The 80s: Photographing Britain

The 80s: Photographing Britain at Tate Britain in London is a kaleidoscopic chronicle of more-or-less a decade, where photography witnessed and...

Ania Kaczynska 25 November 2024

What’s your favorite color? Why? Have you ever tried getting to know someone better by asking this question? It can fill an awkward silence in a conversation, and to some, it can reveal personality traits that allow them to learn more about their interlocutor. The answer is often simple, spontaneous, of a certain obviousness, and echoes one’s subconscious as much as the collective unconscious. But what about color in art? What if one of the colors could become an obsession crossing the barriers of reason, creating links, and telling a story of some of the most traumatic—as well as most peaceful—moments of a lifetime. Here is the story of colors in Pablo Picasso’s work.

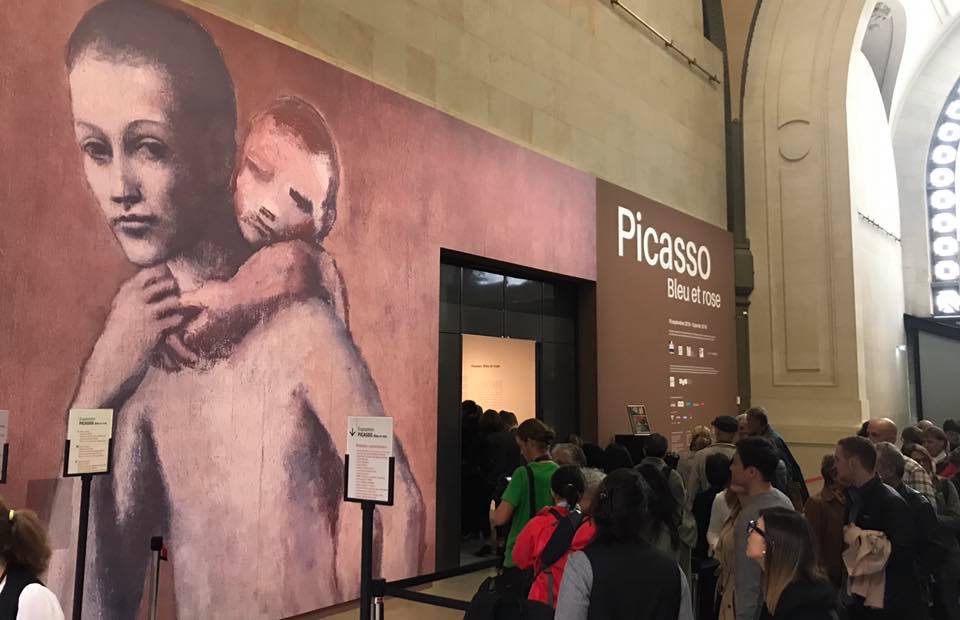

The answer to this question is the central point of a 2018 exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, entitled Picasso. Blue and Rose (18 September 2018–6 January 2019). The museum, once a train station, saw in 1900 the beginning of a Parisian adventure for the young Pablo Ruiz, a young man whom you probably know better by the name of Pablo Picasso.

It is here that 300 of his pieces, including some of his major works, have been brought together retracing two periods of his life, known as the Blue and the Pink.

He was 18 years old, and after a promising start to his career in Spain, Picasso was invited to Paris to represent his country at the Exposition Universelle with a work that has been since lost. The invitation was an honor and an opportunity that he could not refuse—not only because of his career but also because he wanted to free himself from his father pushing him into a different artistic direction.

He and his friend Carlos Casagemas, who was also an artist, settled in the famous district of Pigalle, an ideal place for artists dreaming of taking part in the Bohemian fantasy life that was so popular at the beginning of the 20th century. The two friends were inseparable and enjoyed the exhilarating Parisian lifestyle, whether during the day or in the embraces of the nights.

Casagemas quickly fell in love with a young woman, Germaine, but sadly for him, this one-sided affection became an obsession and the passion drove him into a fatal fate. At the time, Picasso was working and traveling between France and Spain, and although he was aware of his friend’s depression and tried to help him, he had no idea of the tragedy that was about to take place on February 17, 1901.

