In the catalogue for a 1959 exhibition on Precisionist art at the Walker Art Centre in Minneapolis, Director Martin Friedman said of the precisionist artists that they were not so much innovators or theorists as they were synthesizers.

In many ways, this was a true statement. Well-known artists, such as Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth, filtered the influences of Cubism and Purism following their visits to Paris in the 1920s, in order to create something quite special in terms of American Art.

However, for three lesser-known artists, the fact they were either born abroad or lived there seemed to bring a wider range of influences to bear with their artwork.

Gerald Murphy, George Ault, and Louis Lozowick were all working at a time when artists were embracing modernity in all its forms and using it to create an image of what America really stood for. The time of the ‘Realists’ was over, and precision and distillation were the key concepts in art.

American Synthesizers #1: Gerald Murphy, 1888-1964

Gerald Murphy was born in Boston in 1888 to a wealthy family and the expectations that he would go to the best schools and move into the family business. Murphy was not willing to play that game, and his idea of fun was not in selling leather made goods.

In 1921, Murphy and his wife, Sara moved to Paris to escape all the family quarrels and expectations and it was where he took up painting and acquaintances who today read as a who’s who of 1920 art and literature: old friend, Cole Porter, Scott F Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda, Fernand Leger, Ernest Hemingway, Jean Cocteau, John Dos Passos, Pablo Picasso, to name just a few. It was not long before the couple moved to the Cap d’Antibes in the South of France where they became the centre of an incredible social circle.

For just seven years, Murphy painted. His works were not realist, views from his windows or from the beach, as had been the custom of artists who travelled to his area. Murphy’s clean lines, bold colour palette and use of consumer culture would preempt Pop Art by decades.

Razor, 1924

In this 1924 work, Murphy has taken three ‘masculine’ items; a razor, fountain pen and safety matches, and a very bold typographical stance to produce a most unusual still life. Taking his inspiration from the manly tasks of grooming, business, and smoking, it would be assumed that Murphy was validating this stance, however, Murphy was, despite being married, homosexual and he found this difficult to hide. He sadly classed this as his ‘defect’ and his artworks do seem to include aspects of his hidden part of his life, as we shall in a painting that appeared a year later: Watch.

Watch, 1925

This exquisite piece is a modernist example of the way in which technology was being viewed as a thing of aesthetic beauty. The canvas includes two watches that had significant personal meaning to Murphy, being a Railroad watch designed by Murphy’s father’s company and the gold watch given to him as an engagement present by Sara. It is currently on display at De Young Museum in San Francisco as part of their Cult of the Machine exhibition.

The catalogue for the exhibition makes mention that experts have examined the cogs, wheels, and levers all depicted with a high level of accuracy. However, the mainspring is broken and would mean that this object would, in all reality, be nonfunctional. Scholars believe that this act of sabotage to what should be a working model is a metaphor for Murphy’s conflict about his ‘defect’. In a letter, Murphy expressed his fear that his life had been a process of concealment of the personal realities… The effect on my heart has been evident. It is now a faulty ‘instrument de precision’

Despite this area of unhappiness for Murphy, a family was important to him, and motifs representing his father, wife and children can be found in most of his works, but especially in one of the last paintings of his short-lived career.

Cocktail, 1927

The 20s in the United States included the Prohibition era and the rise of speakeasies and illegal liquor-fuelled the new Jazz Age. The imagery of Cocktail, while on the surface reflects the hedonistic social life in Paris and in Cap d’Antibes, Murphy included references to himself, wife and three children in the five cigars; the cover of the box showing a sailing ship, an occupation Murphy enjoyed enormously.

Using the influences of his friends, Picasso, Braque and Leger, Murphy synthesizes cubist style in his depiction of the inner and outer segments of the lemon, as well as the cocktail glass.

Sadly, the Murphy’s return to the United States brought an end to his artistic endeavours when he took on the mantle of President of Mark Cross.

