When the American figurative painter, George Tooker died in 2011, The New York Times said of his 1956 painting, Government Bureau, “was inspired by his maddening encounter with the New York City Building Department. Most people who waste hours in line just end up with sore feet and headaches. Mr. Tooker, who died on March 27, emerged with one of the best-known depictions of modern alienation and despair.”

Tooker, who was born in Brooklyn in 1920, was greatly influenced by his friend and teacher, Paul Cadmus who encouraged Tooker to use the Renaissance medium of tempera in his works. The luminous quality of the paint helps to create a world that is real, yet not. It is understandable, when you study the works, that Tooker was classed a painter of magic realism. However, the works that clash with this description are the ones that show the alienation and despair that the modern world was seemingly encouraging during the 1950s and 60s and when this is where Tooker comes into his element.

Mechanisation and production line working became the norm in 1950s America. In these paintings, Tooker reveals the darker side of the American Dream; the world of alienation, monotony and bureaucracy.

Government Bureau (1956)

The homogenous faces behind the screens reflect the mundane life of the office clerk, “Good morning, sir/madam. How may I help you today?” The round lights above their heads are in rigid lines and reflect the circular apertures that the clerks look out of at their customers. Their world is very small and repetitive. The customers line up neatly, calmly, waiting their turn.

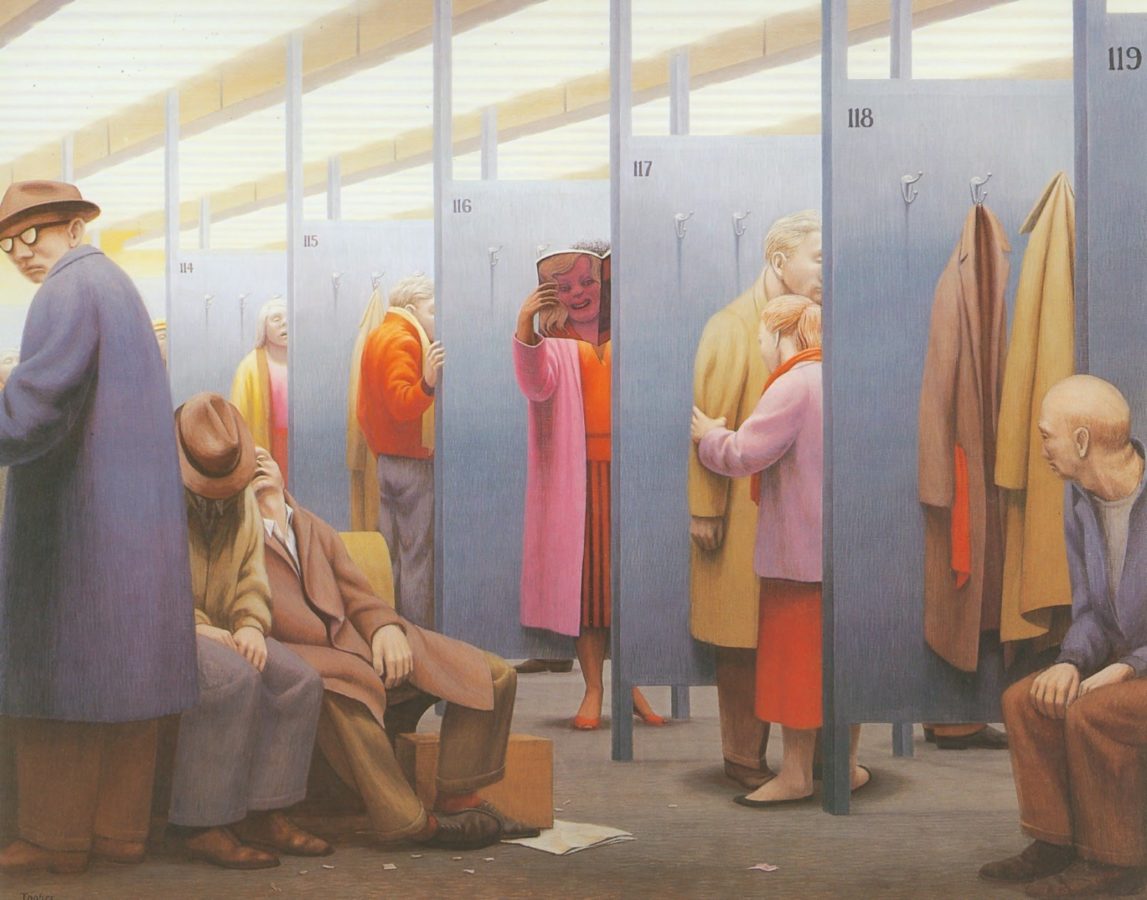

Landscape with figures (1965-66)

