Five Contemporary Women Artists from Latin America You Need to Know

When we speak about contemporary art in Latin America, women artists are at the center stage. Working around various mediums and highlighting themes...

Natalia Tiberio 19 June 2023

19 June 2023 min Read

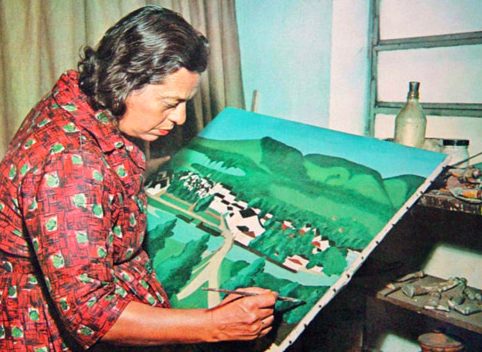

Djanira da Motta e Silva (1914-1979) was born in a very humble family, in Avare, São Paulo state in Brazil. She started to paint in her twenties when she was hospitalized due to tuberculosis. Before becoming an artist, she worked at a coffee plantation, then as a street vendor in São Paulo, and later as a pension manager in Rio de Janeiro. She created and owned a pension in the Santa Teresa barrio. This was a temporary home for immigrant artists and writers, who later on inspired her to pursue a career in art.

Djanira da Motta e Silva, more commonly known by her first name Djanira, was mostly self-taught, as she only received a very brief education in 1940 at the Liceu de Artes e Oficios. During her 40 years of creativity, she worked with many different mediums: oil, tempera, woodcut, drawings, engravings, ceramic tiles, and textiles. She illustrated books, designed mosaics, and painted murals. The last individual exhibition during her lifetime, organized in 1977 at Museu Nacional de Belas Artes in Rio de Janeiro, comprised over 200 works. The most recent show at MASP, designed by curators Isabella Rjeille and Rodrigo Moura, presented her 90 most celebrated works.

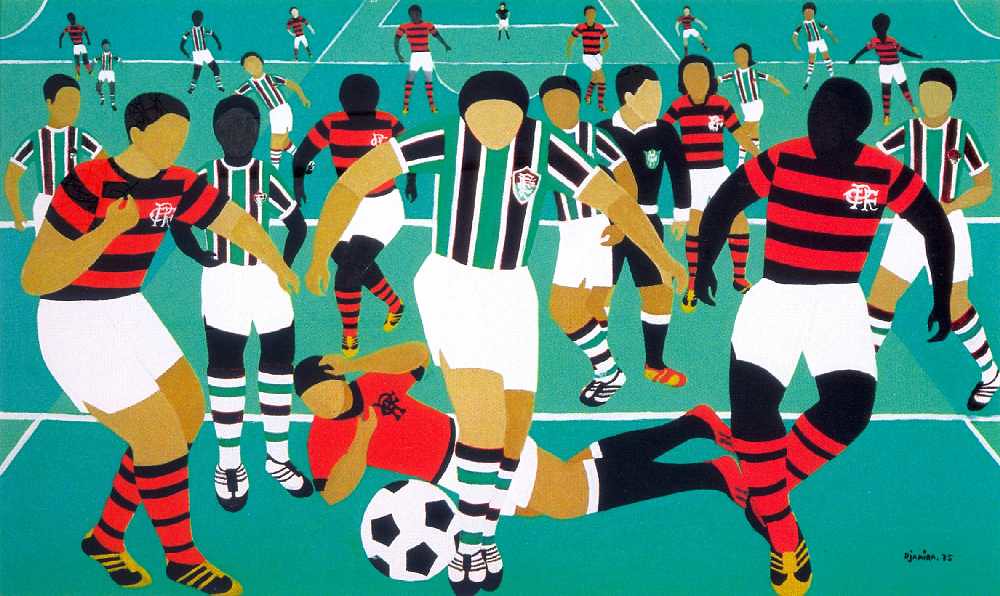

Her style was often branded as naive, primitive, and folkloric. Even though it was original and Brazilian in colors, topics, and sensibilities, we can see in it some inspiration from Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró, and Marc Chagall. It was her way of grasping the surrounding world in a country that went through dramatic transformations in the second half of the 20th century.

Contrary to these changes, Djanira’s works are immobile, flat, geometric, still, and resembling folk paper cuts. They are vibrant and bold, because of the colors used. They are reduced and distilled to the most basic elements of the natural forms. At the same time, the artist seems to be considerate and gentle with the subjects she portrays and immortalizes on the canvas. There are no caricatures and disfigurations in her vast body of work.

