The Greatest Male Nudes in Art History (NSFW!)

Nudity started being an important subject in art in ancient Greece. The male body was celebrated at sports competitions or religious festivals, it...

Anuradha Sroha 19 November 2024

18 August 2021 min Read

“I am human, and I think nothing human is alien to me”, said Terence, Roman playwright sometime in the 2nd century BCE. I think that art and what inspired what you will see below, is exactly this: human imperfections, human needs, human dreams, human psyche… It might scandalize some, but the world in the eyes of Hans Bellmer is a scandalous one anyway.

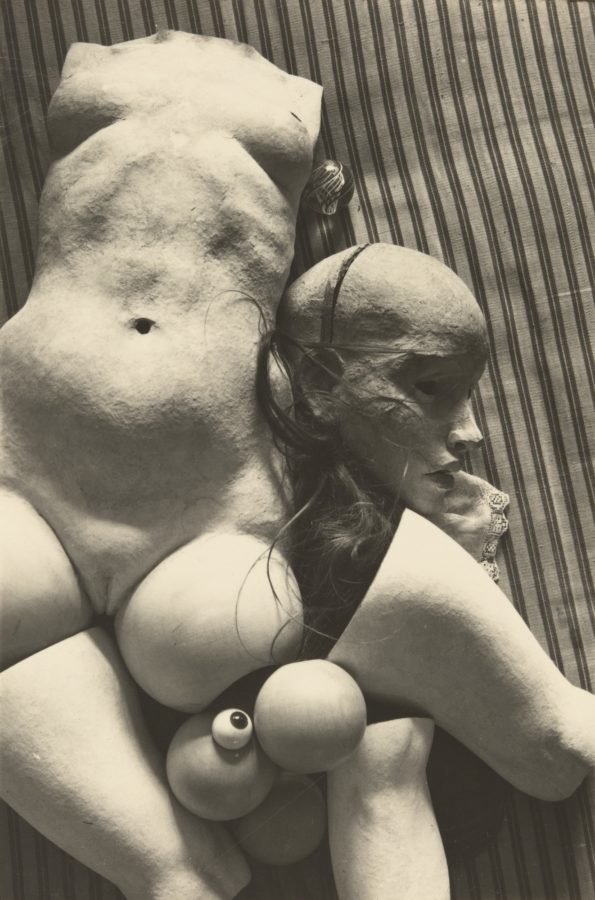

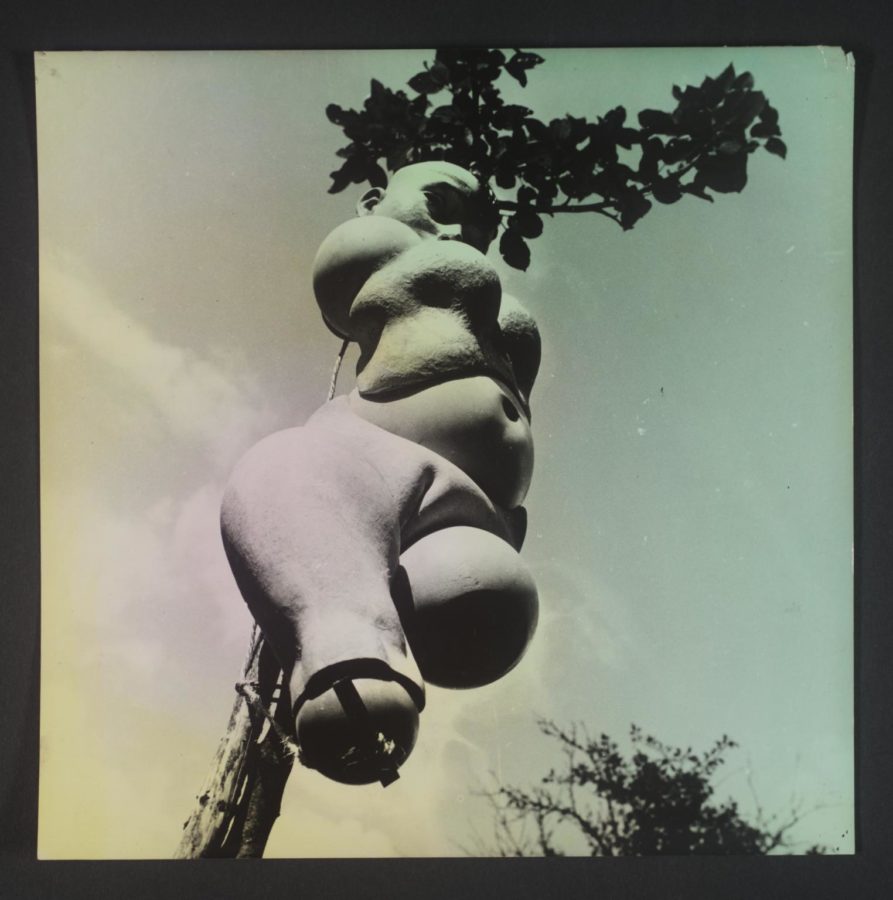

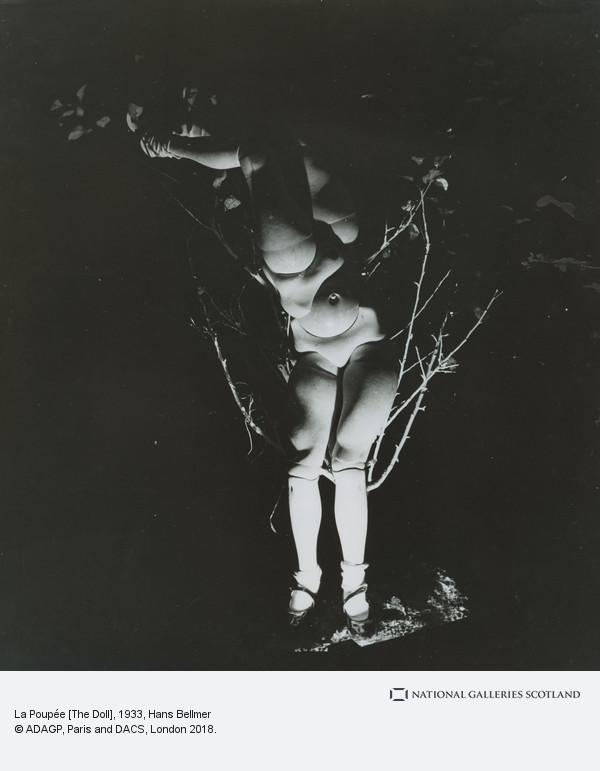

Hans Bellmer was born in 1902 in German Kattowitz (today’s Katowice, Poland), and held his first exhibition at the age of 20. Having completed high school, he worked in a mine until, under the influence of his father, he moved to Berlin to study at the Technische Hochschule, which brought him to meet Otto Dix and Georg Grosz. In 1924, he left university to work full-time as a draughtsman and illustrator. Ten years later, he officially withheld from any public activity in an act of protest against the Nazi overtake of Germany. In the following years, he returned often to his parents’ summer house in Bad Karlsruhe, where he continued working on his projects of life-size dolls, which he began in 1933, photographing them in the garden and in the house interior. In 1934, he published anonymously a book of ten photographs documenting the stages of the doll’s construction called Die Puppe (the doll) (reprinted in French, as La Poupée, in 1936). Paul Éluard then printed them in the December 1934 issue of the Surrealist journal Minotaure, annotating them with his poems.

His dolls clearly opposed the Nazi cult of perfect body, as they were skewed, dismembered, and ugly. Bellmer made his first doll inspired by the beauty of his young cousin Ursula, but he was also under the strong impact of Jacques Offenbach’s fantasy opera Les Contes d’Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann, 1880), in which the hero, in love with an uncannily lifelike