5 American Impressionists You Need to Know

Impressionism is an art movement that originated in France in the 19th century. Artists associated with this movement are known for their dream-like...

Ruxi Rusu 16 September 2024

Did you know that NASA has quite a unique art collection and that they used to commission artists to document their missions and projects? Let us take you on a fascinating trip through the American space missions, illustrated by some pieces from NASA’s Art Program.

I hope future generations will realize that we have not only scientists and engineers capable of shaping the destiny of our age but artists worthy to keep them company.

Hereward Lester Cooke, excerpt from the letter to artists, in Eyewitness to Space.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was established by Congress and President Dwight Eisenhower in 1958, a year after the Soviet launch of Sputnik-1. The first steps in extraterrestrial exploration, Space Race anxiety, dreams of stepping on the Moon… Space was the place, and simply the only thing anyone could talk about. Just four years later, in 1962, the NASA Art Program was established. How did it happen so early?

The idea of establishing an art program itself wasn’t that strange, given the long American tradition of official military art. Artists were part of military programs since 1917, with their mission to document historic moments in a more emotive way than the objective snapshot of a camera. And what could be a more historic moment than stepping outside the borders of our own planet?

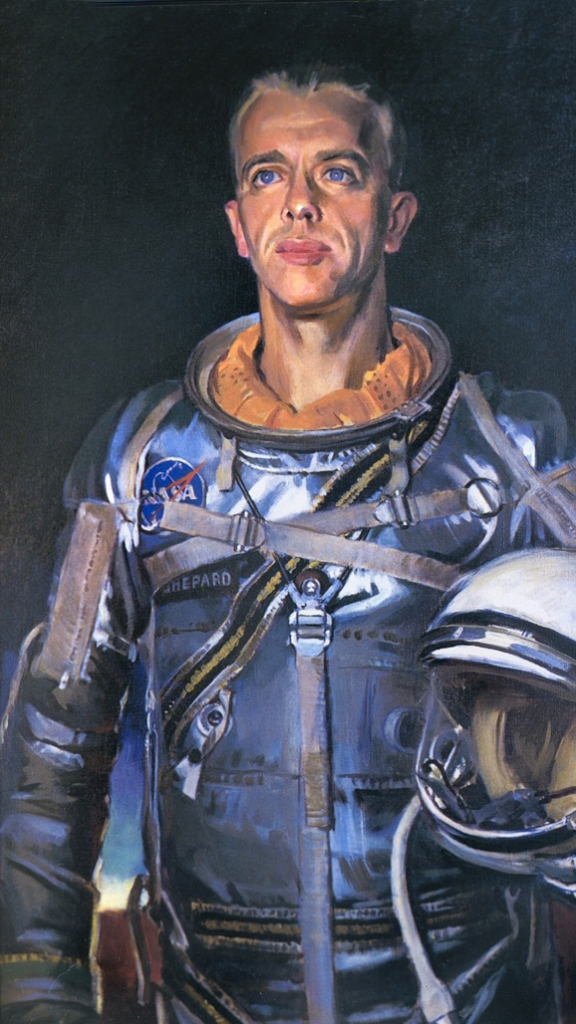

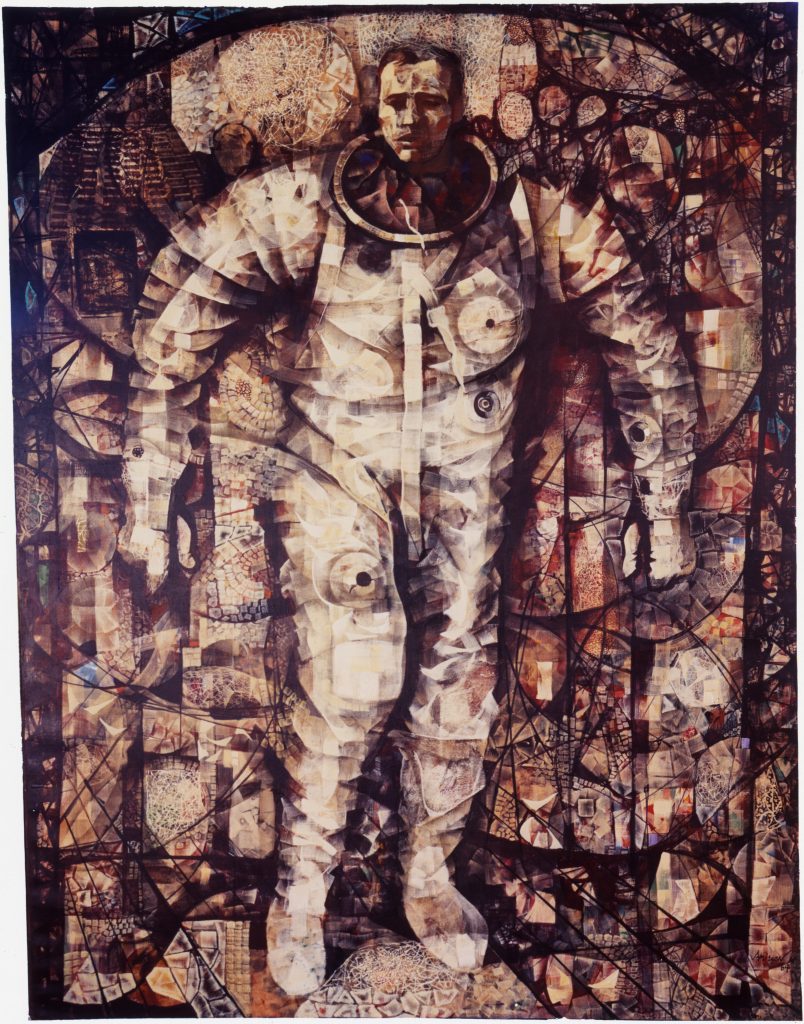

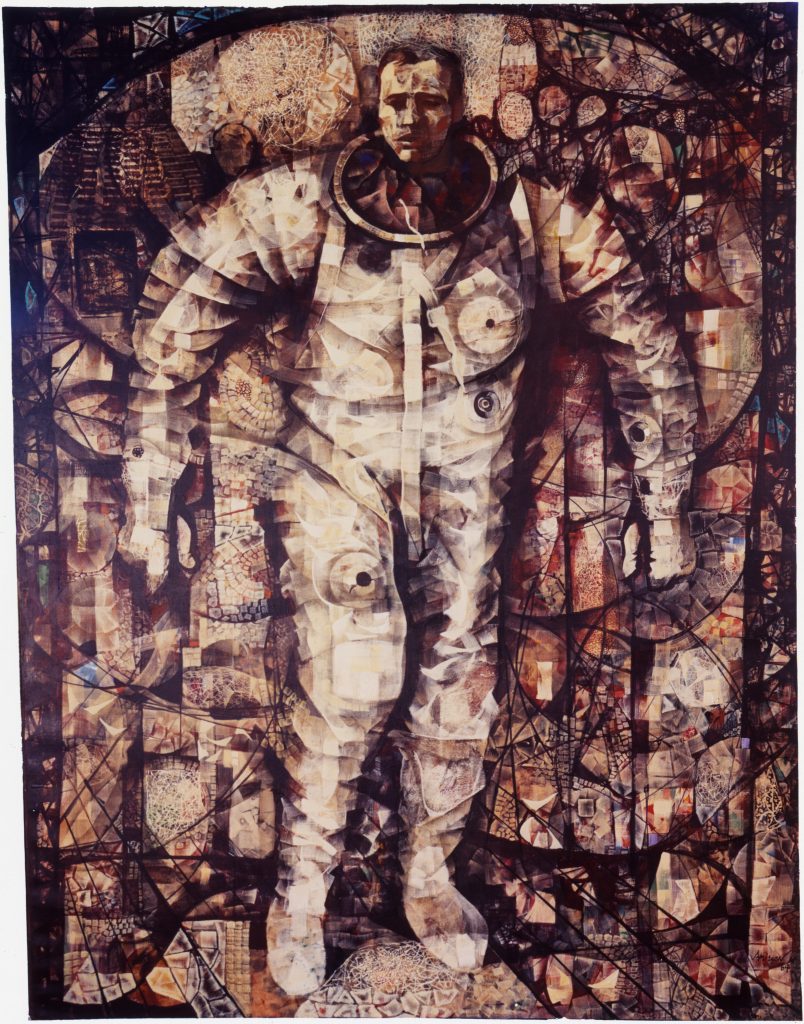

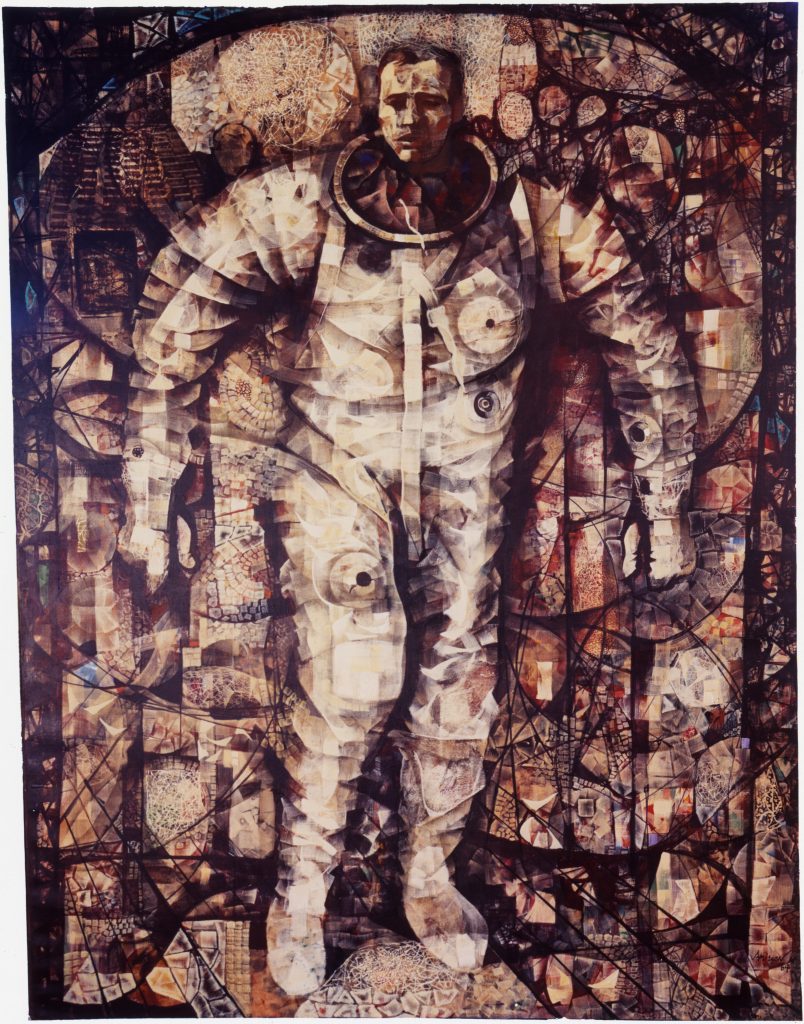

