5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

28 July 2022 min Read

Protest art, especially around war, has a rich global history, in visual art, installation art, in music and in literature. German philosopher Adorno famously said: “all art is an uncommitted crime”, meaning that art challenges the status quo by its very nature.

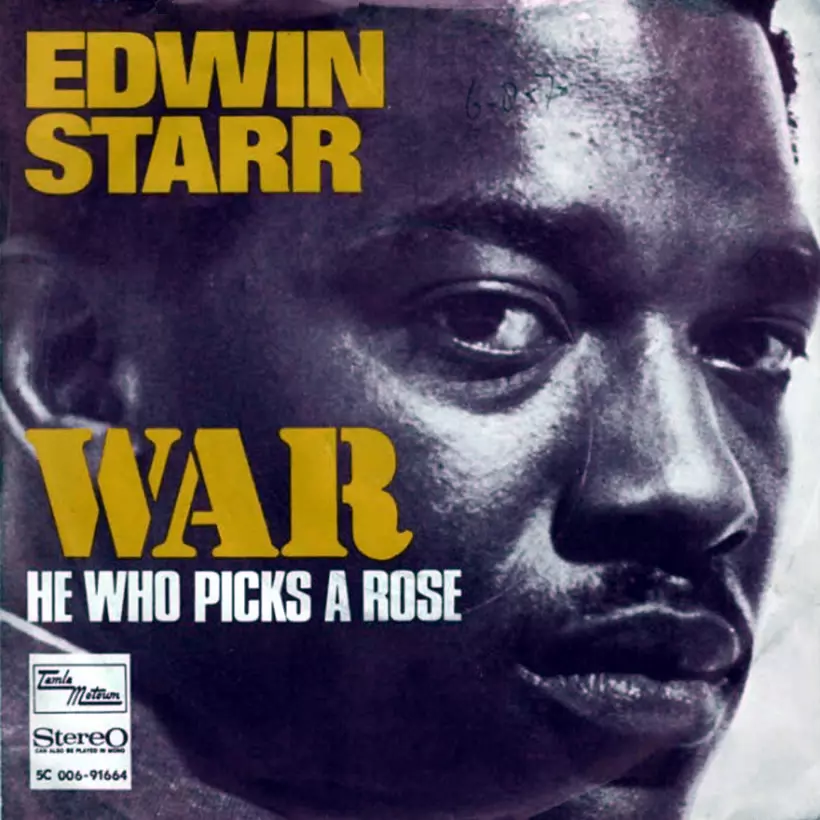

Points are awarded to anyone who recognizes that the lyric in the title is from the 1969 Motown song War by Edwin Starr.

Truly great artists reflect back at us, they look at the culture, social conditions and politics of our society. Art can witness our pain; it can outrage us and provoke us. It can nudge us gently or it can push us over a cliff. Art opens up spaces for the marginalized and the excluded to be seen and heard.

Let’s take a look at two pieces with a complex and interconnected relationship. One from 1930s fascist Spain and one from 1970s capitalist America. So far, so different, but these two artworks, Guernica and And Babies are intimately connected.

