The Downfall of the Mighty Lydian King Candaules in Art

Suppose you are not satisfied with any of the historical or fantasy dramas out there lately where all kinds of slander, deception, and politicking...

Erol Degirmenci 2 March 2023

Luo Ping, Freud’s godfather, proclaimed: “Kill or be killed…” But of course, Luo Ping was subtler than this; he only suggests what was in his “unconscious” mind.

Sigmund Freud uncovered our powerful unconscious instincts about life and death; love and hate; sex and survival. Luo Ping felt his way towards these human instincts and desires from another direction – a Buddhist’s reflections on death, desire, reincarnation, ghosts, sorrow, and connections to our deeper selves.

Luo Ping was an extraordinary man who saw within himself. Just like one of the symbolists of the 19th century or modernists in the 20th century. He was an 18th-century Chinese painter who depicted the “unconscious” and was indeed a very unusual artist.

In his book called, Record of My Beliefs, Luo Ping revealed much information about what he learned over his life as an artist, including descriptions of the cosmology of this world: heaven and hell, demons, ghosts, goblins, and other ghoulish entities. He also described transmigration, the rare blessing of being born in a human body, the similar roots of Confucian and Buddhist belief, and the importance of Chan Buddhist masters in the lives of Song-dynasty Confucians. He devoted many pages to specific Buddhist tenets, such as karmic supererogation, right conduct, confession, and practices stemming from a number of different traditions such as the contemplation of phrases in Chan riddles, the use of esoteric phrases without clear meaning, and Pure Land-style repetition of the Buddha’s name.

He lived during the heady days when Yangzhou was a center of culture and learning in the middle of the 18th century. This was where he started his journey as one of the most interesting Chinese artists of his time.

Unfortunately, Luo Ping had a rough start and was orphaned when he was only a year old. Many years later in 1775, aged 42, he described how he still felt about this experience.

He that was born on the day of man,

Is a pitiable creature.

Standing at the foot of the Golden Ox Mountain tears rolled down my face.

Back and forth, for three thousand miles from south to north I hasten.

For twenty years I have seen my parents’ grave in my dreams.

Who knows that, when not even a year old, I lost my father?

I sigh, harboring lifelong sorrow.

In this life I can only envy those who may delight and honor their parents.

In a life to come, so I hope, I am destined to remain at their side.

Luo Ping’s poem, from K. Karlsson, Luo Ping: The Life, Career, and Art of an Eighteenth-century Chinese Painter, 2004.

Bereavement for Luo Ping was a never-ending heartache. His early social identity seems to have been derived from his accomplishments as a poet, which caught the attention of the literati in Yangzhou, the city where he lived, married and started a family. He soon found a mentor, Jin Nong, and turned to painting traditional literati subjects in his own unique style.

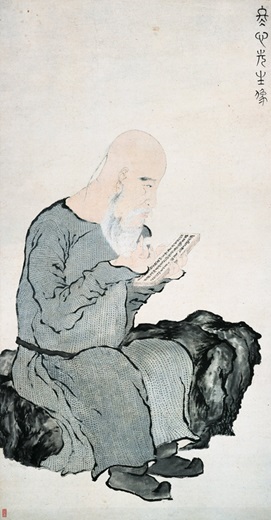

These two men, one 70 years old and the other in his twenties, were both itinerant Buddhists and felt that they were karmically connected. Jin called himself “the Youngest Buddhist Monk” and Luo Ping called himself “the Monk of the Temple of Flowers”. This mystical union found its way into several portraits of Jin by his protégé. One of the most striking, called Portrait of Mr. Dongxin, is of Jin as a luohan.

Luohan are protectors of the dharma, disciples of Buddha, ageless adepts who refuse nirvana to stay in the world and embody the virtues of the Three Harmonies, a combination of Taoism, Buddhism and Confucianism.

In Luo’s Portrait of Mr. Dongxin, his master Jin Nong is shown in the disguise of a luohan called Nandimitra. His bald dome clearly identifies him as he contemplates a Himalayan-style text. He twists the thin hairs of his beard and clearly represents the posture and importance of the sage protectors who cloistered themselves in small cottages hidden away in remote mountains.

This portrait shows Jin Nong as someone both of this world and another distant one. These overlaps in Luo Ping’s portraiture allow us an insight into the double life of his master, blurring the lines between the seen and unseen. Luo Ping also believed himself to be the reincarnation of another luohan, a Buddhist monk of the Temple of Flowers, which he said was revealed to him in a dream. He gave much importance to what he saw in dreams, images that straddle the conscious and the unconscious.