American Synthesizers #2: Louis Lozowick 1892-1973

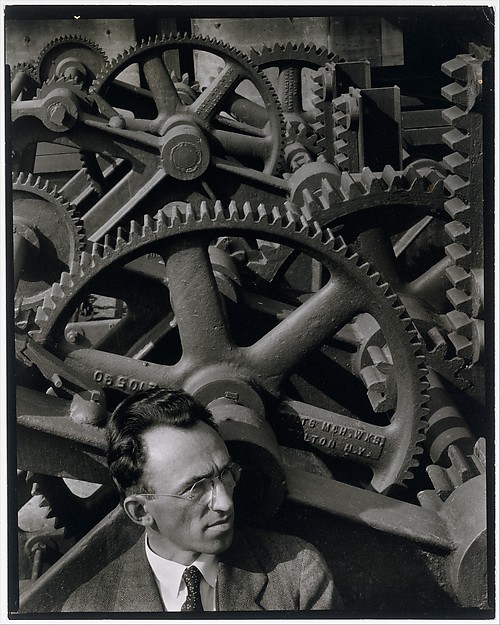

The staged photography by Ralph Steiner links Louis Lozowick strongly to the machine age, marrying the geometric composition to the way in which Lozowick saw the industrial age in his new home of America.

In the catalogue for the 1927 Machine Age Exposition at 119 West 57th Street, New York, Lozowick included an essay entitled, The Americanization of Art. In it, Lozowick gave what can be described as a manifesto for the artists of this time in which he said:

The artist’s task is to sift and sort the material at hand, mold it to his purpose by separating the plastically essential from the adventitious and, in this manner, enrich the existing culture and help to establish a new tradition.

Louis Lozowick came to the United States in 1906 from Ukraine and studied at the National Academy of Design in New York, and at Ohio State University. He travelled extensively through Europe in the 1920s and his artwork synthesized the ideas he came across when he met the likes of El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich.

Pittsburgh, 1922-23

In his essay, Lozowick urged artists to depict The skyscrapers of New York, the grain elevators of Minneapolis, the steel mills of Pittsburgh, the oil wells of Oklahoma. In this landscape of Pittsburgh, Lozowick used the layering techniques he had seen on his travels to create this claustrophobic portrayal of Pittsburgh within a narrow vertical plane. The chimneys battle with the buildings for space. The colour palette is restricted here and there is a resonance with the work being done by Kazimir Malevich in Russia at this time, as we can see in Red Circle.

Red Circle, 1924

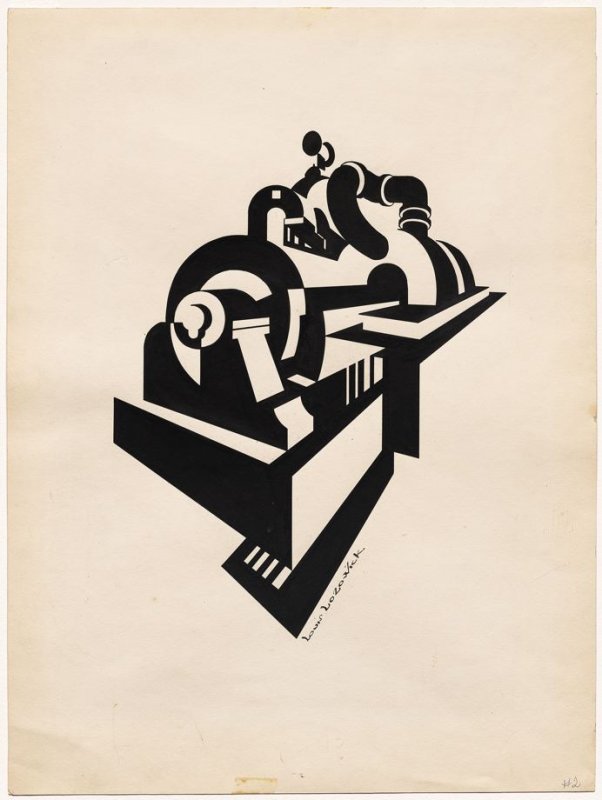

Lozowick was greatly influenced by Russian Suprematism, the notion that you could reduce the world to geometric forms and use of a limited colour palette, where the red dominates as no other colour can. Lozowick was clearly in tune with the changing landscape and his manifesto for precisionism can be seen in his work in ink.

