Madness in Art: A Powerful Connection

Madness and art have long shared a profound and powerful connection, where the boundaries between genius and instability often blur. Many acclaimed...

Maya M. Tola 28 October 2024

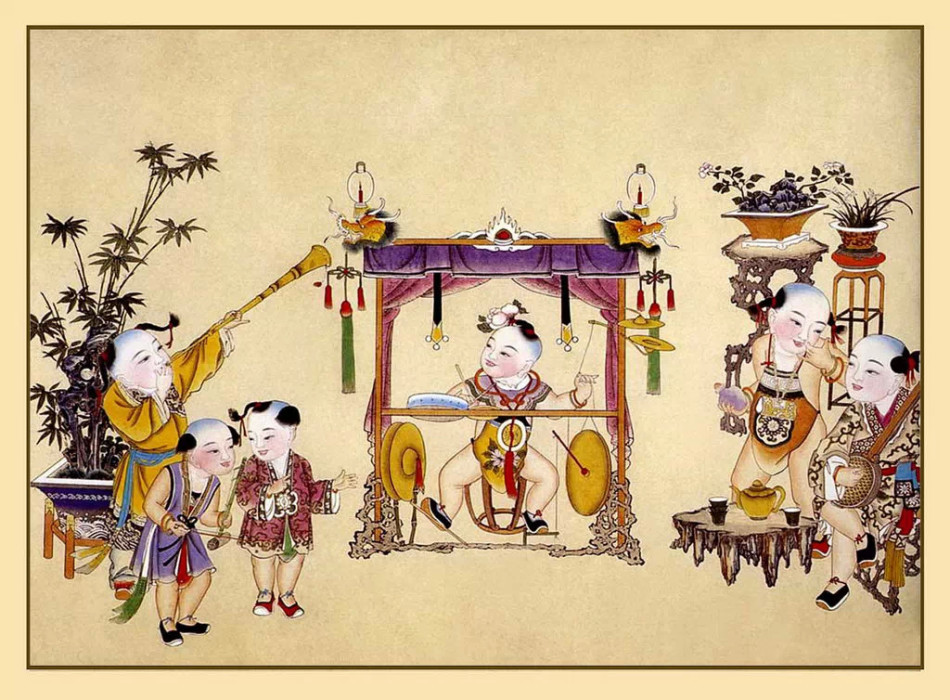

Imagine a household celebrating the Chinese New Year where children share a home and joyfully play together. They have different kinds of toys to play with; two children play with a puppet hanging from a pole, like out of a famous fairy tale. The elders sit solemnly in the main hall. In the building behind, women are busily preparing the New Year’s dinner. A fresh aroma of pine tree branches fills the air.

Yao Wen-han, an 18th century Chinese artist, depicted the scene described above in his Joyous Celebration at the New Year. The setting looks somewhat familiar. However, not only did Chinese people keep this tradition throughout many centuries, they also came up with unique ways of celebrating. As a result, they created the most beautiful art for the Chinese New Year.

Chinese New Year, also called the Spring Festival or Lunar New Year, falls between January 21st and February 20th annually. Although spring has yet to come, Chinese people begin preparing for its arrival. Celebrations traditionally last for half a month starting on Spring Festival Eve, and culminating with the Lantern Festival. In 2025, January 29 initiated the Year of the Wood Snake.

In China both the Gregorian and Lunar calendars are used. The Spring Festival refers to the Chinese New Year to differentiate between the two. Yuandan has become the term for the first day of January or the Gregorian New Year. Families celebrate it as a one-day holiday in China. Yuandan traditions include the making of New Year’s resolutions, such as trying to lose weight or quit smoking.

Lunar New Year is filled with many interesting traditions. For many people, it is a time to honor deities and ancestors. Before the celebration starts, families clean their houses to make way for incoming good luck. On New Year’s Day, everybody dresses up in their best clothes. Children get hongbao, a small red envelope with gift money from their parents, grandparents, and older relatives. To create a happy and prosperous atmosphere, Chinese people write couplets on red paper and paste them on either side of the front door, put flowers in windows, and hang colored New Year pictures and red lanterns.

On New Year’s Eve, families gather for an annual reunion dinner. Around midnight many people in northern China enjoy eating jiaozi, or dumplings. These symbolize wealth because their shape resembles a Chinese sycee, which was a type of gold and silver ingot currency used in China under the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). Southerners, however, eat niangao, the New Year cake made of glutinous rice flour. Eating this cake can signify progress and promotion at work, and improvement in life year by year.

