Charles White was a prolific artist. The retrospective exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, which opened on October 7 and will be on display until January 2019, not only demonstrates this; it also makes me want to take out my bottle of India ink, dip my pen nib into it, and start drawing hundreds and thousands of cross-hatched lines, just the way White drew them.

Flicking the wrist and drawing some parallel lines in one direction and then drawing another set of parallel lines in another direction that intersect the first set of lines creates tones with texture, especially when the lines are thin. The individual lines become subordinate to the mass of lines in the same way the letters of a word become subordinate to the word itself.

Drawing all these lines in the context of modelling forms from dark to light is a long, time-consuming process, especially when compared to another approach—drawing or painting large masses of tone with a few strokes of the pencil or brush. This is why most pen and ink drawings that have this type of crosshatching are relatively small in size.

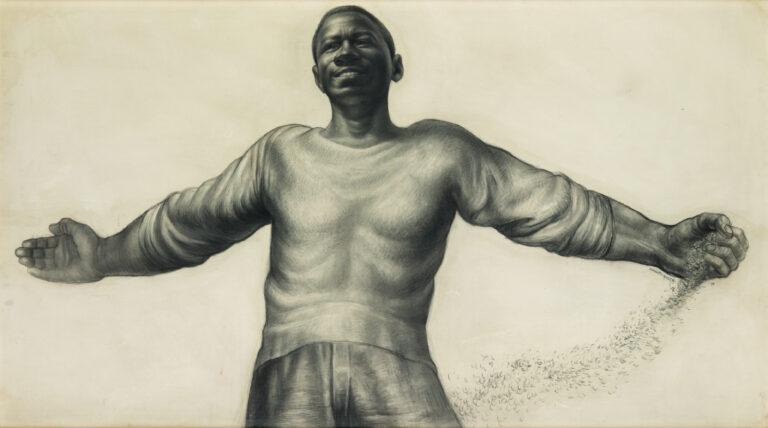

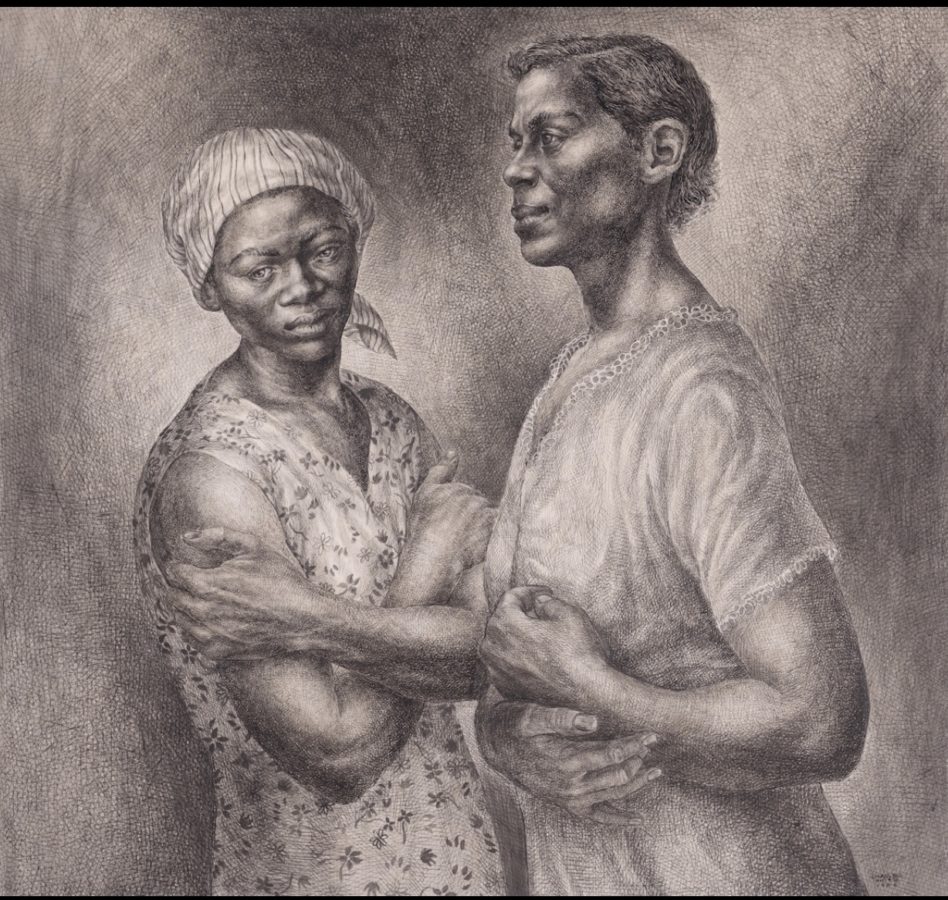

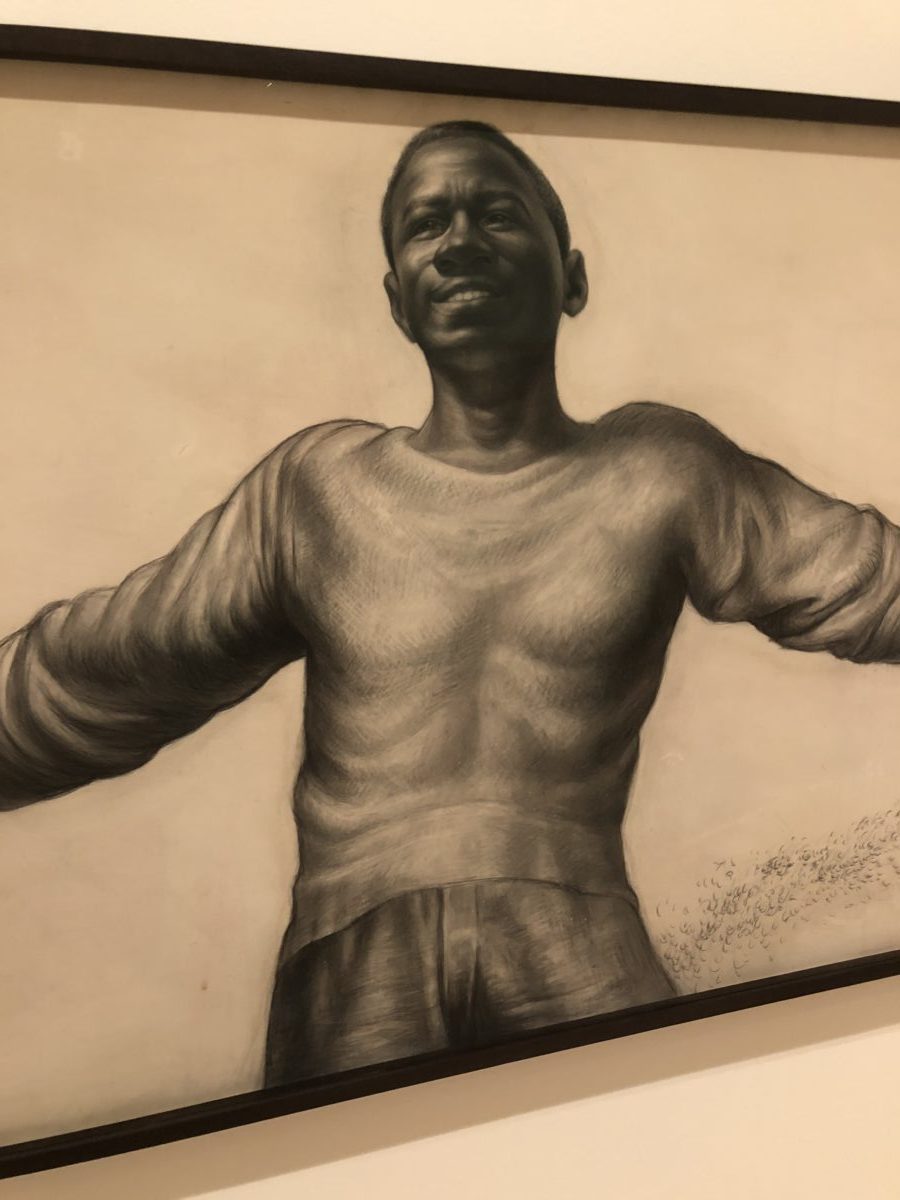

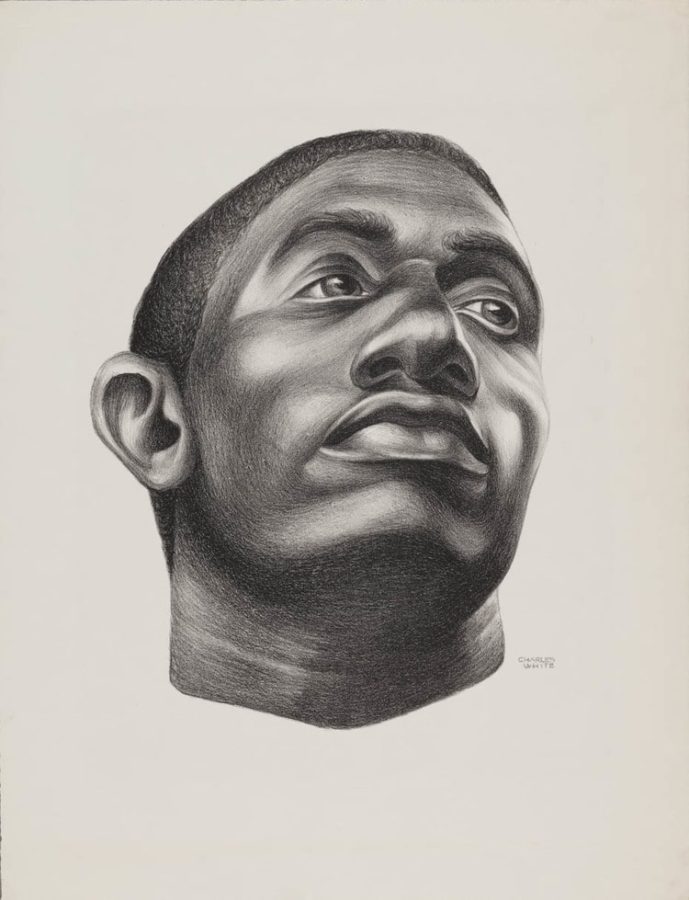

The drawings of Charles White are special for many reasons. One reason is that his drawings are large, yet many of them have intricate and delicate crosshatching throughout. I am in awe of the patience White must have had to be able to render form after form using this method on such a large surface.

The exhibition includes a video of Charles White. He is shown teaching a group of students, wanting his students to be passionate and to fight for what they believe in as artists. White believed that his art had to mean something, and he used his art to fight injustice by pointing out injustice in a provocative and thoughtful way.

In the video, White told his students that, as artists, two plus two does not necessarily have to equal four, that two plus two can equal three as well. I wondered what this idea meant for him, and because the video did not explore this theme after introducing it, I can only explore the answer through my own experience of the artist’s body of work.

