Madness in Art: A Powerful Connection

Madness and art have long shared a profound and powerful connection, where the boundaries between genius and instability often blur. Many acclaimed...

Maya M. Tola 28 October 2024

Recently, people worldwide have experienced a sense of being “in the midst of an apocalypse.” Why do individuals instinctively link this term to feelings of desperation and hopelessness during challenging times? This association is largely influenced by the ubiquitous exposure to dramatic artistic representations of the renowned, enigmatic, and extravagant Book of Revelation and The Apocalypse.

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament of the Bible, probably written by Saint John. The other name “apocalypse” comes from the first word of the Greek text: apokalypsis, meaning exactly “unveiling” or “revelation.”

The book is full of symbolic and obscure images which, therefore, can be interpreted in various ways. Some scholars thought that the events described were a representation of the whole history of mankind, or just of the first centuries of Christianity. Others were sure that the book was a series of prophecies about the nearing end of the world and the opening of the kingdom of God. Meanwhile, in another view, the Revelation is just an allegory of the spiritual path and the struggle between good and evil.

However, the (most) correct interpretation does not matter. The important point for artists (and often for their patrons) was the power of apocalyptic scenes. This made them an ideal subject for majestic, shocking, and unforgettable oeuvres. In this way, religious people could use them as a warning for the end of either every person individually or of mankind in its entirety, thus imploring people not to sin anymore. Additionally, artists could be remembered forever thanks to their incredibly powerful works.

Although a lot of events happen in the book, three are especially favored moments by artists.

In Chapter Six, four mysterious creatures ride four unnatural horses: a white one, a red one, a black one, and a pale one. Only the identity of the fourth rider is surely known: it is Death.

And I looked, and behold, a pale horse, and the one sitting on it, the name of him was Death, and Hades was following with him.

Revelation 6:8.

The other three horsemen do not have explicit names, but surely they come to help Death destroy everything. They are probably Famine, War, and Plague/Pestilence. In other interpretations, they are Conquest, War, and Pestilence (or Famine).

