Blood in (and as) Art

One of the first known expressions of human creativity, the Lascaux cave paintings, were created with blood, a material that has remained significant...

Kaena Daeppen 10 June 2024

Many people are obsessed with cute cats, penguins, pandas, koalas, and all sorts of animals. However one rarely hears about the wombat, especially in relation to art. It seems the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was very unique in its wombat-craze. Wombats are cute and they also deserve some of our attention. So, let’s see why the Pre-Raphaelites loved the wombats.

Wombats are short-legged, muscular marsupials that are native to Australia. They are about 1 m long with small, stubby tails and weigh between 20 and 35 kg. They dig extensive burrow systems with their rodent-like front teeth and powerful claws. One distinctive adaptation of wombats is their backward pouch. The advantage of a backward-facing pouch is that when digging the wombat does not gather soil in its pouch over its young.

Wombats have an extraordinarily slow metabolism. It takes around 8 to 14 days to complete digestion, which aids in their survival in arid conditions. They generally move slowly. When threatened however, they can reach up to 40 km/h and maintain that speed for 150 meters. A group of wombats is known as a wisdom, a mob, or a colony.

From about 1803, a steady trickle of live wombats reached Europe. We know there was a wombat among the birds and animals that were delivered to the menagerie of the Empress Joséphine Bonaparte at Malmaison, near Paris. Another early wombat owner was the English naturalist Everard Home. His paper on the subject, ‘An Account of Some Peculiarities in the Anatomical Structure of the Wombat,’ appeared in March 1809 in the Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, and the Arts.

The illustration above may be a bit misleading. When drawing the sketch William Bell Scott was convinced that the creature he was drawing was indeed a wombat. However, Angus Trumble believes this specific animal is a woodchuck (groundhog). The size of the animal, when compared to Rossetti’s hand, seems to clearly point in that direction. It’s this or Rossetti had really large hands.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens, and Thomas Woolner. They formed a seven-member “Brotherhood” modeled in part on the Nazarene movement. The Brotherhood was only ever a loose association. Their principles were also shared by other artists of the time, including Ford Madox Brown, Arthur Hughes, and Marie Spartali Stillman. Later followers of the principles of the Brotherhood included Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris, and John William Waterhouse.

An important episode for our story is the 1857 commission received by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The goal was to decorate the vaulted ceiling, upper walls, and windows of the library of the Oxford Union. Rossetti quickly gathered a vast group of helpers. These included Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris, Roddam Spencer Stanhope, Arthur Hughes, John Hungerford Pollen, and Val Prinsep.

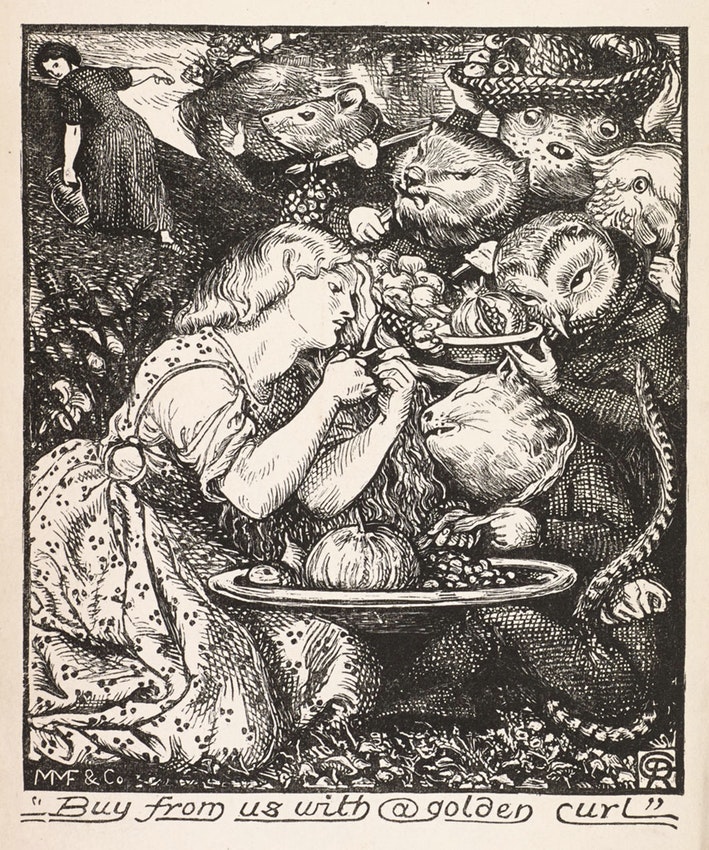

During that work, the artists entertained themselves by drawing numerous wombats in the whitewash. All obviously covered up later by the frescoes. These themselves didn’t last in a good condition. This is how Prinsep wrote about this commission: “Rossetti was the planet around which we revolved, we copied his way of speaking. All beautiful women were “stunners” with us. Wombats were the most beautiful of God’s creatures.”

