The paintings in the Lucian Freud: Monumental exhibition in Acquavella Gallery on the Upper East Side in New York City are monumental in many ways, and the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition feels monumental as well.

Freud originally painted with fine sable brushes, standing intimately close to his models, whom he rendered with painstaking care. His brushstrokes at this time were barely noticeable. As the catalogue points out, this way of working led to headaches, and when Freud shared his discomfort with fellow artist Francis Bacon, Bacon gave Freud a coarse hog hair brush to play with. That hog hair brush changed everything.

The hog hair brush made every brushstroke visible. Each unselfconscious pile of paint, varying in color and texture, began to shimmer and glow and dance across the canvas, creating skin textures that can be touched and moved and held with the same freedom as the brushstrokes that made it.

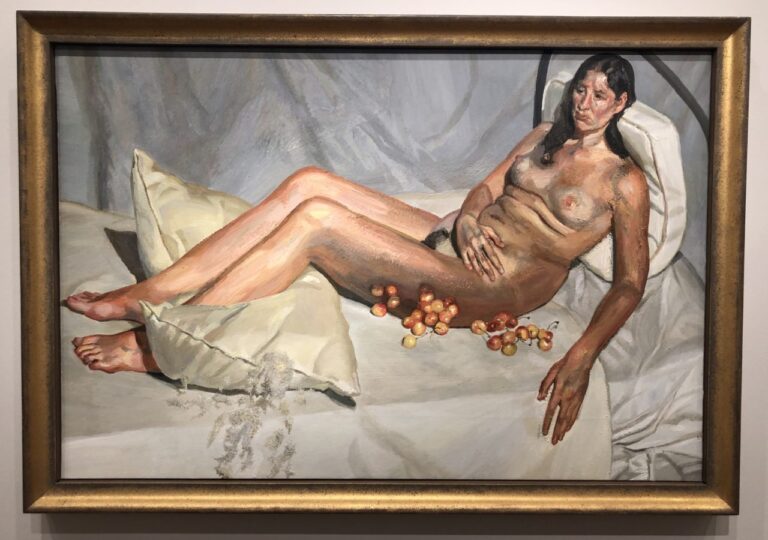

In 1990, Freud met the performance artist Leigh Bowery, who introduced him to Sue Tilley. Both Bowery and Tilley posed for Freud; their large physical bodies led to large, monumental canvases. Freud painted his models without judgment and without idealization. The irony is that in doing so, the inner beauty of both models is allowed to shine through in a way that an idealized version of the real thing would feel ugly and artificial by comparison. The catalogue includes a photograph of Sue Tilley, posing for Benefits Supervisor Sleeping from 1995. I felt as if I were catching a glimpse of an intimate friend, whose inner beauty is interspersed with a wary view of the world.

