10 Romanesque Art Treasures from Barcelona

Barcelona = Gaudí, we all know that. For football fans, it is also the famous Barça, the team with the motto: “More than a club”. And so it is...

Joanna Kaszubowska 7 November 2024

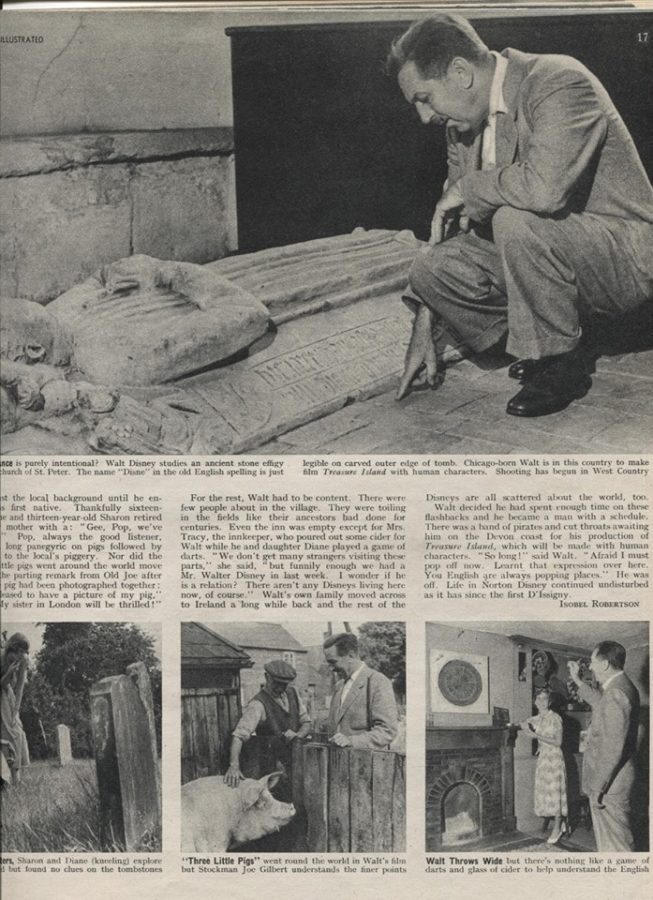

What do Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck have in common with a tiny village in Lincolnshire and the funerary art of medieval England? Say “Disney” and you get suspiciously close to “d’Isigny”. And there it is, the connection we are looking for.

When in the late 1940s, famous film producer Walt Disney ventured into England, he was hoping to prove his descent from a Norman invader of 1066, the soldier of fortune who came from Isigny near Bayeux to fight for William the Conqueror at Hastings. His descendants, the d’Isigny, are buried in the aforementioned village called Norton Disney and are said to have been Walt Disney’s forefathers. They rest in peace in the local parish church, one of the hundreds of inauspicious churches scattered across the English countryside. Their tomb effigies are modest compared to similar monuments England boasts.

For thousands of years, people all over the world placed great importance on burial rites and rituals. Britain has one of the richest histories of burial practices in Europe. They can be most revealing, varying from ceremonial burial inside of a cave, as in the case of the famous red ochre dusted Lady of Paviland, to an even more famous ship burial at Sutton Hoo. However, the greatest body of funerary monuments dates back to the Middle Ages, during which spectacular religious architecture was introduced, both on the Continent and in Britain.

Today in England, more than 150 military effigies survive from the thirteenth century and almost 200 from the fourteenth. In comparison to Continental Europe, England suffered few losses during World War II. London was the main target of the German invasion, but the English countryside, with its treasure chest full of history, remained virtually intact. Nowhere else in Europe can one accidentally stumble across a country church, only to find a knight resting in peace, immortalized in his splendid tomb effigy. The prominence of these knights vary–from history’s glittering figures, to common knights known only by name, such as Jock of Badsaddle buried in St Mary’s Church, Olingbury, Northamptonshire, who is said to have killed the last wolf (or boar) in England.

Armor effigies first emerged in Europe circa 1240 and gained most prominence on English soil. In contrast to the effigies of royalty, clergy and female aristocrats, the knightly ones show intense physical dynamism. Sword-pulling or cross-legged, the armored figures are far from lying serenely on their tomb slabs with their hands folded in prayer. Thus, such military effigies are identifiable not only by chain mail and surcoats, shields and swords, but also vitality.