White had many styles throughout his life. One of his earlier styles exemplifies what I think he was trying to convey to his students. In the 1930s and 1940s, White simplifies the planes of the figures he is painting and drawing. This simplification is especially noticeable in his treatment of hands. Each plane of the hand is exaggerated and stylized. His choices are based on reality, but he is not modelling forms and drawing lines based solely on observation.

The lines by the knuckles are examples of this. White is drawing his simplified idea of the lines of the knuckle, not the observed knuckle. What is fascinating to me about White’s simplifications is that the details of each form are not lost in the process. White has managed to simplify by a process of reorganization. This is what I think White means by two plus two not necessarily equaling four.

As artists, we can do anything. We can break any rule. We can explore any idea, and do so in a new way, in a creative way, both in terms of technique and in the meaning we are striving to express.

And in so doing, I want to stop everything and start drawing hands the way White draws them because there is so much to learn from his approach. White does the same thing with heads during this period. The eyes, the nose, and the mouth are all divided into simple geometric forms, each one peacefully coexisting with the others. From a distance, one may fail to notice that White is doing this. However, as one walks closer, one cannot help but notice.

In the 1950s, White models his forms more traditionally. His technique is so advanced that I am in awe of most of these works as I stand in front of them. The forms are effortlessly three dimensional. His artwork from this period runs counter to the abstract expressionist movement that flourished in New York City in the 1940s and 1950s. (White was living in New York City during most of this time.)