Blank, staring faces, monotonous tasks. The same dreariness, day in, day out. Alienation and despair are personified in this work. Boxed in, no one can change anything about their lives. In Landscape with figures; Tooker shows how the office worker is trapped within the setting; almost dehumanising. There is no way in and no way out. All of the workers face the same direction. Two of the employees raise their heads to look straight out of the canvas, staring directly into the eyes of the viewer. They are so cowed by their situation, that their faces show very little emotion, but their eyes fix on ours as if to ask for help to escape. Behind them, the boxes fan out into infinity. There is no escape!

Lunch (1964)

No eye contact is being made in Lunch; not with the viewer or with their fellow diners. The dining area is cropped close to give a claustrophobic feel to this. By reducing the colour palette in this way, Tooker creates a sense of connection between the diners, almost as if they are in uniform and work in tandem with each other. However, the fact that they do not acknowledge each other adds loneliness to the scene; that dreadful feeling of being alone in a crowd.

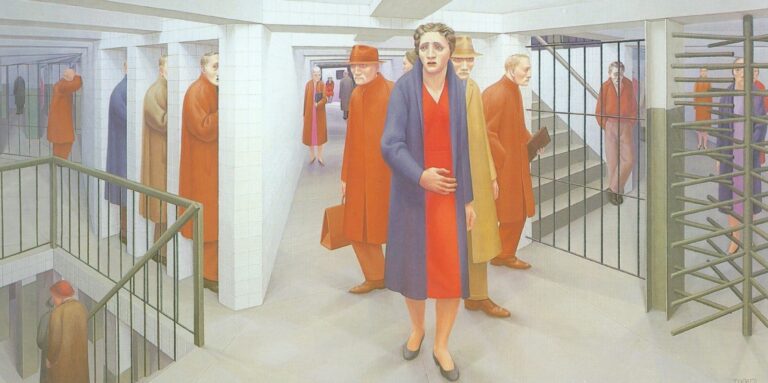

The Subway (1950)

Of all of his work, this iconic image has so much to say in such a tightly composed work. The woman is central in this scene and the men fan out behind her. Her face, full of distress gives this a sinister feel. The composition is dominated by diagonals. People are trapped behind grids; standing in openings and the alienation of modern life is so beautifully captured here. No one makes eye contact with anyone, yet they are linked by the limited colour palette, just like the diners in Lunch.