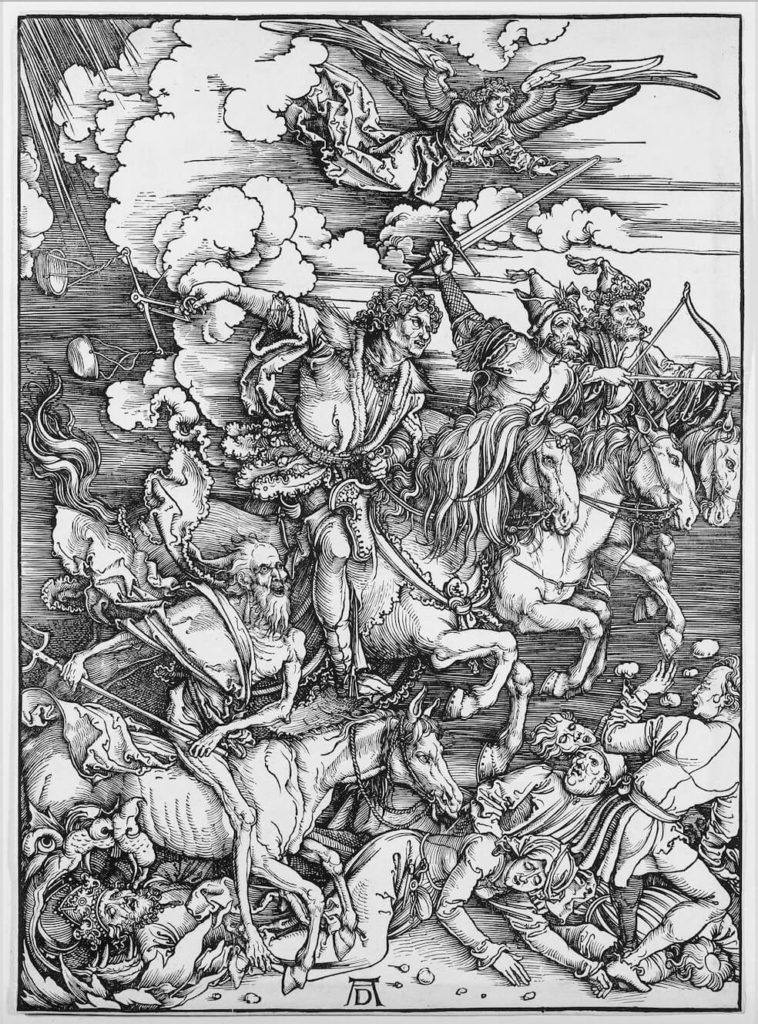

Albrecht Dürer did a series of 15 woodcuts about the apocalypse. The most famous of them is The Four Horsemen. He transformed a previously static and boring image into a representation full of motion and danger. Thanks to his mastery, the observer can almost hear the horses’ hooves clopping!

Dürer’s genius was even able to translate the distinctive colors of the horses into a black-and-white medium, making the characters recognizable through weapons and order of apparition. In fact, the horsemen seem to appear from background to foreground, slightly overlapping, in the same order as they appear in the book. The parallel lines crossing the image give both a direction and a middle tone. The lines also create the illusion that the horsemen are actually riding across the composition from left to right. Meanwhile, the tone allows the figures to powerfully emerge through contrast. Finally, the lines are used to recreate the Mouth of Hell, just in a slightly diagonal direction (upper left).

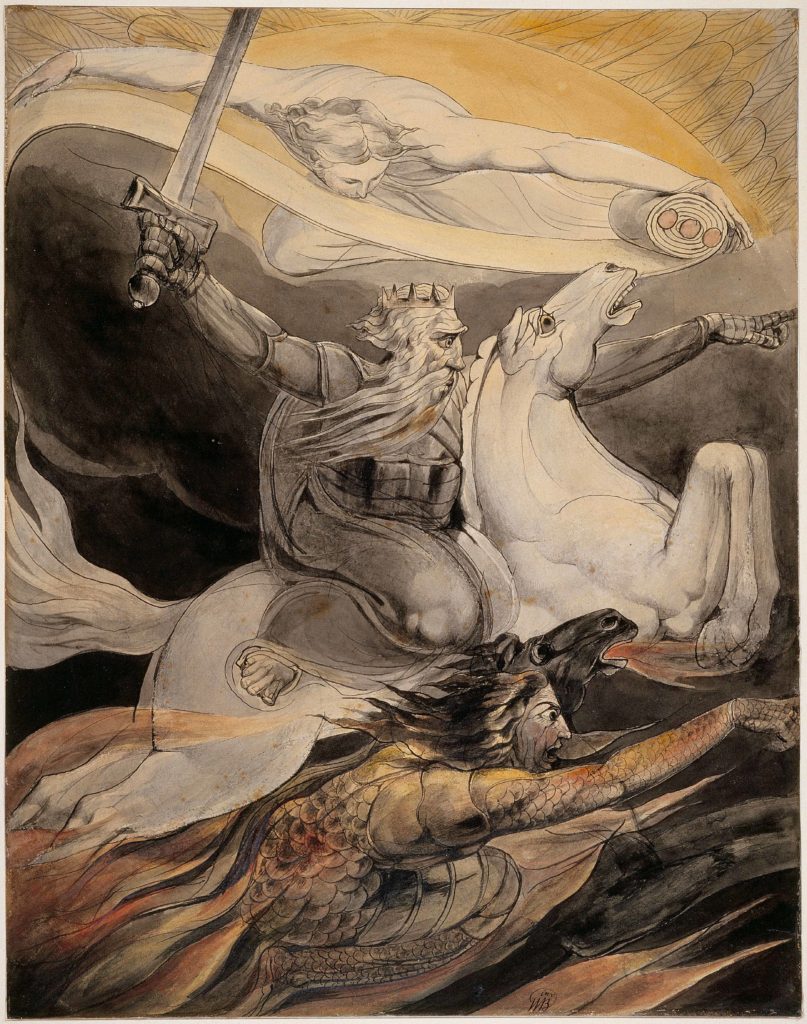

While William Blake preferred to represent only Death on a Pale Horse, the rider on the black horse (probably Famine or Plague) actually appears here too.

