Between Word and Image: The Creative Mind of David Jones

David Jones (1895–1974) was an artist, poet, writer and craftsman; a name synonymous with the Modernist era but one that still remains lesser known...

Guest Profile 21 October 2024

18 June 2021 min Read

Zhang Daqian is considered the foremost Chinese artist in the last 500 years. If this is true, then what is it that makes Zhang Daqian so important? This short introduction can only sketch a brief outline of the artist’s life and achievements. Its purpose is to give an insight into his time, the places he’s been, and his staggering legacy that’s only beginning to be cataloged. There’s a lot to say. There’s no biography in English. But the facts we know show us someone of superabundant creative energy, charismatic personality, and unlimited talent to draw and paint anything he sees.

His life begins auspiciously. Shortly before he was born in 1899, his mother dreamt an elderly man presented her with an immense shining bronze basin saying, ‘This is for you.‘ The tiny figure inside looked at her quietly. The man said, Take care of him. There are three things he doesn’t like: the moon, meat, and fishy-smelling food. When he was born, meat repulsed him, and he always cried if he looked at the moon. And he didn’t eat fish. This story makes the little Zhang sound like someone destined to be different, a mysterious baby with greatness attached to him even before he’s born.

With his mother’s encouragement, he starts painting at age 9. She teaches him to love art, draw and paint. His older brother, similarly a successful artist, who paints lions, plays a crucial role in establishing his brother Zhang in the art world. They travel to Japan in 1919, where Zhang attends a college and learns about dying in the textile trade. He wanted to satisfy his family and become a businessman. But after two years, he decides to become a professional artist instead, and he moves to Shanghai.

An important side to his personality surfaces in 1919; he impetuously cloisters himself at a monastery outside Shanghai to avoid an arranged marriage after his girlfriend dies. His time there, where he practices his art quietly while he deliberates his future, would be repeated in other monasteries near Chengdu, where he stayed from 1938-1940 than in 1941-1943. His religious nature led him to practice Taoism too. He spends time in a famous Taoist temple, in the mountains, near Chengdu called Shangqing Gong and lives there intermittently from 1943 to 1948. He found the atmosphere delightful and painted nature scenes, birds, and animals.

Part of learning to be an artist in China is copying the great masters. Zhang Daqian is so talented at this he discovers he can reproduce them perfectly. He also learns that connoisseurs who view his reproductions believe they’d identified the real thing. One connoisseur is so convinced he’s getting the original that he won’t let Zhang say no to his request to purchase the copy. Zhang relates this incident in his own words and describes how it happened.

Huang Pin-huang was visiting Mr. Tseng and quite by chance he saw my painting. He was enraptured with it, and like most avid collectors he wanted to possess it. He enquired of Mr. Tseng the name of its owner. Somehow Mr. Tseng did not make the situation clear and Huang was so blinded with the charm of that painting that he had never conceived the possibility that it might have been done by anyone else than Shih T’ao. He at once said he wanted to buy the picture. Whereupon, Mr. Tseng told me to go and see Mr. Huang. I need hardly say I felt highly satisfied with my effort and I determined to make the most of the circumstances. I asked Mr. Huang why he was so particularly struck by the painting. With an air of condescension, perhaps quite appropriate to his age, he pronounced the verdict: ‘This authentic Shih T’ao is a rare piece of art but only the discerning can tell. How much should I offer to induce you to part with it?’ Half jokingly, I said: ‘I should be quite happy to swap it with the one that I wanted to borrow from you.’ Who would have thought the deal would be concluded there and then?

Three Contemporary Chinese Painters, T.C. Lai, University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1975.

The masterpiece is a copy of Shih Tao, a traditional style that shows how meticulous the artist had to paint to perfectly copy it.

Zhang’s perfect reproductions bring in over ten million dollars during his lifetime. Many prominent national galleries own them, some without knowing if they are authentic or a copy.

