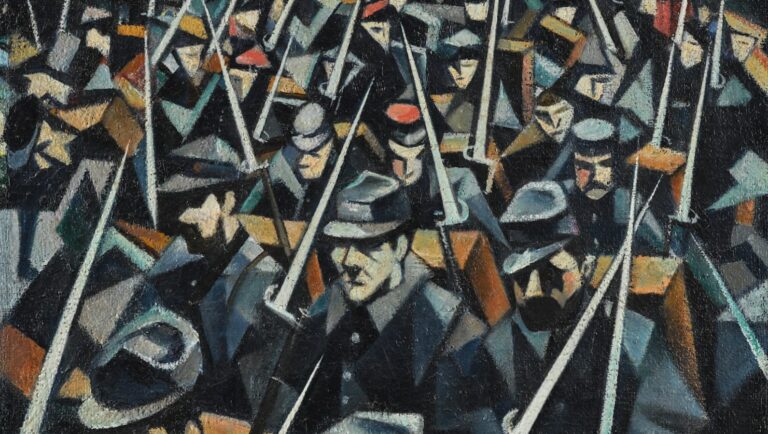

Nevinson aligned himself with the Italian futurists who celebrated and embraced the violence and mechanized speed of the modern age. However, his experience as an ambulance driver in the First World War changed his view. In his paintings of the Front, the soldiers are reduced to a series of angular planes and grey coloring. Here, they appear almost like machines themselves, losing their individuality, even their humanity, as they seem to fuse with the machine gun which gives this painting its title.

The caption from the Tate Gallery.

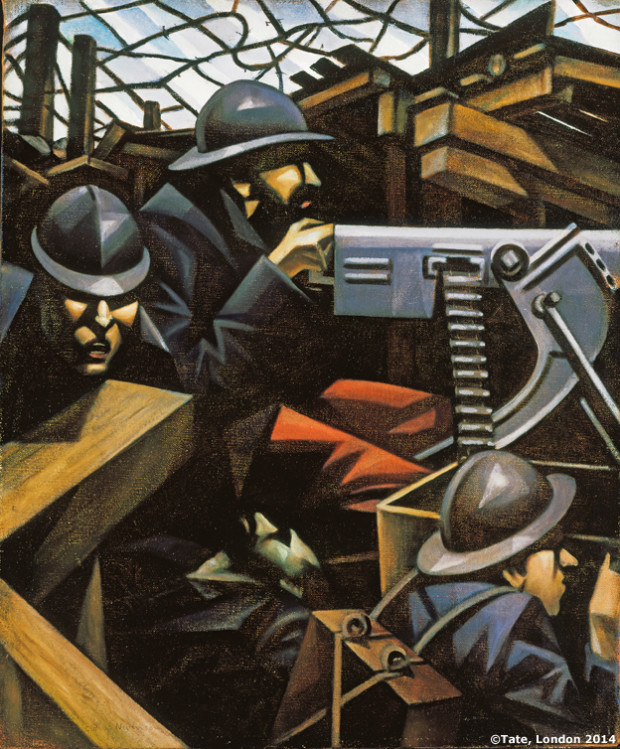

Four French soldiers cramped together in their trench with their mitrailleuse; its cold, grey, metallic body as much at home there as their contorted bodies. Geometric shapes blend both the men with the machine. The gunner stares fixedly over the sights which are outside our frame of vision. His hands gripping the trigger tightly, appearing as if he is part of the gun and the gun is part of him. The angular faces of the three men are determined and focused on the task they are involved in. The body of their fallen comrade is ignored. There is no time to mourn his death. Humanity is lacking in this environment.