One of the first paintings under the NASA Art Program was Bruce Stevenson’s Portrait of Alan Shepard, the first American to travel into space. This piece was actually the spark behind the whole project – seeing this powerful depiction, James Webb (the agency’s administrator) ordered portraits of the rest of the crew.

James Webb shared his idea with John Walker, the director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, which agreed to support the project with his art historian insights. The program’s key points were to be written by NASA’s James Dean, an artist himself and a graduate of the Swain School of Design (currently part of the University of Massachusetts), and Hereward Lester Cooke, a curator from the National Gallery of Art.

Together they decided to select a group of American painters, giving them complete access to NASA’s mission grounds, the possibility to gain insight through conversations with the crew members, and complete freedom of artistic choices. The selected artists would get “all-appropriate security access”, which meant they could easily observe and depict the missions also from behind the scenes. Quoting Charles Schmidt, one of the program’s selected artists:

Nasa doesn’t tell you what to do or what to expect. They tell you where to go and what will be happening there, and why they think that particular activity is important. It’s up to you to supply the imagination and point of view.

Charles Schmidt, quoted in: Susan Lawson Bell, Artistry of Space the Nasa art program.

Even though the program’s key points stated full artistic freedom, the first group of painters was selected with careful precision. The choice is understandable – sticking with safe, liked, and well recognized American Realism guaranteed much-needed financial support from Congress. Most of the chosen artists were already experienced with military commissions.