This brush and ink work epitomises Lovowick’s belief that:

a composition is most effective when its elements are used in a double function: associative, establishing contact with concrete objects of the real world and aesthetic; serving to create plastic values.

On the surface, a turbine machine is hardly glorious and beautiful. But, under Lovowick’s direction, the abstraction leaves us with sleek lines, and sensuous curves to reveal the beauty within the industrial landscapes that were supplanting the rural idylls that had come before.

American Synthesizers #3: George Ault

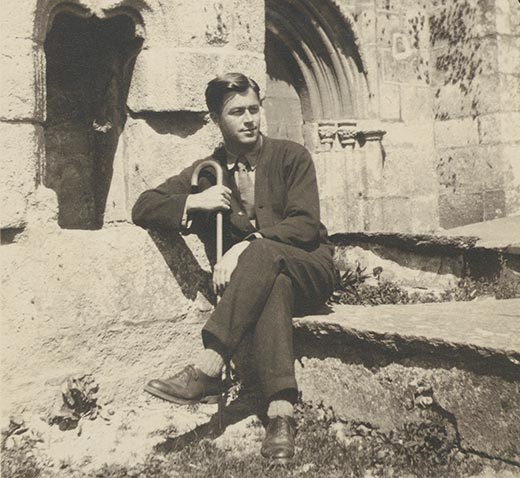

The life of George Ault (1891-1948) was ultimately a tragic one but his paintings have a detached, unemotional beauty about them that is perhaps unexpected.

Although born in Cleveland, Ault moved to London in order to study art at both the Slade School and St John’s Wood. He returned to the US and where his family lost their fortune in the Wall Street Crash and, following his mother’s death in a mental institution, Ault turned to alcohol as a way of coping. The loss of all three of his brothers to suicide added to the torment.

Ault’s career was surprisingly not as successful despite his early works being well received. He moved away from the centre of New York with this second wife to Woodstock, NY where, in 1948, Ault too, committed suicide in the Sawkill Brook during a storm.

In tribute to his work, his widow said, Ault’s art was an attempt to make “order out of chaos”.

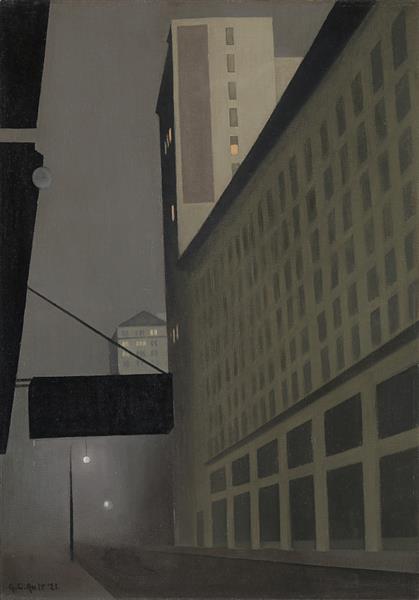

New York Night No. 2, 1921

These examples are perfectly ordered and, while Ault seemed to sit on the edge of precisionism through his geometric compositions, his use of atmosphere brings him more in line with realism. The way in which he uses the light of the nighttime is particularly stunning. The misty light in New York Night Number 2 creates an eerie scene, devoid of human interaction.

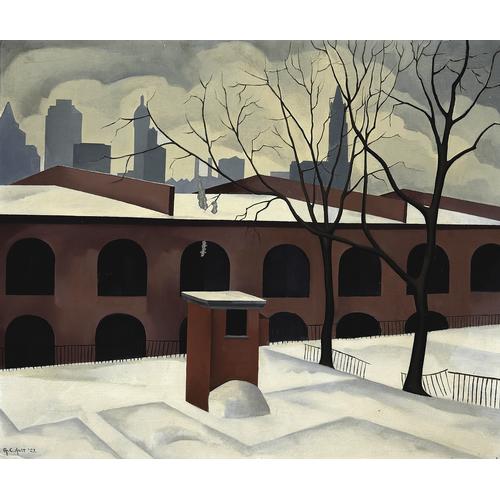

View from Brooklyn, 1927

In ‘View from Brooklyn’, the dark, empty windows reflect nothing of the crisp, wintery scene that dominates the foreground. No footsteps in the snow; the place abandoned, fences broken. Nothing enters and nothing leaves this scene. It is quite literally frozen in time.

