10 UNESCO World Heritage Sites to Visit in France During the Olympics

Visitors to the Olympics will not only be able to enjoy the sports while supporting their favorite countries and athletes. France offers an unusual...

Ledys Chemin 29 July 2024

1887 saw a significant discovery in the field of medieval art, though at the time nobody, not even the discoverer himself, was aware of the real value of his find. He actually found Camelot, a piece of Arthurian art in Poland.

The discoverer was one Wilhelm Klose, the tax inspector from Hirschberg, today’s Jelenia Góra in Poland. What precisely was he doing in a medieval tower, sitting on the picturesque bank of the River Bobber, and how he came across a treasure, one can only guess. Was it a flair for history or just daily business that brought him to the estate of the powerful Schaffgotsch family in the village of Siedlęcin? Whatever it was, it was here he made his discovery.

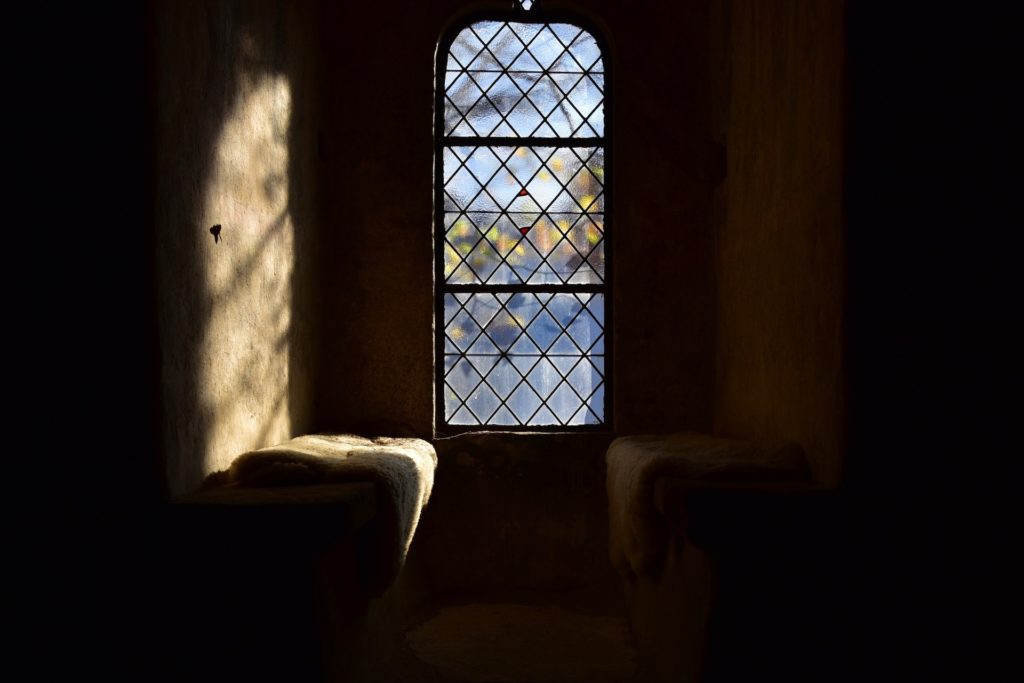

The tower had been built long before the Schaffgotschs appeared. Today it is one of the largest and best preserved tower-houses in Central Europe. Its fabric dates from the early 1320s, when it was founded by Duke Henry I of Jawor. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Schaffgotschs had a manor house built in front of it.