We don’t know really where the Pre-Raphaelite’s love for the wombat originates. The only one of them to actually go to Australia was Thomas Woolner. He didn’t like it there too much, sending his friends long journal-letters.

In 1862, Rossetti had moved to Tudor House, at 16 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. As soon as he arrived, Rossetti began to fill the garden with exotic birds and animals. There were owls, including a barn owl called Jessie, two or more armadillos, rabbits, dormice, and a raccoon that hibernated in a chest of drawers. He also had peacocks, parakeets, kangaroos, and wallabies.

Charles Jamrach was a leading dealer in wildlife, birds, and shells in 19th-century London. He was also Rossetti’s supplier. He owned an exotic pet store on the Ratcliffe Highway in east London. At the time it was the largest such shop in the world. After a Bengal tiger escaped from its box at the Emporium in 1857, and picked up and carried off a passing eight- or nine-year-old boy, Jamrach “came running up and, thrusting his bare hands into the tiger’s throat, forced the beast to let his captive go”. The boy, who had approached and tried to pet the animal having never seen such a big cat before, sued Jamrach and was awarded £300 in damages. George Wombwell later bought the tiger. It became a popular attraction at his menagerie.

In November 1867, Rossetti was negotiating with Jamrach. His object was to purchase a young African elephant, but he balked at the price of £400. Rossetti’s income for 1865 was £2000.

In September of 1869, he bought the first of two pet wombats. This was the culmination of well over 12 years of enthusiasm for the exotic marsupial.

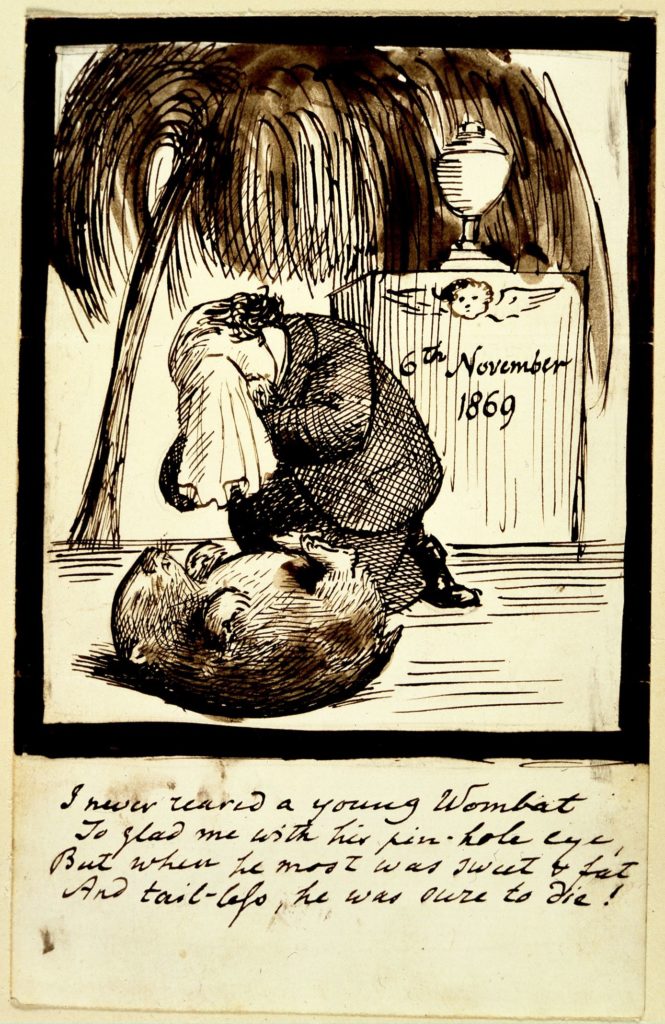

I never reared a young Wombat

To glad me with his pin-hole eye,

But when he most was sweet & fat

And tail-less; he was sure to die!

