Masterpiece Story: The Pineapple Picture

Known as the “pineapple picture,” this enigmatic 17th-century painting captures the royal reception of King Charles II. The British royal...

Maya M. Tola 3 September 2024

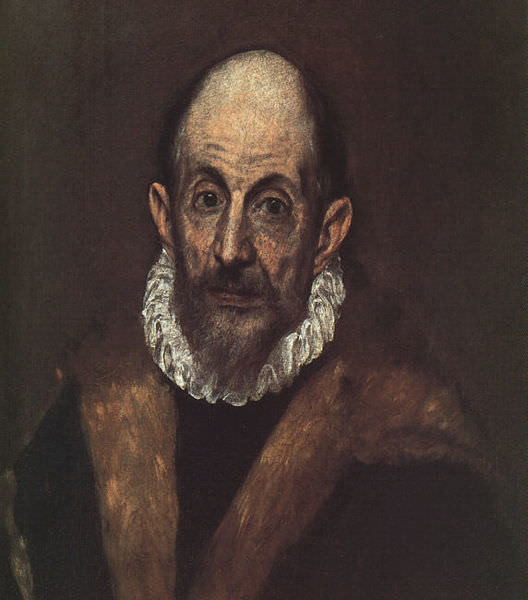

The guide to the Prado Museum describes El Greco as a “philosopher, as an intellectual and as a sensitive and idiosyncratic artist.” It is these qualities, inherent in his individual style, that make him the direct ancestor to modern art. It is striking how the Expressionists of the 20th century really seem to look on this great artist as a grandfather figure.

Domenicos Theotocopoulos was born in Crete in 1541. He began as an iconographer and specialized in symbolic works. As Crete was part of the Republic of Venice, he moved there in 1567 and then on to Rome in 1570. His condemnation of Michelangelo earned him some enemies in Rome so he moved on to Toledo in Spain where he finally met with the success.

Domenicos Theotocopoulos was given the nickname “El Greco”, meaning “the Greek” in Spanish, and it is by this name that he is now known.

The story of Laocoön (the mythical priest of Troy who warned that the wooden horse sent by the Greeks as a gift might be a trick and who was punished by the gods) was a perfect story for El Greco to portray.

The gods have sent serpents to attack Laocoön and his sons. The writhing snakes match the agonies that the men are enduring. The elongated bodies, a feature of El Greco’s work, are grey as if all life is draining out of them. The landscape of Troy lies behind them, the skies thick with heavy laden clouds creating a sense of doom and apocalyptic nightmare.

Ludwig Meidner’s almost prophetic telling of the devastation that was to engulf Europe in two years time may be a little far-fetched but Meidner’s work was a wonder. In it the earth is tearing apart, vegetation is dead and dying, and the bodies lie among the wreckage of the landscape. It is hard not to link it to what was to occur, especially when you notice the smoking volcano in the top right-hand corner. This destruction of humanity, the pain of the contorted figures, and the palette of black, green, and cream come together in a show of what Meidner could see through his studies of the Book of Revelations.

Another work that appears to pick up on El Greco’s elongated, writhing figure painting is this 1918 work by Ludwig von Hofmann, a Swiss Expressionist. Entitled Zusammenbruch, meaning “breakdown,” this painting was originally thought to be an earlier work but research showed that it was painted in 1918 and is felt to be symbolic of the destruction of work. The bodies, like those by El Greco, writhe in agony with arms raised in a pleading manner. Can they be saved?

In El Greco’s Vision of Saint John the same gestures can be seen and, in particular, the lower figures, look pained and in agony. Set in the period of the Book of Revelations, the figures claw skywards as the skies swirl and bring the end of all. Hofmann’s naked figure has clenched hands and contort with agonies we can barely imagine.

Comparing these to El Greco’s work is quite a natural thing to do. The similarities in palette and composition are overwhelming and it is hard to believe that the three men were not contemporaries.

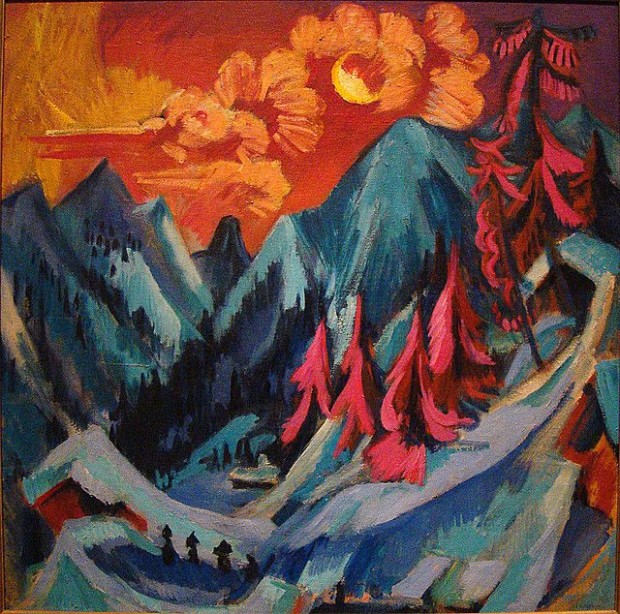

Another area of comparison can be made when exploring landscapes between El Greco and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. These two, El Greco’s Mount Sinai and Kirchner’s Winter Landscape Moonlight.

Although there is a distinct difference in palette choices, what both artists concentrate on is the power of the mountains as a dominant force. The loose brushstrokes create a scene of fear and power. The sheer might and majesty of the mountains reach up into skies that are heavy and laden with foreboding. Trees are dwarfed by these majestic views and it is this viewpoint that helps us to see the energy in both works.

The influence of El Greco was not just limited to the Expressionist movement. Artists as wide-ranging as Van Gogh, Picasso, who went on to paint Les Demoiselles d’Avignon as a direct response to El Greco’s work, and Jackson Pollock, all cited him as an influence. The term “art eats art” can certainly be applied here as all who followed this incredible artist took elements that spoke loudly and made them their own.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!