Between Word and Image: The Creative Mind of David Jones

David Jones (1895–1974) was an artist, poet, writer and craftsman; a name synonymous with the Modernist era but one that still remains lesser known...

Guest Profile 21 October 2024

14 October 2024 min Read

Max Ernst (1891–1976) was a prolific German avant-garde artist. He was a pioneer in the early 20th-century movements of Dada and Surrealism and developed a number of inventive artistic techniques. Ernst had the ability to make the unbelievable believable through his art. For this reason, he remains to this day one of the most complex Surrealist artists. Max Ernst also developed a fascination with birds which manifests itself throughout his work.

This odd fixation came after a rather dark incident he experienced as a child. The way he tells it, his favorite pet bird died at the moment his younger sister was born. He subsequently started to view birds as omens of death, the opposite of what they traditionally symbolize. Eventually, he permanently conflated the two. Thus Loplop, the Bird Superior and Ernst’s Freudian alter ego was born. This other avian self consistently and persistently appears throughout his work.

Usually, birds in art symbolize freedom, hope, and peace. However, Ernst’s interpretation of birds seems inextricably linked to the supernatural. The feathered creatures he depicts in his art emit menace instead of optimism and recall darkness instead of light. Similarly, Loplop is an almost mythological, ambiguous creature acting as a guide to Max Ernst’s subconscious. He is there to guide the viewer through the journey they have embarked on by entering Ernst’s world.

The bird first appeared in the artist’s 1929 collage novel La Femme 100 Têtes, where Loplop serves as a narrator. From then on, this bird and all it came to symbolize became a primary preoccupation for him. Ernst felt the need to include Loplop, in his many manifestations, in almost every piece he produced during the following decades.

Surrealists are famed for developing their imagery out of the realm of (usually their own) dreams. This is what renders their artwork incomprehensible to anyone else but them. Ernst doesn’t stray far from that path. At first glance, his works look convoluted, inexplicable, and even “nauseous” as a critic Bosley Crowther called them back in the day. The titles of his paintings are equally mystical, with the intention of further puzzling the viewer. For this reason, it might be helpful to give some background information, further explanation, and visual analysis of some of Max Ernst’s most incomprehensible paintings that center around mystical birds.

