The Royal Collection is one of the largest and most important art collections in the world, and one of the last great European royal collections to remain intact.

A press release by the UK’s Royal Collection has marked an important aspect about the arts in Britain that is often overlooked. The Royal Collection comprises of over one million objects collected through the reigns of George I onwards and held in trust for the nation by each subsequent monarch.

For the next two years, the collection’s Trust will be digitising the private papers and items belonging to Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, and the project will reveal the extent to which the Queen’s husband contributed to the artistic and social changes that came about during this period. The press release from the Trust advises that the collection entails:

official and private papers relating to Prince Albert from the Royal Archives and the Royal Commission for Exhibition for 1851; material in the Royal Library, including catalogues of Prince Albert’s private library; inventories of paintings commissioned or collected by Albert; the Raphael Collection, the Prince’s study collection of more than 5,000 prints and photographs after the works of Raphael; and the significant body of early photography collected and commissioned by Prince Albert (more than 10,000 photographs.

It is safe to say that this will be a significant contribution to the cultural legacy that Albert left the nation.

Early Influences

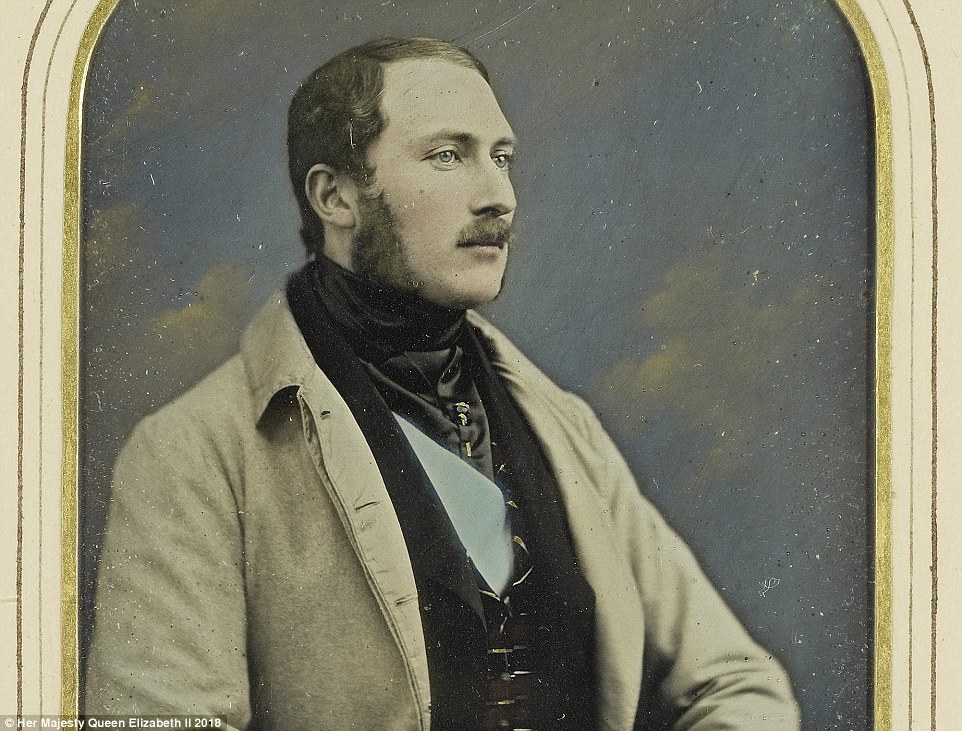

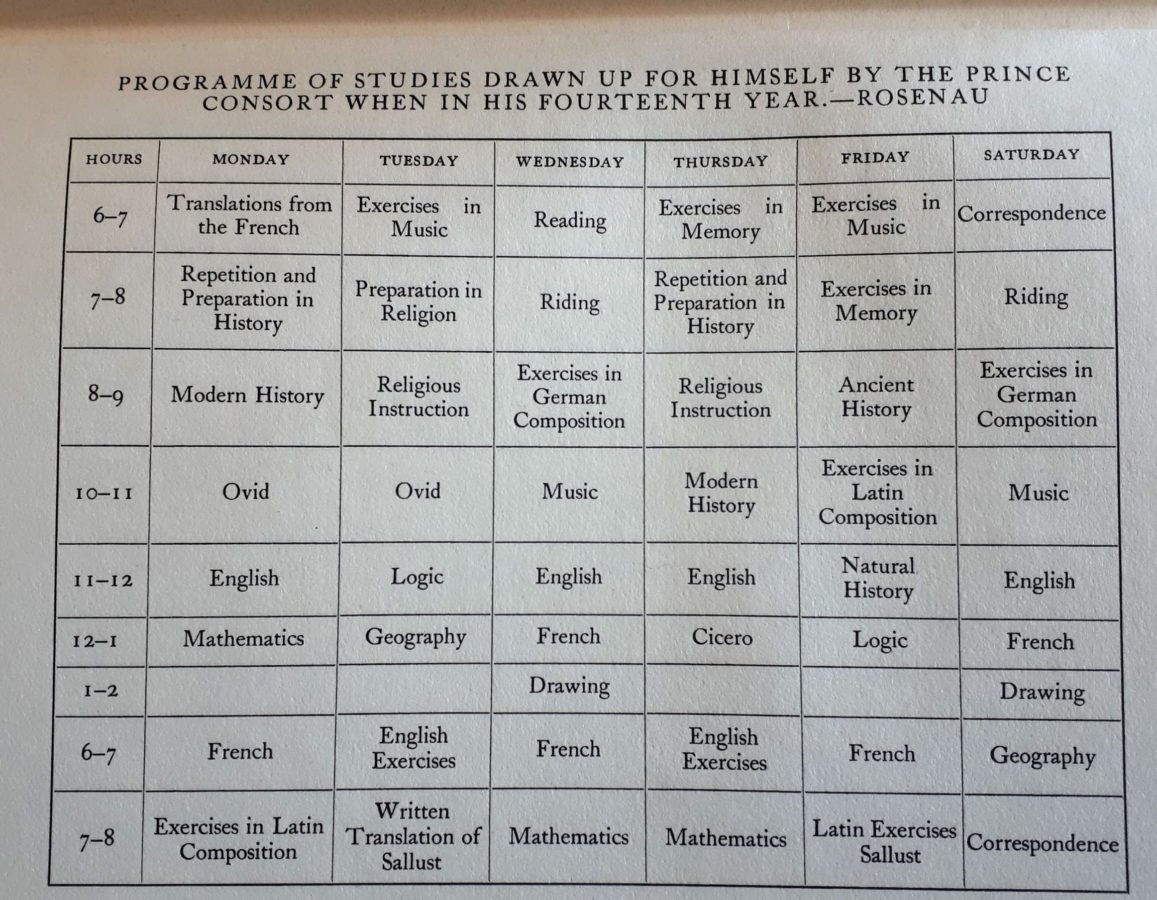

