The Wallace Collection displays a collection, which came together in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, collected by the first four Marquesses of Hertford. One piece, living in the beautiful collection, is The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. The Rococo oil painting came to life between 1767-1768 and depicts a French lady playing on, yes, a swing. She’s swinging so joyously that her dainty pink shoe is flying off. Behind and below her (the shock) two French gentlemen also enjoy the scene – a sensual love triangle in sumptuous Rococo style.

History of the Wallace Collection

Sir Richard Wallace, the son of the fourth Marquess*, was the last to continue building up the collection. Upon his death, his wife gave Hertford house, and everything in it, to the nation (1897) – what a gift!

“Shall be kept together unmixed with other objects of art.”

The bequeath of Lady Wallace.

For years the above line was taken to mean that all the pieces should stay together and never leave Manchester Square, not even on loan for exhibitions. However, the ban on loans is not explicit, and Sir Richard himself had often lent objects to other museums. So, the Wallace Collection does now allow temporary loans, in order that they may share their art with the widest possible audience.

The Collection, across 30 gorgeous rooms in Hertford house, includes art-works from 15th to the 19th centuries; including: furniture, weapons, arms, porcelain and Old Master paintings (anything by a painter of skill who worked in Europe before about 1800). You can read about the history of the collection in this excellent piece.

*What is a Marquess?

A Marquess (or Marchioness) is a hereditary aristocratic title for a nobleman ranking above an earl and below a duke. The honorific prefix “The Most Honourable” precedes the name of a marquess or marchioness of the United Kingdom.

A Beautiful Boudoir Painting

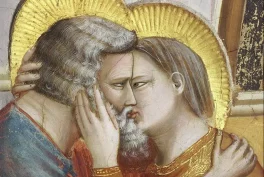

The Swing is Fragonard’s best known work, a masterpiece in the Rococo style. It shows not just the woman on the swing but also two men, seemingly unaware of each other. In the foreground is a man lying on the ground, looking upwards at the swing, and in the background is a smiling older man, who is pushing the swing. In front of the older man there is also a small barking dog. The other presences in the scene are two statues: a putto (a chubby male child, usually naked and sometimes winged) and another pair of putti in the background. As you can probably guess, this is a scene of an affair.

Set in an outside grove bounces off the idea of a “boudoir” (bedroom) painting – an image of a woman in her private chambers. The decision to situate the scene in an overgrown garden looks forward to the impending Romantic era’s emphasis on nature. It also allows the woman to take control of the picture. And take control she certainly does. Her billowing, ruffled, ballet-pink dress, floats in a dramatically lit clearing. Her delicate shoe, flying through the air, gets a spotlight. The painting is an excellent example of the exuberance and elegance of Rococo art.

A Masterpiece of the Rococo Era

Fragonard painted over 550 paintings in the Rococo style. But what is Rococo?

Rococo style (also known as Late Baroque) began in 1730s France as a reaction against the more formal style known as rocaille style, and soon spread across Europe. It reflects the taste of French aristocracy at the time, and later 18th century English art collectors too. The idea was to have these paintings hanging as dreamy backdrops for the pageantries of court. society. During this period, rooms became smaller and the paintings were conversational – encouraging viewers to come up close and look at details. The Swing is only 81 x 64.2 cm!

Rococo is exceptionally ornate and theatrical but does eschew the grandeur of the previous Baroque fashion. Rococo works combine asymmetry, curves and pastel colors to create the illusion of motion and drama; all things which Fragonard’s painting does masterfully. It’s a sparkling dream-world.

The Scandalous Commission

So, the story in and of the painting: The Baron Louis-Guillaume Baillet de Saint-Julien was a French aristocrat, and like all the 18th century French aristocrats he had a mistress. Again, like lots of the French elite at the time, he wanted a picture of his mistress. However, he wanted a picture with him looking up her skirt. In the request he also specifically asked for her ankles to be on show. Commissioning such a blatantly erotic painting (yes, ankles!) of your mistress was not a norm.

This was so scandalous that the first painter Gabriel François Doyen, refused (according to the memoirs of the dramatist Charles Collé). Doyen’s refusal was lucky for Fragonard, who, off the back of The Swing’s success, made a break from history painting.

Fragonard certainly had fun with the piece. The Cupid on the left-side gestures to keep the secret. He is a playful reference to another affair induced commission. Already famous in the 18th century the piece is l’amour menaçant (menacing love): a statue for Madame de Pompadour, King Louis XV’s art-loving mistress.

The Happy Accidents of the Swing and Power Play

The Happy Accidents of the Swing (Les Hasards heureux de l’escarpolette) is the painting’s original title, but, as we have read, the naughtiness of the painting was no accident! Some would go as far to say that the poem’s composition is a little bit radical:

“A disguised representation of inverted sexual intercourse.”

Clive Hart and Kay Stevenson Call, Heaven and the Flesh: Imagery of Desire from the Renaissance to the Rococo, 2008, Cambridge University Press.

By “inverted” the art scholars mean that the woman is on top. The mistress is swinging back and forth, while her lover passively gazes in adoration and extends a very euphemistic arm. If that’s too much of a scholarly stretch it’s not hard, at least, to admit that swinging does at least put the fully-clothed female in the power position in the painting, which is not something we see every-day in art history.

“The lady is sat on the Swing precariously balanced between two people. Women at the time did not have much power in terms of money and lands (that went from father to husband if there was any). But they did have influence and they had to use their wiles and natural beauty to gain a position in Court. So she might hold the power and beauty at the moment, but the precarious swing position shows us that it might not last.”

Curatorial Assistant at the Hogarth collection, Carmen Holdsworth-Delgado, December 2013, last accessed 10/11/2019.

More Power Play with Yinka Shonibare

For some more power-play inspired by The Swing you could consider Yinka Shonibare’s installation (2001). The British-Nigerian artist positions a dark-skinned mannequin clothed in the Dutch wax print playing the role of lady on the swing. A Daily Art article about this piece will soon be available.

You can also read more about The Swing here, focusing on themes of money, power and sex.

A Final Swing with Fragonard

This massive canvas (215.9 x 185.5 cm) reminds us that Fragonard was not just a masterful Rococo painter but also created incredible landscape paintings. What’s fun, is that this huge landscape The Swing has shared features with our delicate Rococo The Swing. Not least the scene itself, but also the bubbling fountains, sculptures, and overgrown flower beds. You can read in more detail about this piece here.