Masterpiece Story: The Rainbow Portrait

Queen Elizabeth I is known throughout history as one of the most famous British Queens. Even without a husband, she successfully ruled England for 45...

Anna Ingram 8 July 2024

The Medici family was definitely one of the richest dynasties in Renaissance Italy and perhaps they were the most influential patrons of the arts in history. It was their great wealth that propelled the development of humanist arts and science in Italy. How did a wealthy family of bankers come to be a quasi-monarchy of Florence legitimized with a divine mandate? Here is the story of how some of the greatest art ever created was used to transform a family of rich sinners into an all-powerful dynasty of saintly rulers.

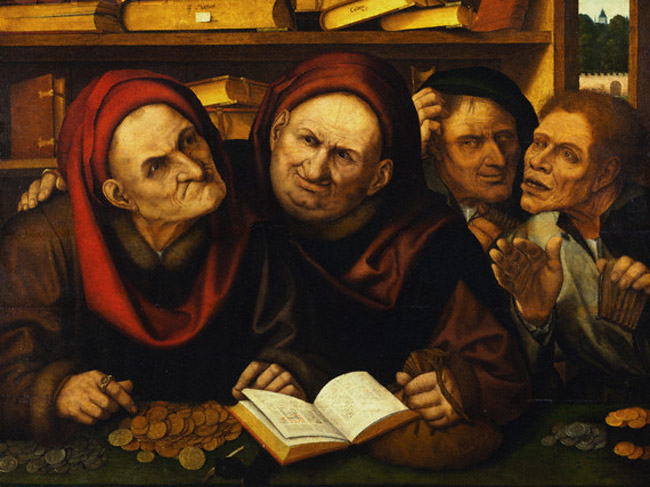

It starts in the markets of medieval Florence in the early and mid-14th century. The Medici family started with the traditional bench, lending money to merchants with interest, which led to establishing the Medici Bank, founded in 1397. However, as their wealth grew, there appeared a moral dilemma. In fact, more than a dilemma, the biblical sin of usury (charging excessive interest in money lending) created a significant barrier to the legitimacy of their power, and more so to their own personal places in the heavens. Why?

Dante’s famous 7th Circle of Hell was specifically reserved for the worst and most violent sinners. So why was there a place for the usurers, and what could be so bad about a white-collar crime as usury? In the Middle Ages, it was considered a serious perversion or violation of the laws. It was also defined differently than it is today: medieval theologians believed that charging any interest at all on a loan was usury. Thomas Aquinas, for example, stated that “it is in accordance with nature that money should increase from natural goods and not from money itself.”

Dante wrote in Inferno, Canto XI:

But still the usurer takes another way:

He scorns nature and her follower, art,

Because he puts his hope in something else.

Whilst the Medici Bank was brought to the forefront by Giovanni di Bicci, it was his son Cosimo de’ Medici who turned that financial power into a political dynasty, and who was perhaps the greatest patron of arts in history. As far as the arts were concerned, Cosimo presided over the golden age of the Italian Renaissance, commissioning works from contemporary masters, such as Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi, Filippo Brunelleschi, and Donatello.

“Cosimo de’ Medici… [was] a citizen of rare wisdom and inestimable riches, and therefore most celebrated all over Europe, especially because he had spent over 400,000 ducats in building churches, monasteries, and other sumptuous edifices not only in his own country but in many other parts of the world, doing all this with admirable magnificence and truly regal spirit since he had been more concerned with immortalizing his name than providing for his descendants.”

– Francesco Guicciardini, The History of Italy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, p. 60.

This quote gives further insight into the Medicis’ mindset. Despite his wealth, power, and generous patronage, Cosimo still carried the ball and chain of usury around with him and his family.