This watercolor is extremely energetic, more definitely directed toward the upper right. Like in Dürer’s woodcut, a figure in the upper part of the work seems to be an angelic presence. This is suggested by feathers and is probably an image of divine protection. In this work, colors help to give a precise identity to the figures without adding further detail, especially creating the atmosphere of a nightmare.

Chapter Twelve opens with the appearance of a very particular woman:

A great and wondrous sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head. She was pregnant and cried out in pain as she was about to give birth.

Revelation 12:1, 2.

The woman gives birth to a male child who is threatened by a dragon, identified as the Evil. However, God takes away the child and immediately afterward, war breaks out in Heaven.

The impact of this majestic woman, generally identified as the Virgin Mary but in other opinions, an allegory of the Church itself fascinated many artists. These included the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens. He created an oil sketch of the subject, meant to serve as the modello for a vast altarpiece.

A landscape is perceivable mainly on the bottom right, while a tumultuous heavenly battle wraps around the central figure of the woman. She shows some traditional iconic details of the Virgin Mary: she wears a white and blue dress and is crushing the head of a serpent. The whole masterpiece is a literal representation of chapter twelve – there is even the crown of stars. Above, God the Father instructs an angel to place a pair of wings on the woman’s shoulders. At the same time, the child looks and reaches toward Him. Rubens had the ingenious idea of painting God in a faint manner in order to suggest His spirituality.

The most powerful scene of from the Apocalypse is definitely the Last Judgment, the principal theme of Chapter Twenty. Part of this fame is certainly due to the incredible work of Michelangelo in Rome. Many other artists have however depicted this subject in their own personal way.

Two hundred years before the Sistine Chapel, painter Buonamico Buffalmacco realized two related frescoes representing the Last Judgment and Hell in the Cemetery of Pisa. In Gothic art, artists should follow a canon for the representations. For example, they should include the New Jerusalem at the top of the work and Christ dividing the scene into good people and the damned. Although not breaking these rules, Buffalmacco introduced some very interesting and original elements.

He had a larger space than usual, so he took advantage of this; painting the Hell fresco next to the Last Judgment instead of below. Moreover, both Christ and the Virgin conduct the Judgment. The temper of Christ is also interesting: severe, condemning, with a raised arm. Did Michelangelo study these frescoes, perhaps?

In the part of Hell, a huge, green Satan shocks the viewer. All around him, the damned people occupy different zones like in Dante’s Divide Comedy.