Casagemas hosted a dinner party with his friends and Germaine at a restaurant called L’Hippodrome at 128 Boulevard de Clichy. At the end of the evening, he rose, gave a short speech, and then suddenly drew out a gun and fired at Germaine. He missed his target, but not realizing that, he turned the weapon on himself and put it to his right temple, pulling the trigger.

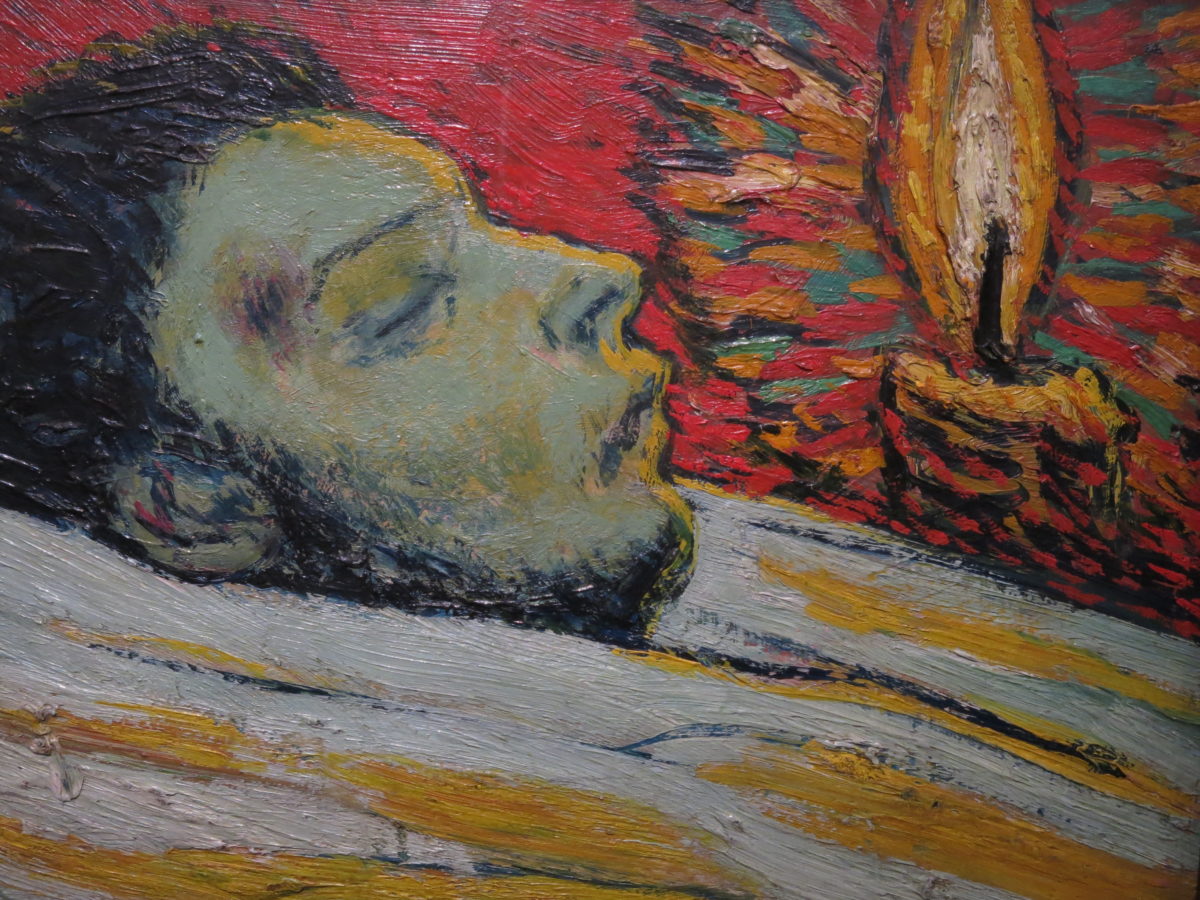

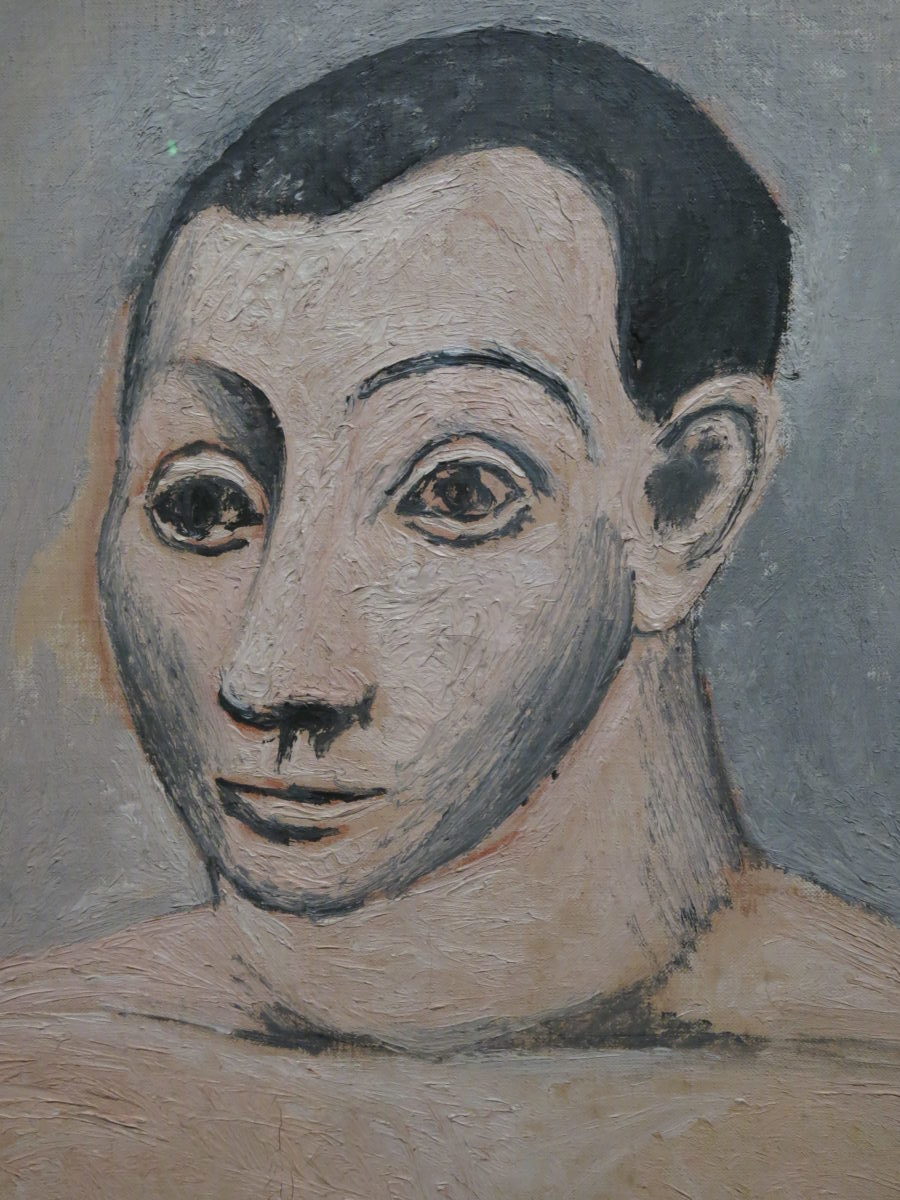

Picasso learned the terrible news and returned to Paris in March to suffer a long period of depression. A portrait illustrates its starting point: The Death of Casagemas, 1901, is the start of the blue period: Three long years of mourning and working through his pain to finally achieve his own catharsis—a descent into the dark, almost blue-black depths of human nature.

There are two distinct worlds in this portrait. One is the world of the living—red and orange, illustrated by the oil lamp trying to bring life to a man’s face that might be at last serene. The other—blue, green, and yellow— reflects nothing more than the cold absence of life, a profile in the shadow, created by a fatal bullet.