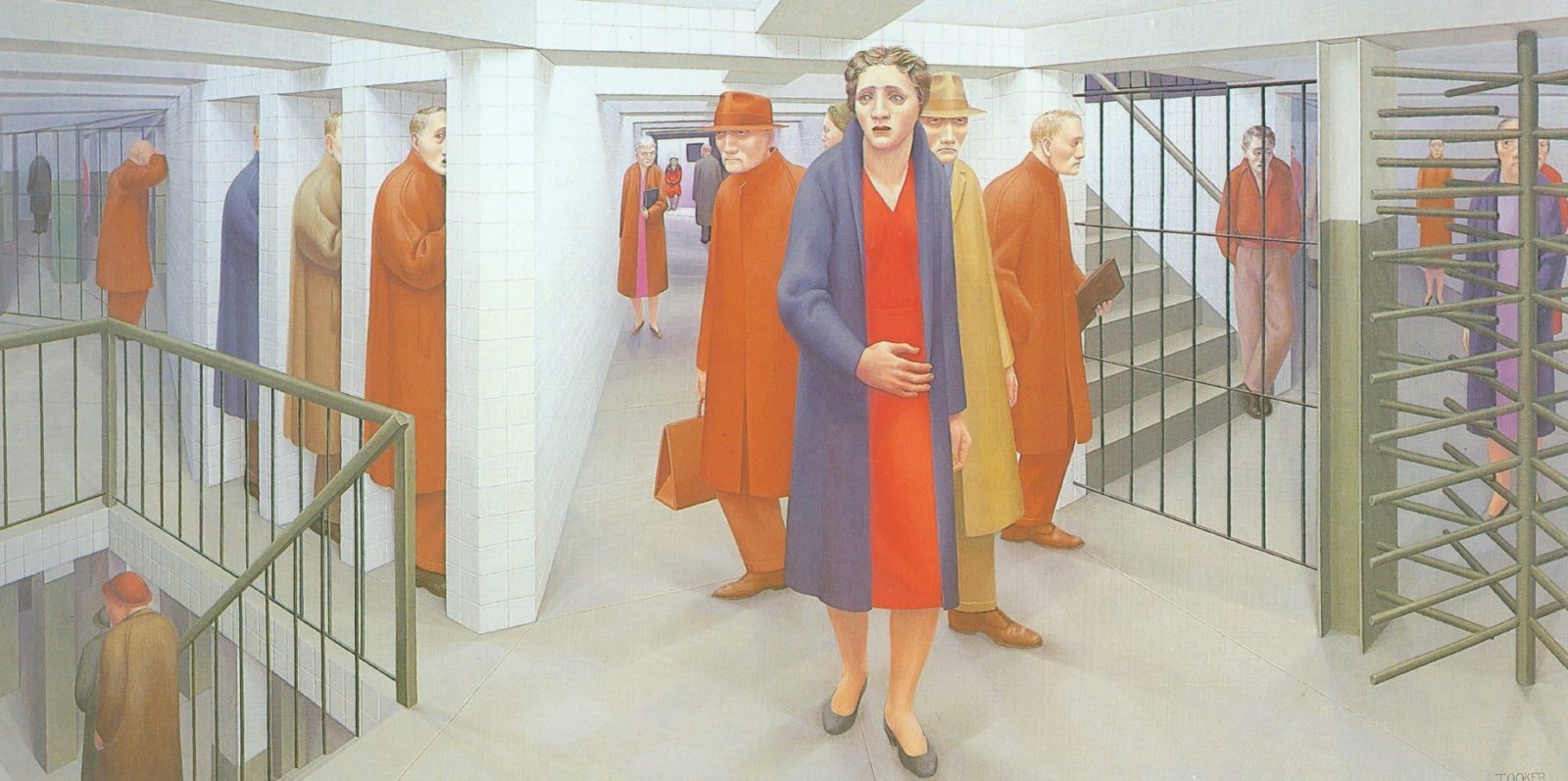

The Waiting Room (1959)

In Waiting Room, the people all seem connected by the colour palette but also by the languid positioning of the figures. The two men seated are sleeping, weary from their long wait. The pose of the man with his head back gives the impression that he is likely to be snoring. Perhaps the man in the bottom right is looking at the embarrassing display in front of him.

It is difficult to place this waiting room, hospital, doctor’s surgery, department store. The cubicles are numbered, men and women are together, coats are left hanging up and the whole scene seems chaotic and untidy. Our man on the left looks out at us as if to ask what we are doing here.

The monotony of waiting seems to be a real strength of Tooker’s: we have all been in that situation and the way in which he anonymises his figures make them ‘every’ man and ‘every’ woman. At no point do any of the people represented in these works appear angry at their waiting, they are so used to the despair they feel that it becomes the norm; an aspect of our busy daily lives, that we seem unable or unwilling to lose.