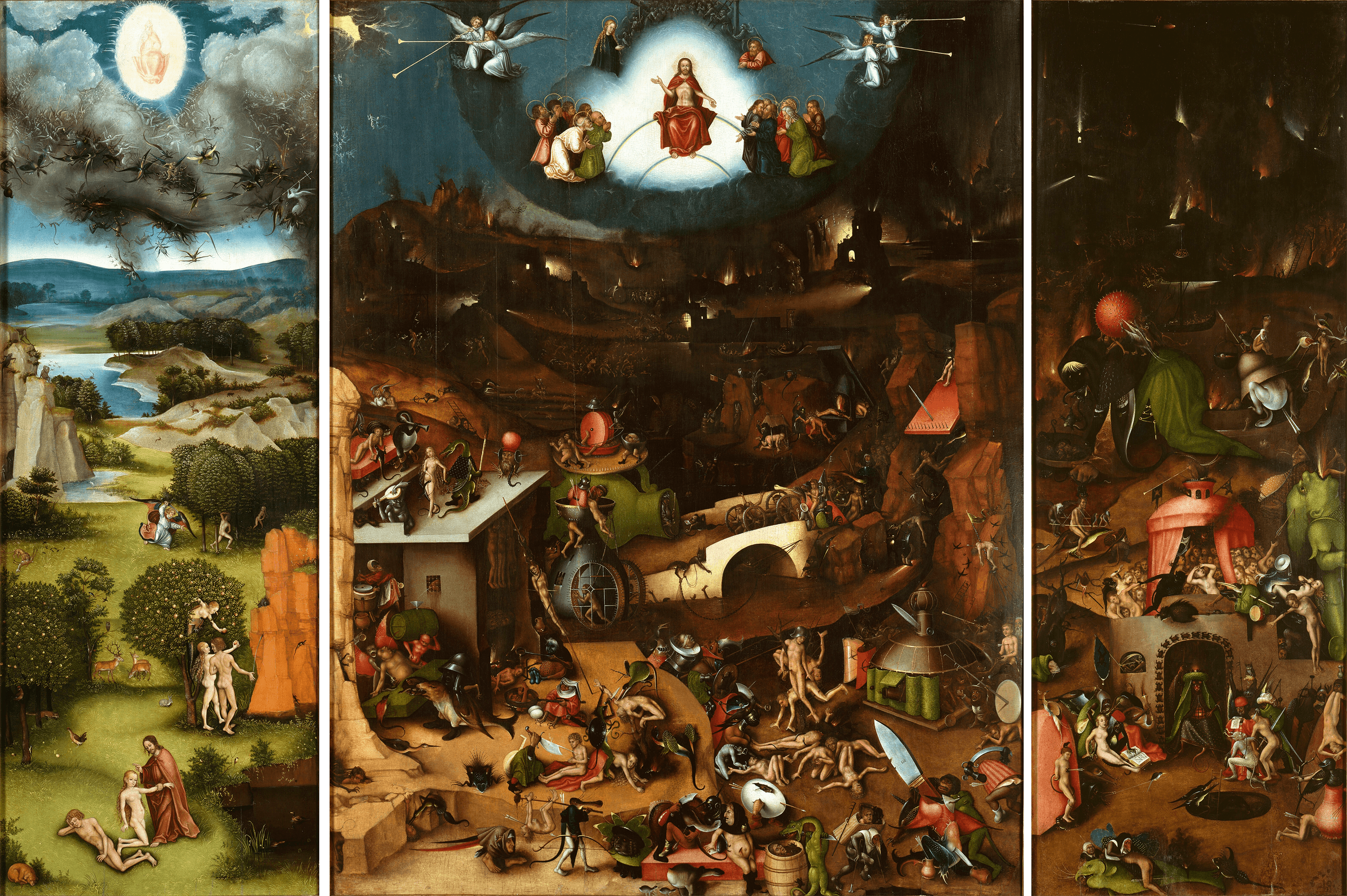

The same subject but different details for Hieronymus Bosch. Bosch’s Last Judgment is a triptych and is filled with his typical dream-like elements. The central panel represents the actual Last Judgment, where Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and the apostles look down on a chaotic earth. As usual, Bosch’s tiny figures often do not wear clothes, face strange creatures, and sometimes do battle. The dominant color is vermilion red. On earth, it is probably a symbol of the dangers of human passions, while on Christ’s robe it may be the allegory of His status as God. The panel on the left represents the expulsion from the Garden of Eden. On the right, instead, like in Buffalmacco’s frescoes, Bosch painted a representation of Hell in which green demonic creatures surround the damned.

In the 20th century, some painters rediscovered the apocalyptic theme. However, they did not represent specific scenes, but rather the feelings of uncertainty and fear which permeates a possible end of the world.

Being the father of abstract modern art, Wassily Kandinsky made his own Last Judgment without figures. He “only” used colors and forms that could effectively represent the strong emotions evoked by the apocalypse. The center of the painting has a small, irregular, black shape. Surrounding it is a vortex of colored lines and dots. Open-ended and closed shapes overlap colors and dots. This circular motion may recall the tumultuous movement downwards into Hell.

More recently, an American painter Nabil Kanso depicted the apocalypse in a series of over 150 paintings and works on paper done from 1982 to 1984. In these works, some figures return but no specific scenes of the apocalypse are represented. A real sense of terror is immediately provoked in the observer by the dark and violent colors. The sketched expressions of the human-like creatures even increase this feeling. This sort of generalization of the apocalypse also makes it more universally comprehensible.

What if the meaning of “apocalypse” were even further extended, including real disasters like wars? See here for a perfect example!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!