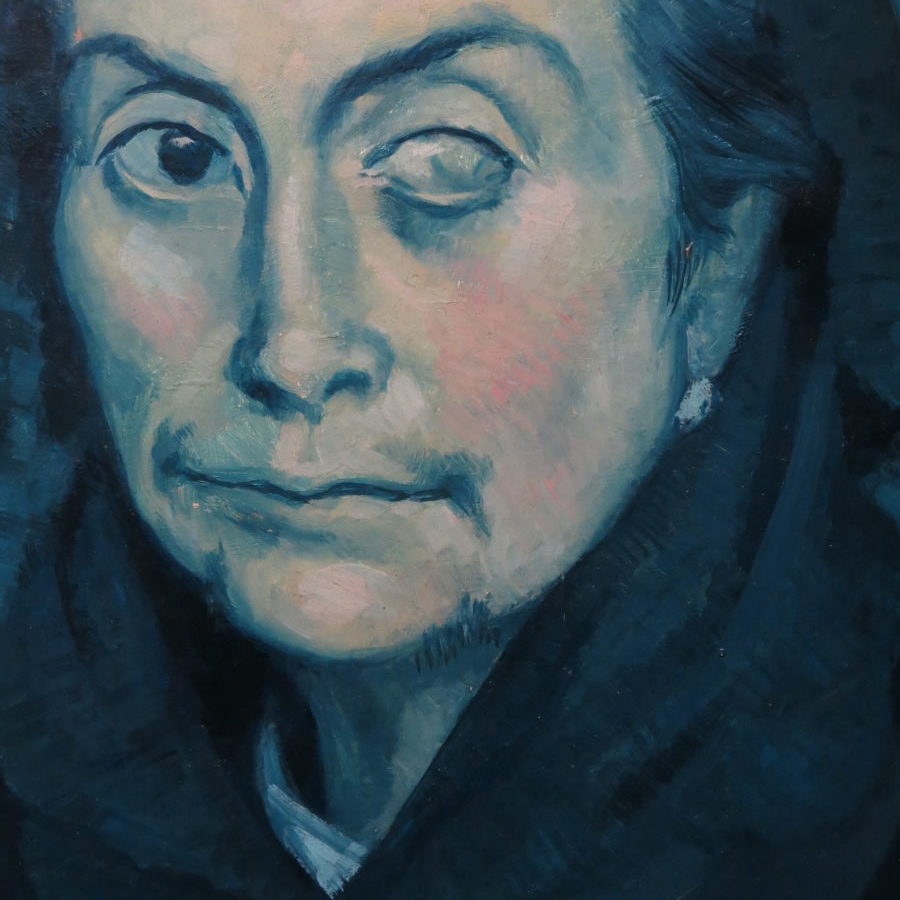

At the exhibition, I stroll in the alleys of these long years between the blues of the canvases and the blacks of Picasso’s drawings, which were totally unknown to me before. Bodies are slimmed down, attitudes filled with a certain piety reminding me of religious icons that should only be really observed by candlelight.

