Masterpiece Story: The Pineapple Picture

Known as the “pineapple picture,” this enigmatic 17th-century painting captures the royal reception of King Charles II. The British royal...

Maya M. Tola 3 September 2024

What do we think of when we ponder the Victorian era? I for one almost always think of steam trains, the Victoria & Albert Museum, Sherlock Holmes, Jack the Ripper, Charles Dickens, pea-soupers (thick London fog), public libraries, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. These are the first things that come to my mind but of course, that’s only me!

Others might rightly mention Oscar Wilde, the rise of the British Empire, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the typewriter, and the invention of photography. What about Romantic Medievalism, the Suffragette Movement, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Punch Magazine, and the serialization of novels in periodicals? The Victorian era is a huge subject and the thought of trying to write an article that covers so much innovation and creativity is quite daunting. So, I’m going to unashamedly cherry-pick different aspects from the era and round it down to my personal favorite five things everyone should know about the Victorians (not necessarily in order of importance). Hopefully, it will create a kind of collage that will provide a brief visual impression of what the Victorian experience looked like!

The Victorian era saw the rise of steam-powered travel. British engineers had been experimenting with the design of steam locomotives from as early as 1784. However, the first properly working model (the Coalbrookdale Locomotive) was built in 1802 by Richard Trevithick, a mining engineer from Cornwall. Locomotive design focused on industrial application, for example the transportation of coal. It wasn’t until 1925 whereupon locomotive design had evolved sufficiently that the Stockton and Darlington Railway Company brought the world’s first public railway into being. From here sprang a national network of railways. A vision of a country linked by rail that had seemed impossible only a short time ago was suddenly a reality. A growing network of lines meant great opportunities for speedy connectivity, meaning that people, goods, and information could be disseminated more widely than ever before.

The evolution of the steam ship was not far behind. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was responsible for 1847’s SS Great Britain which became the first steam ship to cross the Atlantic. John Laird was the first shipbuilder to use iron in hull construction. The SS Archimedes of 1839 was the world’s first steamship to be driven by a screw propeller, the invention of Sir Francis Pettit Smith and John Ericsson. Astonishingly The Enterprize [sic], a paddle-steamer built of wood, was the first steam ship to make the journey from England to India as early as 1825.

Turner’s painting above, Rain, Steam and Speed (1844) really captures the excitement of the rise of steam power in Victorian Britain. The train seems to cut through the natural landscape like an unwanted and brutal presence, but at the same time it emerges from it like something newly born, a mark of hope and a sign of the future.

