Skiing in Art History

Artists have long captured the magic of snow. During the 19th century, when winter sports like skiing, skating, and sledding became more popular in...

Louisa Mahoney 31 January 2024

A car might not be the most obvious topic for a painting, but as you can see, it appeared in various works throughout the years. It was a big inspiration for the Futurists, but not only! Discover the automobile in art.

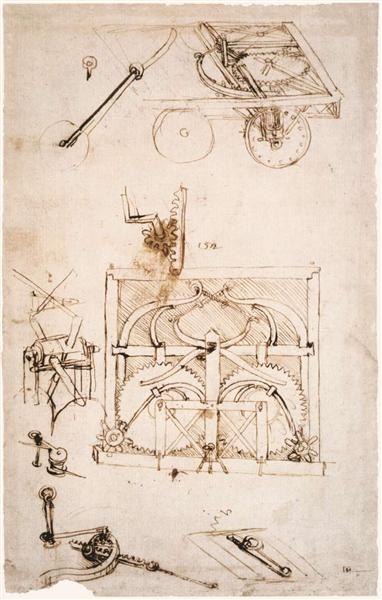

This drawing presents the original idea for the first self-propelled vehicle in history. Leonardo probably designed it for one of his patrons as a “showpiece”. Well, it definitely made an impression. If you’re curious about what it looked like, you can find a replica at the museum Clos Lucé, near Château d’Amboise, in France.

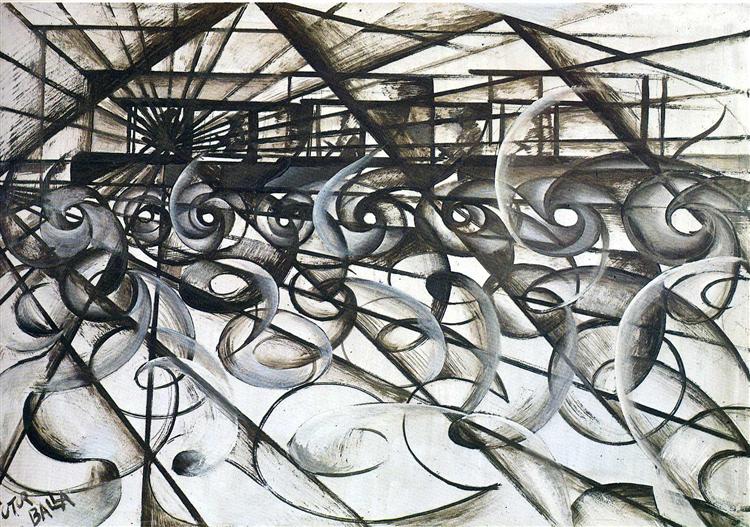

Point 4 in the 1909 Manifesto of Futurism by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti is devoted to cars.

We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath – a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Manifesto of Futurism, 1909.

Well, I was never convinced by this, but all the Futurists were. They dedicated many drawings and paintings to the study of movement and speed.

Around 1913, Balla turned to the studies of movement and, as a study case, he chose cars that had been manufactured in Italy only for a decade. In numerous studies for this work, he focused his attention on the landscape being altered “by the passage of a car through the atmosphere”1. Some suggest that this work is a central panel to a triptych.

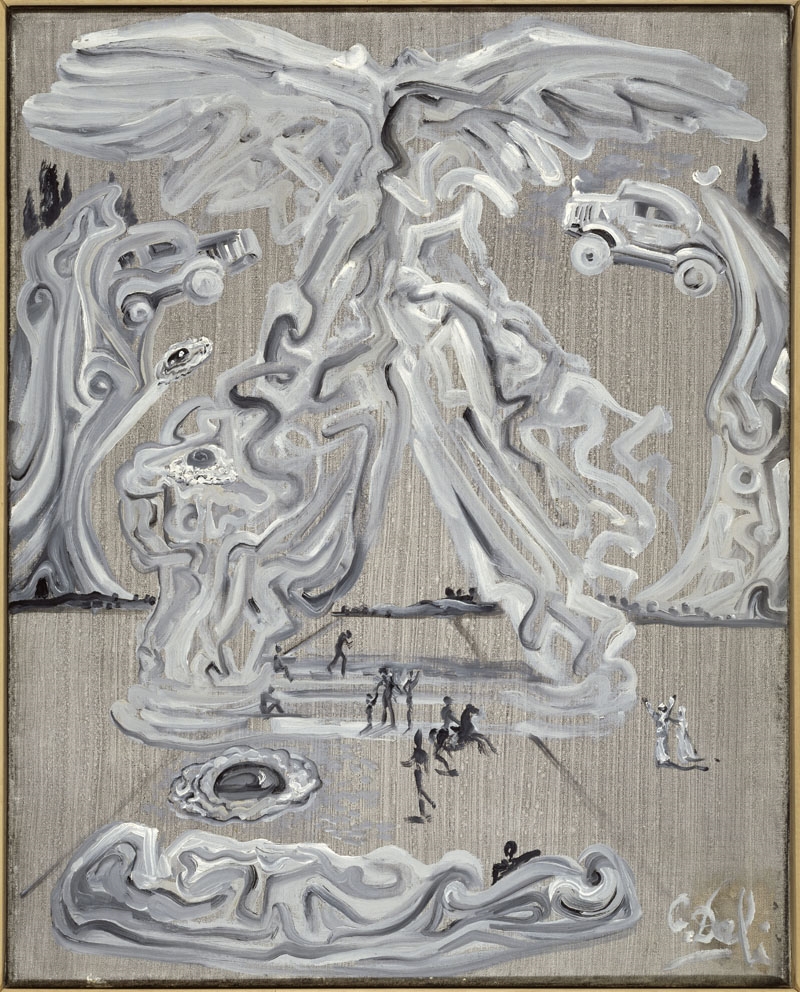

It was always Gala behind the wheel of the Cadillac because Dalí never got a driver’s license. Nevertheless, unlike most Surrealists, he often depicted cars, often imbuing them with meaning: here, by presenting a fossilized car and the rocks of Cap de Creus in Catalonia, he created a juxtaposition. Cars, a recent human invention that uses fossil fuel, are linked in a way to fossil materials, which are in turn immemorial in time. Tricky, isn’t it?

Here we have a Surrealist wink at Marinetti’s manifesto since Dalí presents Victory of Samothrace surrounded by two cars. Does he compare the beauty of the machine to the classical ideal? Or is it a parody of Futurists? And can we treat as the answer his 1929 note that “The most perfect and most precise metaphors come to us today coined and rendered objectively by the industry.”

Here it gets even trickier. Rauschenberg made a step further in the study of movement and especially artistic expression and authorship. As a provocative response to Abstract Expressionism, which was the most popular trend in the 1950s in the States, all about artistic license to express oneself, Rauschenberg made an expressive act/drawing/print/performance/installation piece (you name it). He asked his friend John Cage to drive a Ford in a straight line over 20 sheets of paper laid by him on the road outside his studio in Lower Manhattan. Was the work still Rauschenberg’s if he didn’t make it with his own hand? If yes, what makes one an artist in the automatized era?

Virginia Dortch Dorazio, Giacomo Balla: An Album of His Life and Work, New York: Wittenborn, 1969.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!