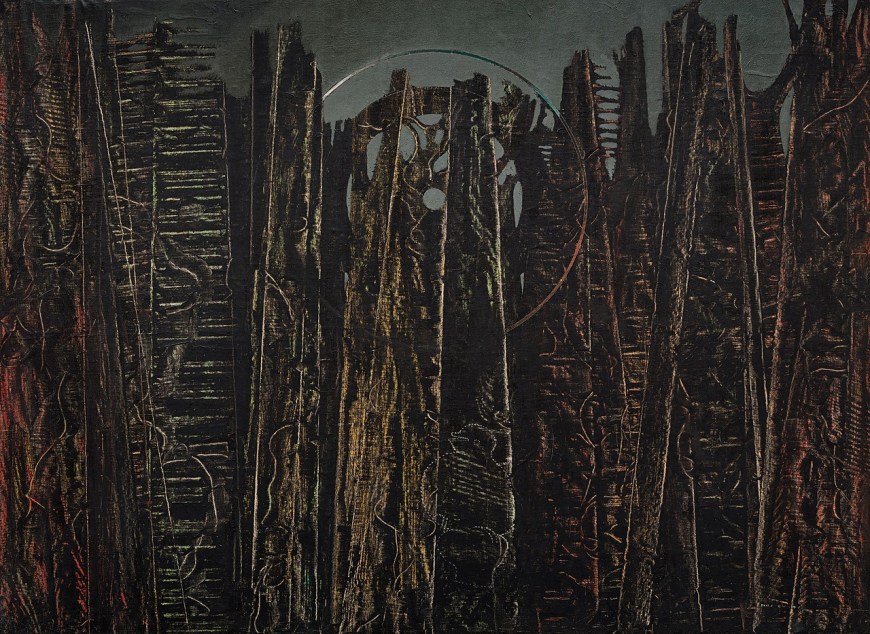

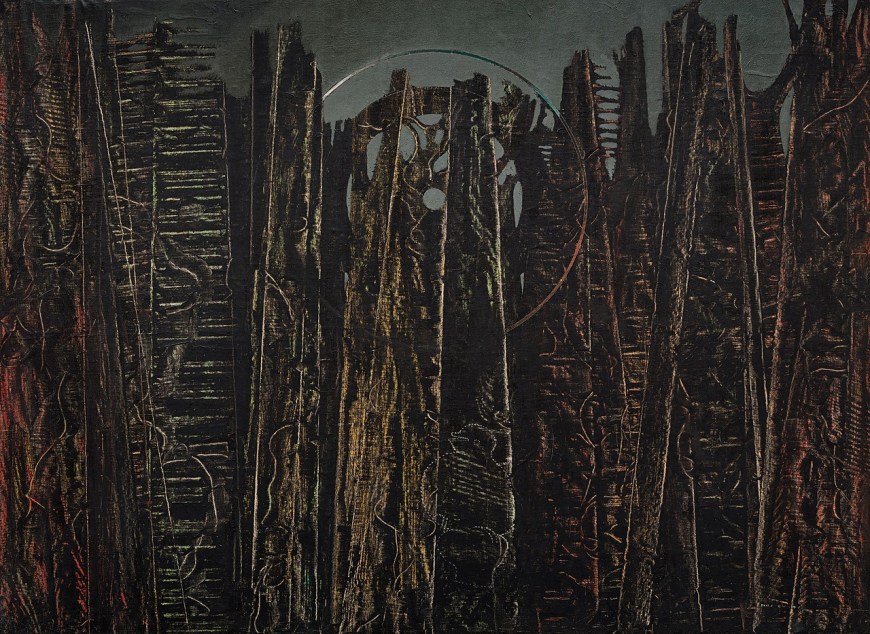

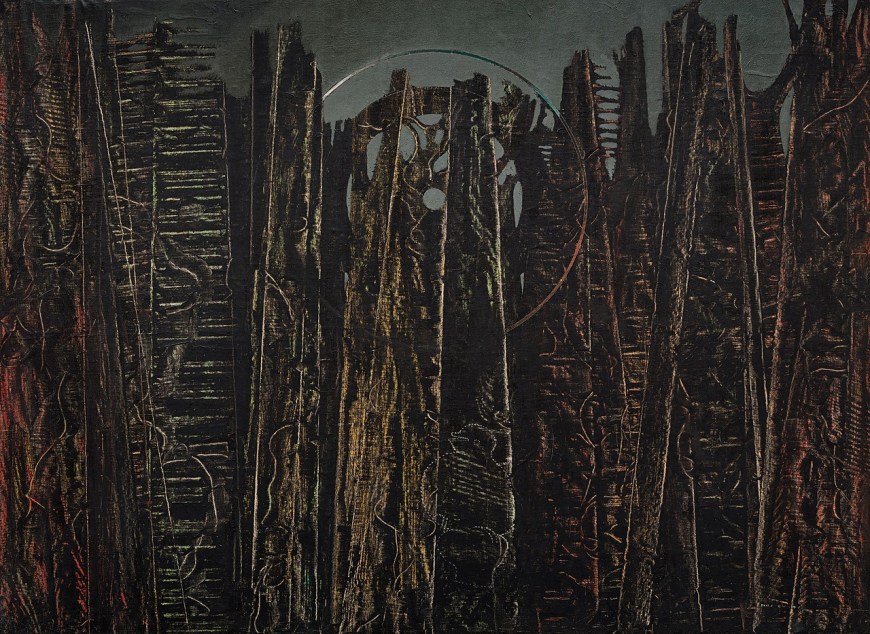

Max Ernst grew up in the town of Brühl, Germany. He was endlessly fascinated by the woods near his house. Forests appear often in Ernst’s works. He has said that wooded scenery reminds him of the “enchantment and terror” of the forest by his childhood home.

Forests are a potent symbol in the German tradition, which the Surrealists “adopted” as a metaphor for imagination. Art historian Charlotte Stokes writes that, by employing Freud’s methods of exploring the subconscious:

Max Ernst sensitized himself to his dreams, cultivated automatic responses and free associations, and contemplated memories of his childhood, never ignoring the symbols and traditions from the German culture into which he was born. By analyzing the symbolism of his dreams and other unguarded thoughts, he discovered that for him birds had a personal as well as a general significance.

– Charlotte Stokes.