The first lucky group was comprised of Peter Hurd, Lamar Dodd, John McCoy, George Weymouth, Paul Calle, Robert Shore, and Mitchell Jamieson. The group was later semi-formally joined by Norman Rockwell, which couldn’t be officially enlisted due to his previous engagements with Look magazine. The artists were picked by Hereward Lester Cooke from the Washington Gallery of Art, and all of them received a three-page letter mentioning a rather small payment of 800 dollars and the rules of further engagement. The artists were to archive every sketch and every piece of paper, the chosen medium had to be permanent and at least one of the artworks created during the mission was to be donated to NASA’s Art Collection.

Cooke’s letter is a piece of art by itself, and it perfectly shows the historical importance of everything that the artists were about to eyewitness.

(…) because the first steps in space exploration are going to make a hinge in the fate of mankind. Not since the lungfish slithered out of the Paleozoic slime have living creatures sought to change their environment, and not since Columbus have men dared to enter more dangerous and mysterious regions. Perhaps in space we will find greener pastures; perhaps we will find nothing but infinite hostility and we will return to realise that life on this planet is more precious than we ever imagined. Whatever the results, space exploration is changing history.

Hereward Lester Cooke, excerpt from the letter to artists, in Hereward Lester Cooke, Eyewitness to Space.

Cooke also mentioned the predominance of art above technological media such as photography or movies – “as the camera sees everything, yet understands nothing.”

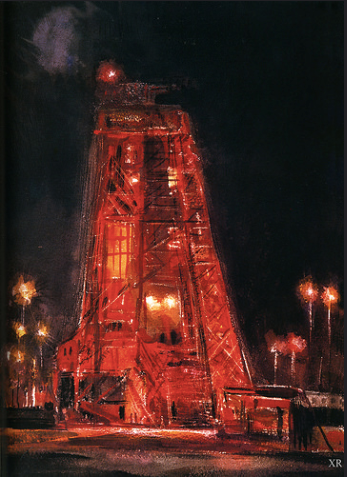

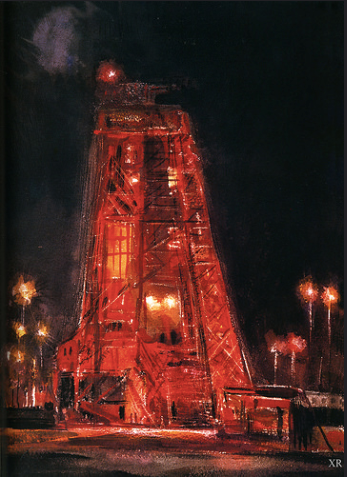

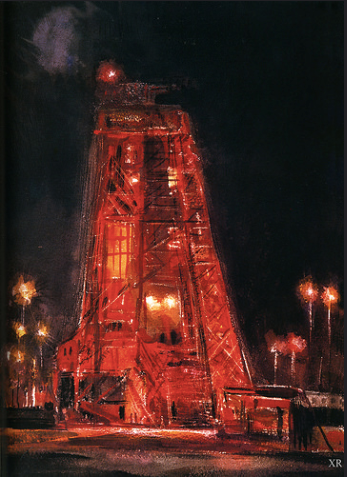

The first mission which the artists had a chance to document was the 1963 Mercury-Atlas 9, the last launch of the Mercury program. The main pilot was Gordon Cooper, with Alan Shepard as a backup.