The tradition of celebrating Chinese New Year started with the story of Nian. He was a legendary mythical beast that lived under the sea or in the mountains. Since food is sparse during winter, Nian would go to a nearby village. There he would eat the crops and sometimes villagers, mostly young children.

One year all the villagers decided to hide from the beast. However, Yanhuang, a brave old man, said that he would stay the night to take revenge on Nian. All the villagers thought he was insane but the old man put red papers up and set off firecrackers. When the villagers came back to the town they saw that Nian had not destroyed anything. They assumed that the old man was a deity who had come to save them. The villagers realized that Nian was afraid of the color red and loud noises. Therefore, red represents joy and is the predominant color for New Year celebrations, it symbolizes virtue, truth, and sincerity.

Since then, when New Year was approaching, the villagers would wear red clothes, hang red lanterns, and red scrolls on windows and doors, and use firecrackers to frighten away Nian. Nian resembled a flat-faced lion with a dog’s body and prominent incisor. In modern times, some families invite a lion dance troupe as a symbolic ritual to meet the New Year. In Chinese, the word nian means “year.”

As well as for the villagers, the legend and meaning of Nian became important for court officials. That is probably why they gave this beast a prominent place on their robes. A robe revealed a wearer’s rank. For example, a blue robe indicated that the wearer was a minor prince, nobleman, or official.

At New Year celebrations noblemen usually displayed ancestor portraits for worship at home. The ancestor portrait of a Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) noblewoman reveals how the painter conveyed a sense of status through the sitter’s dress. Her blue coat has a mandarin square, a large embroidered rank badge, sewn onto the coat. It was embroidered with a detailed, colorful lion insignia indicating her rank. Mandarin squares were first authorized for wear in 1391 by the Ming Dynasty. The noblewoman probably inherited this mark of rank from her father since women were not eligible to hold government office at that time.

It was possible to see this ancestor portrait and other artworks at the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands. Their splendid exhibition, Pearls From the Far East, was on view until October 2020. This exhibition also contained other objects from the collection of the museum’s founder, Helene Kröller-Müller, who had a passion for Chinese art. In addition to early ceramics, this rarely displayed but extremely varied collection included small sculptures in bronze and different types of stone, such as jade, and soapstone, as well as a substantial collection of paintings and works on paper.

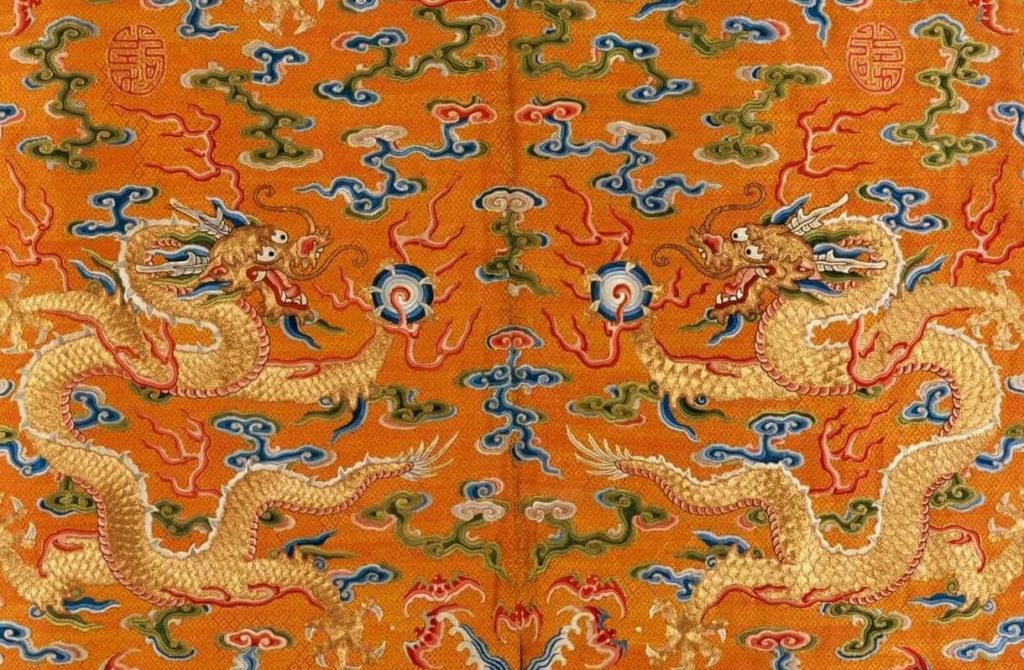

In the past, emperors also celebrated the Lunar New Year and wore a festival robe for this special occasion. Dragons are symbolic in Chinese culture and people believe that dragons can bring good luck. Dragons possess great power, dignity, fertility, wisdom, and auspiciousness. A dragon, chosen as an emblem of imperial authority, is both fearsome and bold but also has a benevolent disposition.

