10 UNESCO World Heritage Sites to Visit in France During the Olympics

Visitors to the Olympics will not only be able to enjoy the sports while supporting their favorite countries and athletes. France offers an unusual...

Ledys Chemin 29 July 2024

Just about everyone has heard of Edgar Degas, the famous painter of dancers. However, the works Degas created in modern America’s favorite party capital, New Orleans, are commonly overlooked. Read about his time in the US.

In his five months abroad, Edgar Degas captured endearing portraits of his Creole family as well as scenes of a bustling, yet recovering city. The Civil War had recently ended, leaving behind a ravaged, war-torn New Orleans facing Reconstruction. This provided Degas with plenty of inspiration for several paintings. It also profoundly influenced the direction he would take with his art. One could argue his paintings from this period proved him to be more than “the painter of dancers”.

While other Impressionists had ties to the New World, Edgar Degas is the only one to ever set foot in America and create work there. And his ties ran deep. The word, “Creole” has meant many different things throughout the centuries. For the Musson family, it meant that Celestine, Degas mother, was descended from some of the original French and Spanish settlers of New Orleans. The book, Degas and New Orleans, explores the intimate and often unsuspected connections between the black and white branches of Degas maternal family.

Celestine’s father, Germain Musson, further established his family’s roots and influence after fleeing Haiti in 1804 and making a fortune in Louisiana cotton and Mexican silver. After the sale of a young slave girl boosted her already respectable dowry, Celestine married a banker, Auguste De Gas, who favored the pseudo aristocratic spelling of his surname. The pair moved to France, where they had three sons, Hilaire Germain Edgar, Achille, and René Degas. To simultaneously celebrate her eldest son Edgar’s birth and link him to the “mother country,” his father arranged for a small Creole cottage on Rampart Street to be purchased in the infant’s name.

As a child growing up in Paris, Edgar became fascinated with Louisiana. His mother frequently told stories of her home and the family was often visited by Edgar’s grandfather, Germain Musson, who brought news of family and friends in America. The young artist dreamed of one day being able to walk on the land of his ancestors.

It was not until 1872, at the age of 38, that Edgar finally got his chance. His brother, René, took leave from working in the family’s New Orleans cotton office and spent the summer of that year in Paris with Edgar. René invited Edgar to travel back with him. Given the hardships he faced in his military service during the Franco-Prussian war and an increasingly stale professional life, Edgar needed little convincing. So, the pair set sail for Louisiana in October of 1872.

Upon being warmly welcomed by his family and exploring the city, Edgar Degas became enchanted by its beauty. Shortly after his arrival, he wrote of the scenery to a Parisian friend, James Tissot:

Nothing pleases me more than the black women of all shades, holding little white babies that are oh so white in their arms, in white houses with fluted columns surrounded by orange-trees and magnolia gardens […]. The ladies in muslin in front of their little houses and the steamboats with two smokestacks, as high as the twin chimneys of factories and the fruit merchants with shops full to overflowing. And the lovely pure-blooded ladies and the beautifully planted quadroons.

Edgar Degas, letters.

His uncle, Michel, rented one of the beautiful white houses on Esplanade Avenue that Degas walked frequently and likely inspired the previously mentioned letter. The artist was given his uncle’s room and a workshop for painting for the duration of his stay. He developed a routine: walking to the family cotton office to peruse the newspaper and write to his friends and colleagues in France. Leisurely evenings were spent conversing with his family. René wrote of Edgar’s curiosity surrounding his family’s lives. He was particularly enchanted by their southern accents and his attempts to imitate them. As a native Southerner, I am sure that was entertaining!

During his stay, Edgar created captivating portraits of his family. The artist realized something we have all come to realize in these times of self-quarantine: working and living with family can be quite irritating. Imagine his frustration as he attempted to pose children and capture a family portrait with a hungry baby. Edgar expressed this frustration, writing,

The subjects are loving but rather brazen, and they are less inclined to take you seriously because you happen to be their nephew or cousin.

Edgar Degas, letter, France-Amerique.

However, that did not stop Edgar Degas from meeting his family’s requests of creating tender, captivating portraits of them. His cousins, Estelle, Mathilde, and Désirée Musson, were frequent sitters for him. Estelle is a cousin he painted many times. Oddly enough, Estelle was also Edgar’s sister-in-law through her marriage to René. The portrait below is considered one of his most successful portraits.

Here, the pregnancy of her fourth child is hidden in the billowing skirts of her loose dress, a testimony to the sitter’s formality and modesty. Motherhood was a somber subject for Degas. At age 13, his mother, Celestine, passed away, leaving a profound impact on Edgar as well as his art. In Degas’ paintings portraying motherhood, such as Madame René de Gas, motherhood is associated with mourning, much like Degas associated it in his own mind. As if reflecting a solitude associated with mourning or the sitter’s blindness, Estelle sits alone, gazing away from the viewer. The silvery light and combination of muted pink tones work together to reflect Estelle’s calmness.