Mitchell Jamieson’s First Steps portray NASA astronaut Gordon Cooper at the moment he left his Faith-7 spacecraft in 1963. Gordon Cooper emerges from the spacecraft in a full suit, shaking legs, dizzy eyesight – he had just orbited the Earth 22 times.

Mitchell Jamieson managed to grasp this amazing scene thanks to his strategic choice of placement – he watched everything from a landing spot on the Atlantic Ocean, while other artists gathered at the Cape Canaveral spaceport. The paintings and sketches depicting the MA-9 mission were later presented in a traveling exhibit, Eyewitness to Space.

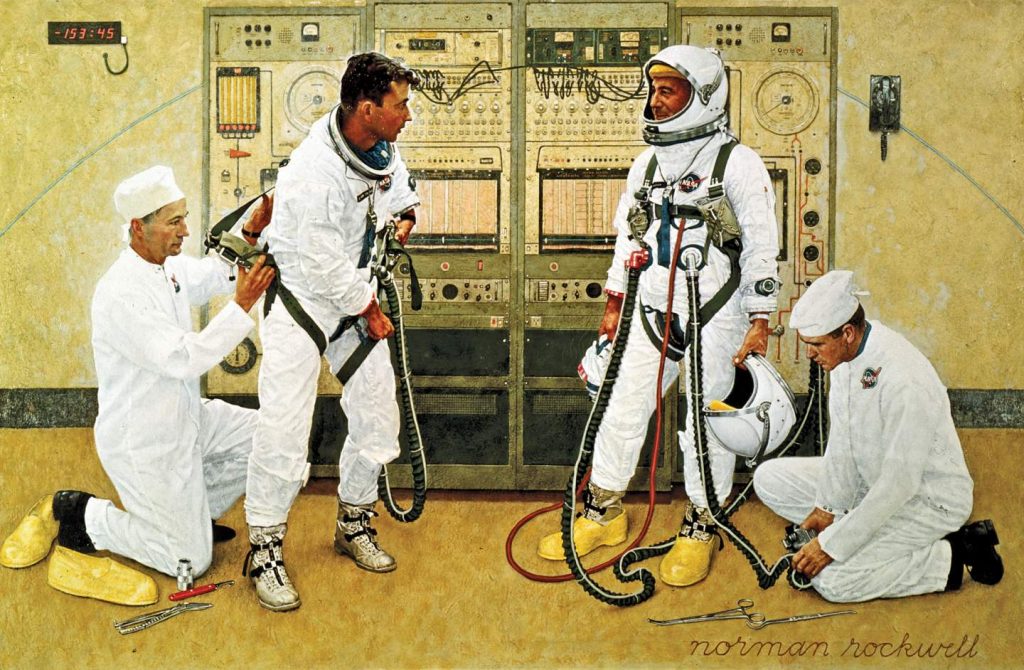

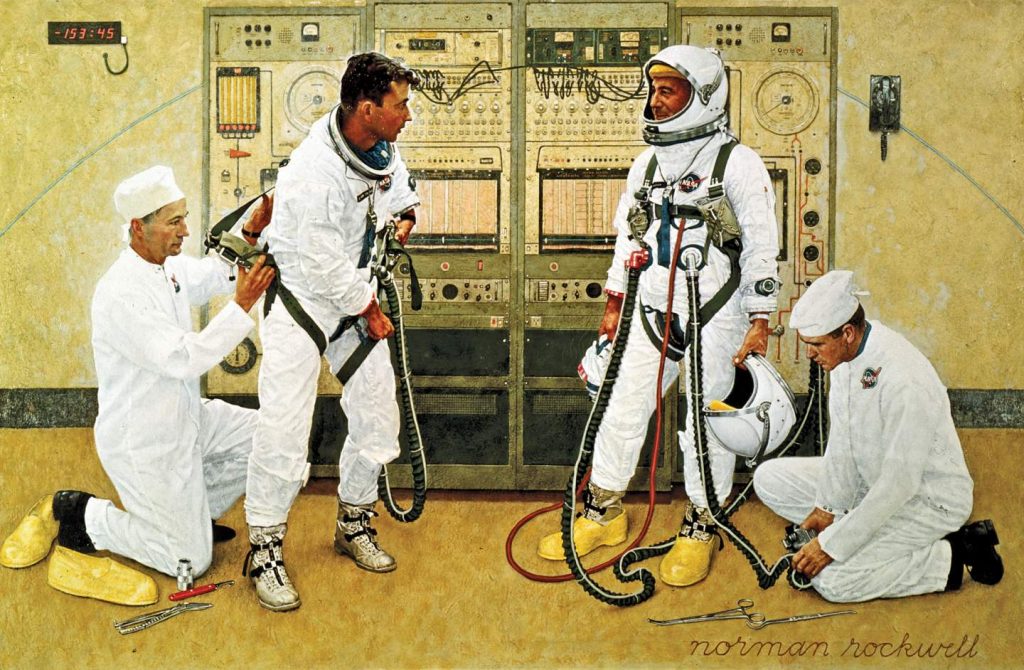

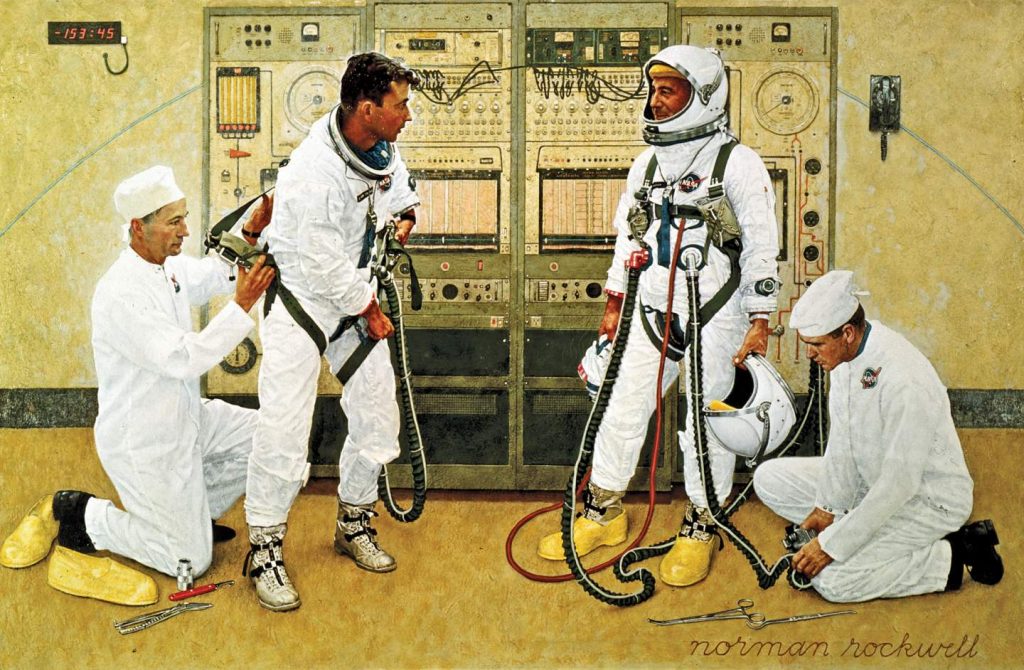

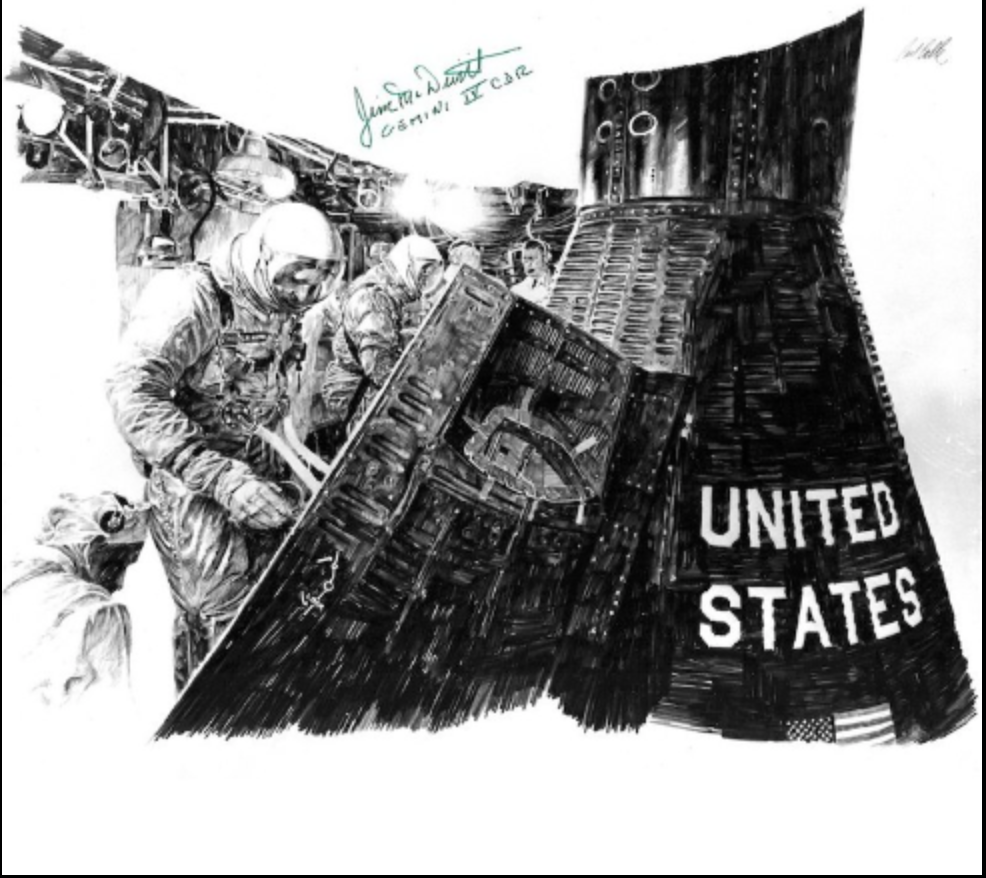

The next works were inspired by the Gemini project, lasting from 1961 to 1966 and focusing on human spaceflight. During this time, Norman Rockwell officially joined the program – which resulted in his Grissom and Young piece.