Only the emperor, his consorts, or the crown prince could wear a “dragon robe”. Chinese craftsmen usually decorated this kind of robe with powerful, vibrant, and fierce five-clawed dragons and other symbols of prosperity. These markings represented the emperor’s control over all elements of the universe.

Although people could not wear the dragon robe, they could still perform the dragon dance in the streets of their towns. Each holding a part of the dragon on poles, a team of performers carries the “dragon” along its route. Usually, this dragon stops at people’s doors and nods its head up and down, then performs a few rhythmic movements to wish the inhabitants of the house a happy New Year. In response, the master of the house lets off fireworks and gives the performers a suitable gift. Failing to do so risks suffering the consequences of angering the dragon.

Lunar New Year traditions also incorporate symbolic elements with a deeper meaning. One common example of Chinese New Year symbols is the fu characters, meaning “happiness”, “fortune”, or “good luck”. People display red diagonal signs with these characters, upside-down, at the entrances of their homes. This tradition dates back to the Song Dynasty (960–1279). In Chinese, the phrase “upside-down fu” sounds almost identical to the phrase “good luck arrives”. It signifies a wish for prosperity to descend upon a dwelling.

In addition to diagonal signs, the fu character can also appear in many different objects, not necessarily red. For example, during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor (1654–1722), Chinese artists made famille verte wine pots in the form of the characters fu and shou. The word shou means “long life”. Famille verte is a type of Chinese porcelain which is predominantly green in color. The iridescence of this type of porcelain is most visible in the blue and green enamels due to the glaze has contracting. The novels The Three Kingdoms or the Romance of the Western Chamber were likely a source of inspiration for the illustrations on these pots.

You can see porcelain, embroidery, calligraphy, silk, jade, and other precious items from nearly 4,000 years of Chinese imperial culture at the Tullie House Museum & Art Gallery in the United Kingdom.

On the 15th day of the first month of the year, many Asians celebrate the Lantern Festival. Families light candles outside their houses and walk the street carrying lanterns to help guide wayward spirits home. By releasing sky lanterns into the air, people let go of their past selves and get new ones, which they will then let go of the following year. To light up the atmosphere, families usually display red couplets and lanterns on their door frames.

The Lantern Festival tradition may have been started by the Han dynasty emperor, Ming (58–75 CE). Inspired by the Buddhist practice, Emperor Ming ordered all households, temples, and the imperial palace to light lanterns on the 15th day of the first lunar month. In the past, the lanterns were fairly simple, and only the emperor and noblemen had large ornate ones.

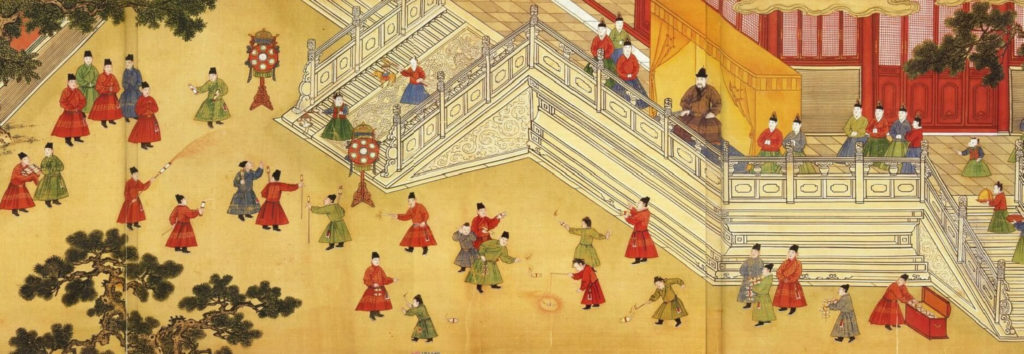

Successive Chinese emperors liked this practice and continued to celebrate the Lantern Festival. In 1485 an imperial court painter depicted the Chenghua Emperor enjoying the festivities with families during the Lantern Festival. Activities included acrobatic performances, operas, magic shows, and setting off firecrackers. Also, to create small explosions, courtiers filled bamboo stems with gunpowder that was subsequently burnt.