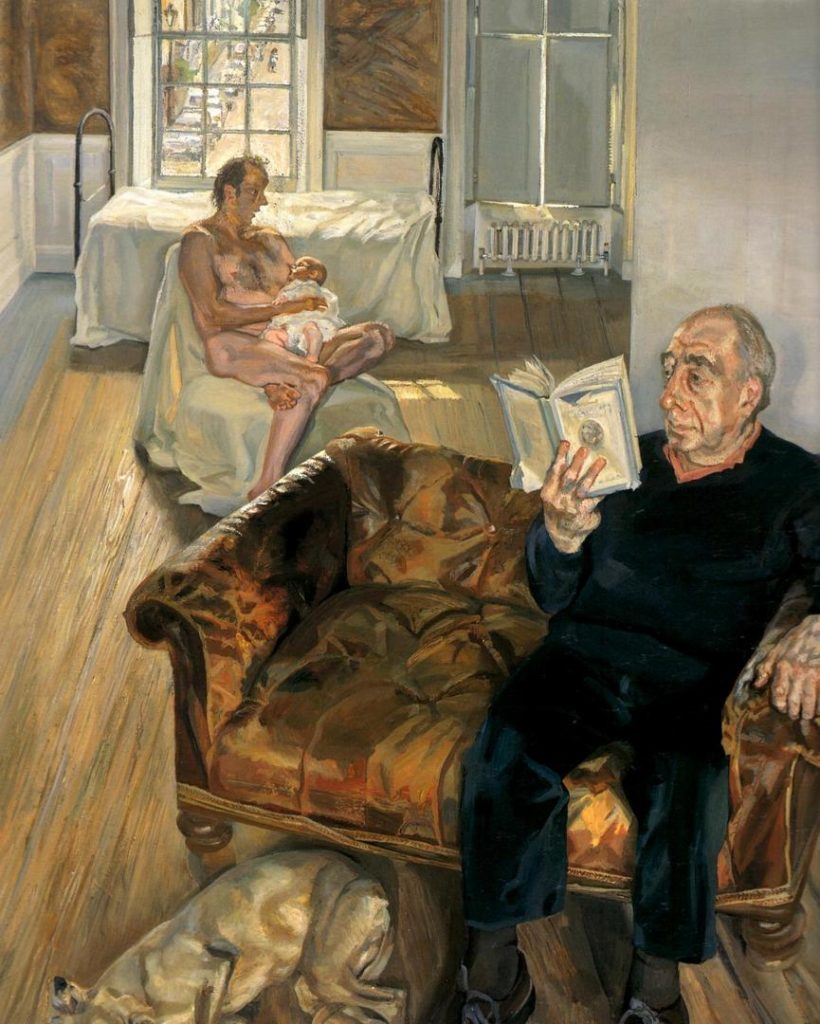

Of all the paintings in this exhibition, the most intriguing one is Large Interior, Notting Hill, from 1998. The fully clothed figure in the foreground is sitting on a small sofa, reading a book, with the family dog asleep alongside him. In the background is a nude figure breastfeeding a baby. The nude figure was originally supposed to be that of Jerry Hall, former wife of Rolling Stones lead singer Mick Jagger. When Ms. Hall was no longer available to pose for the painting, Freud invited David Dawson, Freud’s assistant and fellow painter, to pose in her stead. The outcome is a surprisingly tender painting that makes the change of model feel almost incidental. The painting has many rectangles with many sizes and shapes, and one feels the depth of this quiet room going back to the windows and the street scene beyond. This treatment of the space feels far more expansive than that of Cezanne and Matisse and many other artists from a century earlier. With those artists, the picture plane is more compressed and the two dimensional is given precedence over three-dimensional space.

Lucian Freud is quoted in the exhibition:

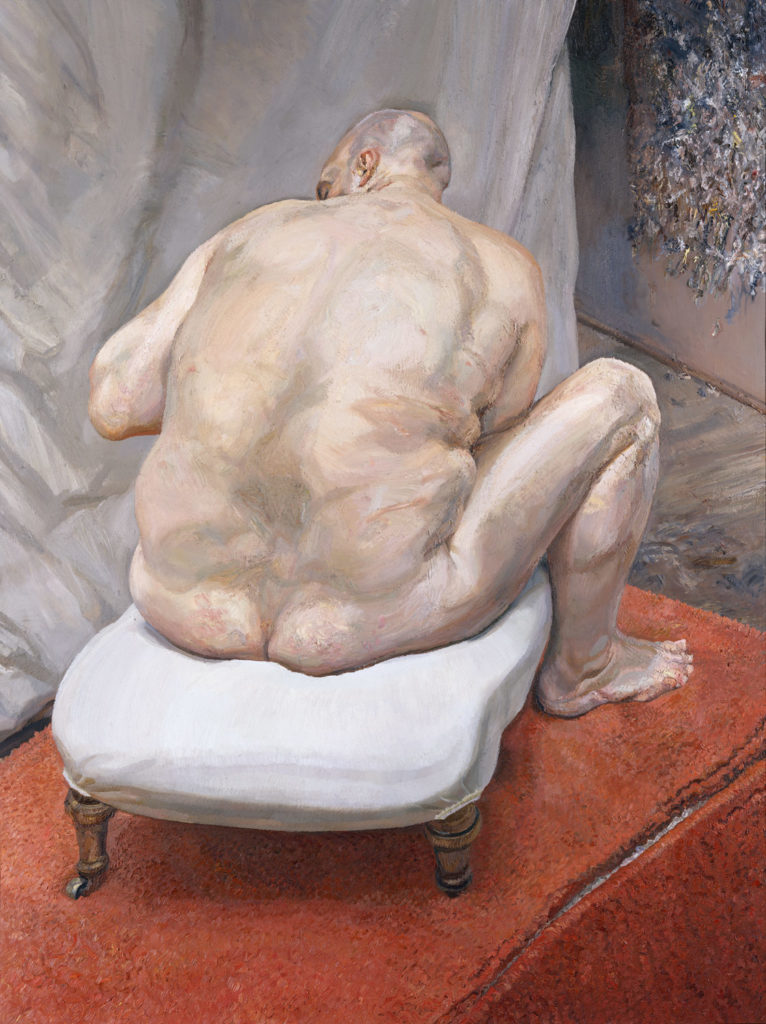

“Being naked has to do with making a more complete portrait, a naked body is somehow more permanent, more factual…When someone is naked there is in effect nothing to be hidden.”

Naked Man, Back View, 1991-92 is an example of this. Leigh Bowery’s back is to the viewer; he is seated at a low level, his legs compressed into his torso. Is this one of the ways Kenneth Clark thought of the unclothed figure in his book ‘The Nude?’

This exhibition, which was curated by David Dawson, took place in May 2019, in Acquavella Gallery.