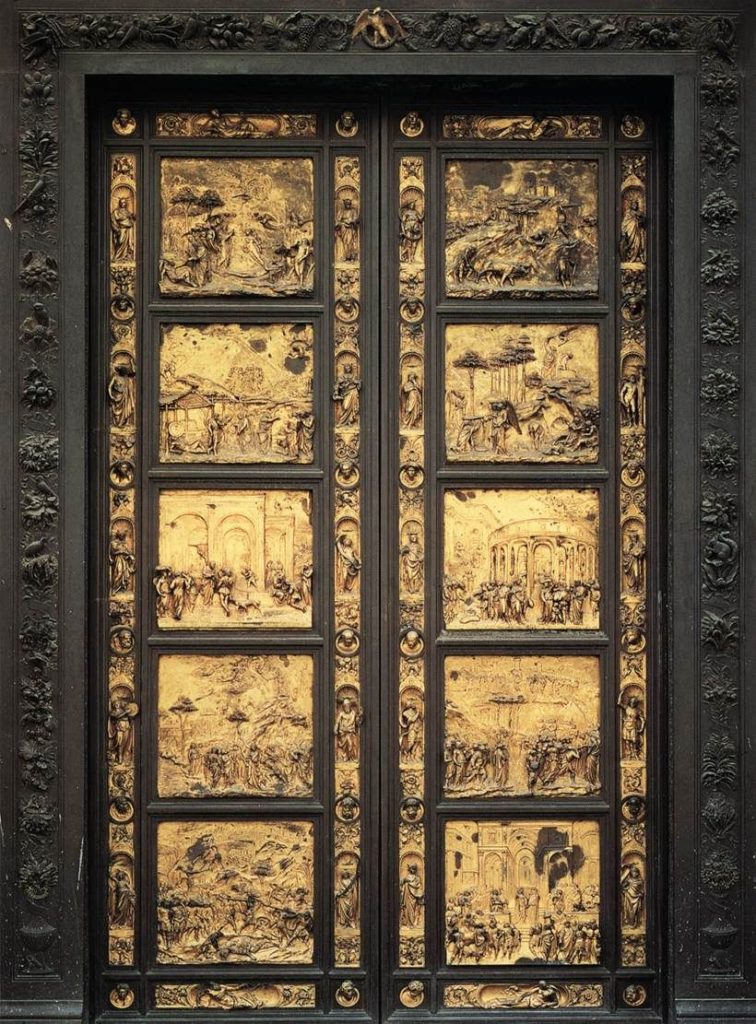

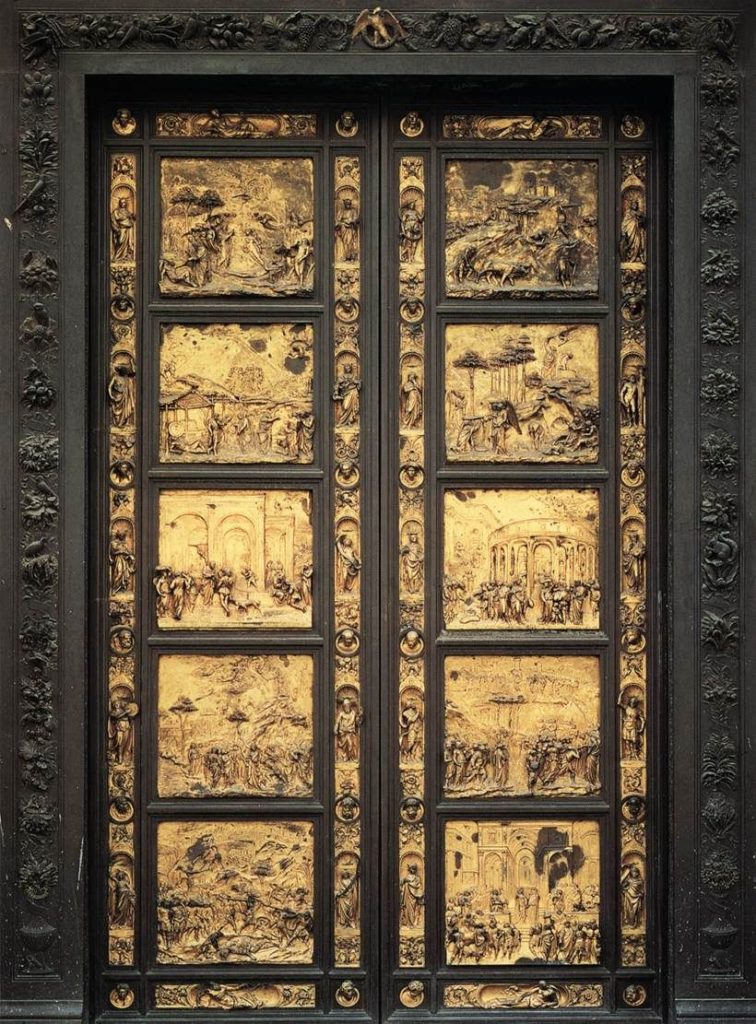

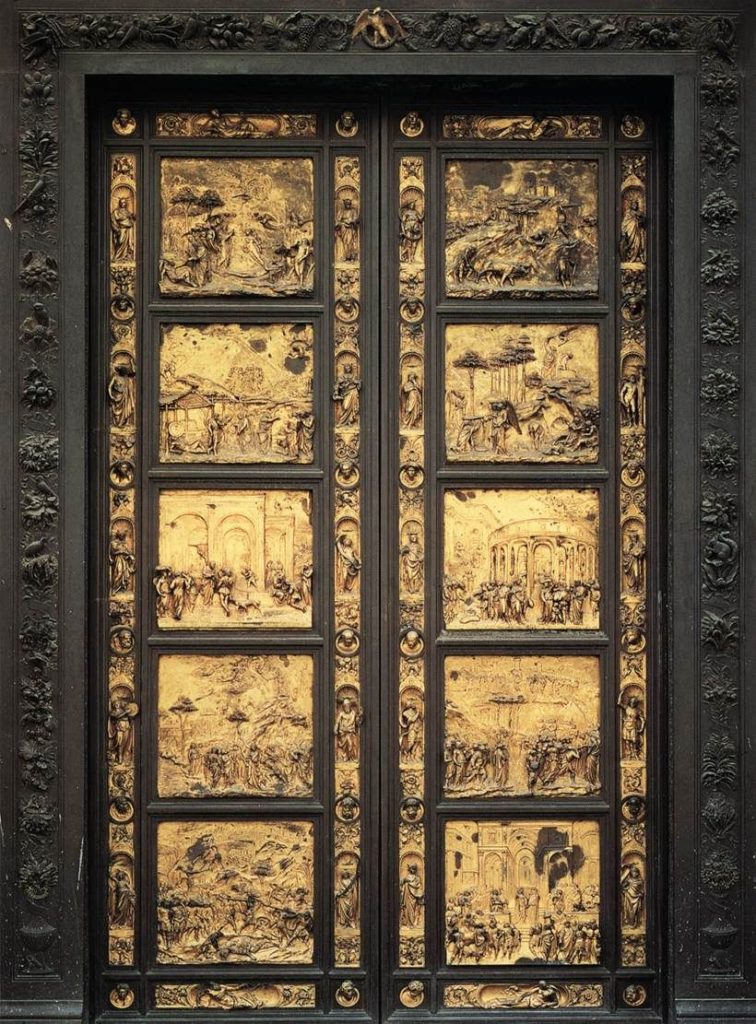

It could be seen what Christianity thought of the fate of the usurer by simply visiting some of Florence’s most beautiful and important buildings. Take, for example, the East Doors (or the Gates of Paradise, as Michelangelo had named them due to their divine perfection) of the Florence Baptistery (across the Piazza from the famous dome of Brunelleschi, patronized by Cosimo). This Renaissance masterpiece of gilded bronze took 21 years to complete. The sinners of usury are depicted in one of the most praised works of art of the period. It is even said that Cosimo himself was baptized there.

Cosimo de’ Medici established his strong political position in Florence due to his wealth. He financed and controlled the municipal councils but he did not hold any public offices. As his influence grew, an anti-Medici party was formed by the Strozzi and Albizzi families who conspired against the Medicis. As effect, in 1433, Cosimo was imprisoned in Palazzo Vecchio and eventually exiled from Florence. Cosimo settled along with his bank in Venice from where he ran his business and continued to commission arts. After a year, Cosimo was allowed to return to Florence as the city suffered financially from the absence of the capital he took with himself to Venice.

On November 1434, Cosimo returned from exile to become the virtual ruler of Florence. Expiating his sins of pride and usury, he magnanimously undertook the reconstruction of the Basilica di San Marco. Put simply, you could buy your way out of hell (sanctioned officially by church doctrine) by sponsoring art and architecture.