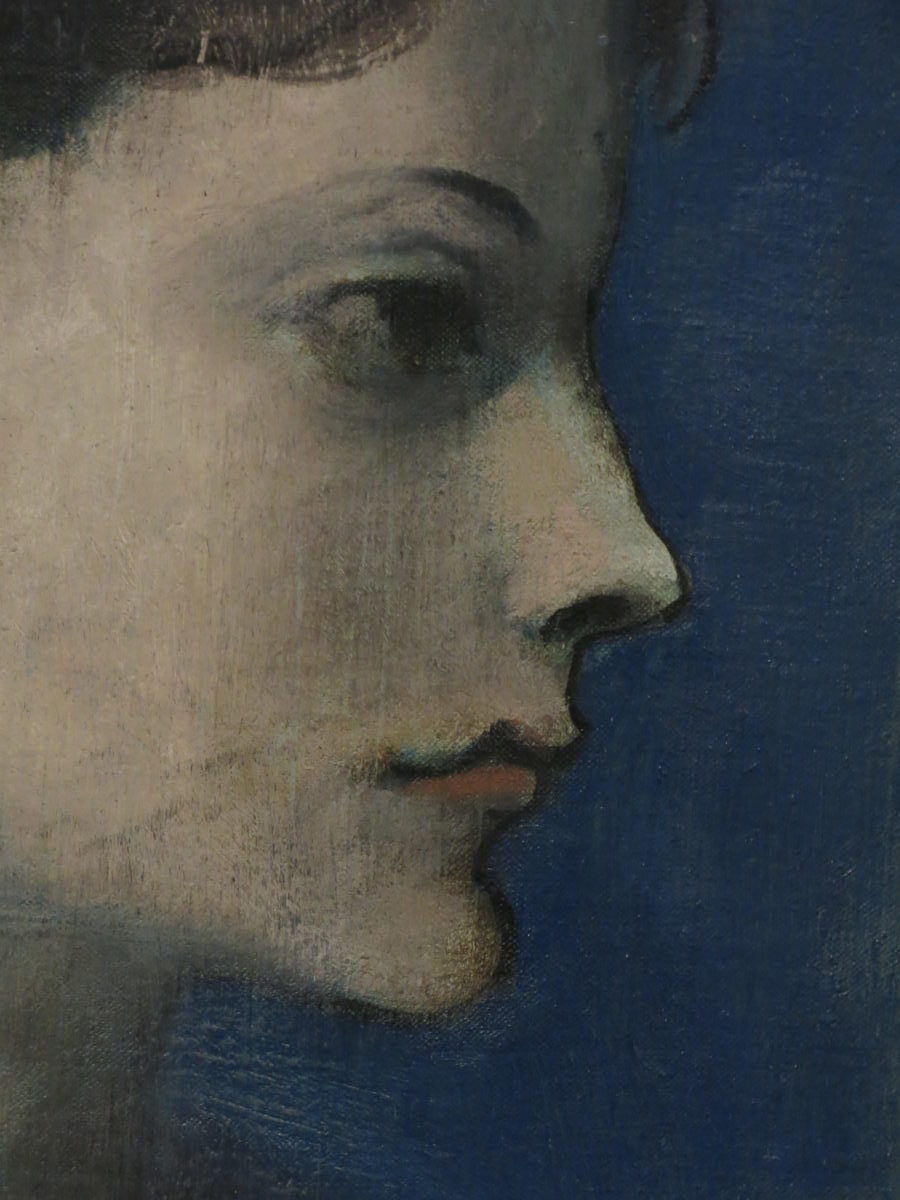

At a turning point, almost out of breath, I see in the distance a changing tone. I quickly move forward, impatiently passing canvases of major importance, and I stop suddenly. Indeed, the shades of blue are no longer the only element in Picasso’s work, and other tints of color are creating a new harmony. I approach the portrait of a woman, which draws my attention. The woman is presented in profile with a direct and powerful look. She is beautiful and full of new strength, her name is Madeleine. I came a little closer – her lips are pink.

Indeed, the color of her skin proves that life begins to reappear in Picasso’s art, especially during one of his trips to a circus, where he met his love in the person of Madeleine.

This exhibition continues to take on life and color, and Expressionism eventually meets Cubism, but I decide it is time for me to conclude and propose an answer to my first question.

What does it all tell us about colors? Does color define us? Do colors allow us to express a depth of emotions that cannot be reduced to “simple” words? Much has been said about Pablo Picasso and those periods. Carl Jung once talked about schizophrenia, historians create links between Vincent Van Gogh’s troubled nights, Edvard Munch’s intimate love life, and Giotto’s starry skies.

For me, there is evidence, a lesson, or perhaps a piece of advice, left to us by Picasso in his color from more than a century ago. The ability of color to express emotion. Regardless of the emotional depth they can reach and the madness they can inspire, they are perhaps the key to the liberation of the soul and a necessary catharsis to move forward. And Picasso’s works do move forward, acting as a testimony to his personal experience and, on a greater scale, the experience of human nature.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!