Rembrandt’s Light exhibition at The Dulwich Picture Gallery celebrates the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death. The focus of this exhibition is on the artist’s use of light. It may seem like a limited and even narrow perspective with an artist as complex as Rembrandt, but what makes it a success is that it cuts out all the “noise” — allowing the viewer to consider Rembrandt’s Light from all angles.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606–1669) was a Dutch draughtsman, painter, and printmaker. An important artist from the Dutch Golden Age, he is considered one of the most significant and influential in history. This exhibition focuses on the period from 1639 to 1658. At this time, Rembrandt lived at his house on the Van Breestraat in Amsterdam. His studio in the house was full of light, and Rembrandt arranged it to control and take full advantage of that.

The exhibition lighting and design have been carefully curated to give justice to the master’s use of light. Dulwich Picture Gallery in-house curators, Jennifer Scott and Helen Hillyard, collaborated with the award-winning cinematographer Peter Suschitzky to make this happen.

Each room includes a few paragraphs to set the stage for visitors, which is not an uncommon setup. What is unusual, though, is the room lighting notes. Showing visitors that the use of light to create and evoke emotions is a conscious effort, not an accident. Much as people react to light instinctively and subconsciously, here it is used to lead visitors. They are taken on a journey from the most striking and dramatic effects, through meditative moods, all the way to intimacy.

Dramatic Stage

The first room is a striking contrast to the colorful and cheerful space that is left behind to enter the exhibition. It contains dark blue walls, dimmed lighting, and striking spots of light, focusing attention on the paintings. The world truly becomes a stage—the curators echo the dramatic and bold use of light in Rembrandt’s paintings.

The historical paintings in this room rely on light to guide the viewer. The key aspects and figures are drawn from the darkness by powerful spotlight-like lighting. That is when Rembrandt’s subtlety shows, as he slowly extinguishes the light when spectator’s eyes move away from the focal point. It is as if he is giving time for the viewers eyes to adjust and explore all the details hidden in the semi-darkness. The painting visible from the entrance is The Denial of St. Peter, but I found the smaller and darker Philemon and Baucis more evocative.

Day in the Studio

As if to prove how easily lighting affects perspective, the curators set up the second room as a bright one in comparison. Giving insight into Rembrandt’s studio and his teaching process, but also shocking one out of the respite of selective focus granted by the darkness of the first room, it brings visitors back to the real, hard-working world. This room shows the setup Rembrandt used to control the light coming through the big windows in his studio; it also shows how he shared his knowledge with his students and how they practiced their skills.

Night

Moving into the night again, the next room highlights the only surviving night landscape by Rembrandt–The Landscape with the Rest on the Flight into Egypt. It beautifully showcases his mastery in the use of color to evoke light, shade, and darkness. They almost have a haptic quality to them, texturally.

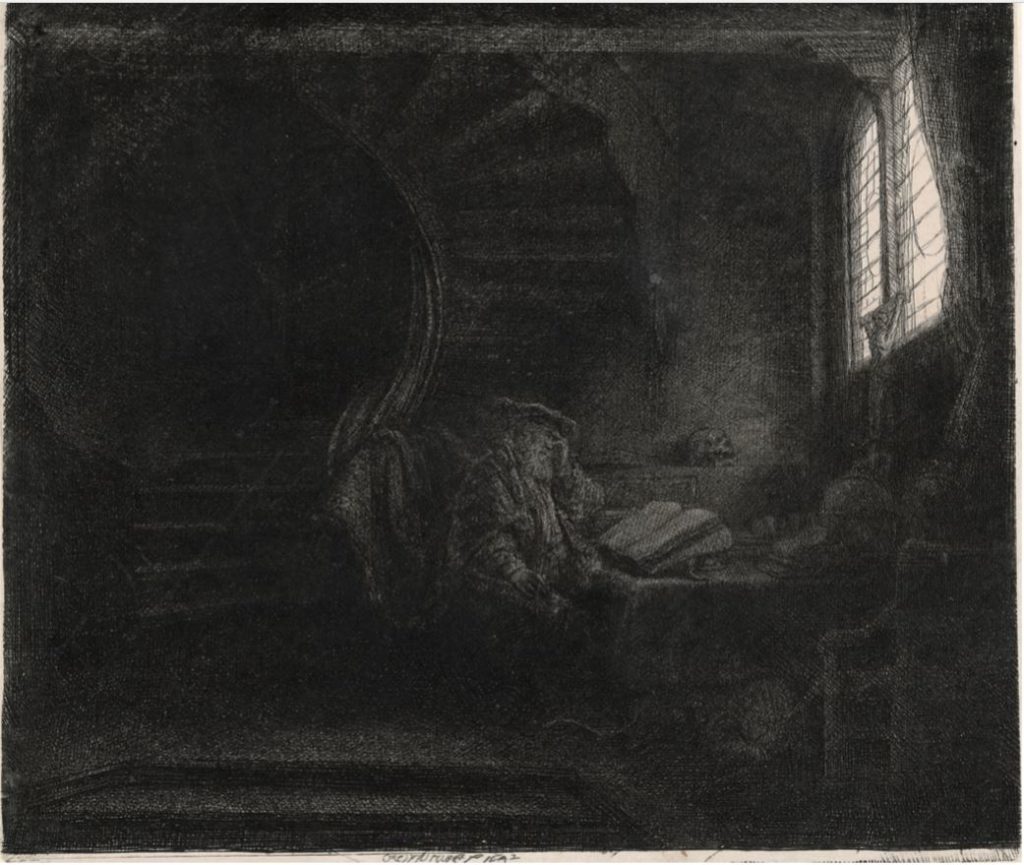

The mausoleum is candlelit and flooded with a warm yellow glow, continuing the light-dark pattern. Etchings and drawings prove Rembrandt’s skill in picturing darkness, full of detail gently outlined by a single source of light (e.g. a candle). Rembrandt shows the life of light and how it reaches its limits, overcome by darkness. For example, St. Jerome in a Dark Chamber initially seems almost entirely black, until the viewer’s eyes adjust and can make out the details bathed in the dispersed light coming through a blindingly bright window at the edge of the frame.