Components of their costumes denote the figures’ knightly status, as in the case of the famous William Longespee’s tomb effigy in Salisbury Cathedral. The effigies shown in the photos depict the knights from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Another interesting example is Sir John de Lyons of St Mary’s Church, Warkworth, Northamptonshire, who is literally covered with lions. Lions are everywhere. They adorn his armor, his helmet, his sword, and his shield.

Another group of tomb effigies is exceptional in a different respect. Sir Ralph Greene (d. 1417) and his wife Katharine were buried in St Peter’s Church, Lowick, Northamptonshire. Their tomb is unusual in that Ralph is holding Katharine’s hand. There are only a few monuments in England of this form (including the famous Arundel Tomb), and even fewer on the Continent. In medieval art, when a couple was shown holding their right hands, as in case of Sir Ralph and Lady Katharine, it meant their union was sanctioned by God, and they were married. When, however, a couple was holding their left hands the message was clear – their love was an adulterous one. Ralph and Katharine rest together as man and wife, in perfect union, even after death. On more down-to-earth note, note the details of his armor and her splendid headdress.

One of the finest tombs in the country can be found in St Mary and St Barlock’s Church in the village of Norbury, Derbyshire. They were made for the family of John Fitzherbert. They are in Chellaston alabaster from Nottingham School. Originally richly decorated and colored and carved with great care and delightful detail, they date from about 1491.

The most refined monuments were made of alabaster, but a new trend was to emerge. Smaller, two-dimensional effigies made of brass affixed to monumental slabs of stone were introduced. Since they were cheaper, they won great popularity among the emerging middle class. One of the finest examples can be found in St at Broughton, Northamptonshire, where Lady Philippa Byschoppesdon was buried. She was one of the five daughters and two sons of Sir William Wilcotes of North Leigh and Headington, who represented Oxfordshire in Parliament and was appointed chief steward of the estates of Richard II’s queen, Anne of Bohemia. Philippa’s grandson, William Catesby, closely connected with Richard III, was the Cat commemorated on the well-known satire on the favorite ministers of the king which began: “The Cat, the rat and Lovel our dog do rule all England under the hog”. He was beheaded after the battle of Bosworth in 1485. Lady Philippa’s brass effigy is one of the finest in the country.

Another famous brass effigy has been preserved in St Margaret’s Church in Felbrigg, Norfolk. It shows Sir Simon Felbrigg and his wife Margaret, the duchess of Cieszyn [Teschen], today’s Poland. Lady Margaret came to England as one of the maids of honor to the future queen, Anne of Bohemia. King Richard II saw fit to arrange her marriage with his standard-bearer. Lady Margaret and Sir Simon married and had three daughters together. She predeceased her husband and was buried in the aforementioned church in her husband’s family estates. Sir Simon commissioned their joint effigy. He was to be buried next to her, but remarried and was buried with his second wife in the choir of the Norwich Blackfriar’s church. The tomb inscription is in Latin. Blanks were left for Sir Simon to be filled in upon his death, however they never were due to the aforementioned circumstances. The effigy is full of royal symbols of Richard II. His arms appear on the left shield at the top, next to another shield with the arms of his queen, Anne of Bohemia. Below these, is the shield with the arms of Sir Simon and his wife Margaret, her half being the arms of her father, Przemysław I, the Duke of Teschen. Below these again is the Felbrigg badge of a fetterlock, used twice. Below the shields is Richard II’s person badge of the white hart. Sir Simon himself is shown carrying the personal standard of Richard II. Just below his left knee he wears the Order of the Garter. The inscription on the tomb reads:

“Here lie Simon Felbrigg, knight, former Standard bearer to the most illustrious lord, our lord the King Richard the Second. He died on the …day of the month of … in the year of our Lord 14.. and the lady Margaret formerly his wife, of the nation and noble blood of Bohemia and formerly maid of honour to the most noble lady Anne, Queen of England; she died on the 27th day of June in the year of our Lord 1416; upon whose souls may God have mercy; Amen.”

Inscription on the tomb of Sir Simon Felbrigg with his wife Lady Margaret, St Margaret’s Church in Felbrigg, Norfolk, UK.

Author’s bio

Katarzyna Ogrodnik-Fujcik is a teacher, medievalist and freelance writer. She works with different magazines and websites on Polish and European history. She runs a blog dedicated to Henry the Young King.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!