At a staggering expense, Cosimo commissioned architect, Michelozzo di Bartolomeo, to rebuild San Marco’s cell cloister and choir. He also fed and clothed the monks and funded the great library. San Marco was an austere order of Dominicans who lived in simple cells, however, each containing a sublime single fresco by Fra Angelico for spiritual contemplation. Pope Eugenius consecrated the church on the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6, 1443. Fra Angelico was at the height of his fame, decorating each of the cells and the convent interiors.

Cosimo had his own cell in the convent for his own worship and contemplation (albeit with a passageway back to the “real” world outside). So the Medicis were off the hook? Cosimo’s contribution to the church had officially expunged their sins and they had support from the Pope and a divine authority to rule. Even a plaque laid at Basilica di San Marco states this effect.

Who in the Bible was rich and good? The answer was The Magi (Three Kings) whom the Medici became obsessed with. In The Makers of Modern Art, a BBC Documentary, art historian Andrew Graham Dixon states “they joined a fraternity celebrating them [The Magi] and wanted the rest of Florence to join.”

The pinnacle of this obsession was realized in The Magi Chapel in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi constructed by the aforementioned Michelozzo. Its walls are almost entirely covered by a famous cycle of frescos by Renaissance master Benozzo Gozzoli, painted around 1459 for the Medici family.