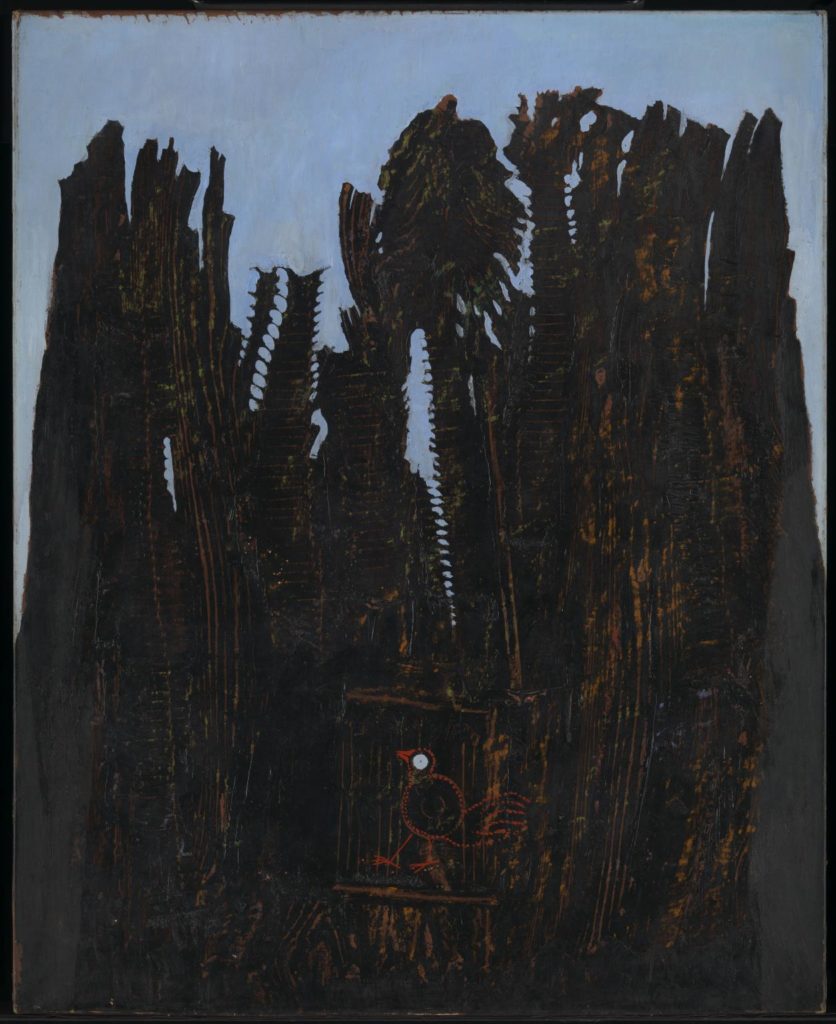

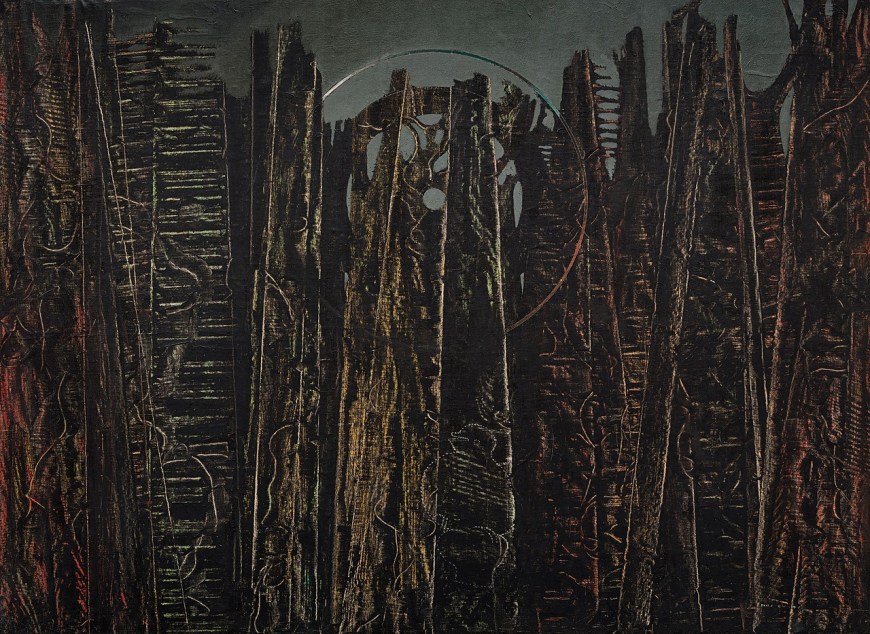

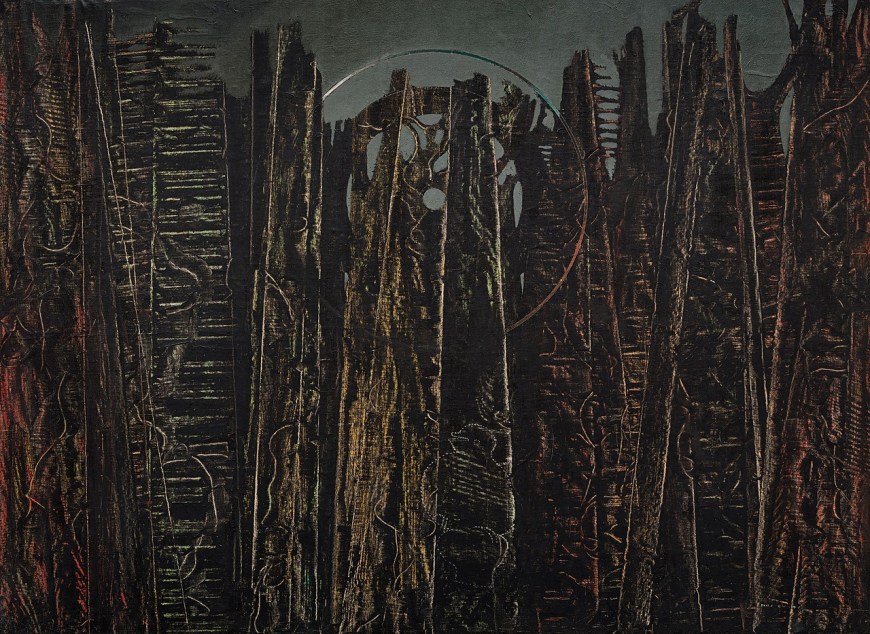

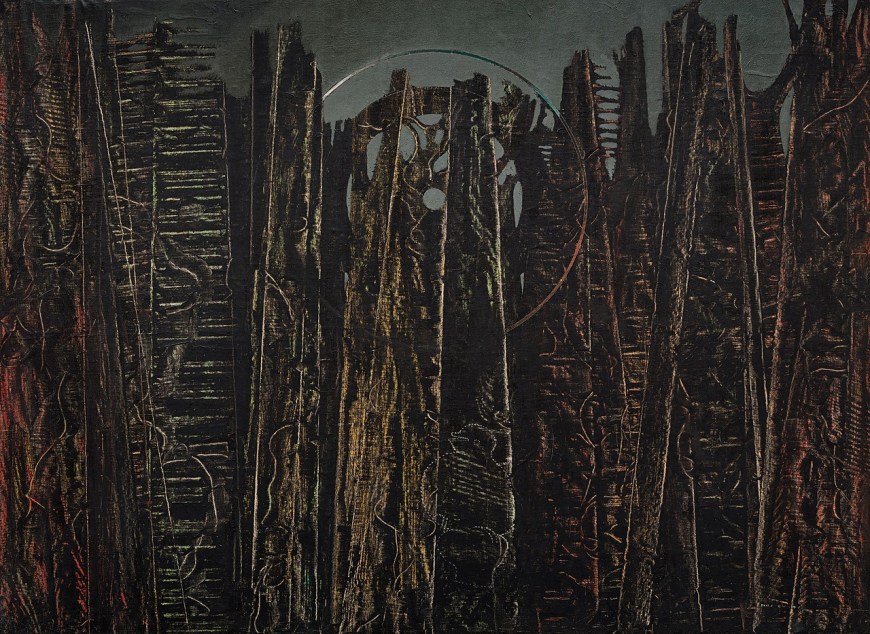

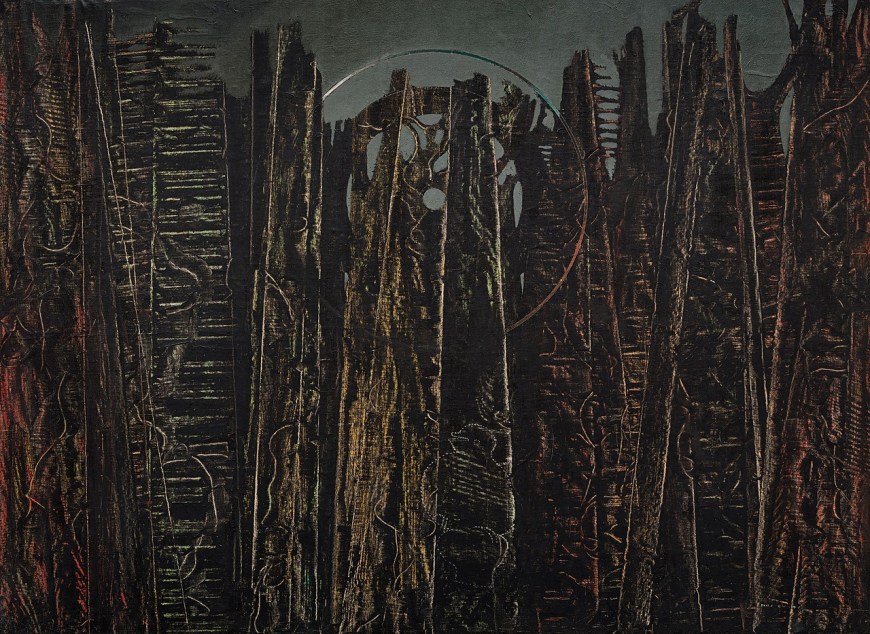

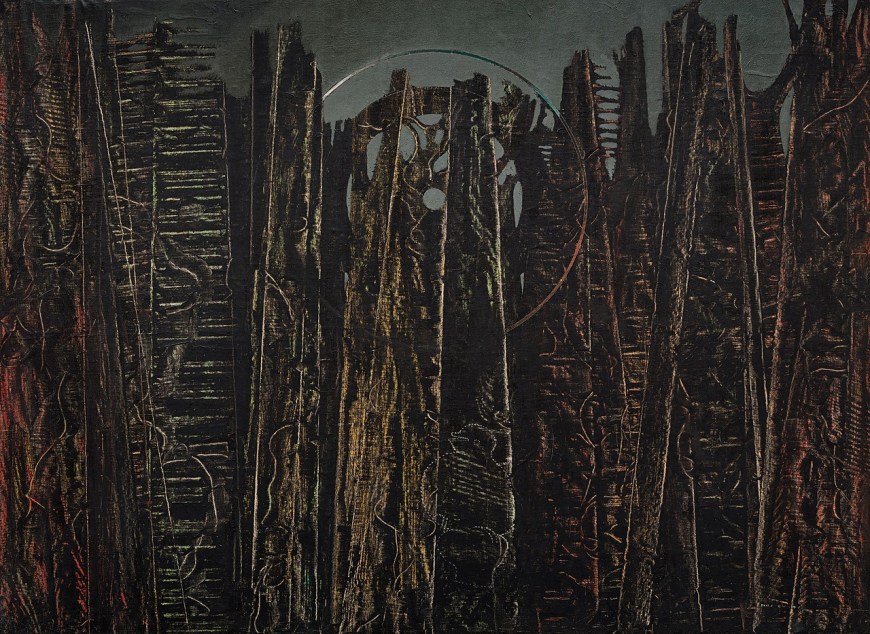

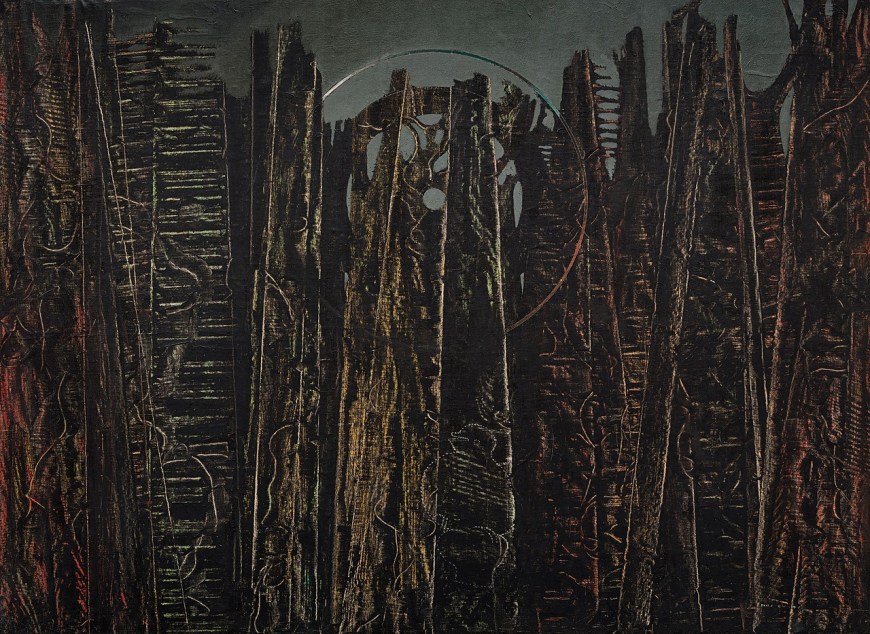

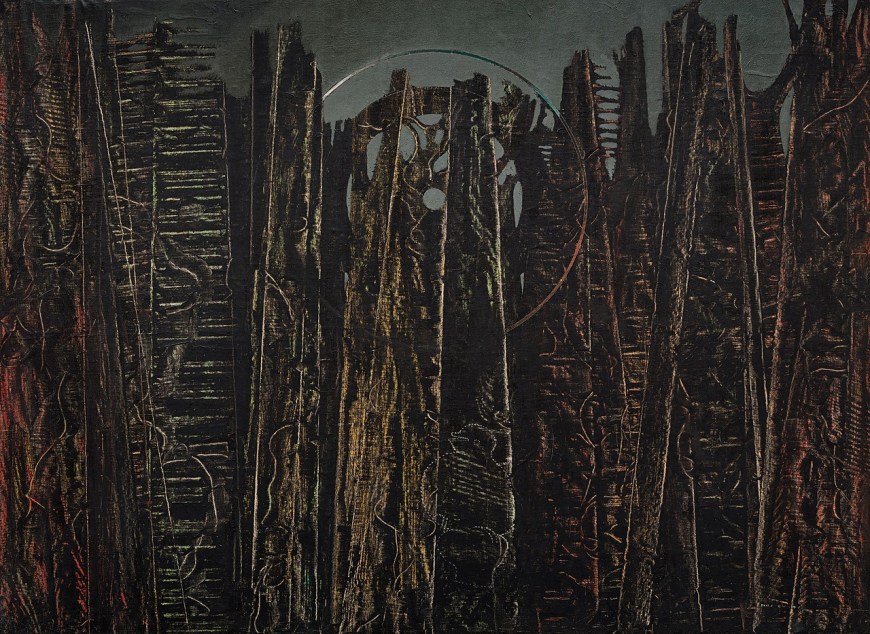

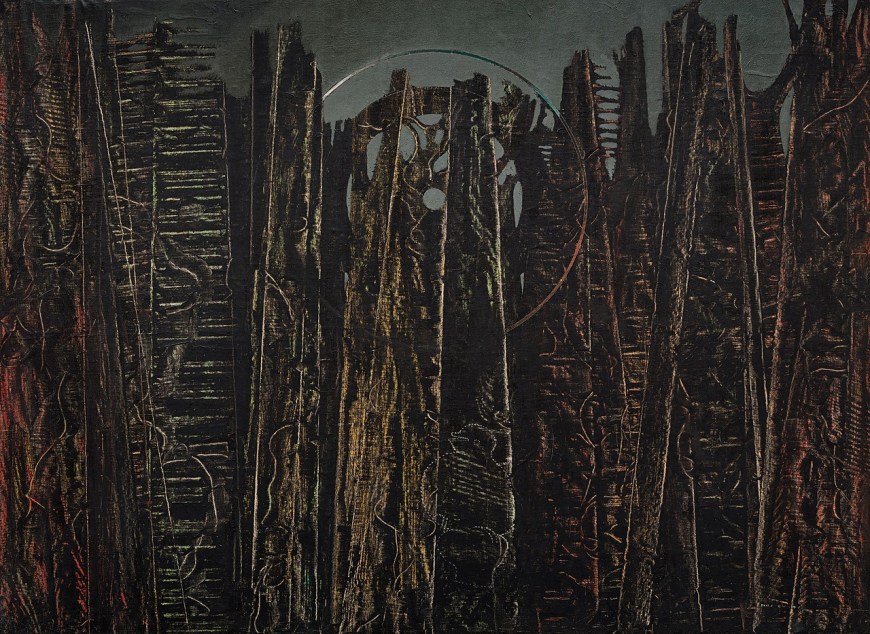

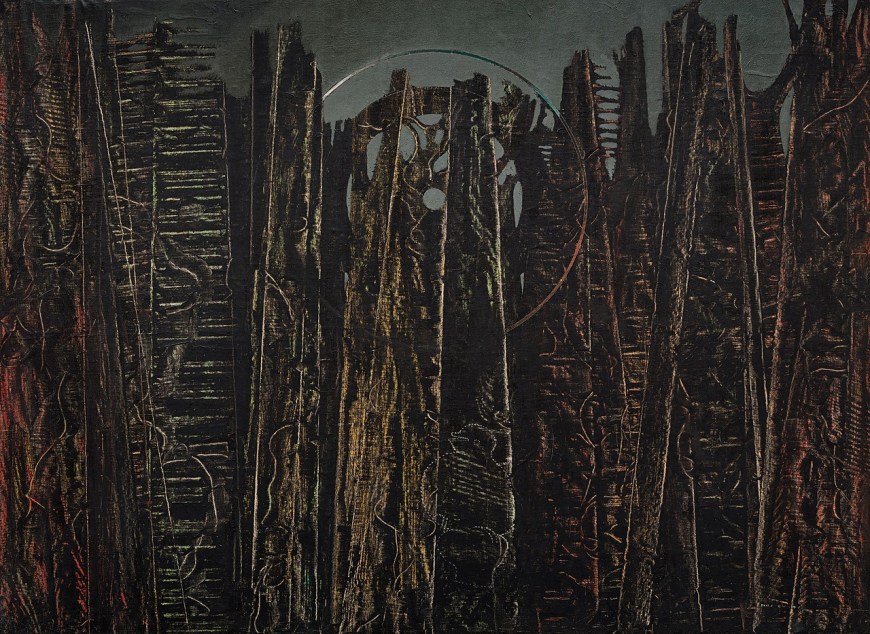

The Forest and Dove is part of a series of images in which Ernst explores his childhood memories about the terrifying, dreamlike places that forests are. In the painting, we see a small bird in some sort of enclosure, trapped between large, dark, and threatening trees. The figures are all very elemental, particularly that of the bird, which bears the simplistic characteristics of a child’s drawing. Ernst created the intimidating shapes of the trees by employing his technique grattage.

