A Chinese painter and Buddhist monk who lived 1612-1674, Kun Can was known as one of the ‘Four Great Monk Painters’ of the early Qing Dynasty.

As a youth Kun Can studied the classics and prepared himself for the civil service examinations, at the same time becoming interested in painting and Buddhism. At age twenty-six he travelled to the Jiangnan region to seek further instruction in Buddhism. He studied under the famous patriarch, Zhuhong, who synthesized the three doctrines of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism. Returning to Hunan Province, Kuncan attained a kind of spiritual enlightenment. In 1654 he resided at the Dabaoen Temple in Nanjing. A few years later in 1659 he moved to the Youqi Temple on Mt. Zutang, not far from Nanjing where he lived the rest of his life.

For the next few years between 1660-63 he journeyed to scenic places in the mountains nearby where he did most of his painting. He continued the long tradition of landscape painting we’re so familiar with when we think of Chinese art.

Everyone loves Chinese landscapes. We see them hanging proudly in Chinese restaurants, and most Chinese businesses have more than one Chinese landscape painting on the wall behind the counter. So, why are they so popular? They’re mysterious. A quick look shows a mountainous scene covered in gnarled trees; misty clouds and waterfalls; and some tiny wooden shelters with open sides revealing a few Chinese people drinking tea. It puzzles our imagination and we’re left wondering if these mysterious places really exist somewhere in the Middle Kingdom. As well there are Chinese characters painted in long rows side by side in an empty space within the picture but who knows what they mean unless you can read Chinese? The viewer will conclude these landscapes are not representational but ideal. Much is implied symbolically.

Chinese landscape artists consciously try to create a harmonious humanist relationship with heaven, earth and the wonders of creation in their compositions.

The light objects are usually mist, snow, water and clouds. The dark objects are usually the mountains and the trees. As well the rustic shelters at various levels on the mountain indicate frugality and the open sides invite neighbors to trust each other. Sailboats in the distance show how important leisure is to the wise people who live here.

Traditionally it’s the inner world of the monk or the scholar that gives Chinese landscape paintings their most important meaning. Kun Can found great inspiration from the painter, Wang Meng (1308-85), who captured the interior world of scholars and monks in their ideal mountain retreats.

Surrounded by the natural energy of mountains and streams the monk’s retreat becomes a place of calm in an idealistic world far away from the shifting terrain of the political world outside. Simple figures and dwellings are protected by overarching mountains and trees, waterfalls and streams, evoking a dream-like vision of paradise.

Kun Can uses calligraphy and poetry to embellish his landscape paintings. The artistically drawn Chinese characters are an essential part of the art. They describe the artist’s intentions in the painting. (The red seals joined to the side of the calligraphy denote other names he gives himself.)

In his painting, Origin of the Immortals, composed with the usual natural elements, he describes the joy of living in seclusion with only the natural world for company. The poem describes his perfectly human feelings at being a monk integrated with mother nature.

I still find joy in this secluded life,

Treading on the path, I find beautiful scenes as I please,

I play my musical instrument as I walk along the river,

Until I enter a fascinating place through the clouds,

The water is deep, and the land is open and flat,

Mountains shine under the sunlight,

The deafening sound of spring covers other noises,

The flat rocks look so clean, as if they have been swept,

I feel so happy I forget my fatigue,

The stream winds all the way up to the high mountain,

When I look ahead, the mountains look as if they are cut,

And the irregular mountain caves are exquisite,

I feel as if I am high in the sky.

My steps feel so light as I walk in the pine woods,

Resting in the mountains, I forget about the material world.

The place is so quiet that even monks don’t come here,

I plan to live here for the rest of my life,

Until I die in the mountain.