One of Luo Ping’s most famous paintings called Ghost Amusement brings us into the dream world via a series of eight different-sized panels showing ghost-like creatures such as imps being chased by a fat-head with short arms and claw-like hands; worried-looking ghosts with eyes staring at subtle terrors we can only imagine; a tall, emaciated ghost looking lost with thin twisted lips and vacant eyes, long green arms and legs disappearing into a murky cloud nearly covering him from head to foot. These paintings are joined together in a long scroll. Luo Ping painted them to illustrate the ghost stories which were in vogue at the time. He described them in a poem he wrote suggesting he didn’t just imagine them but saw them as clearly as he could see real people.

A dim autumn room with but a single lamp;

From the bookcase a famished rat falls to the ground.

Presumptuous ghosts, as though no else were there,

Come sniggering in groups of three or four.

It’s not only my discerning eyesight surely

That perversely makes me see this ‘ghostly realm.’

Some have necks twisted and tall;

Some have bodies humpbacked and squat.

Some expose teeth like melon seeds.

Some have fingers large as thighs;

The whole yard grows danker as the wind picks up

and rushes headlong to the far porches.

Stealthily I follow the hidden traces;

the falling leaves patter down like rain.

I turn back, feeling terror arise,

Hairs stand on end upon my chilled gooseflesh.

So I sigh for that non-believer Ruan Zhan

Who in the end was insulted by a ghost.

Whether you choose ‘to listen in a frivolous way’ is up to you:

What I am saying is not frivolous.

Luo Ping, Gathering on an Autumn’s Night in the Studio of Huang Shoushi Telling Ghost Stories, 1760.

The Ghost Amusement Scroll set Luo Ping’s fame and made him instantly identifiable wherever he went, and it was painted after Jin Nong’s death. When business turned for the worse in Yangzhou, Luo Ping decided to use his reputation and make a new start in Beijing, where business was flourishing and creative talents were collected from around the world. Luo Ping’s fame, after painting his Ghost Amusement Scroll, quickly established him with many important intellectuals and sophisticated members of high society there.

This began his back-and-forth sojourns from Beijing to Yangzhou for the next two decades. He established himself in Beijing while living and working near his beloved family in Yangzhou, with side trips to other places. While in Beijing in 1779, he learned that his beloved wife had died, at age 47 which left him heartbroken. After arranging the funeral, he composed a poem to express his sorrow for being unable to return and be with her at the time of her death.

Your death voids any principle of life;

My departure was [to be followed] by my return.

I wanted to return, but I could not;

Had I returned, you would not have known.

Luo Ping’s poem, in K. Karlsson, Luo Ping: The Life, Career, and Art of an Eighteenth-century Chinese Painter, 2004.

His wife, Fang Wangyi, whom he married when was 19, was from an illustrious, cultured family in Yangzhou. She painted and wrote poems, both of which made her well-known there. Her loss caused Luo Ping deep bereavement until the end of his life. After she died, he slowly turned inward, away from the world, and, in his last years, he lived in a monastery as a pauper, with nothing but her memories, lost in a world of ghosts from the past.