Grissom and Young, currently part of Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, shows the suiting up of astronauts John Young and Gus Grissom. As we know from the archival records, Rockwell requested to borrow a spacesuit to prepare the sketches and finish the painting in his studio. NASA wasn’t keen on this idea, but they eventually allowed Rockwell to borrow the suit – only if a delegated technician was monitoring. The technician ultimately became a model as well, depicted in the painting as one of the assisting workers.

The astronomical artist will always be far ahead of the explorer. They can depict scenes that no human eye will ever see, because of their danger, or their remoteness in time and space.

Arthur C.Clarke, in Hereward Lester Cooke, Eyewitness to Space.

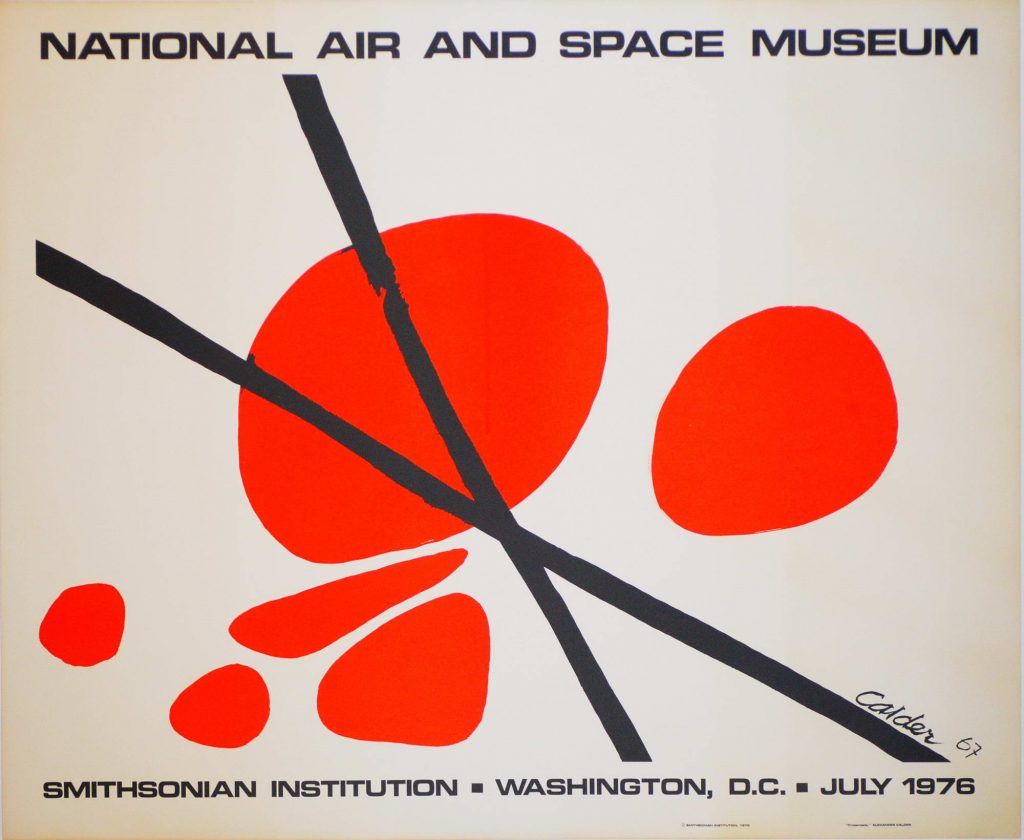

One of the biggest events of the 20th century was the 1969 Moon landing. On July 20th, 1969, two American astronauts (Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin) became the first humans to land and step on the Moon. This “moon phase” brought the most artistic depictions, and the program’s cooperation rules became more specified. The Moon landing was a part of the Apollo program, which ran between 1960-1972. Realist artworks were still dominating, but we can see more abstract compositions, such as Alexander Calder’s Crossroads.

Calder’s Crossroads was reproduced as a poster advertising the National Air and Space Museum‘s opening. The abstract guache lithograph depicts the aforementioned Apollo 11 lunar landing mission.

Most of the artworks created during the Apollo mission phase focus on the historical moment of Neil Armstrong’s steps. This iconic moment was sort of predicted in Norman Rockwell’s Astronauts on the Moon from 1966.