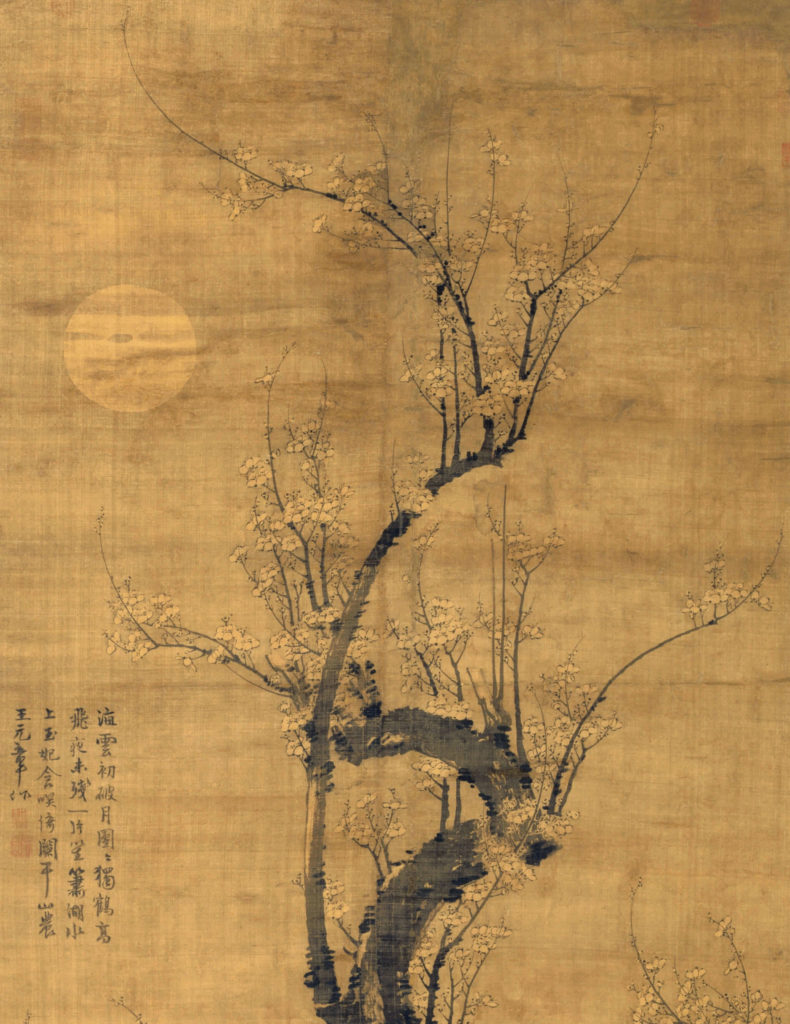

After the celebrations came to an end, the Chenghua Emperor would observe plums blooming in the early spring and resisting frosts. Therefore, plums came to symbolize endurance in adverse times. During the Spring Festival, he might look at a scroll with plum blossoms, similar to Wang Mian’s A Prunus in the Moonlight. This painting is a masterpiece of brushwork and composition. The artist shows a magnificent plum tree under the full moon. Wang Mian’s sweeping brushstrokes left traces of so-called “flying white on the branches” that appear as reflections of the bright moonlight.

In the past, Chinese artists began to count the long chilly days by coloring a painting day by day. For example, the court painter would sketch a branch of plum blossoms with 81 petals in total. From then on, he would color one petal each day and the coloring of the last petal marked the arrival of spring.

