de la Grande Chaumière, because the most prestigious École des Beaux-Arts did not admit women at this time.

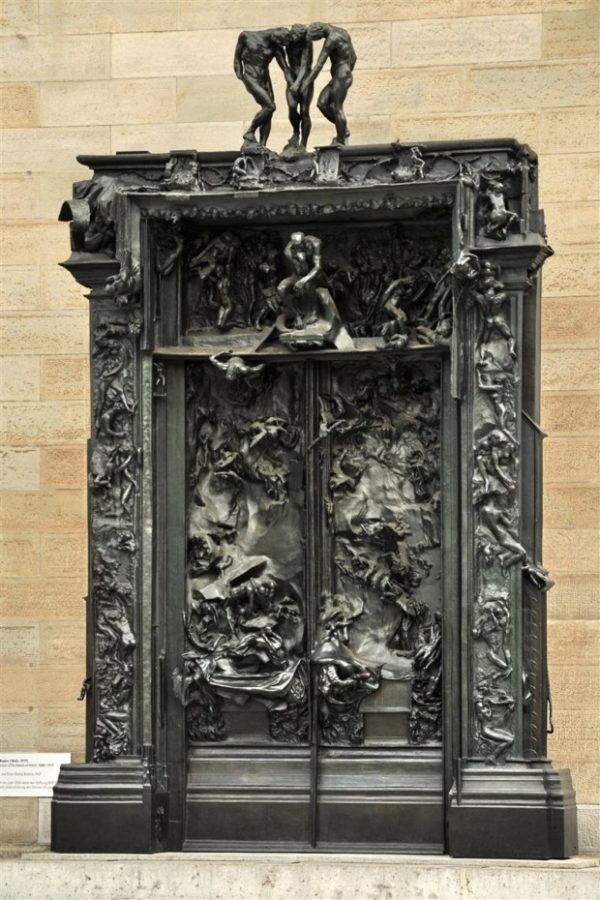

When Rodin received his first major commissions in the early 1880s, he gathered a team of assistants to work alongside him in his studio. Camille turned up in the artist’s working studio as a young, 19-year-old student ca. 1884. It seems that she spent most of her time on complex pieces, such as the hands and feet of figures for monumental sculptures – including the famous The Gates of Hell. She sought recognition as an independent artist at the Salon. Between 1882 and 1889, Claudel regularly exhibited busts and portraits of people close to her at the Salon des Artistes Français.

The two sculptors’ complicated love story has inspired many romanticized interpretations. This intense love affair, encompassing their personal and professional lives, inspired both artists. Rodin modeled several portraits of the sculptress, including Camille Claudel with Short Hair and Mask of Camille Claudel. I Am Beautiful and Eternal Springtime, intended originally for The Gates of Hell, is proof of how passionately Rodin felt about Camille.

There was one problem, however. Rodin had been in a relationship with Rose Beuret for the past 20 years, whom he didn’t want to leave. Claudel never lived with Rodin, and from time to time, she felt the need to keep some distance between them. For example, when Claudel returned from a refuge in England, Rodin was so happy to see her again that he signed an extraordinary “contract” promising that she would be his only pupil and swearing to be faithful to her.

In 1892, after having had an abortion, Claudel ended the intimate aspect of her relationship with Rodin, although they saw each other regularly until 1898.

Claudel could not get the funding to get many of her daring ideas realized due to their sexual element. Thus, she was forced to depend either on Rodin or collaborate with him and let him get the credit as the lionized figure of French sculptures. Rodin consequently signed a number of her works. She also depended on him financially since after her wealthy and loving father died, her mother and brother, who were suspicious of her lifestyle, kept the money and let her wander around the streets dressed in beggars’ clothes.

After the break between Camille Claudel and Rodin, the latter tried to help Camille indirectly and obtained a state commission for her from the Director of Fine Arts. The Age of Maturity was commissioned in 1895 and exhibited in 1899. However, the bronze version was never ordered, and Claudel did not deliver the plaster model. It was Captain Tissier who finally commissioned the first bronze in 1902. After Rodin saw The Age of Maturity for the first time in 1899, he reacted with shock and anger. As such, he suddenly stopped his support for Claudel completely. He even might have put pressure on the Ministry of Fine Arts to cancel the funding for the bronze commission.

The group evokes Rodin’s hesitation between Rose, who finally wins the race, and Camille who is reaching forward to stop him from leaving her. The details of her personal story aside, Camille produced a thought-provoking symbolic work about human relationships.

After 1905, Claudel appeared to be mentally ill. She destroyed many of her statues, went missing for extended periods, exhibited signs of paranoia, and was diagnosed with schizophrenia. She accused Rodin of stealing her ideas and of leading a conspiracy to kill her. Her family closed her in an asylum. Doctors tried to convince them that she shouldn’t have stayed in such an institution, but they still kept her there. The hospital staff regularly proposed to Camille’s mother and brother Claudel’s discharge, but they adamantly refused each time.

Camille Claudel died on 19 October 1943, after having lived 30 years in the asylum. In September 1943, her brother, Paul, had been informed of his sister’s terminal illness. After some difficulty, he crossed occupied France to see her but was neither present at her death nor at her funeral. Her body was interred in the cemetery of Monfavet. Her remains were buried in a communal grave at the asylum.

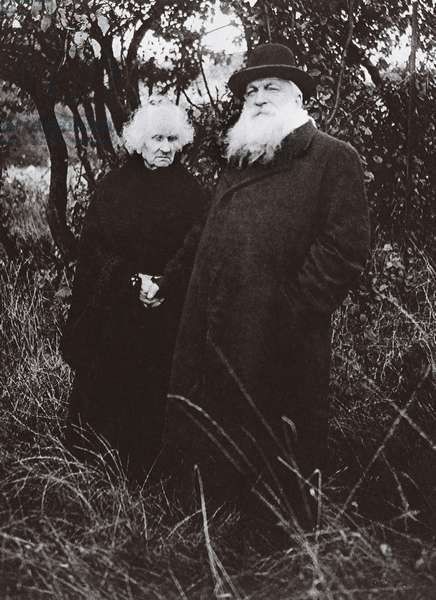

How about Rodin? After 53 years of their relationship, he married Rose Beuret. The wedding was on 29 January 1917, and Beuret died two weeks later. Rodin himself was ill that year; in January, he suffered weakness from influenza and soon died.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!