Gozzoli’s fantastical Journey of the Magi that perhaps represents best of the Medicis’ belief in their own place as divine rulers, casting themselves as part of the holy procession, dressed in all the glory of wealth, power, and magnificence.

Cosimo was the smart one and transformed the Medici status not just in the eyes of every Florentine but in the eyes of God, on their own journey, from sinners … to not far off sainthood!

Andrew Graham Dixon

In the aforementioned documentary, Andrew Graham Dixon described the chapel as “a celebration of the sheer marked joy of capitalism.” It announces and reaffirms that wealth and power can be good and godly. You just needed the greatest art by the greatest masters to help communicate it.

One can’t help but wonder, wasn’t all this gold and finery, wealth, and power at odds with Christ’s life, his suffering, and the humble simplicity of his teachings? Have the Medicis gone too far trying to rid themselves of the sinful label of usury?

Perhaps the answer lies in another famous Florentine church, Basilica di San Lorenzo, where many of the principal Medicis were buried.

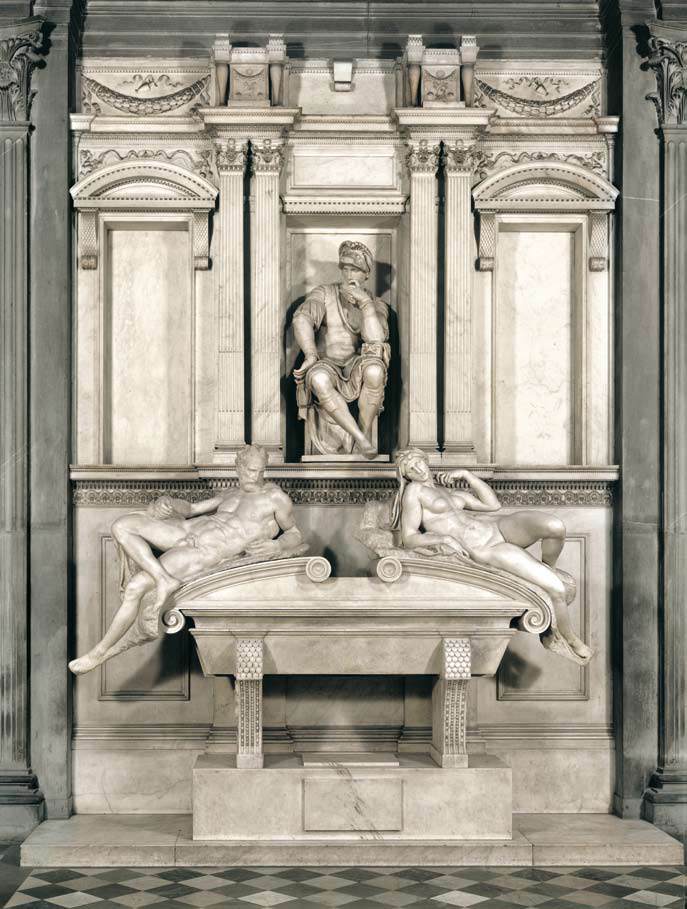

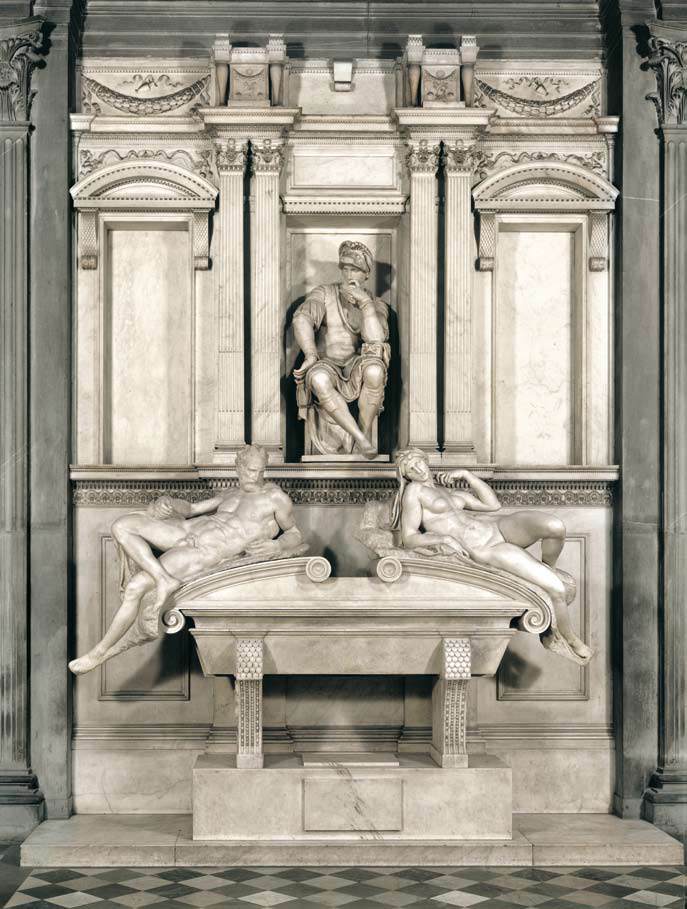

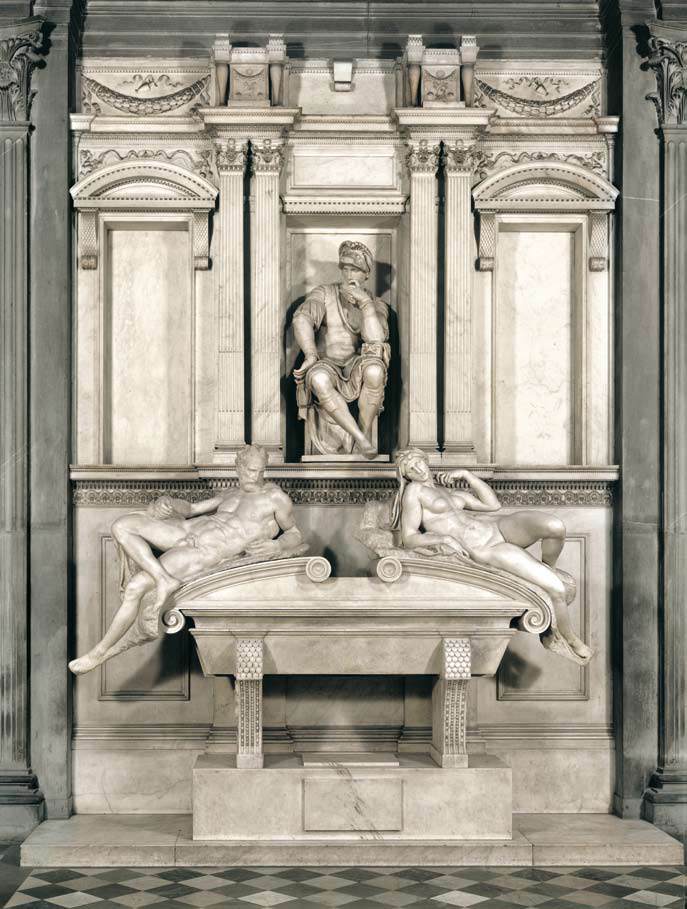

By the time Michelangelo had begun work on the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo in 1520, the halcyon days of Medici power were already in decrease. They would be powerful for another century but the direct rule of Cosimo was firmly behind the family. His notable grandson, Lorenzo de’ Medici (called also Lorenzo the Magnificent), let the Medici Bank decay as he concentrated on running the Florentine state. Times had changed with the later Medici members completing the transition from merchants to aristocrats, and eventually popes.

