10 Facts You Didn’t Know About Anthony van Dyck

Anthony van Dyck, a Flemish Baroque painter of remarkable skill, left an indelible mark on art history. His signature style of refined portraits and...

Jimena Aullet 24 October 2024

The Night Watch painted by Rembrandt van Rijn is a monumental canvas displayed today in the “Gallery of Honour” of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Holland’s largest and most prominent museum. Read 15 things you didn’t know about The Night Watch to learn why this very painting is so important and famous in Western art history.

Rembrandt van Rijn, who is considered the most important figure of the Dutch Golden Age received the commission for this particular group portrait in around 1639. The work was finished by 1642 and depicted, on a colossal scale (363 cm × 437 cm or 142.9 in × 172.0 in,) the marching out of the members of civic militia guards (schutterij).

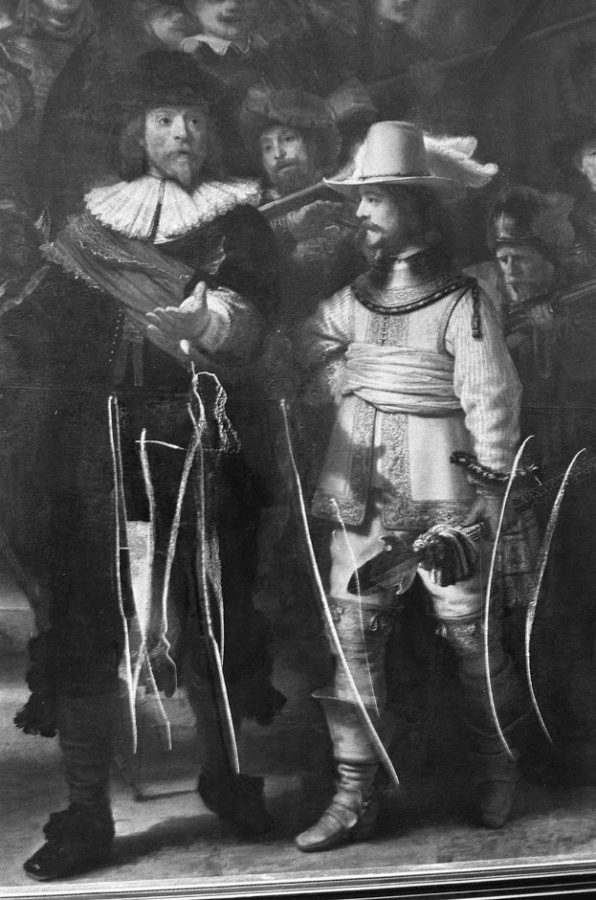

The leading guardsman, Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, who is leading the group is depicted in the center of the composition dressed in black with a red sash. His lieutenant, Willem van Ruytenburch, is seen on his left side standing out from the dark background with his yellow attire.