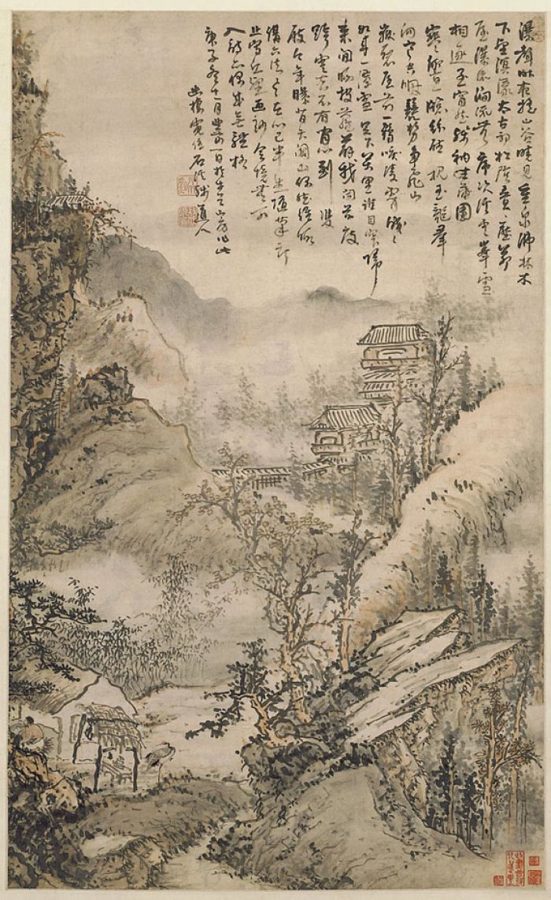

In another painting, Walking Through a Pine Forest at Midnight, the old monk walks along a path followed by his servant who carries a stringed instrument. They’re at the bottom of a high mountain. There’s a waterfall and white mist. Far off we see the tiny sails of three boats on the distant lake. Near the top of the mountain a rustic dwelling is perched at the edge of the cliff where the monk lives.

The calligraphy at the top, very clearly expresses Kun Can’s simple and tender inner life. He calls himself the Immortal of Wuman.

A recluse has built his home on the edge of the blue cliff,

Ten thousand green pines coil before it,

Spring breeze, flowers are picked in handfuls.

Who is the Immortal of Wuman?

His body is already light,

After the elixir of immortality, his spiritual power intensifies.

By day, I sit alone under trees in the wild,

The sea is calm, the dragon does not howl.

Last night, I dreamt of visiting you in the shade of the pines,

Barefooted, I tread the clouds and the slippery mossy stones,

The gusty wind blows the sky, to awaken me.

Returning home, I walk through the pines in bright moonlight.

Kun Can sounds like he’s dreaming with his eyes open. His poem gives the picture its mood: other-worldly, subjective, spiritual but also down-to-earth!

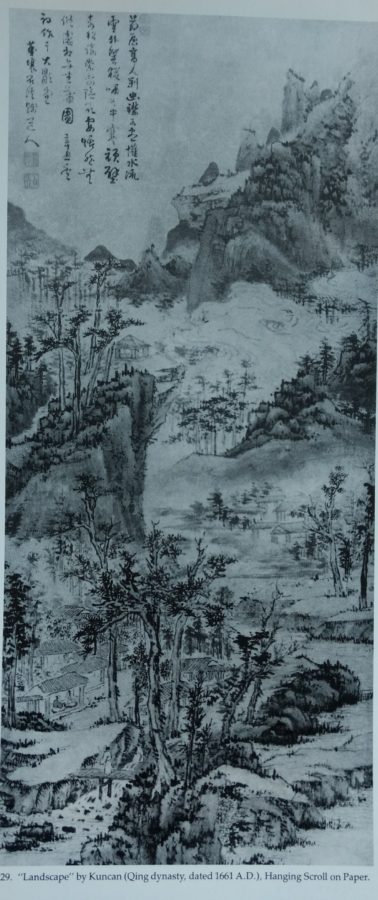

In another painting called, Landscape, we see most of the usual elements of landscape art, but this painting lacks any water. Instead, there’s a huge cloud of mist in the middle and I’m sure I see two large eyes and the shape of a dragon’s face or some other mythological creature dominating the landscape and possibly Kun Can’s imagination.

Kun Can’s paintings are immortal. He captured his inner vision superbly. He personifies the union of man and nature in a most profound combination of mind spirit and heart in his paintings and his poetry.

He didn’t have many close friends during his lifetime but, as happens with many great artists, he’s had many friends throughout the ages and in all parts of the world since then. He’s honored as one of the greatest landscape painters in Chinese art history.

Bibliographic citations:

- Joseph Tseni Chang and Chu-Tsing Li, Kuncan, Oxfordartonline.com, Oxford, 2003

- Nat’l Gallery of Victoria, An Album of Chinese Art, Nat’l Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1983

- Maxwell K. Hearn, How to Read Chinese Paintings, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2008

- Richard R.Barnhart et al, Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1997

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0500202990″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/518250FE9IL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”113″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0520255690″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/51UuTh5dqL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”131″]