Born in 1819, a few months after his cousin Victoria, Albert’s upbringing in Coburg was typical of its time but there was an added element to it: the Prince’s own love of art and literature, and of learning as can be seen in this timetable created by the Prince himself when he was 14 years old.

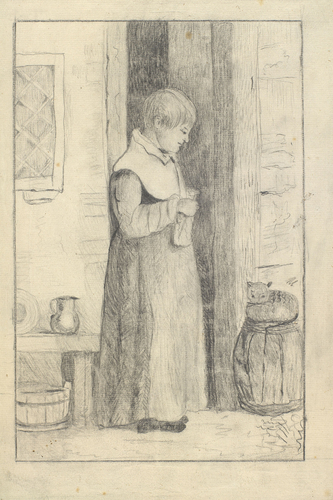

Albert was a keen artist himself as well as a connoisseur of the arts. As with all young privileged men of his time, the visits to important artworks in Italy was part of his education. This pencil drawing from around 1830 demonstrates the eye he had for detail:

Even as an adult, Albert continued to take instruction and learned the art of etching from Sir George Hayter and this delightful etching of the young Princess Royal and her brother, the Prince of Wales, based on a sketch by the Queen, was his first attempt at the art.

When Victoria and Albert became betrothed, they began a tradition whereby they would exchange gifts of an artistic nature. Albert presented a range of gifts: love lyrics by Friedrich Ruckert, portraits in miniature and in marble, and songs, verses and jewellery on the theme of orange blossom; while Victoria gave a portrait of herself.

This commissioning and exchanging of gifts continued throughout their marriage. The Queen had a tendency to give Albert heavily-nude paintings as birthday presents during their marriage – William Edward Frost‘s Una Among the Fauns and Wood Nymphs and The Disarming of Cupid, and Florinda by one of their favourite artists, the German painter Franz Xaver Winterhalter. Florinda hung opposite the Queen’s desk at Osborne.