So far, it has been established that Ernst used birds as symbols to represent himself. This artwork is likely echoing the artist’s feelings at a time which he spent probing his subconscious. Inside that subconscious, what he found was a sense of entrapment and primordial fear – both echoed in this painting.

The trees surrounding the helpless bird are great, dark forces that the lone creature cannot face on its own. Aside from fear, the imagery denotes feelings of loneliness and isolation. Perhaps the simplest explanation can suffice here: the artist was exploring his childhood fears and memories through dreaming and automatic drawing (a technique the Surrealists popularized as a means of recovering “lost” memories and discovering greater truths), deciding to immortalize those perturbing visions on canvas. The bird is young Max Ernst, engulfed by darkness.

Max Ernst’s Surrealist paintings “are steeped in Freudian metaphor, private mythology, and childhood memories”, as described on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website. His imaginings of birds often contain anthropomorphic elements too. This painting belongs to a series Ernst completed in 1937, which he titled The Barbarians.

We see two gigantic creatures, presumably one female and one male, on an open field. It looks like the pair is on its way to cause chaos. The birdlike figures look more like titans – or even dinosaurs – than they do birds. The darker one on the left (the female), seems to be leading her partner somewhere. Meanwhile, he turns to face a figure reminiscent of an ostrich which is hanging from his left arm. In the distance, below them, a woman is touching an avian figure. Whatever those creatures have in mind, they are about to cause mayhem. The intricate patterns defining their fur, giving them volume and movement, have been achieved by means of Ernst’s favorite technique, grattage.

The avian boogeymen are undoubtedly bad omens with dubious intentions. This is something that becomes evident the moment anyone lays eyes on this painting. However, Max Ernst’s biographer, John Russel, has a more interesting and topical theory with regard to the painting: these terrifying creatures are manifestations of the German artist’s fears regarding the impending catastrophe that would engulf Europe during World War II. Sadly, his fears came true. As for the human woman in the foreground playing with what could be a bird, she might serve as a symbol of hope and survival in a desolate landscape. She and the bird are the ones that managed to escape the monsters’ grip, proving that love might be able to conquer all.

It’s a troubling, glorious thing, this picture. Seeing it in a gallery is like encountering a screaming exotic bird in a cathedral. It is both beautiful and horrible.

– Jonathan Jones.