In this painting from 1915, the British artist, Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson captures the dehumanising effect that the war machine was creating in the first conflict to utilise the new weaponry. As the caption from the Tate Gallery mentions, Nevinson was an ambulance driver for a short period of time in France and so witnessed, at first hand, what was happening in the trenches and behind the scenes. In his book, A Terrible Beauty: British Artists in the First World War, Paul Gough quotes the poet Laurence Binyon who described Nevinson as depicting ‘a world of men enslaved to a terrific machine of their own making’. In La Mitrailleuse, Nevinson certainly captures the idea of the body being as one with the machine. As an advocate of the Futurist movement who declared that, “We will glorify war —the world’s only hygiene —militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.“, Nevinson’s mood changed when he witnessed the destruction that the man-machine was bringing.

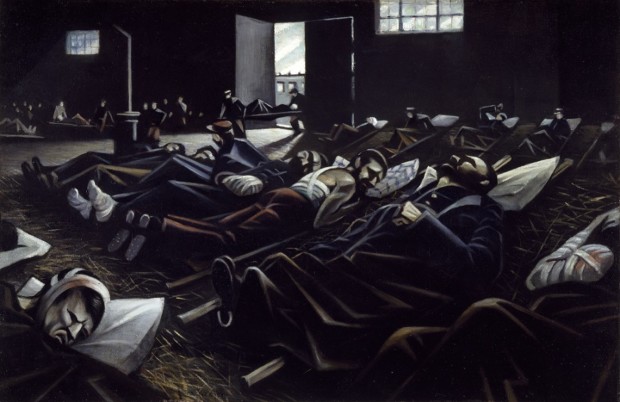

In La Patrie, Nevinson describes a scene that, to the young artist, was horrifying and inspiring at the same time. Nevinson’s ambulance came across a goods yard that resembled something from Dante’s Inferno: dead and dying soldiers, French and German, were laying all over the yard on stretchers. The sights, sounds and smells were terrifying. In his biography, ‘Paint and Prejudice’ Nevinson describes what he saw:

“There we found them. They lay on dirty straw, foul with old bandages and filth, those gaunt, bearded men some white and still with only a faint movement of their chests to distinguish them from the dead by their side. Those who had the strength to moan wailed incessantly:

“Ma mere – ma mere!”

“Oh – la, la!”

“Que je souffre, ma mere!”

The sound of those broken men crying for their mothers is something I shall always have in my ears.”

The geometric shapes of the faces lend themselves to the gauntness that Nevinson describes. Faces are contorted, wrapped in bandages, holding the destroyed faces together. The only light comes from the doorway and through it we can see the clenched hands, gripping filthy blankets, faces wracked with pain. ‘The Shambles’, as this area was known, was a living nightmare for Nevinson:

“When a month had passed I felt I had been born in the nightmare. I had seen sights so revolting that man seldon conceives them in his mind and there was no shrinking even among the more sensitive of us. We could only help, and ignore the shrieks, pus, gangrene, and the disemboweled.”

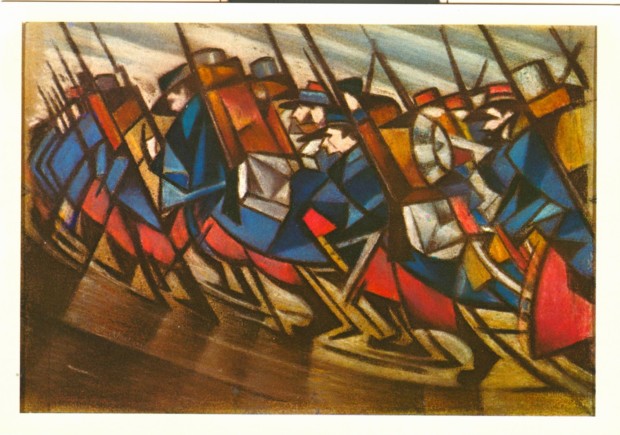

Nevinson was unable to enlist as a soldier; chronic rheumatism meant that he was unable to join a regiment, hence his role as an ambulance driver. He was not close to the front line, but he was able to use his experiences and his observations to good effect. In Column on The March, Nevinson reduces the men further into geometric shapes, marching as one body away into the distance.