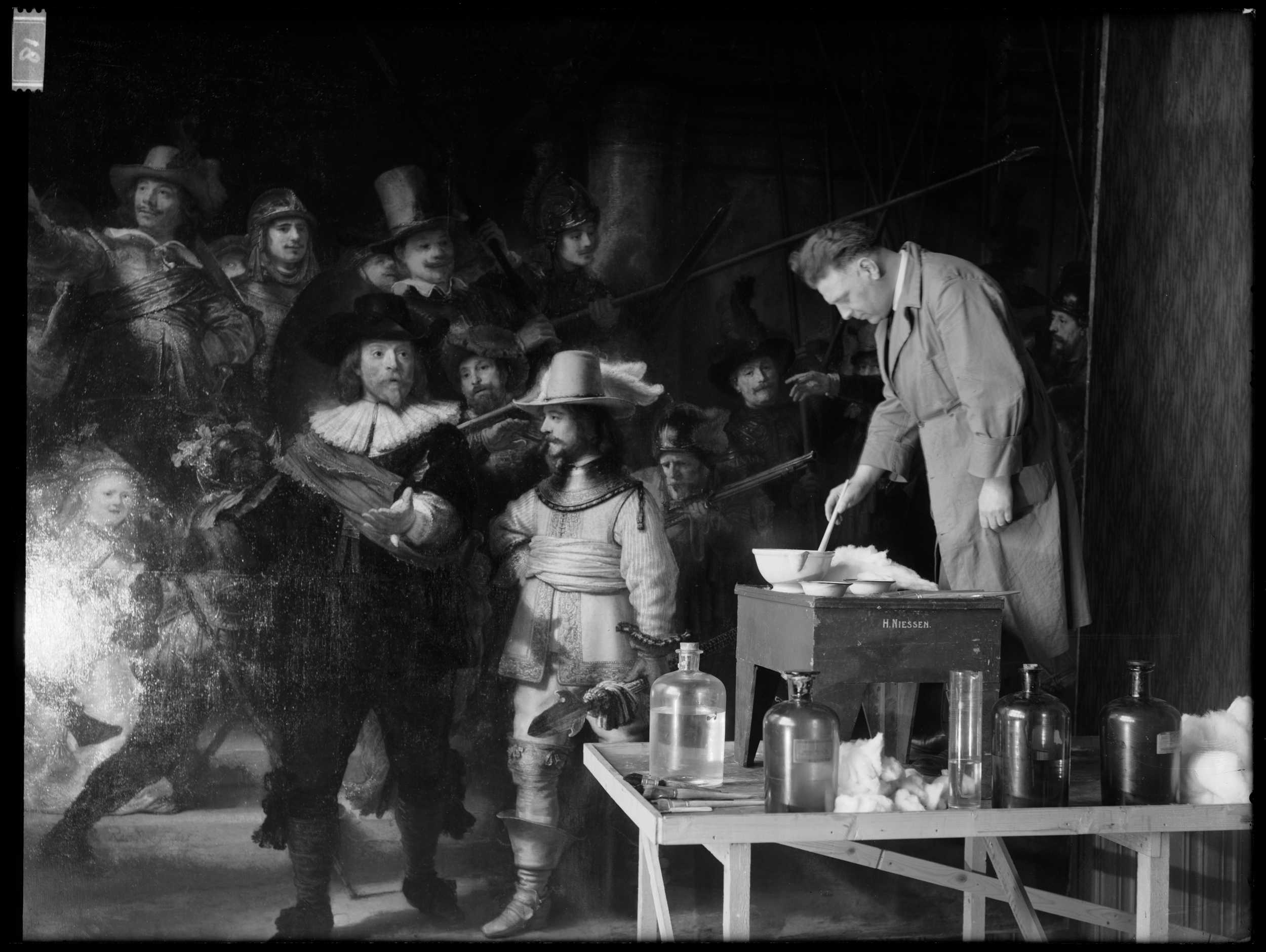

For hundreds of years, the painting was coated with a dark varnish and dirt, which misled scholars into thinking that it depicted a nocturnal scene, hence its common title. In fact, throughout the centuries the layer of varnish grew so thick that it protected the canvas from a knife attack in 1911. The varnish was eventually removed in the 1940s, but the title remained.

By the way, the official version of the title is Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq (Dutch: De compagnie van kapitein Frans Banninck Cocq en luitenant Willem van Ruytenburgh maakt zich gereed om uit te marcheren). We prefer The Night Watch version.

The large canvas was commissioned to hang in the banquet hall of Musketeers’ Meeting Hall (Kloveniersdoelen) in Amsterdam. Kloveniersdoelen served as headquarters and shooting ranges for local civic guards, including the arquebusiers, with the name deriving from an arquebus, a type of an early musket known in Dutch as haakbus and in French as couleuvrine.

The painting itself must have been too large to be completed in Rembrandt’s atelier located in his still-existing house (modern address Jodenbreestraat 4, now known as the Rembrandt House Museum). There is a possibility that Rembrandt built a temporary “summer kitchen” at the back of his house.