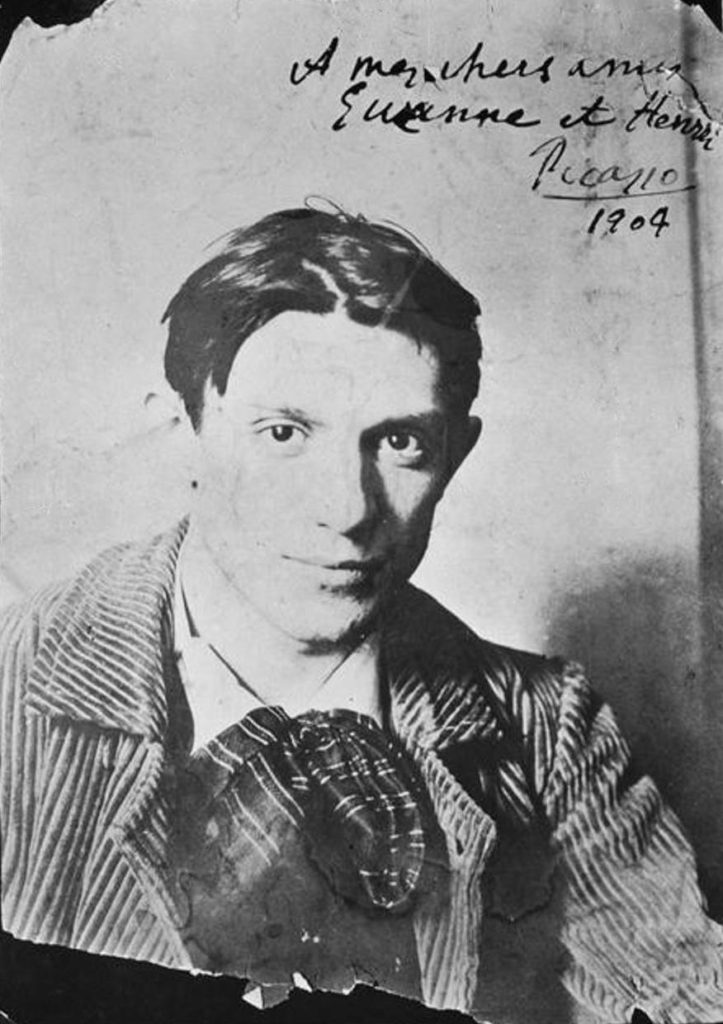

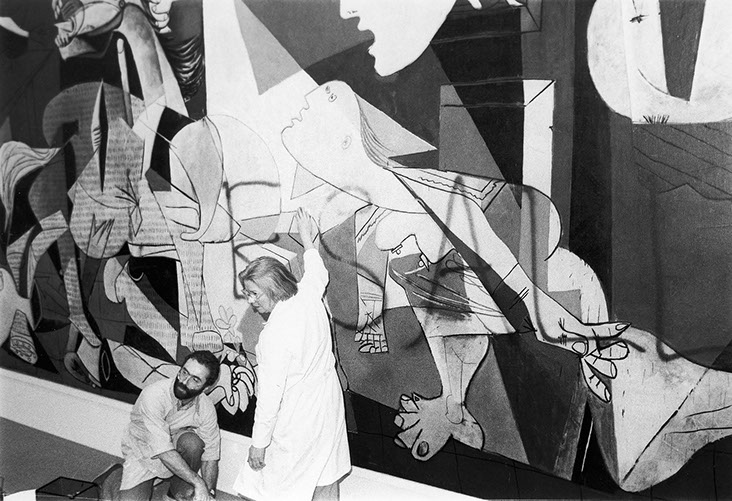

Guernica is a huge, mural-sized oil painting on canvas by Spanish artist Pablo Picasso. Completed in June 1937, it is 3 and a half meters tall and almost 8 meters wide. It is painted in somber shades of black, blue, grey and white.

The painting was Picasso’s immediate and passionate reaction to the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica. It is based on real events, when Guernica was bombed by planes from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The work was widely acclaimed and helped bring world-wide attention to the Spanish Civil War.

In showing the awful inhumanity of war, Picasso’s work provided inspiration to the modern human rights movement, and the work has gained a monumental status as an anti-war symbol.

There is an anecdote about Guernica which sources claim is absolutely true. During WWII, Picasso lived in an apartment in Nazi-occupied Paris, and was visited by a German officer. The Nazi officer was incensed when he saw a photograph of Guernica. He asked Picasso “Did you do that?” Picasso replied “No. You did.”

However, our protest art story does not end with that classic punchline. Guernica continued to play a part in protest art years almost 40 years later.