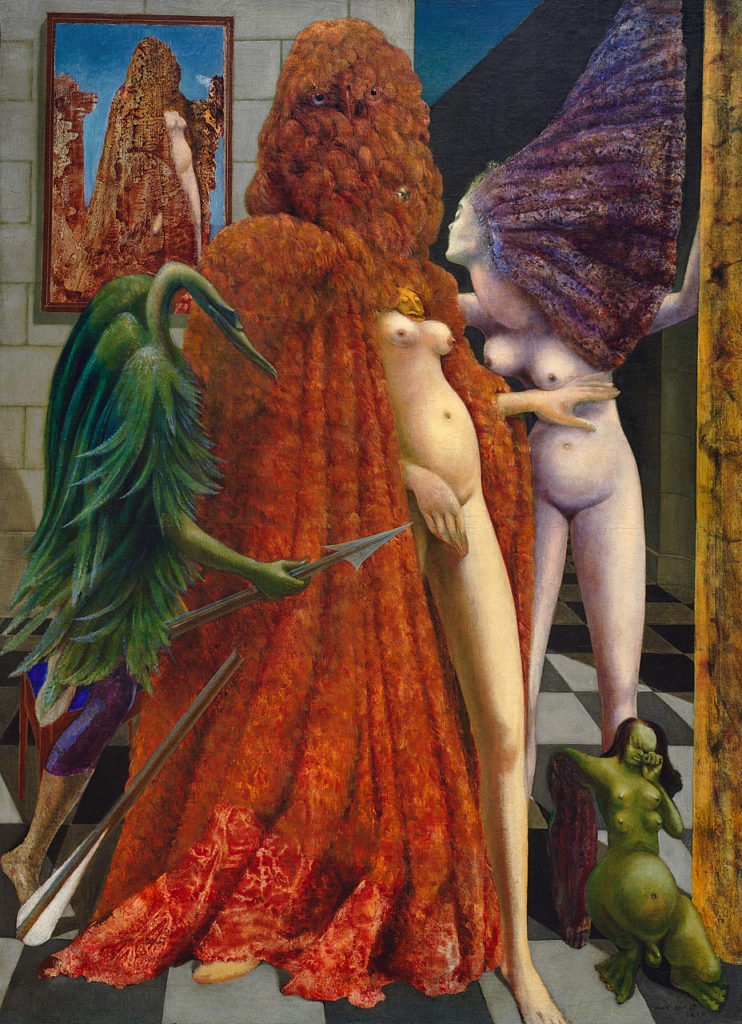

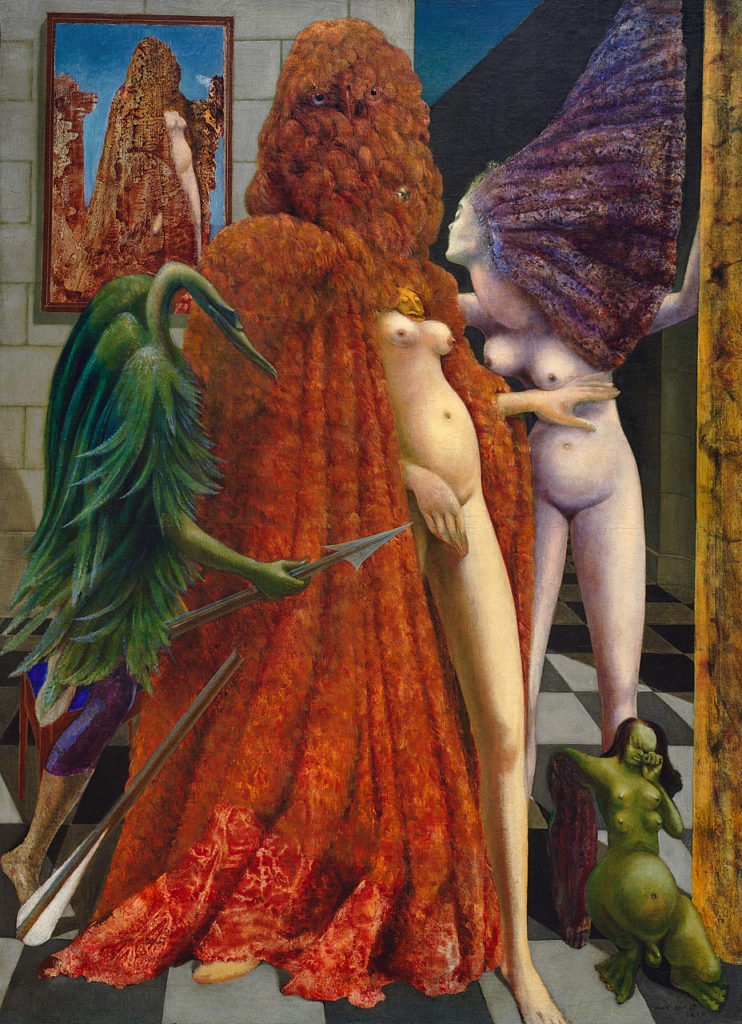

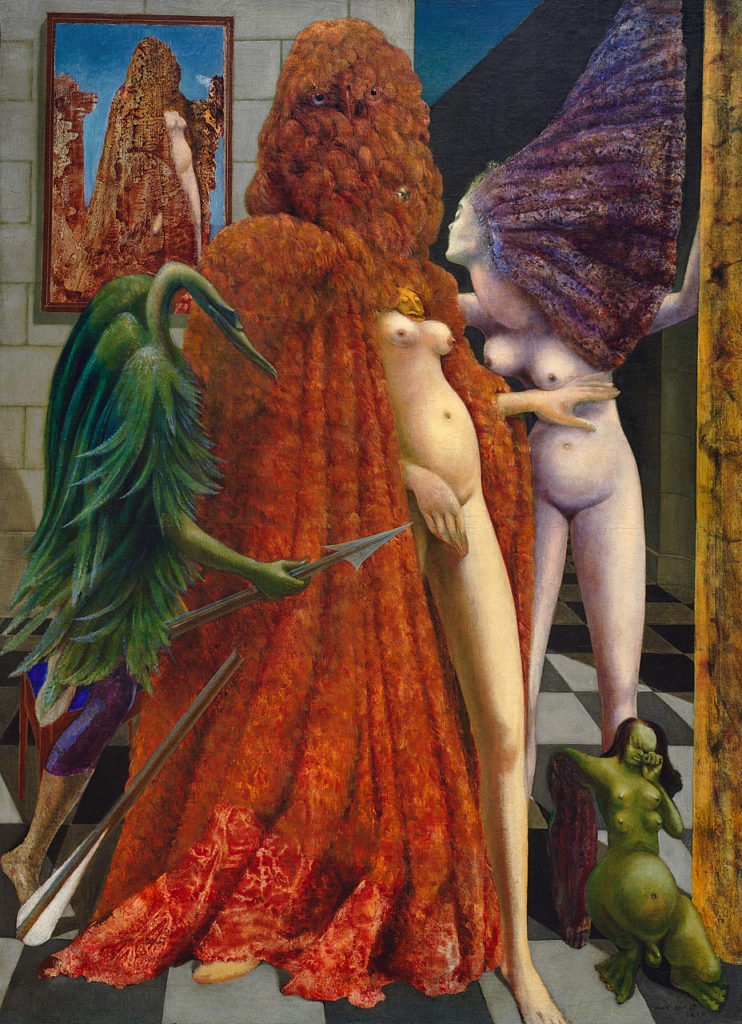