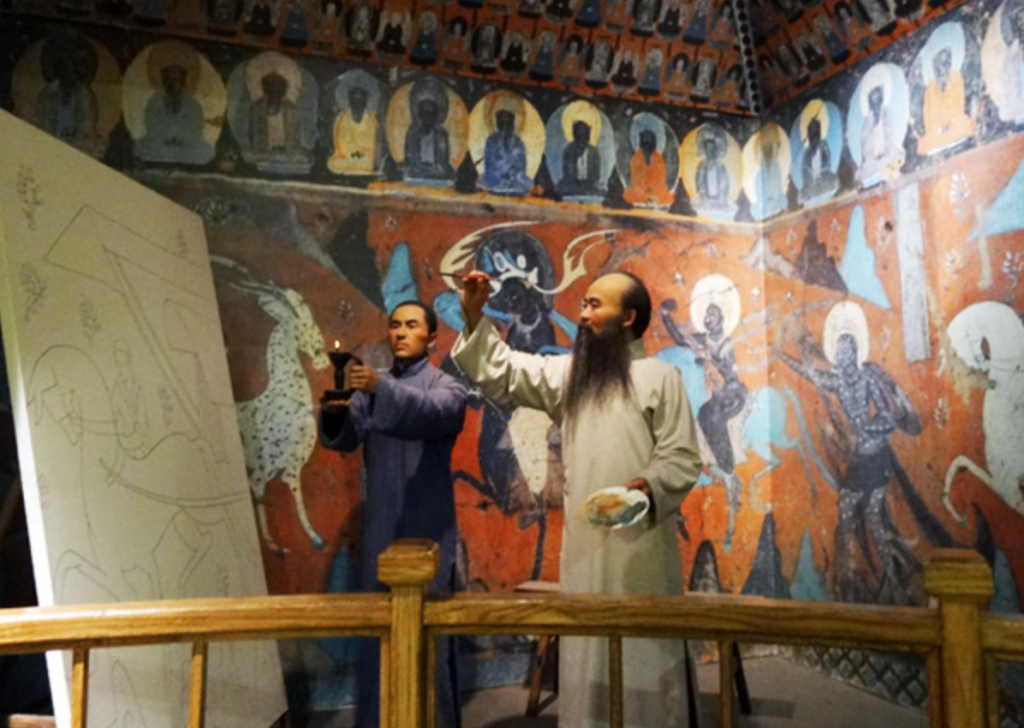

After years of traveling widely in China – practicing calligraphy, ink-brush painting, exhibiting, and collecting paintings of great Chinese masters he admired – in 1936, he’s asked to be a professor at the National Central University, Nanking. Here, he soon finds an outlet for his adventurous spirit. Zhang Daqian, and a group of artists, go on an excursion to Dunhuang in northern China and start a long project copying the religious cave paintings there were deteriorating after hundreds of years of neglect. The project lasted for almost three years. The experience changes his life not only as a painter but also in a spiritual sense when he discovers his roots in these evocative scenes of religious devotion.

After this, Zhang Daqian paints the lotus blossom in a myriad of ways. The lotus is symbolic of the purity of body, speech, and mind. It’s rooted in mud; its flower blossoms crown the long stalks as if floating above the muddy waters of attachment and desire. It’s a central symbol of Buddhist detachment in the quest for enlightenment.

Another quest in Zhang’s life that takes him away from China for the next 30 years begins when he flees his country during the great political changes taking place during this period. In 1948, he goes to Hong Kong, then Japan, then in 1950, to India, where he has several exhibitions. The works he completes in Darjeeling mark the zenith of his mastery of traditional fine brushwork, or gongbi technique. Riding in the Autumn Countryside is a good example. The central white-robed figure is finely drawn, riding a black stallion along a hill with finely drawn sparse brown landscape forms in the background with calligraphy down the right side. He paints many women in this style too.

In 1952, ever restless for new experiences, he sells an expensive painting and continues his exile. Zhang Daqian can now afford to take his family to South America, where he rents an estate twelve miles outside Mendoza, Argentina.

He describes his home and family in a poem:

I am quite pleased with my abode, so far removed,

Where tall pines and willows give flitting shades,

Where green hills are so pictogenic,

And the sound of waterfalls is music enough.

Sometimes visitors call, and wine is ready;

Sometimes a flower or two decorate my wife’s hair;

Recently, my children have been keeping themselves busy

With reading and the composition of verses.

Zhang Daqian’s poem in Three Contemporary Chinese Painters, T.C. Lai, University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1975.

This idyllic life in Argentina changes a year later for another location just as beautiful, in Brazil, where he builds a house and develops the gardens, ponds, and pavilions in the Chinese style. He stays here until 1971.

It’s been estimated that Zhang Daqian painted 500 paintings a year. He exhibited them in Europe and other parts of the world, where he traveled regularly. In the 1960’s he travels to Carmel, California, a mecca for artists on the west coast of the US. Some of his friends live there. He likes the scenery, especially the pine and cypress trees, so in 1971 he moves from Brazil to a new residence at Pebble Beach, near Carmel, California.

From the 1960’s he begins to paint in a new style called splash-ink painting. It has expressionistic and impressionistic qualities that create the essence of a dreamscape of predominantly blue and black colors. This painting style is very well received, and the famous auction house Christie’s has sold them for vast sums to eager buyers.

At the end of his life, he becomes homesick. He, therefore, returns to Taipei and builds a residence near the Palace Museum. This residence is a museum now. He died there in 1983, and his ashes are interred under an enormous rock he brought back from California.

Zhang Daqian’s legacy is enormous. He painted 30,000 paintings of spectacular quality and in many styles. He’s a modern legend in China, and recently he’s been recognized in the West. His work has generated extensive interest in the way he’s added western-style Expressionism and Impressionism to traditional-style Chinese subjects. This new style gives him great notoriety as a brilliant innovator.

His reputation is still being established. Only five percent of his paintings have been cataloged. Exhibits are shown in prestigious galleries in China and around the world. His paintings have brought in more at auction than Picasso’s works. His status is tarnished by his brilliant forgeries, but his other work shows his greatness as an original artist of the first order. He’s a tremendous giant, a lion among painters, an astonishing artist that only comes along once in 500 years!

Johnson, Mark. Chang Dai-chien: A California Reintroduction. San Francisco State University, 1999.

Lai, T.C. Three Contemporary Chinese Painters. Univ. of Washington Press, Seattle, 1975.

Menton, Sara Lindsay. Authenticity and the Copy: Analyzing Western Connoisseurship of Chinese Painting Through the Work of Zhang Daqian. Univ. of Oregon, 2014.

Shen C.Y. Fu. Challenging the Past: The Paintings of Chang Dai-chien. Washington, D.C., 1991.

Sullivan, Michael. Modern Chinese Artists: a biographical dictionary. Univ. of California Press, Berkeley, 2006.

Splash Art Painting Surges in Value, Shanghai Daily, Monday, October 21, 2013.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!