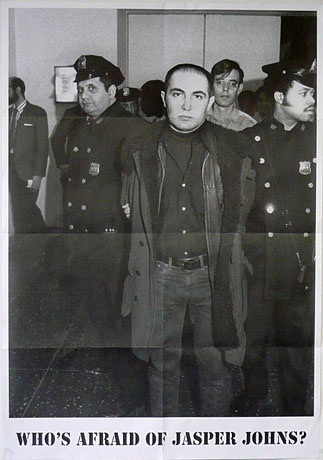

It’s 1970 and Guernica is on display in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Tony Shafrazi, leader of a group called the Art Workers Coalition unfurls a lithograph banner beneath Picasso’s giant mural.

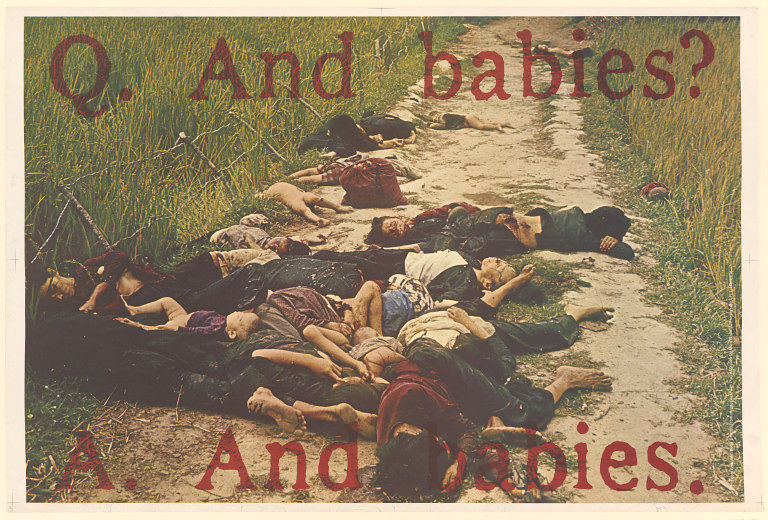

This poster, called And Babies, protests the mass killing of Vietnamese families by American soldiers in 1968 at My Lai. The My Lai massacre prompted global outrage, and the chilling title is a phrase from a television interview with one of the soldiers who was present. Just like Guernica, And Babies vividly depicts the suffering that war inflicts upon innocent civilians. As you’d expect, the photograph used in the lithograph is very disturbing.

Now fast forward four years to February 1974 – and meet Tony Shafrazi at MoMA again.

Brandishing a can of spray paint, he cries out:

Call the curator! I am an artist!

Shafrazi spray-painted red letters, four feet high, over Guernica which said “KILL LIES ALL”, in protest at the release of a US lieutenant, William Calley, who played a part the My Lai massacre. Calley was found guilty of multiple murders at a court-martial but was released within three days on the personal instructions of President Richard Nixon.

As it happens (and as I suspect Shafrazi knew himself), Guernica was covered in heavy varnish and the graffiti did no damage at all. However, his protest made headlines across the world.

Shafrazi said:

I wanted to retrieve the art from art history and give it life. I tried to trespass beyond that invisible barrier that no one is allowed to cross; I wanted to encourage the individual viewer to challenge the art, to see it in its dynamic raw state, not as a piece of history.

Tony Shafrazi, Art Vandals.

Picasso said in 1937:

I express my abhorrence of the military caste which has sunk Spain in an ocean of pain and death.

Pablo Picasso, quoted in Colm Tóibín, “The art of war”, The Guardian.

Almost 40 years later, Shafrazi uses that same horror, that same image, to violently protest the American war machine.

Protest requires a focus, and art gives us a public space where we can have a conversation, with the artist and with each other. Shafrazi was in conversation with Picasso and with us.

The impact of war is shocking; its after-effects have a huge effect on a population. Some artists shy away from vivid representations of this. Others pour their anger out onto the canvas. Or even, like Shafrazi, onto other people’s canvases. As lawyer Michael Ratner said “is this desecration or revitalization?”

How far should artists go in their pursuit of truth? How far would you go?

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!