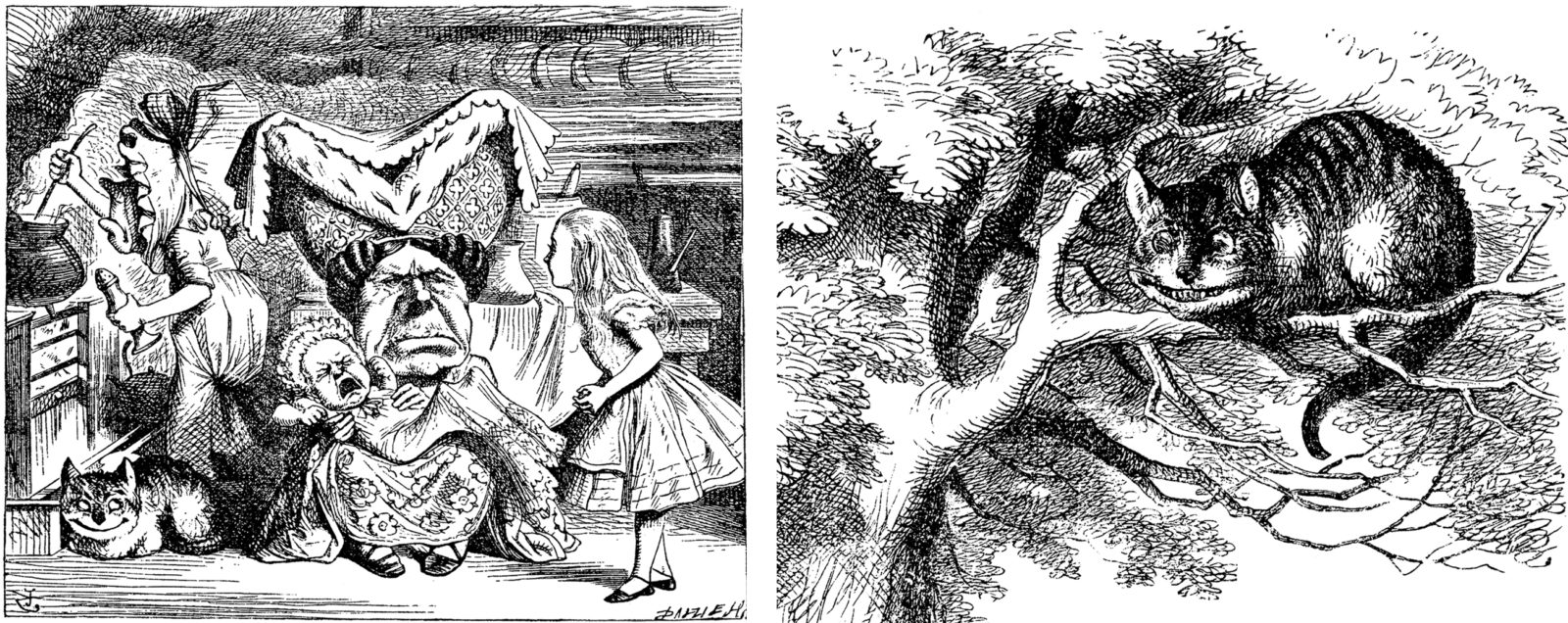

Lewis Carroll was the pen name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898). Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is his most famous work and the drawings created for it are among the most memorable children’s book illustrations of all time. Dodgson outlined his story on a rowing trip in 1862, eventually committing it to paper by 1864. It was published in 1865, with illustrations by Sir John Tenniel (1820-1914), a British illustrator and political cartoonist. Tenniel was selected on the strength of his work for the satirical Punch Magazine. Tenniel worked for Punch for fifty years, yet he is most well known for his Alice illustrations.

The image above shows the Cheshire Cat as originally drawn by Tenniel for publication in 1865. The images were adjusted for a later adaptation of the story, The Nursery Alice, published in 1890 as a shortened version of the full Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and in which Tenniel’s original drawings were enlarged and colorized.

The whole story is set in a dream that little Alice has one summer’s day. However the symbolism written into it by Dodgson is cause for much debate and a number of theories have arisen as to its meaning, ranging from psychoanalytical interpretations pertaining to sex, through to elaborate ideas that parody the mathematics of the day. What is known for sure is that Dodgson included a lot of personal jokes within the text, had great fun with language, and created some of the weirdest but most endearing characters!

The predominant literary and artistic movement going into the first part of the Victorian era was Romanticism, officially until 1850. The Romantics placed emphasis on the idea that individual subjectivity and the resulting emotional responses, especially extreme ones, could break free of the rationalism imposed by the Enlightenment and could be used as a source of aesthetic experience. They concerned themselves with the pursuit of the sublime and the belief that truth and beauty sustain each other. In the quest for sublimity, it was natural to turn to nature, and to landscapes. The painting above by Peter Graham (1836-1921) dates from 1878, yet it perfectly encapsulates romantic ideals. Atmospheric and brooding, Graham’s landscape is rich with intense emotional response to the mood of his surroundings. Loose brushwork and a powerful focus on light reflect the painter’s appreciation of the sublime found in the landscape of Scotland. The grandeur and purity of nature as described by Graham is indisputable.