According to the Rijksmuseum, Rembrandt was paid 1,600 guilders for his painting. At today’s exchange rate that would be around 726 euros, or 766 US dollars. But don’t worry, it wasn’t cheap – in those times, an outdoor laborer earned 6.50 guilders per week or just over 300 guilders per year. It was a small fortune.

The commissioners were happy with the unconventional painting and Rembrandt became a star. He continued to get commissions from the great and good. But after The Night Watch was finished, Rembrandt entered into a decade-long period where he stopped producing portraits and scaled back painting production dramatically.

Rembrandt’s success didn’t last forever. When he died aged 63 in 1669, he was buried in an unmarked grave, in a lot owned by the church. After 20 years, as was customary for those who had died in poverty, his remains were dug up and discarded. Why did it happen?

The artist was increasingly extravagant – he owned a grand house on Jodenbreestraat 4 and had a grand and very expensive fine-art collection. He was just spending too much and quickly became indebted. Also, some researchers see here problems in the artist’s private life – his beloved wife Saskia died in 1642, followed by their son, Titus, in 1668.

Group portraits representing militiamen had an established tradition in Dutch Golden Age painting. They were usually large in scale and portrayed the sitters in an unnatural and static manner. So what was so revolutionary in Rembrandt’s approach?

He was the first one to stage a group portrait as a history painting, the most prestigious genre of that time. The figures portrayed in The Night Watch are caught in motion, literally marching out of the canvas straight toward the spectator!

There were numerous theories as to who the unidentified girl in the background was. Was she Rembrandt’s late wife Saskia? Or was she an angel?

She must have been an essential aspect of the composition since Rembrandt decided to highlight her presence within the crowded composition. She is wearing a yellow dress and her entire figure seems to be glowing.

As we look closer, her presence proves to be indeed very important to the entire composition. Attached to her dress we can see a dead chicken with its claws raised to the sky, a bag of gunpowder and firearms – all symbols of the guild. Rembrandt thought of her as an imaginary mascot of the civic militia.

In the middle of the painting, behind a man in green and a guard with a metal helm, you can just about spot a man. Only his eye and a beret are visible, but this guy is believed to be Rembrandt himself. After all, it was not unusual for him to smuggle his self-portrait into his other famous works here and there.

Thanks to this 17th-century copy of The Night Watch, we know that the composition was originally larger. The monumental painting had to be cut down on three sides in order to fit in between two doors in its new location – the Amsterdam Town Hall where the work was moved in 1715. The strips of canvas that were cut away were not preserved.

On January 13, 1911, a down-and-out navy cook slashed The Night Watch with a knife, reportedly as a protest against his unemployment. A second knife attack occurred on September 14, 1975, this time courtesy of a Dutch schoolmaster who believed destroying it was his divine mission. After that, the painting was put under permanent guard. Nevertheless, an unemployed Dutchman sprayed concentrated sulfuric acid on the piece on April 6, 1990. Each time, restorations were able to repair the damage, with barely a battle scar remaining.

You can read more about attacks on famous artworks here!

It’s easy to think that a painting that hangs in the most honorable spot of the Rijksmuseum belongs to its collection, right? Well, you’re wrong! It officially belongs to the Amsterdam Museum, a museum documenting the history of the city of Amsterdam, but is placed on permanent loan to the Rijksmuseum.

This is obviously a pre-pandemic figure, but The Night Watch used to attract 2.2 million people a year – including every school pupil in the Netherlands, local Amsterdammers, and tourists.

In July 2019 the Rijksmuseum launched the largest research and restoration project ever for The Night Watch. This was happening live in the museum, and you can find more info about it here. The painting has been moved and is now back on view in the Gallery of Honour. Operation Night Watch started with the detailed study necessary to determine the best treatment plan and involved imaging techniques, high-resolution photography, and highly advanced computer analysis. The last time the painting was restored was in 1946–1947.

Here you can learn about the results of the research, and here you can admire every inch of The Night Watch in a supreme high resolution.

Below you can see a short video about the 1940s restoration of the painting:

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!