Michelangelo designed a number of tombs dedicated to various members of the Medici dynasty in the Medici Chapel. He never finished the entire project, as he permanently left to Rome in 1534, so most of the sculptures were later installed by Niccolò Tribolo in 1545. What had started as a project by arguably the greatest sculptor of that time, commissioned to ensure the eternal memory of the greatest Medici, became a symbol of their decline in power.

Michelangelo might have also had the final say. In the artist’s biography, by Ascanio Condivi, we read:

“The statues are four in number, placed in a sacristy…The sarcophagi are placed before the side walls, and on the lids of each there recline two big figures, larger than life, to wit, a man and a woman; they signify Day and Night and, in conjunction, Time which devours all things… And in order to signify Time he planned to make a mouse, having left a bit of marble upon the work (which [plan] he subsequently did not carry out because he was prevented by circumstances), because this little animal ceaselessly gnaws and consumes just as time devours everything.”

Is it the great man’s way (who himself had a mixed relationship with the Medici family – sometimes he was hiding from them) of saying that for all the wealth, power, finery, and glory, ultimately nothing lasts? A statement all the greater for being placed at their own sacred front door.

Whilst Cosimo and Lorenzo did appear to transform the family from wealthy sinners into divinely endorsed rulers, Michelangelo shows us that ultimately everything that rises must fall, and eventually turns to dust. But it was certainly the wealth of the Medicis, and also their passion to become something more, something else, that bought us some of the finest art of the Renaissance period, as well as a legacy of architecture, philosophy, and learning. For this, we must all thank them.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!