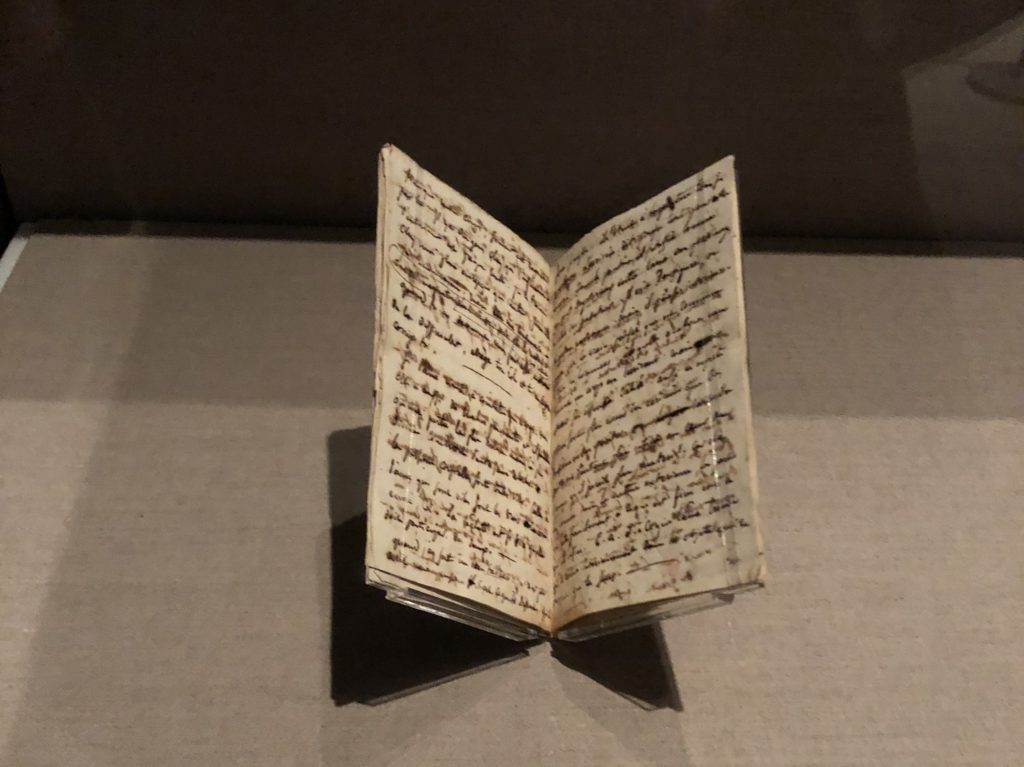

The rooms were dimly lit and majestic, and the paintings of Eugène Delacroix were larger than life. The Metropolitan Museum presented these paintings in this environment, on the heels of its exhibition of Delacroix’s drawings. That exhibition is more intimate because the sketchbooks of Delacroix were being displayed. An artist’s sketchbook is like a writer’s diary—a deeply personal exploration that is not made to be shared with others. The finished paintings in this exhibition are the result of the artist’s journey.

This exhibition of Delacroix’s paintings also includes excerpts from the journals of Delacroix. These journal entries are displayed to help the viewer understand the workings of the artist’s mind in a deeper way, but they are not the focal point of the exhibition itself. An example of the Met’s description of a journal entry is as follows:

This page features the first known formulation of what would become a credo for Delacroix—that painting is a bridge between artist and viewer, with material advantages over literature: ‘When I have done a fine painting, I have not expressed any thoughts. That’s what they say. How simple-minded they are!… A writer says almost everything in order to be understood; painting builds a kind of mysterious bridge between the soul of the characters and that of the spectator.

I often see an exhibition of an artist I admire and become so inspired, I want to rush home and paint and draw in the style of that artist, even if his or her vision is very different from mine. That was not my feeling here. In this environment, the paintings had an ‘other world’ quality about them, as if the hands that produced them were not those of a mortal man. I found myself standing in awe in front of each painting.

Delacroix was a Romantic artist, yet, if he had wanted to, he could have been a Neoclassicist, another Ingres. However, Delacroix was not willing to undergo a traditional classical education; he was not willing to draw and paint from plaster casts for five years. His goals were different. Throughout this exhibition, I enjoyed looking at the paintings up close, where the color and the brushstrokes and the painterly quality of the work were more evident. Up close, I could see texture.

Delacroix inspired many artists and may be thought of as the grandfather of modern art. In the introduction to this exhibition, Van Gogh is quoted as saying:

What I find so fine about Delacroix is precisely that he reveals the liveliness of things, and the expression and the movement, that he is utterly beyond the paint.

This is followed by an even more revealing quote from Cézanne:

You can find us all in...Delacroix.

Not all the paintings in this exhibition were large. There were many smaller paintings as well. One of my favorites was Mortally Wounded Brigand Quenches His Thirst, from 1825. The mood of the painting can be sensed from a distance as one can feel the sweeping movement of the paint as the water flows around the man whose beard rests against the ground, his lips trying to drink in the water beneath him. But when one walks closer to the painting, everything is magnified. The brushstrokes have a life of their own. The yellow vest, which meshes nicely with a similarly colored frame that surrounds it, shimmers and vibrates all the more. And suddenly, one can see similar brushstrokes and a similar vibrancy in the paintings of Van Gogh.

A Lady and Her Valet, from 1826-1829, looks modern and abstract, even though this is a figurative painting of a seductive woman who is stretching and reclining in her bed. Normally, the body or the face of the woman would be the center of attention. In this painting, however, the horizontal rectangle of the bed intersected by the vertical drapery near her legs and the swirling drapery to the right of the canvas is what one is drawn to. Even if one notices the woman first, my eyes move away to the other design elements described above. This is a modern composition, closer to Rothko that to Ingres.

One of the masterpieces of this exhibition is The Death of Sardanapalus, from 1845-1846. This painting is magnificent from a distance, with so many figures moving about that it is difficult to discern exactly what is happening. When one takes a closer look, as I did, I was mesmerized by the movement of the brushstrokes, the brilliance of the color, and the way Delacroix was able to execute this painting from almost a purely painterly perspective. Line is subordinate to color and mass. And I could feel the mysterious bridge that Delacroix wrote about.

This wonderful exhibition will be on view through January 6, 2019. The Devotion to Drawing exhibition of Delacroix drawings will be on view through November 12, 2019. I highly recommend seeing both.

You might be interested also in Mr.Bacchus’ review of the Delacroix exhibition at the Louvre.

Learn more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”1588396517″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/51mgEeihPgL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”95″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”1588396800″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/517PCMuWBlL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”99″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”0691182361″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/51ucOdFsFaL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”89″]