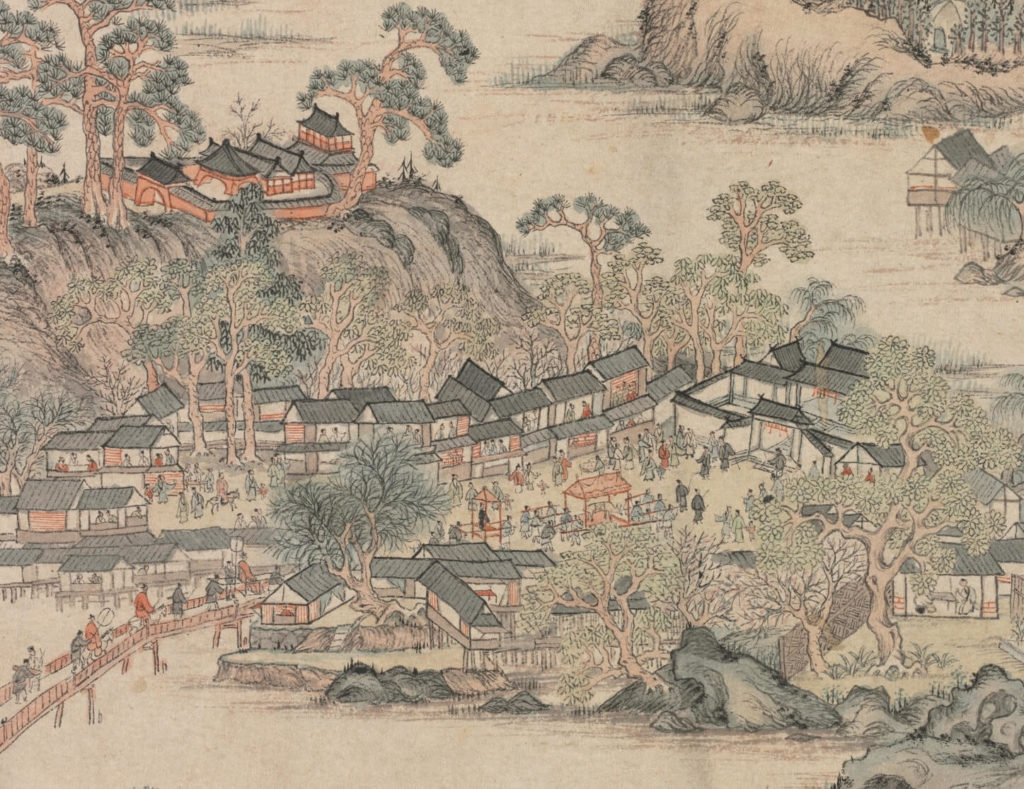

In contrast to the sumptuous palace of the Chenghua Emperor, the settings of the water-rich Jiangnan region in southeast China were very different. Nevertheless, Wu Bin masterfully portrayed the landscape in his painting Greeting the Spring. The light colors and delicate brushwork accentuate the image of Chinese New Year festivities. Scenes of celebration and performing on the streets are interspersed with the activities of farming, fishing, and making silk. In the middle ground, the villagers lead an ox made of clay under a canopy in a procession. Chinese people call this ceremony “whipping the spring ox” and it is performed in the hope of a good harvest.

An ox made of clay was important for Chinese people as it was part of the Chinese zodiac. The zodiac is part of a 60-year cycle that employs animals, five colors, and two sets of symbols: the “Ten Heavenly Stems” and “Twelve Earthly Branches.” Chinese people associate each animal with one branch, and each color correlates to two stems.

Japanese artists produced ukiyo-e using woodblock printing, a technique originated in China. The earliest surviving examples of woodblock printing date back to 220 CE. This method helped to spread Buddhist classics and novel illustrations among the first public works.

A New Year picture is a popular banhua in China. Banhua is the Chinese term for any printed art objects, especially woodblock prints. Originally the banhua was a picture of a door god, a divine guardian of doors and gates. People believed that the door god could protect them against evil influences and encourage the entrance of positive ones.

Later people included more subjects such as fairs, the kitchen god, dancers, women, and babies. These pictures served as a decorations during the Spring Festival and were believed to bring good luck in the coming year. When New Year arrives every family replaces its New Year picture. This way they say goodbye to the past and welcome the future.

Traditional New Year pictures or cards have simple, clear lines, brilliant colors, and scenes of prosperity. The development of New Year’s pictures reached a peak in the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Wuqiang County, Hebei Province, is one of the five places famed for their production. The four others are Yangliuqing in Tianjin, Taohuawu in Jiangsu, Weifang in Shandong, and Mianzhu in Sichuan. Prints of New Year pictures became popular in the 17th century.

Among the most famous production places is Yangliuqing, located in the suburbs of Tianjin in northern China. For more than 400 years, it has specialized in the creation of these woodcuts for the New Year. The Yangliuqing style has vivid color schemes used for traditional scenes of children’s games. These scenes were often interwoven with auspicious objects.

We live in a global world where everybody is connected. Influenced by the traditions of other countries, we as humans share an international cultural heritage. Not only is China celebrating the Spring Festival but also Chinese New Year festivities are held around the globe. People have lavish celebrations featuring spectacular winding dragon or lion dances. Revelers hope to usher in a year of increased prosperity and good health.

Regardless of how or where people celebrate this holiday, the New Year is an opportunity to get a new lease on life. Lunar New Year or Spring Festival is a time to reconnect with family, share gifts, eat, drink, and enjoy the possibilities that the new year will bring!

Happy New Year!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!