automaton, ends up committing suicide. Called a degenerate artist in 1937, Bellmer didn’t hesitate to move to France, especially as his first wife Margarete died of tuberculosis in the same period. In Paris he was embraced by the Surrealists, especially André Breton, and during WW2 Bellmer supported the French by producing fake passports; he was subsequently imprisoned in the Camp des Milles prison for German nationals at Aix-en-Provence, where he did brickwork until May 1940. In 1942 he married again and had two daughters, and in 1944 he illustrated a novella, Story of the Eye by G. Bataille, which describes the sexual perversions of two teenage lovers. After the war, Bellmer stopped making dolls and moved onto photography and painting which explored themes of sexuality, fetishism, and dreams.

In an interview with Peter Webb, he explained:

“I was aware of what I called physical unconsciousness, the body’s underlying awareness of itself. I tried to rearrange the sexual elements of a girl’s body like a sort of plastic anagram. I remember describing it thus: the body is like a sequence that invites us to rearrange it, so that its real meaning comes clear through the series of endless anagrams. I want to reveal what is usually kept hidden – it is no game – I tried to open peoples eyes to new realities: it is as true of the doll photographs as it is of Petit Traite de la Morale. The anagram is the key to my work. This allies me to the Surrealism and I am glad to be considered part of that movement, although I have less concern than some surrealists with the subconscious, because my works are carefully thought out and controlled. If my work is found to scandalise, that is because for me the world is scandalous.”

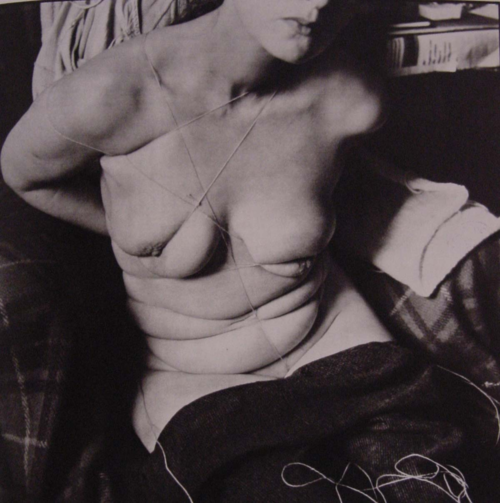

In 1953, Beller met artist and writer Unica Zürn with whom he began to collaborate (and have a romance). Their most famous work is the photographic series Unica Zürn Tied Up, in which close-up photographs of female body bound by a tight rope is an artistic exploration of sadomasochistic practices. They were united in life and work until the year of her suicide, 1970.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!