Djanira was always connected to her origins, touching on the regular, daily life of common Brazilians, their work, customs, and festivals. As she once said:

Everything I am, I owe to the people. I do not abandon my common roots as a woman and as an artist.

She was deeply religious and became a lay nun at the Third Order of Carmelites in 1963. She was also profoundly preoccupied with social justice, so she joined the Brazilian Communist Party and she visited the Soviet Union. Somehow, these two realities were not contradictory or exclusive for her. She explained it once:

Do not misunderstand me, I am for democracy, nationalism, and the self-determination of the people, and I am anti-imperialist, against any state intervention in culture, and I practice the Catholic faith.

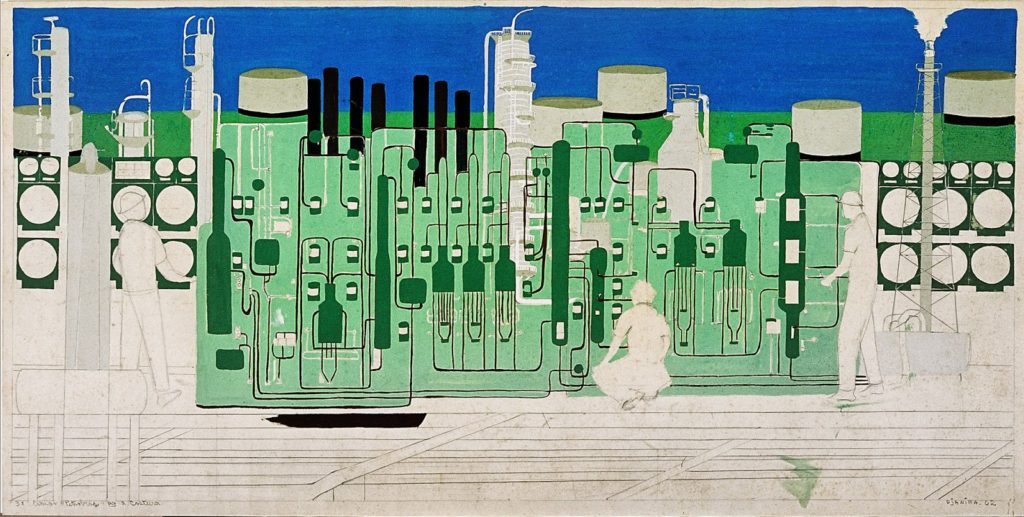

Many of her works depict religious themes, figures, and holidays, whilst others show industrial workers, factories, and mines.

In each work, Djanira offers a unique perspective on all things Brazilian. She gives us some snapshots of everyday life, joys, and the sorrows of mundane moments typical to the working class. She also documents the different ethnic customs of Afro-Brazilians and of Indigenous tribes. But in her art, we can also find a universal concern for the anonymous masses, people without unique facial features, without individual identities, defined by what they do and where they are in the social contexts and bigger structures.

Often the works of Djanira are populated by figures with no facial features. They do not have a specific identity or unique lives, no one can recognize them as their friend or family member. They are humans, but they are strange to us. We only see them as fishermen, footballers, and plant workers. We do not know what they think, feel, or perceive, just what they do.

For the brain, a face is like a puzzle. It always looks for the eyes and facial expressions for clues about emotions, personality traits, and character signs. By removing this, Djanira creates disturbing pictures of modern beings interlocked in social, repetitive interactions. They are distant, removed, placed by her to make a scene, and they are not its protagonist.

In the period of 1940-1979, when Djanira kept her art practice, Brazil passed through rapid industrialization and urbanization. The country transformed into a mass society, governed in non-democratic ways, by a dictator (Getúlio Vargas, 1937-1945) and military juntas (1964-1985). Djanira painted the new plants and their employees as well as still present and resistant to changes, as well as craftsmen, farmers, and plantation laborers.

She noticed the social and economic processes reconstructing communities in her motherland. She also depicted more human moments of leisure and rest typical to city life.

Djanira traveled extensively, visiting different regions of Brazil, and from her trips, she brought vivid memories of religious and ethnic customs. She translated them, sometimes in very psychedelic and atypical portraits of saints and deities, revered by Brazilians in their syncretic cults.

These works have anthropological meaning: They study the symbols, colors, and traditions of indigenous, African, and Portuguese cultural footprints and its impact on the diversity of modern Brazilian culture.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!