5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

Let’s explore the history of still life through a selection of 10 paintings corresponding to two key moments: the 17th century in the Netherlands, and the 19th century in France. Dutch and Flemish artists painted still lifes with great skill, sometimes with the goal of communicating moral messages. In the late 19th century, everyday use objects became subjects of formal exploration in terms of color, style, and composition for impressionist and post-impressionist French painters.

A still life is a work of art where the predominant subject matter is that of inanimate objects, either natural or man-made. The pictorial representation of objects exists since Antiquity, but it was not until the Renaissance that still life emerged as an independent genre. Still Life with Partridge and Gauntlets (1504) by Jacopo de’ Barbari is generally considered the first of its kind. The term “still life” derives from the Dutch word stilleven, which literally means motionless or silent life. This terminological detail reminds us that this genre had its heyday during the Dutch Golden Age.

Frans Snyders (1579-1657) painted classical still lifes of fruits and flowers but is best known as a painter of animals due to his great ability to represent fur and feathers. He painted hunting and animal fighting scenes, as well as still lifes in which he combined fruits, vegetables, and game, or included live animals in the composition. The Fruit Girl is a good example of an opulent still life of the Flemish Baroque. Beyond its artistic qualities, this painting evokes prosperity and wealth.

Snyders was a collaborator of Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob Jordaens, and was the principal painter to the archduke of Austria, Albert VII. His work was also highly appreciated in Spain, where he took part in the decoration of the Torre de la Parada, a former hunting lodge situated near the Royal Palace of El Pardo. Today, 28 of his works may be seen at the Museo del Prado.

Willem Claesz Heda (1594-1680) and Pieter Claesz (1597-1661) were Dutch Golden Age painters devoted to still life. As we can see in the pictures below, both painted with almost monochromatic palettes of sober color, paid special attention to texture, and were masters of capturing the reflection of light on various objects. The objects on which the effects of light are most evident are the glass objects: a roemer (or rummer) – a large glass which dominates the composition in both paintings– and a tazza– the decorated silver goblet which appears on the right side of the painting by Pieter Claesz.

Still Life with Ham by Floris van Schooten (1585/1588-1656) evokes a mixture of conventionality and spontaneity. The food is painted with great technical virtuosity and the composition follows the rules of the time. 17th-century Dutch painters often depicted cheeses piled in a pyramid, with large and yellowish ones on the bottom, and small, dark, and more mature ones on top. However, at the same time, the table is set for an informal and possibly improvised meal, and the food is in the process of being eaten (see, for example, the recent marks of a knife in the cheese found at the bottom of the pyramid).

In the context of 17th-century Dutch painting, this kind of still life, depicting light meals and following a strict set of compositional rules, is known as ontbijtjes which literally means small breakfasts. They may be understood in a more general sense as the depiction of snacks or light meals to be taken at any time of day. Willem Claesz, Heda, and Pieter Claesz, whose works we have seen above, were also specialists in ontbijtjes.

A Table of Desserts is probably the earliest still life by Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606-1684). It belongs to his Antwerp period, where he moved in 1635 after having previously lived in Utrecht and Leyden. This painting more closely resembles the luxurious work by Snyders than the austere ontbijtjes that we have just seen. Besides a wide variety of food and sumptuous utensils, de Heem depicts two musical instruments: a lute and a recorder. In formal terms, this work impresses because of the precise depiction of textures, the skillfully painted light effects, and the almost theatrical composition. As Adeline Collange wrote in her description of the painting for the Louvre Museum, it is “a brilliant synthesis of Dutch precision and Flemish Baroque.” Also, in terms of meaning, it transmits a message about the ephemeral nature of the pleasures of the senses. This reflects the symbolism that de Heem learned in Leyden and makes the painting resemble a vanitas, a kind of still life aimed at transmitting moral messages on the futility of pleasure.

The fauvist artist Henri Matisse (1869-1954) painted his own interpretation of A Table of Desserts. The work is on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This takes us to the following section in which we explore five still lifes made by impressionist and post-impressionist French painters.

During the decade between 1860 and 1870, Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904) painted several still lifes. He was contemporary to painters who later formed the impressionist group, but his style remained more academic. As we see in Flowers and Fruit on a Table, his compositions often included flowers. Many of his still lifes were appreciated and sold in England, where he also found a patron in the wealthy collector Edwin Edwards.