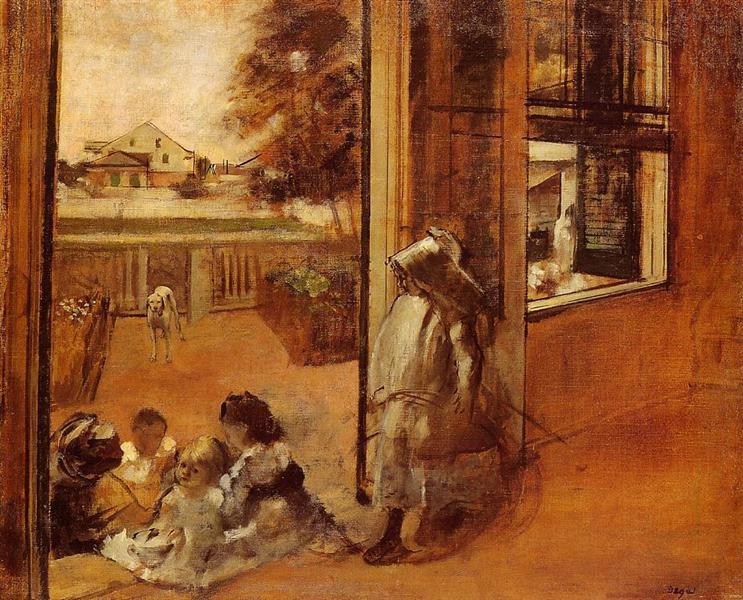

Despite the seemingly peaceful energy in most of his paintings from this period, all was not well in the Degas family. Around August of 1873, René left Estelle for a neighbor, America Durrive Olivier. The two ran away to France where they began a new life (and family) together. In consequence, Edgar and René did not speak for years and the surviving children reclaimed Estelle’s maiden name, Musson. Edgar’s painting, Children on a Doorstep, foreshadows, or perhaps, hints at this rift. It depicts several children, presumably Estelle’s, distractedly playing. However, none of their faces are as clearly portrayed as that of the family dog. In addition, the house visible through the door is none other than the Oliviers’.

Perhaps his most famous work from his southern stint is A Cotton Office in New Orleans. Edgar Degas extended his stay by three months to allow time to finish this piece as he had planned to sell it to a museum.

Here we see a pivotal moment in the family business, facing potential financial ruin. A worker inspects the quality of the cotton before him. Meanwhile, René nonchalantly scans the newspaper, perhaps reading an article about their own bankruptcy. The third brother, Achille, seems uninterested as he leans against the window at the left. Edgar’s uncle, Michel, sits in the foreground wearing a top hat, toying with a ball of cotton. All around them, their employees go about their business as if they can somehow rescue themselves from imminent financial calamity. Unfortunately, their efforts were fruitless, and the business went bankrupt before the painting was finished.

If Degas had painted the office and its employees as seen every day, there would have been African-American porters carrying cotton samples to and from storage. Even in his paintings set in the family home, one might expect to see an African American servant. However, the artist has decided to exclude these individuals. In the 1870 Louisiana census, there were 364,210 free African Americans and 362,065 whites in the state. This means Degas encountered and saw many African Americans every day.

Christopher Benfey, the author of Degas and New Orleans, believes this relates psychologically or socially to the Musson family’s tricky, mixed lineage and his relatives’ involvement in the Crescent City White League. This fundamentally racist group was determined to wrench political power from the more diverse, but no less corrupt post-Civil War carpetbaggers.

At the time of Degas’ visit, the mix of family, race, and politics was of a mild concern among them. This is understandable given the city’s post-war, Reconstruction frenzy. During this time Creoles, like the Mussons and Degas, found themselves fighting to keep their names and French heritage atop New Orleans society as the city grew towards becoming an American metropolis. Mr. Benfey states,

In summary, the exotic for Degas hit a bit too close to home.

Before returning to Paris, Edgar Degas worked on about two dozen pastels, drawings, and paintings. The pieces he created during this time show a side of Degas that is often overlooked and is rarely scrutinized. Each of the paintings from this period are not simply brooding portraits of dull family members. As a collection, they are quite somber and were created with empathy, as well as intellect. When we take a closer look at Degas’ family history and the works he created in his ancestral home, we gain an insight into the complexities of New Orleans’ tumultuous and vexed history.

While Degas Southern American experience was brief, it led him to make a decisive step in his artistic development. Upon returning to France he decided to stop painting the popular historical subjects inspired by Neoclassicism. Instead, he followed the pattern he developed in New Orleans, creating scenes he witnessed in everyday life. In his post-New Orleans career, he frequently drew and painted ballerinas, musicians, and cafe patrons as his subject matter. Thus earning him the debatable title “painter of dancers”. Despite the artist’s unwillingness to anchor himself to a group of painters and accept his title as “painter of dancers,” his works from New Orleans as well as his infamous ballerinas have earned him a place among the Impressionist masters.

P.S. If you find yourself escaping to New Orleans, be sure to take a tour of the Degas House! It still functions as a bed and breakfast, event venue, and museum run by Degas’ descendants!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!