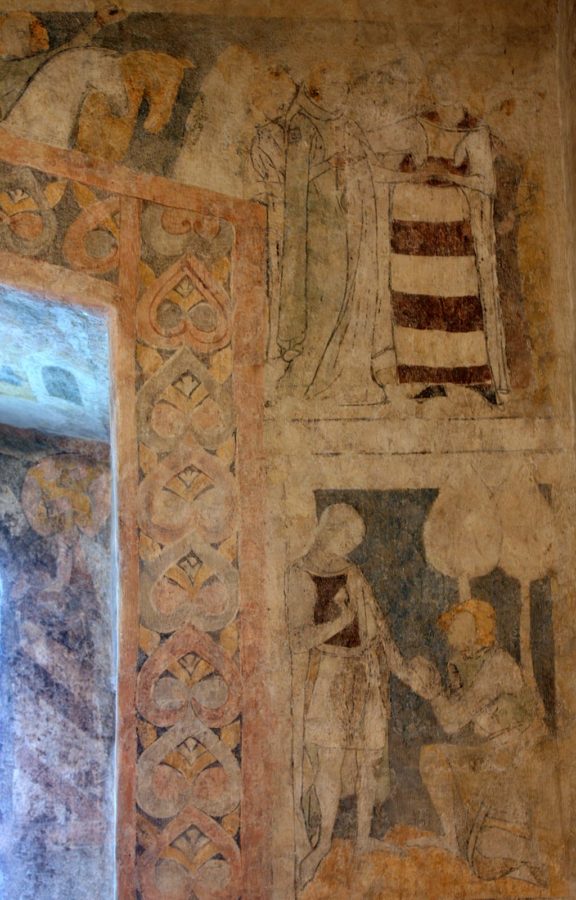

During his visit, Wilhelm Klose made a remarkable discovery in the tower’s former Great Hall. He uncovered some paintings from underneath the layer of whitewash. At first, he did not know what they depicted. What he could distinguish was a large figure he took for Virgin Mary and a few scenes depicting knights and their exploits. However, he could not have known that he uncovered only a part of a whole set and the southern wall was adorned with more paintings awaiting discovery. The inspector described what he saw in a meticulous detail. As a result, his account has become one of the major sources in the scientific research carried out at the tower today. The years passed and in 1913 the upper register of the paintings was brought to light.

It took art historians almost one hundred years to determine the true identity of the paintings’ main character. As it turned out, they depicted sir Lancelot of the Lake himself. Ever since Chrétien de Troyes wrote his famous romances and the alleged tombs of King Arthur and Guinevere were discovered at Glastonbury, Europe burned with Arthurian zeal which from the British Isles and today’s France spread as far as the Iberian Peninsula, Italy, and Scandinavia. The romances featuring both Arthur himself and his valiant knights also made their way to the courts of Central Europe. Pages of the manuscripts, castle walls, and objects of everyday use were decorated with scenes depicting their marvelous exploits. Children of nobility and knightly families were named after the Arthurian characters.

In the ducal tower of Siedlęcin, the story of King Arthur’s greatest knight, his glittering career, adulterous love for Guinevere and subsequent downfall has been told in two registers and should be ”read” from the lower to the upper one, from left to right, as in the case of many other examples of medieval cycles.

The lower register shows Sir Lancelot and his cousin Sir Lionel claiming the world shortly after they had been knighted. They set off for their first big adventure to prove their valor and knightly skills in hand-to-hand combat. Eventually, weary of their wanderings, they decide to take a rest. Lancelot falls asleep underneath an apple tree. Lionel is supposed to keep vigil, but falls asleep as well, a negligence he will pay for dearly, for he is attacked and imprisoned by Tarquin.

Tarquin is a knight hostile to Lancelot, who slew his brother. His hatred for Lancelot already had led him to kill a hundred good knights and maim just as many. When Lancelot wakes up and realizes Lionel is gone, he encounters Tarquin, defeats and kills him. Their duel is depicted in the paintings. Thanks to Lancelot’s victory, sixty-four knights, including Lionel and three other knights of the Round Table, obtain their freedom.

In the upper register we can see fair Guinevere with her ladies before the walls of Camelot. Lancelot, accompanied by other members of the court, presents himself to her. The next scene shows the wicked knight Meleagant as he carries the queen away. However, as we remember, he is going to be ultimately slain by Lancelot. Next, the latter hurries to his lady’s rescue, suffering among many other hardships, a total humiliation of riding in a cart, a form of travelling reserved for criminals. He rescues the queen in the end, the sinful nature of their love being shown in a depiction where they hold their left hands, a clear symbol of their adulterous affair.

In addition to the Lancelot story, wall paintings at Siedlęcin display strong Christian symbols. Put together the central depiction of St Christopher (Wilhelm Klose’s Virgin Mary), combined with the scene called Memento mori, and the Lancelot set, the paintings carry a clear moralistic message: a knight should be, in opposition to Lancelot who betrayed his sovereign, as faithful and obedient as St Christopher, who carried the infant Christ across the water on his shoulders. The Siedlęcin set has never been completed, perhaps due to its founder’s death or for more down-to-earth reasons such as lack of means to continue the expensive work. The unfinished portion can be seen on the western wall of the Great Hall.

According to art historians, the artist himself must have come to Silesia from northern Switzerland, from such important centers of courtly art and culture as Zurich and Constance. In style, the Siedlęcin paintings bear close resemblance to the paintings preserved in one of the burgher houses in Zurich, but, first and foremost, to those surviving in the nearby Winterthur, in St Arbogast Church.

Today, the Siedlęcin wall paintings are the world’s only Lancelot paintings preserved in situ. Consequently, they rank among the most outstandingly complete and well preserved medieval murals in Europe.

Author’s bio:

Katarzyna Ogrodnik-Fujcik is a teacher, medievalist and freelance writer. She works with different magazines and websites on Polish and European history. She runs a blog dedicated to Henry the Young King.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!