William Powell Frith (1819–1909), on the other hand, liked to depict every day Victorian life. He was fond of panoramic scenes full of bustle and activity – my favorite being The Railway Station, 1862. This is the kind of painting that is almost cartoonish – more like something that was destined to be an illustration in a periodical, or a snapshot of a scene from a nineteenth-century novel. Every character is involved in some kind of interaction, from picking up hat boxes and kissing their children, to tending their dogs and showing their tickets. Every face has a different expression: concerned, surprised, nonchalant, distracted, even imploring. The station itself is rendered more like a line drawing that recedes into the distance which helps to center our attention on the people. Frith pays attention to the details, especially the clothing: the palette he uses is quite muted, but we can see furs, silks, velvet, fringed wool shawls, and a wide variety of hats among other things. Travelers have dropped items on the floor and baggage has been left unattended while the station employees load luggage on to the train. It’s a wonderful scene showing a moment in daily Victorian life.

Frith wasn’t only busy depicting his fellow Victorians, he was also busy creating them! By his first wife, Isabelle, he managed to bring no less than twelve children into the world whilst at the same time supporting a mistress, Mary, who lived only a mile away and with whom he produced a further seven children. A busy man indeed, and hardly the epitome of British Victorian morality and middle-class respectability that was deemed so important at the time. He did eventually do the right thing: when Isabelle died in 1880 he made an honest woman of Mary by marrying her. Very proper!

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was conceived in c.1848 by artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais. The group, heavily influenced by Romanticism, was known for its interest in revived medievalism, clearly expressed especially in the later paintings of Rossetti. Their use of line, a bright color palette, and attention to detail harked back to fifteenth-century Italian and Flemish art, perhaps also mimicking the illuminated manuscripts of the Medieval period. The group grew and became highly influential, however, it is Rossetti who is perhaps its most well-known member. After 1856 it was he who continued the more medieval aspects of the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic.

In October 1857 Rossetti met Jane Burden, later to become Jane Morris. He asked her to model for the group, who were at the time engaged in the production of murals depicting Arthurian legend. By 1859 Jane had married William Morris, a textile designer and poet, but her relationship with Rossetti as his model and muse continued until Rossetti’s death in 1882.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood helped to usher in the new Aesthetic movement in the later Victorian era, with which the phrase ‘art for art’s sake’ is associated. They believed that the appreciation of beauty could be an end in itself, thus they rejected utilitarianism which claimed that all art should have a moral point. Another major exponent of this movement was the writer Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), who believed in the idea that art should be beautiful before it is anything else, and should not be fashioned around social or moral influences. He believed in the autonomy of art and its freedom from the constraints of proselytizing.

As an additional, quirky bit of information, Lewis Carroll and Rossetti knew each other. Carroll even photographed Rossetti and his family in the garden at their house in Cheyne Walk, 1863!