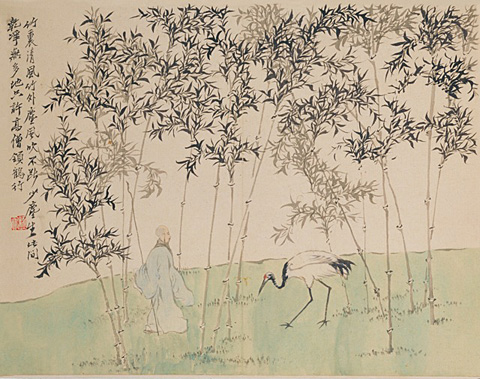

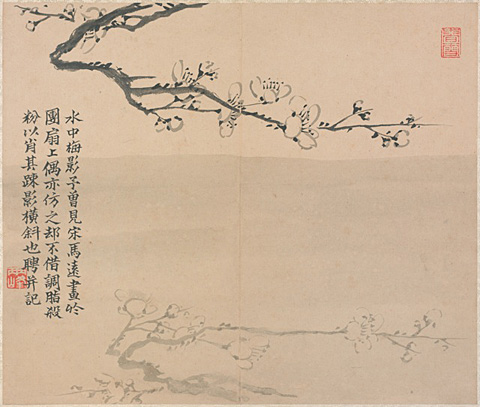

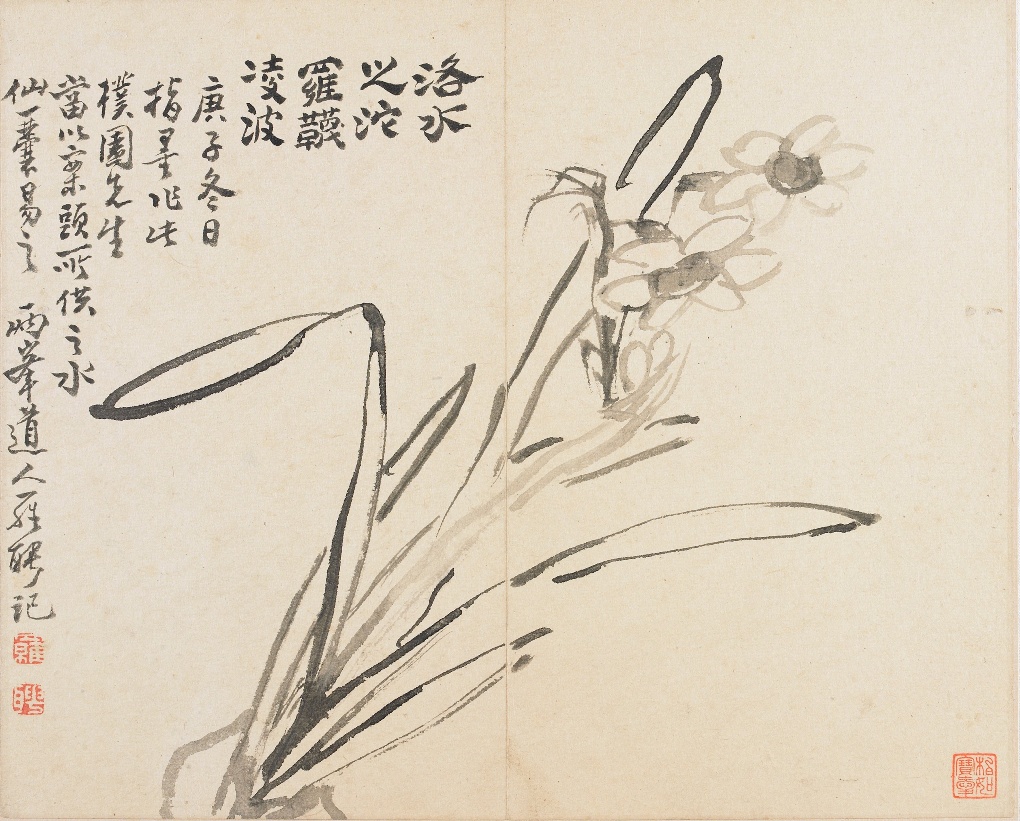

Fang Wangyi gave him three children who also become artists. The family became known as the Luo Family Plum School due to their genre paintings of plum blossoms at their family studio in Yangzhou.

On his first sojourn to Beijing, Luo focused on tradition-bound landscapes and plum paintings, very similar to Jin Nong’s genre style. ‘Looking at Luo was just like seeing Jin come back to life.’ His painting, called In Search of Plum Blossoms, shows the delicate brush strokes he mastered over the years while working with his beloved master Jin Nong.

After many busy years of painting and working with intellectuals in both cities, Luo Ping settled in Beijing for the last eight years of his life. He stayed in close contact with his son, who operated the family studio in Yangzhou. His reputation in Beijing was that of a famous painter with side occupations as a specialized copyist and art expert. In 1789, ten years after his wife’s death, he accepted a position as the director of an orphanage, which reminded him of the loss of his own parents and stirred up memories of their loss.