Experience

Nearing the exhibition climax, visitors enter a room with a single painting on display – Christ, and St. Mary Magdalene at the Tomb. Do not rush through it; spend a few minutes there leaning on a conveniently placed parapet and observe. The curator’s skill and experience truly show here— they add a time aspect to an exhibition about light, and it changes everything. As the light gradually dims and brightens again, the perception of the painting changes, from full of color to monochromatic and back. As it happens, the viewer may start to notice different things, that otherwise would go unobserved.

What this room also does is force visitors into introspection on how they perceive light. Attention is not only on the painting now but also on the individual observing the painting and their feelings. All the reactions that in the previous room were subconscious come to the fore here. The pieces of the puzzle shift and slot into place, and suddenly it is clear just how powerful light is when perceiving the world. It demonstrates how vulnerable to manipulation by both artists and curators a person’s instinctive reactions to it makes them. This is the point where, personally, this exhibition changed from a show into an experience.

Can It Get Any Better?

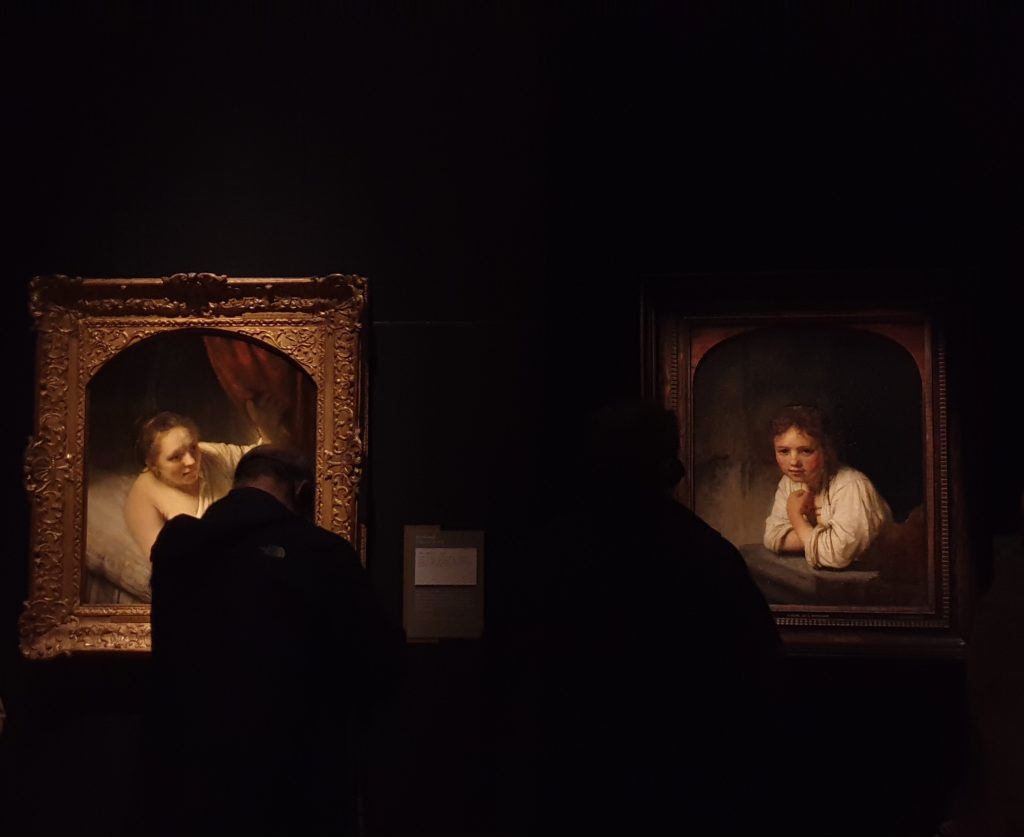

Yet all this was just preparation for the final room; the room has black walls, including Stuart Semple’s Black 3.0 paint (the world’s blackest acrylic paint, with an interesting side-story you can read here) and is full of portraits. The people depicted are almost reaching out to the viewer, their bodies glowing and bathed in warm light. Each painting becomes a window with a person beckoning.

The trio of Woman in Bed, Girl at a Window, and A Woman Bathing in a Stream urging one to come closer, as the attentive Young Man, perhaps the Artist’s Son Titus watches. To finish it all, Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait with a Flat Cap, in which the observer cannot mistake the look of self-satisfaction, maybe even a certain smugness from the artist who pulled it all off, leaves visitors shaken. With an oeuvre so complex that it warrants an exhibition focused solely on light to allow the space needed to understand it, why wouldn’t Rembrandt be proud?

Exhibition trailer:

15 Things You May Not Know About The Night Watch by Rembrandt

A New Rembrandt Painting Discovered

Nine Reasons to Smile with Frans Hals

Rembrandt’s Light – Dulwich Picture Gallery

4 October 2019 – 2 February 2020

Prices:

Friends and under 18s: Free

Standard Admission: £ 16.50*

Concessions: £ 8.0*

Under 30s: £ 5.0 (sign up required)

*Ticket includes an optional gift aid donation.