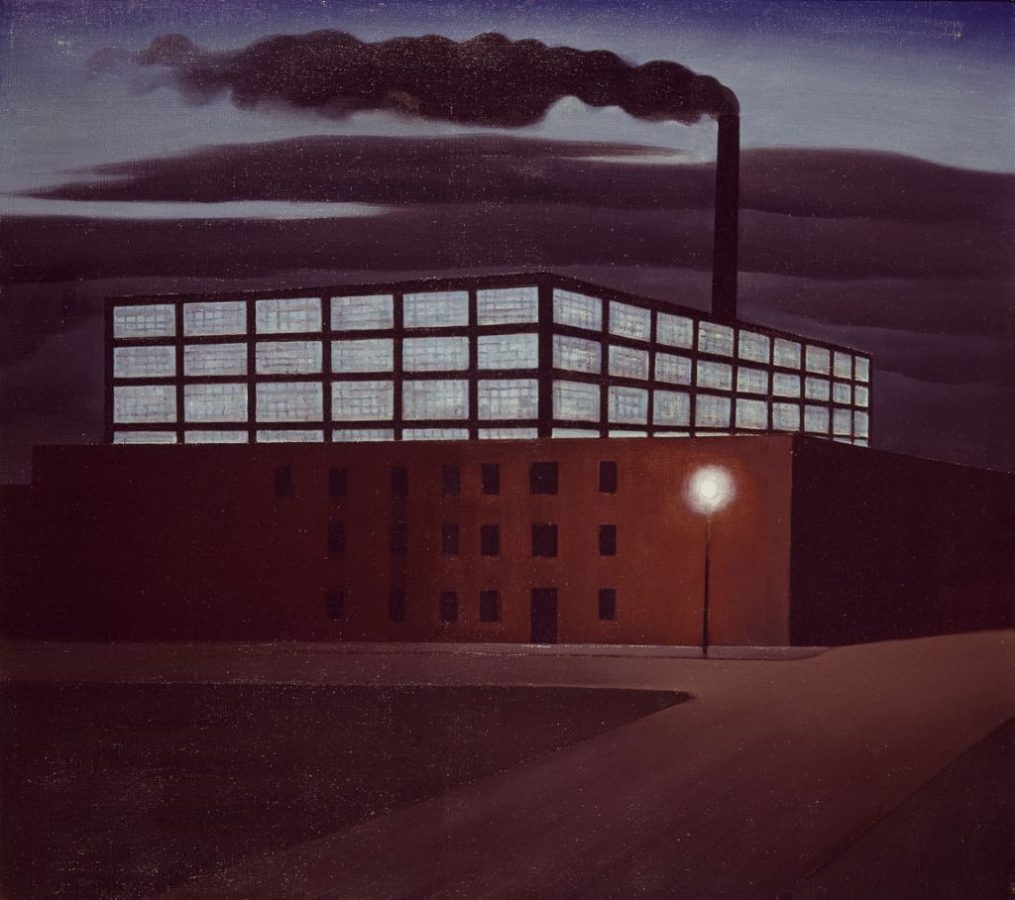

Hoboken Factory, 1932

This painting of a factory also combines the precisionist view of industry – the smoke billowing from the chimney stack and the windows glowing with the electric lights. But look at little closer and there are no shadows of the workers within the factory. The automated machines seem to have taken control of the building. Alienation and the lack of human contact appealed to Ault; understandably so, given his personal circumstances.

All three of our artists influenced by their travels, their experiences and synthesizing features from realism, cubism, abstraction, were able create works that, in the words of Louis Lovowick:

in this manner the flowing rhythm of Modern America may be gripped and stayed and its synthesis eloquently rendered in the native idiom.

Find out more:

Current exhibitions:

- de Young Museum, Cult of the Machine, March 24–August 12, 2018

- Ashmolean Museum, America’s Cool Modernism, 23 March – 22 July 2018

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0300234023″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/61GoBFckguL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”139″]

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”B01K0QISZW” locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/41IFdaW72VL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”124″]