The Brioche by Édouard Manet (1832-1883) was probably inspired by Jean Siméon Chardin’s painting of the same title that the Louvre had recently acquired. However, Manet’s brushwork and use of light make the painting unique, emphasizing the soft and creamy texture of the famous French brioche. This painting displays Manet’s skill in a genre that he considered “the touchstone of the painter.” Still lifes constitute approximately a fifth of the painter’s oeuvre and were key to his artistic practice. He reportedly said that painters could express anything they wanted with fruits, flowers, and even clouds.

The next painting is by Claude Monet (1840-1926), the initiator of Impressionism. Still Life with Melon depicts the fruits of summer and dishes that resemble Chinese porcelain. Its round forms and carefully arranged composition, which slightly reminds of Fantin-Latour’s Flowers and Fruit on a Table, are very pleasant to the senses. Through colors and light, this painting achieves the impressionist goal of transmitting life-like sensations. It feels as if we could taste the sweetness of the fruits.

Monet’s artistic style was present in diverse spheres of his life. Walking through his house and gardens in Giverny is like immersing oneself in his paintings. He also took an interest in the culinary arts, learning recipes and entertaining guests for a meal were part of the art of living for him. Among his guests were the painters Auguste Renoir and Paul Cézanne, as well as the former Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau. Les Carnets de Cuisine de Monet is a very informative and well-written book based on his recipes.

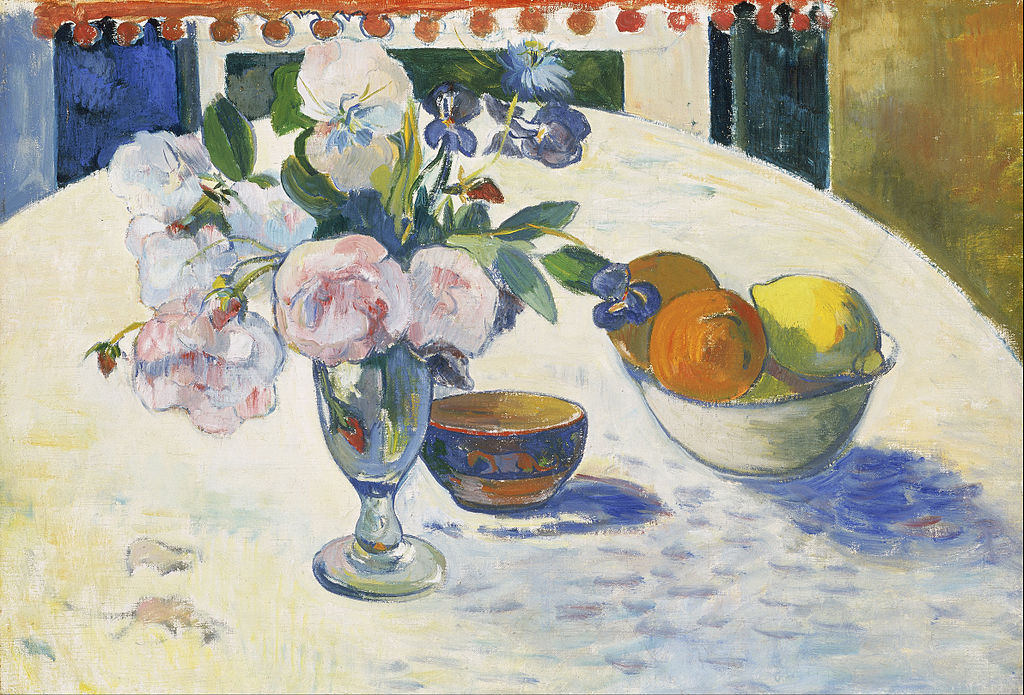

As we approach the 20th century, we observe a transition towards less figurative painting. Less realistic shapes and compositions characterize works dating from the last decade of the 19th century. Straw-Trimmed Vase, Sugar Bowl and Apples by Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) and Flowers and a Bowl of Fruit on a Table by Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) are telling examples.

Fruits are drawn as simplified round shapes and the improbable inclination of the tables shows a turn away from a realistic perspective. In Cezanne’s painting, for instance, we get the impression that the objects are about to fall. Such visual effects were common across the diverse post-impressionist styles.

Later, already in the 20th century, Pablo Picasso reinterpreted still lifes in a cubist manner. His Large Still Life (1918), which shows a table inclined towards the viewer and objects based on geometrical shapes, bears resemblance to Cézanne’s work.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!