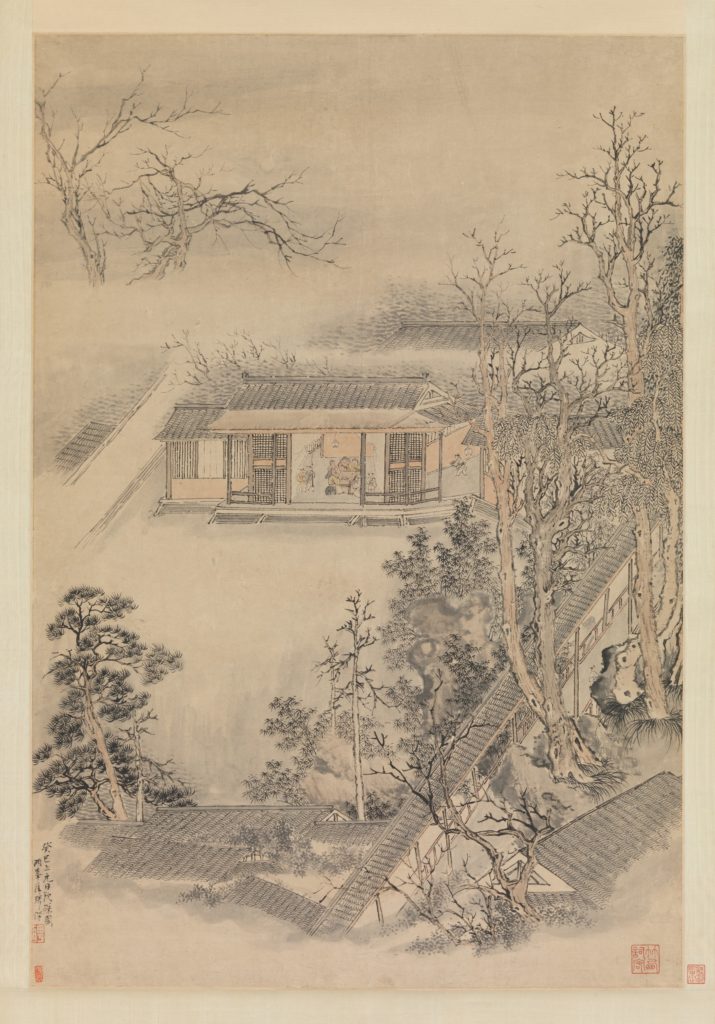

During this time, his paintings began to show more and more individuality. He signaled the emergence of a new kind of artist, who counted on his own ability, using his ‘10 fingers’ to make visible the imagery of his own mind. His late paintings, Su Shi and the Two Miao or The Sleeping Monk depict this kind of personal take on the world around him. The subjects are ambiguous, the thinly layered washes present a crystalline atmosphere.

In his final years, he slowly withdrew into a personal world of private memories and visionary encounters. Ghostly apparitions became so frequent that they now haunt him in broad daylight. After completing his treatise, Record of My Beliefs, in 1791 Luo began living an ascetic life regulated by daily rituals and few outings. When his poet friend, Wu Xiqi, visited Luo in 1798, at a shrine off Liulichang Street, he found the artist sitting on a rush mat worshipping Maitreya. His borrowed clothes were worn out and painting commissions were rare. Luo’s son – Luo Yunzuan, visited him there and brought him back to Yangzhou where, on the third day of the seventh month of the following year, Luo passed away.

His remains are interred on the outskirts of Yangzhou. His funeral was attended by thousands of people who revered this giant of individualistic painting. Two artists who knew and loved him painted a portrait of the old man sitting in a monastery, holding an amulet and lost in his own world. A moving tribute is added to this last portrait of Luo Ping:

Formally accepted student of Jin Nong;

Chan monk in the Temple of Flowers in a previous life;

A completely original painter of Buddhist figures,

Daoist immortals, the marvelous, and the able;

One who, never muddled, painted with a limpid lucidity,

Who could rarely be persuaded to look at paintings, frequenting poets as a fellow poet.

Before reaching old age, he withered away and died.

Each time I go to Yangzhou, my tears flow all the more.

A tribute to Luo Ping, in K. Karlsson, Luo Ping: The Life, Career, and Art of an Eighteenth-century Chinese Painter, 2004.

Luo Ping left a great legacy for other individualistic artists who followed him. He accomplished something rarely seen in Chinese art by representing images he conceived straight out of his experience with ghosts, reincarnated luohan, dreams, sorrow, and heartbreak.

His paintings range from landscapes, plum blossoms, portraits, buildings, and animals to imaginary creatures from the netherworld, Buddhist luohan, Daoist immortals, the marvelous, and the plain.

All his paintings leave the viewer with a sense of wonder, mystery, and thankfulness that such a painter existed. One who was able to bridge the gap between the conscious and unconscious, defining a new kind of person in a new kind of reality.

Kim Karlsson, Luo Ping: The Life, Career, and Art of an Eighteenth-century Chinese Painter, 2004.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!