But then, in the 1960s, the paintings and drawings of Charles White became more abstract. The human figure, which had been the focus of attention up to this point, is now subordinate to a more abstract-looking whole that has not fully abandoned its figurative roots. The flexible arithmetic of Charles White is at play once more. He adds the abstract without removing the figurative forms that the abstract is supposed to be replacing.

The Museum of Modern Art describes the change in White’s art in the following manner:

In the last decade of his career, White charted new visual and technical terrain. This included developing a layered, multi-dimensional oil-wash drawing style, seen in his Wanted Poster Series from 1969-71. Modelled after posters seeking the recapture of enslaved people who had escaped, the drawings—which include stencilled letters, fragments of text, and images of women and children—link the trials of contemporary African Americans with those of their enslaved ancestors.

Charles White believed that:

An artist must bear a special responsibility. He must be accountable for the content of his work. And that work should reflect a deep, abiding concern for humanity. He has that responsibility whether he wants it or not because he’s dealing with ideas. And ideas are power. They must be used one way or the other.

I wrestled with these words when I read them. They are from an interview that was published in 1978, the year before White died. I wondered what the alternative would be. I wondered whether he would have felt the same way if he were alive today, fifty years after those words had been spoken. And I wondered whether that “special responsibility” superseded his desire to be an artist, so that, if he were, for whatever reason, not able to express those feelings in his work, would he have found another medium with which to express his ideas?

And then I realized that having “a deep, abiding concern for humanity” is a gift that too few of us truly possess. Even the best of the abstract artists are motivated by something more than aesthetics.

The art of Charles White, beyond his considerable technical skills, is fueled by the passions of the man who created it. I highly recommend this exhibition; this rich exploration of the artist is merely the starting point for understanding this often overlooked artist.