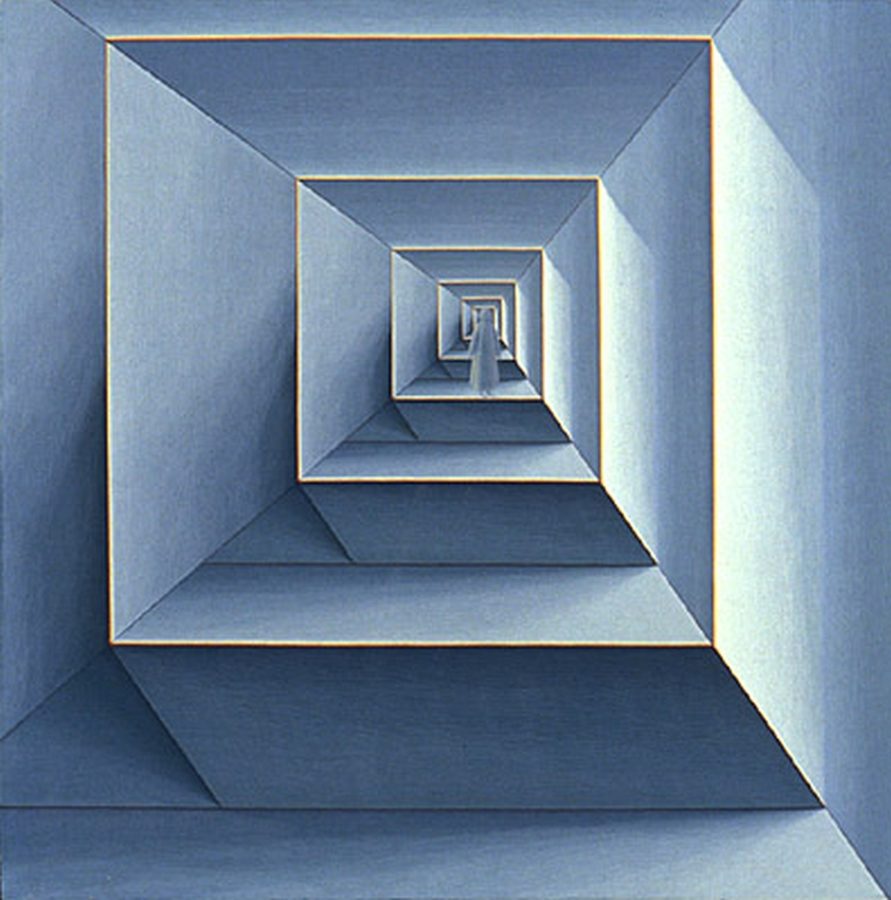

Farewell (1966)

This final work differs from the previous, but the sense of alienation is strong here. The geometric interlocking boxes are in gradients of blue/grey which chill the viewer. As we look deeper into the boxes, we see a figure with its back to us. Faceless, anonymous; it could be any one of us. The symbolism here leads us to think of the end; the passage into the ‘light’. Was all life simply leading to this moment? In an interview with Justin Spring in American Art Magazine in 2002, Tooker said of this painting: “I was thinking of it as reversible space, a corridor and boxes coming toward you. It’s about a state of shock … about how I felt at the time of my mother’s death.”

George Tooker’s artistic output spanned decades and changed in style but what he excelled in never changed: exploring the human condition and the way our environmental impacts on the way we interact with the world; a world full of alienation and despair.

For more information:

-

- https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/07/opinion/07thu4.html

- Spring, Justin, and George Tooker. “An Interview with George Tooker.” American Art, vol. 16, no. 1, 2002, pp. 61–81. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3109396

- GEORGE TOOKER – Painter of Modern Anxieties: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jhrS5n-LzkU

- Documentary produced by Columbus Museum of Art in conjunction with the exhibition George Tooker: A Retrospective:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”1858944562″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/51dPSj8g3ML.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”138″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0982631677″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/51u2BGDV57WL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”132″]