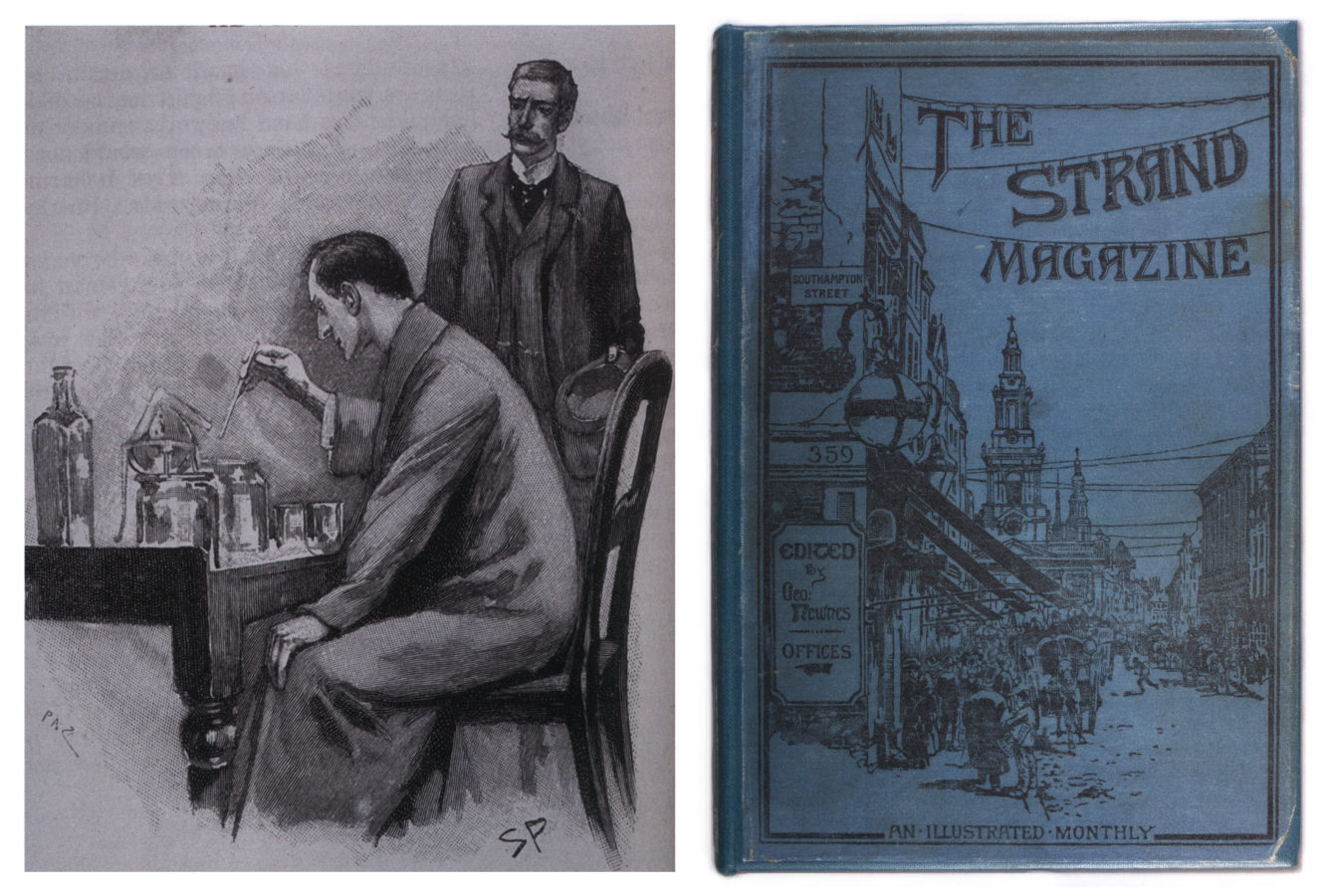

The most famous literary detective of all time? If you are British, you certainly know who Sherlock Holmes is to the extent that you might even believe him to have been a historical figure rather than a fictional character. If you are not British you probably still know who Sherlock Holmes is! The Sherlock Holmes stories were created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930) and were serialized in The Strand Magazine with illustrations by Sidney Edward Paget (1860-1908).

Paget’s drawings of 211b Baker Street (the fictional home of Holmes and Watson) depicted ideal Victorian domestic life at its most cozy and enchanting, fulfilling contemporary ideas that a safe, comfortable and righteous home was at the heart of Victorian life. The Baker Street setting, accurately reconstructed in the photograph above, would have been familiar to the readership of Doyle’s stories who may have owned many similar household furnishings and items themselves. This familiarity was a kind of shield against the potential violence and disorder of the world beyond the domestic interior and importantly provided an essential foundation for stories such as the Sign of Four (1890) which went far beyond the average Victorian’s comfort zone in terms of the unfamiliar. The concept of ‘home’ represented refuge and safety, protection from physical, emotional, or moral harm – values that were also embedded in the characters of Holmes and Watson. Paget’s illustrations helped to anchor these characters and their solid, reliable principles firmly in the minds of Victorian readers.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!