Albert’s tastes were more with the Renaissance and in the Royal Collection are many pieces that he collected, including this triptych by Duccio Di Buoninsegna:

This love of art is reflected in the way Albert viewed this as an essential part of life and therefore wished to share this with his adopted country and it was a way that he could break the monotony of having no official role. Unable to play any part in political life: he was not King, he was not equal to the Queen; even in her journal she made the comment that ‘Albert helped me with the blotting paper when I signed’, which must have been frustrating to the sensitive and intelligent young man.

It was in the arts, science, trade and industry where Albert excelled and developed a role that had the biggest impact. The writer, Lytton Strachey in his biography of the Queen, was quite dismissive of the Prince but even he had to admit that:

For whenever duty called, the Prince was all alertness. With indefatigable perseverance, he opened museums, laid the foundation stones of hospitals, made speeches to the Royal Agricultural Society, and attended meetings of the British Association. The National Gallery particularly interested him: he drew up careful regulations for the arrangement of the pictures according to schools; and he attempted—though in vain—to have the whole collection transported to South Kensington.

A Royal Chairman

Sir Robert Peel, the Prime Minister quickly realised that this young man was in need of a role and he asked him to be chairman of the Royal Commission to advise the government on rebuilding the Houses of Parliament. The Prince took the commission in his stride and he was instrumental in bringing in artists and sculptors whose works are still enjoyed by visitors today in the seat of British Democracy.

Osborne House

In 1845, Albert and Victoria purchased a house on the Isle of Wight which was intended to be a residence away from royal life. The original house was deemed too small and so, with the support of master builder, Thomas Cubitt, Albert set to work on the design of the new royal home and based it on the Italian ‘Palazzo’ style that so impressed him on his European travels. In addition, the house gave Albert the opportunity to fill it with works of art that appealed to the family’s tastes.

The 1851 Great Exhibition

The life a member of the Royal Family involves being the figurehead to many societies, but for the Prince, these titles were not just ‘honorary’ but had meaning. In his role as President of the Society of Arts, Albert became the lead on an idea that formulated following a visit in 1844 to Paris and the Exposition Nationale.

Therefore, it is with The Great Exhibition of 1851 that the Prince left his mark on the nation. For Albert, there was no better example of a nation leading the way in technology, science and the arts and creating a platform to exhibit all that Britain had to offer became a project that would place the country on the international stage.

The whole project, fraught with objections, money raising events, a competition to design the center cost a total of The ‘Crystal Palace’, as it became known, was designed by Joseph Paxton. The glass construction covered 26 acres and was 564 metres long by 138 metres wide, constructed from cast iron-frame components and glass panels made in Birmingham. Over 6 million people filed through the cathedral-like building to enjoy over 100,000 exhibits from all corners of the world.

In her journal entry of 1st May 1851, Queen Victoria wrote:

‘This day is one of the greatest and most glorious of our lives… It is a day which makes my heart swell with thankfulness… The Park presented a wonderful spectacle, crowds streaming through it, – carriages and troops passing… The Green Park and Hyde Park were one mass of densely crowded human beings, in the highest good humour… before we neared the Crystal Palace, the sun shone and gleamed upon the gigantic edifice, upon which the flags of every nation were flying… The sight as we came to the centre where the steps and chair (on which I did not sit) was placed, facing the beautiful crystal fountain was magic and impressive. The tremendous cheering, the joy expressed in every face, the vastness of the building, with all its decoration and exhibits, the sound of the organ… all this was indeed moving.’

Albert’s dream had become a successful reality.

Legacy

The success of the Exhibition, along with the profit gave momentum to create a museum complex in South Kensington. Many of the items from the Exhibition were used in the first exhibitions to be shown in the Victoria and Albert museum of art and design, which opened shortly followed by the Science Museum in 1857. The cultural quarter became known as ‘Albertopolis’ in tribute to the Prince Consort and the future of the area was secured.

The sudden death of the Prince Consort in 1861 sent shock waves through the royal family. Victoria was plunged into paroxysms of grief that led her to remain in mourning for the rest of her life.

The Science and Arts building was renamed The Royal Albert Hall, and across from the hall, in Kensington Park is the Albert Memorial as a lasting monument to the young man from Coburg who came to marry a Queen but who gave so much to his adopted country.

…it is the loss of a public man whose services to this country, though rendered neither in the field of battle nor in the arena of crowded assemblies, have yet been of inestimable value to this nation.

The Times 16 December 1861

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”1331677343″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/51FY2B74jnhL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”107″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”B00NMBT0H8″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/51Pfe9D2BTLL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”100″]