This wombat arrived in September 1869, when Rossetti was away in Scotland. He had a breakdown, largely caused by failing eyesight, insomnia, drugs, and above all his growing infatuation with Jane Morris, the wife of his old friend and protege from the Oxford Union days.

There is a remarkable drawing of Jane Morris and the wombat in the British Museum. Each of them wears a halo and Jane has the wombat on a leash. It seems that Rossetti used the wombat as a cruelly comical emblem for Jane’s long-suffering, cuckolded husband. In his university days Morris became known to his friends as ‘Topsy’; the name Rossetti chose for his Wombat was ‘Top’.

Rossetti returned to London on September 20th, and the next day wrote to William Michael his most famous and suggestive remark about the new addition to his menagerie: ‘The wombat is a joy, a triumph, a delight, a madness’. Unfortunately, the poor wombat was also an invalid. It didn’t live long, on November 6th, the wombat died. Rossetti had him stuffed and afterward displayed him in his front hall.

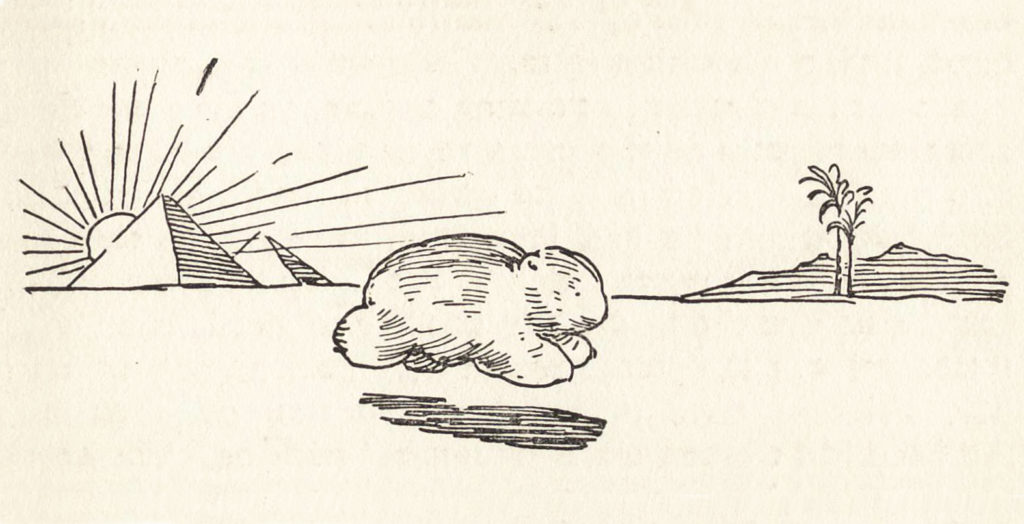

The cute wombat running along the pyramids is one of many drawings of this animal by Edward Burne-Jones. His wife, Georgiana Burne-Jones., used it in Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, mentioning among other things the Oxford Union times with Rossetti.

Georgiana Burne-Jones was also an artist, though not many of her works survived. She also wrote Edward’s biography at his request. He wanted to ensure that no one unsympathetic would take on this task. In 1905, Georgiana arranged the publication of The Flower Book, a limited-edition facsimile of an album of watercolor flower paintings by Edward Burne-Jones.

Georgiana was not only a curator of her husband’s memory however. She was also very active in politics. In 1895, Lady Burne-Jones took her first steps into elected office, winning a seat on the parish council of her beloved Rottingdean. This to the apparent delight of both her husband and her old friend William Morris. She supported interests of the working class and women’s issues, taking positions in her electioneering materials that were radical for the wife of a baronet and simply baffling to the villagers of Rottingdean. Her day-to-day work in the parish focused on street lighting, fire brigades, and the provision of a village nurse for the community.

While she worked on the Memorials, Georgiana remained active on the Rottingdean parish council. Her politics became if anything more radical as she grew older. At the outbreak of the Boer War, Georgiana opposed Britain’s action in South Africa. When news of the relief of the siege of Mafeking arrived, Georgiana hung a banner at North End House. It read “We have killed and also take possession,” paraphrasing a verse from the Bible. Her nephew, Rudyard Kipling, rushed to her house to ensure she would not fall victim to an outraged mob of villagers.

Her portrait by Edward and her strong will could inspire the character of Catelyn Stark from the Game of Thrones.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!