The element of movement is very apparent in this version of Returning to the Trenches from 1914: all angles, diagonals; vermilion and cobalt blue of the French uniforms. Nevinson’s use of rhythmic spatial repetition to portray the rapidly marching army reveals how everything was moving forward at an alarming rate. This pastel version of the oil painting, dehumanises the soldiers further, blurring the movement of the men and merging them together.

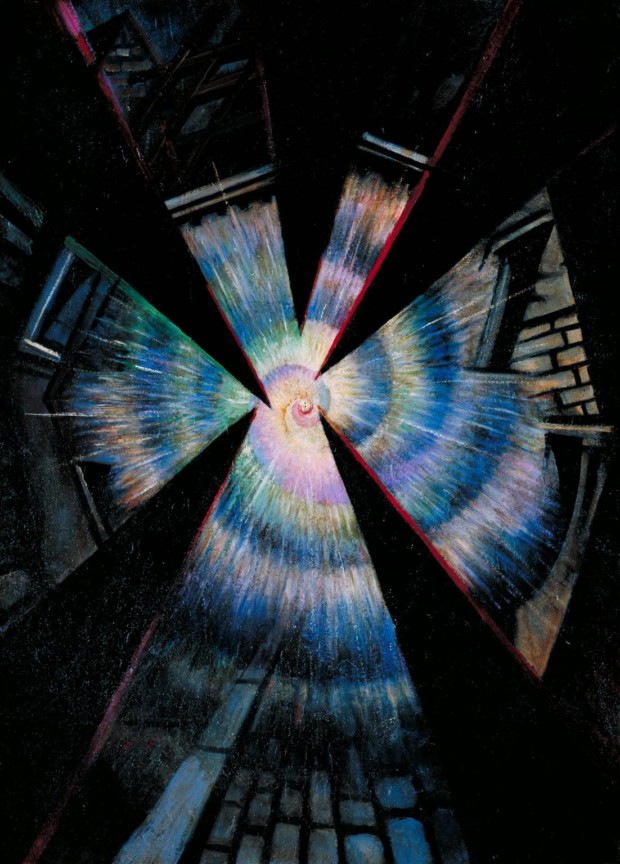

Nevinson did not restrict his view to the battlefield itself. In the 1914 painting, First Searchlights at Charing Cross, Nevinson used a cubist style to bring the buildings to their reduced forms, merging with the sweeping arcs and piercing beams of the searchlights For the Londoners experiencing the war at home, this method of protection against night raids would have been exciting and terrifying at the same time. The use of the blue-grey palette gives the whole scene a cold edge that is in contrast to the red-hot effect caused by a shell blast.

The centre of the bursting vortex spirals outwards in shades of white, pink, violet; the cold white heat of the shell radiates through the spiral: black outlined in red fractures the beautiful shape of the blast. Cobbles and brickwork distinguish the scene as being an urban scene rather than the battlefield. The futurist/vorticist style is so apparent here and adds to the sensory overload that is the only way to experience the event and survive.

Nevinson’s fame grew from his war work, but he felt slighted by the very people he had been working for to express in a new type of art form what warfare was really like. In the catalogue for his first exhibition in peacetime, Nevinson sealed his reputation as a ‘difficult’ man when he wrote:

“I wish to be thoroughly disassociated from every “new”, or “ advanced” movement; every form of “ist”, “ism”, “post”, “neo”, “academic” or “unacademic”. Also I refuse to use the same technical method to express such contradictory forms as a rock or a woman.”

Nevinson began the war ‘enslaved’ to the will of the machine; fed by an “ism. However, by the end, Nevinson, as was his customary stance, went his own way, arguing and standing up for his art to the bitter end.

More information:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”500″ identifier=”B004R9PM1W” locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/41USq2Bvtt3L.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”314″]

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”500″ identifier=”B00IJ0AMRO” locale=”UK” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/51YCH9OxvLL.jpg” tag=”dail005-21″ width=”346″]