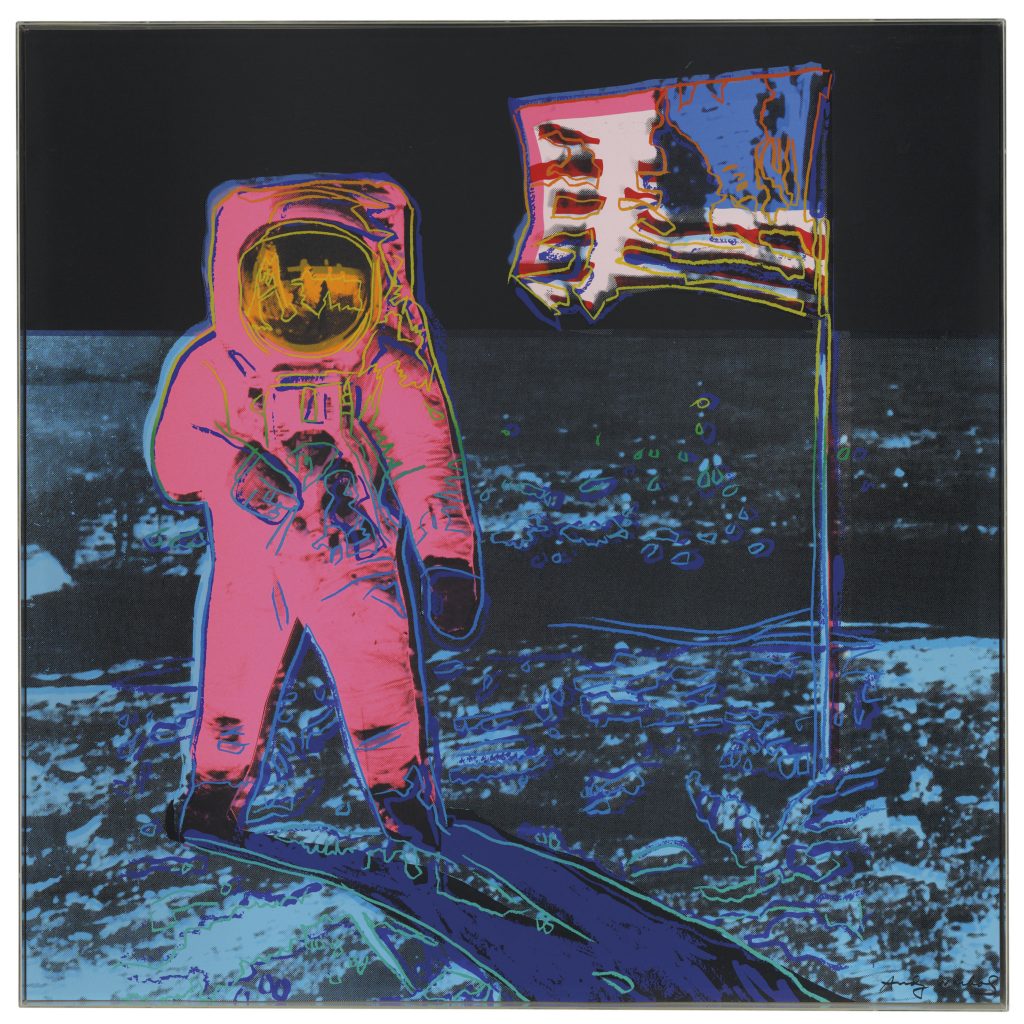

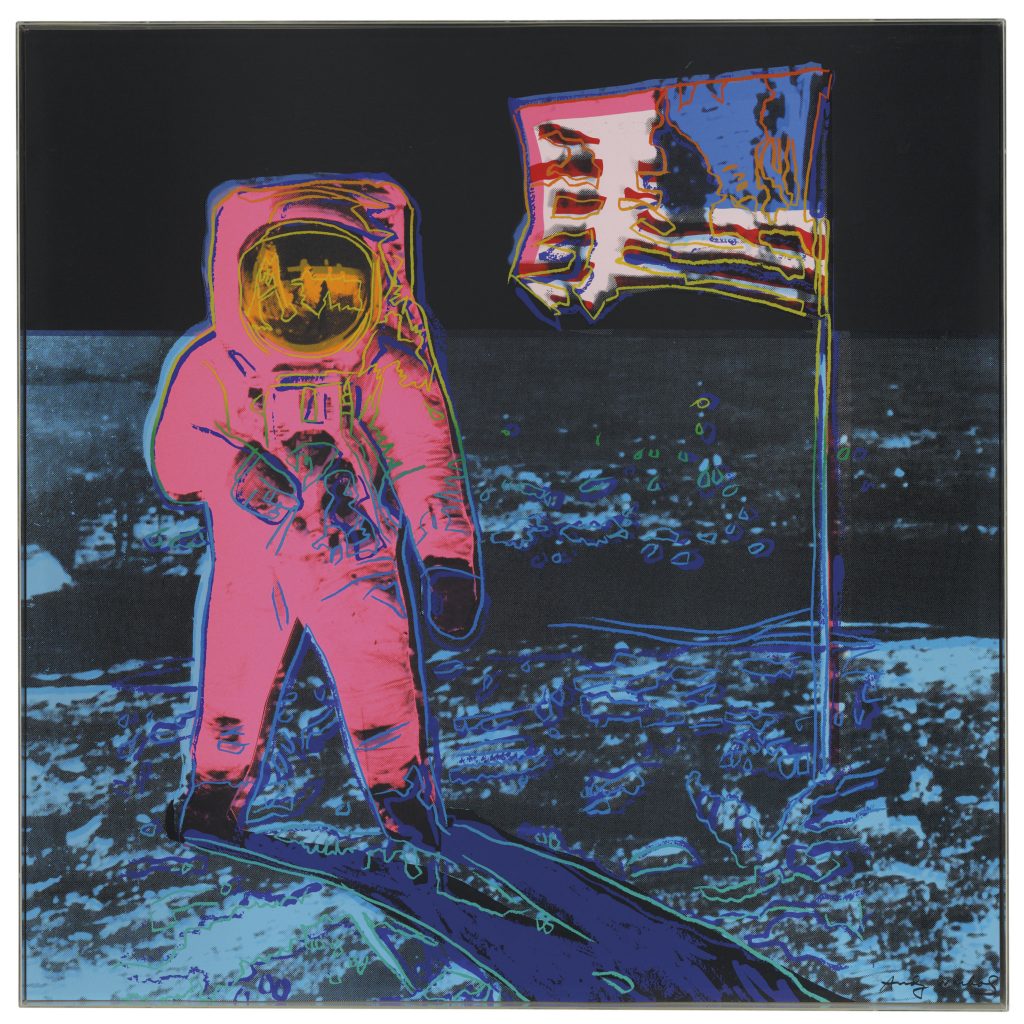

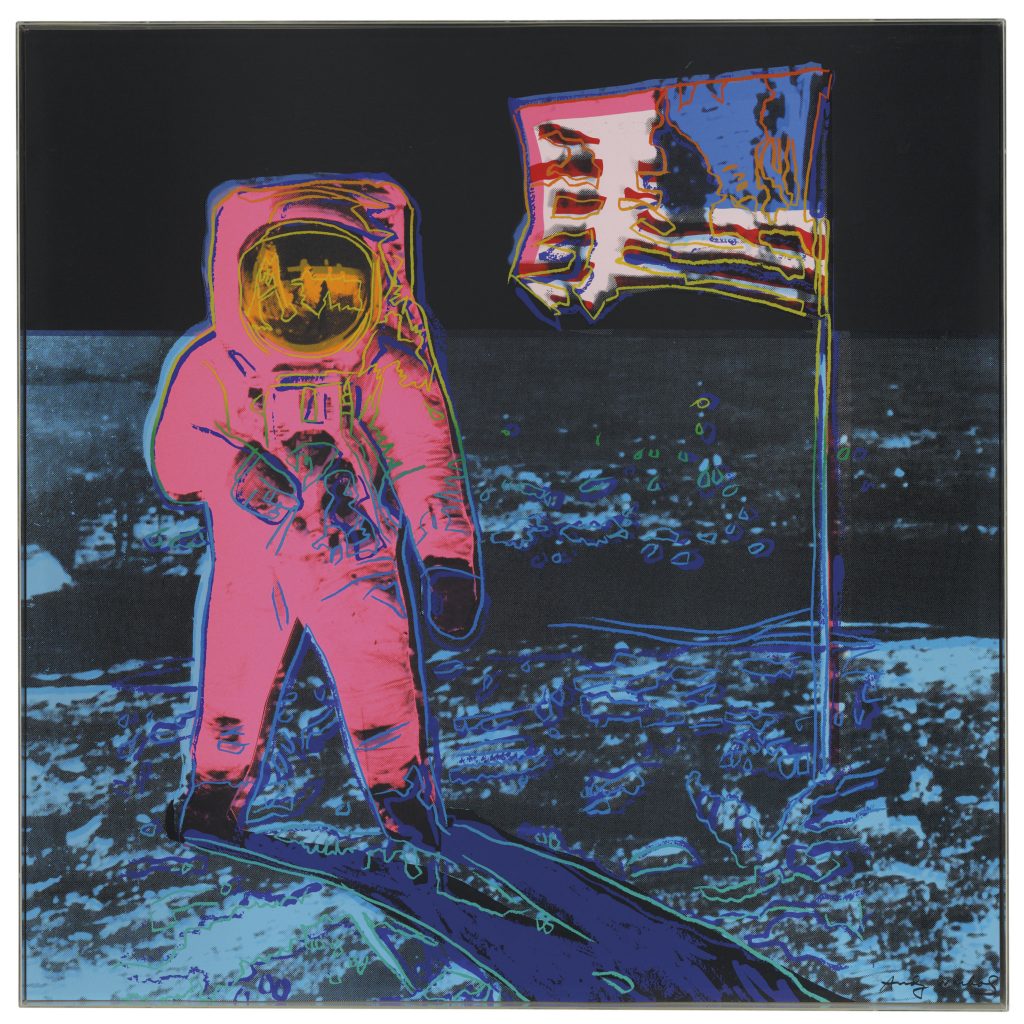

The stars of the collection are Andy Warhol’s Moonwalk screen prints. These are examples of pieces not directly commissioned by the agency, but bought later and included in the NASA Art Collection.

Today NASA’s Art Program isn’t as widely promoted as during the Space Race age – priorities simply changed or slowed down. NASA has kept on romancing the arts, gathering important space-exploration-themed pieces for their collection, nowadays mainly operated through the Smithsonian National Space and Air Museum. This unusual art collection has an archive of over 800 works by 250 artists of different fields – including artists mentioned before but also photographer Annie Leibowitz or the musical Kronos Quartet.

The NASA Art Program was eventually replaced by Artist-in-Residence projects, focusing more on singular artists rather than groups. Just like before, carefully selected contemporary artists get access to research knowledge and know-how, creating new perspectives inspired by historical missions and scientific breakthroughs.

The last “official” residency belonged to an avant-garde performance artist, Laurie Anderson. Her piece was co-created with Hsin-Chien Huang and was a multimedia-driven, virtual reality experience project. The viewers were transported to a virtual moon (celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing in 2019), where they could view some unique constellations created by the artist. Polar bears, dinosaurs… and democracy, modern constellations of things that have disappeared or are quite fragile and are at risk of extinction.

James Dean, Bertram Urlich, NASA/ART: 50 years of exploration, Abrams, New York, 2008. Accessed 18 Dec 2020.

Lawson Bell, Susan, Artistry of Space, ArtTrain Inc., 1999.

Hereward Lester Cooke, Eyewitness to Space, Harry N.Abrams Inc., 1972.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!