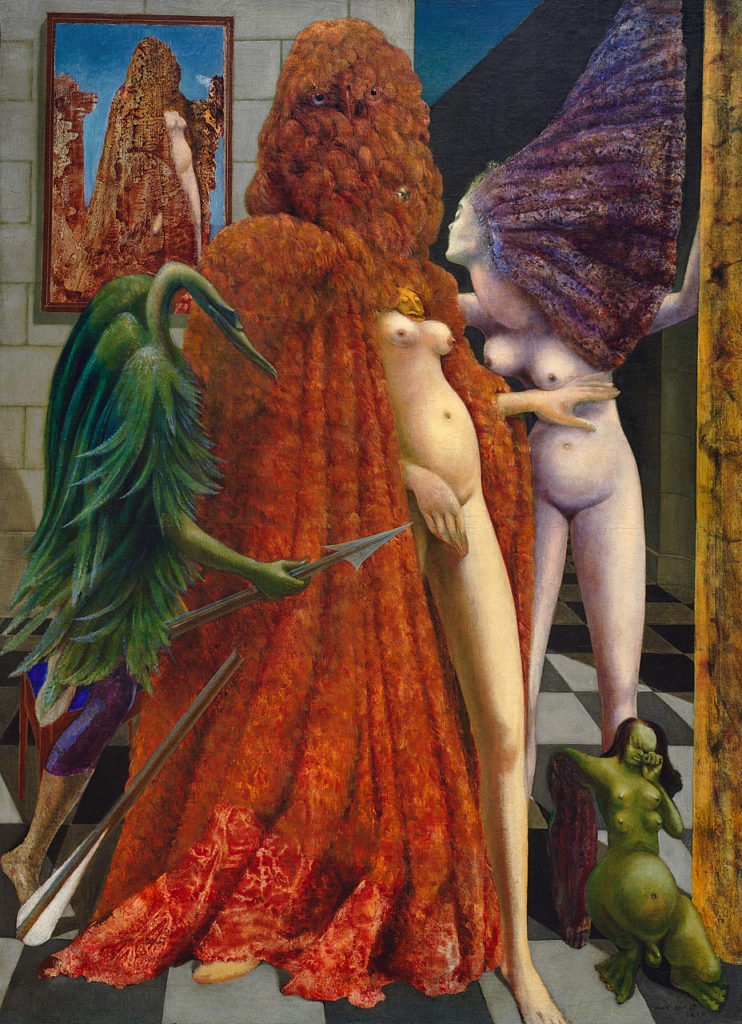

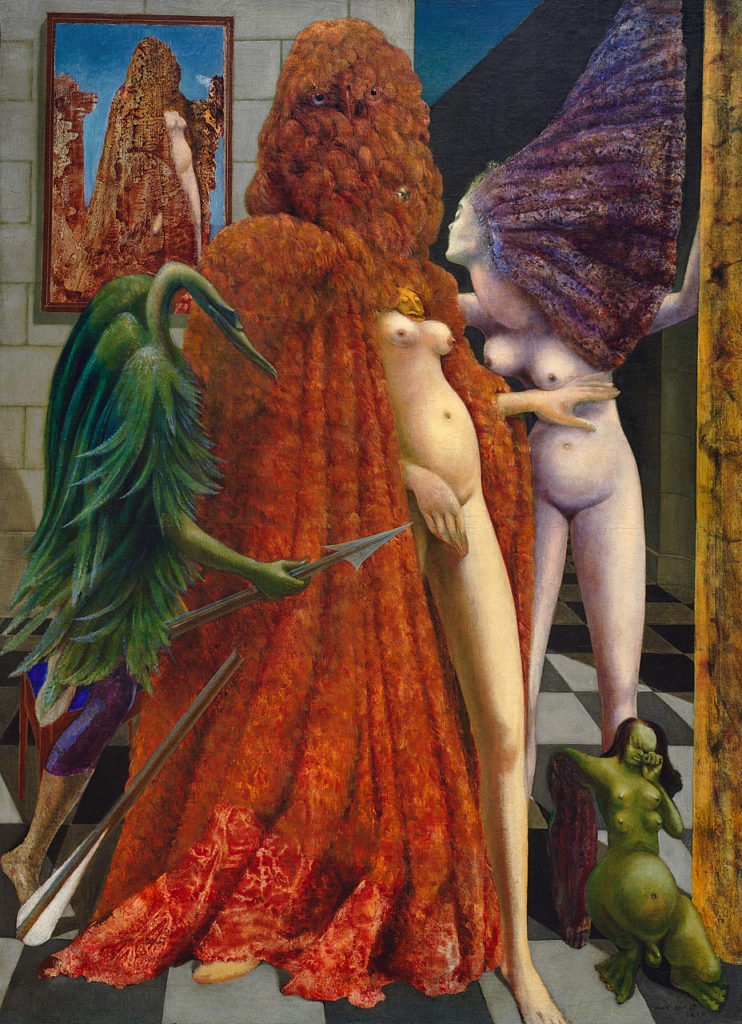

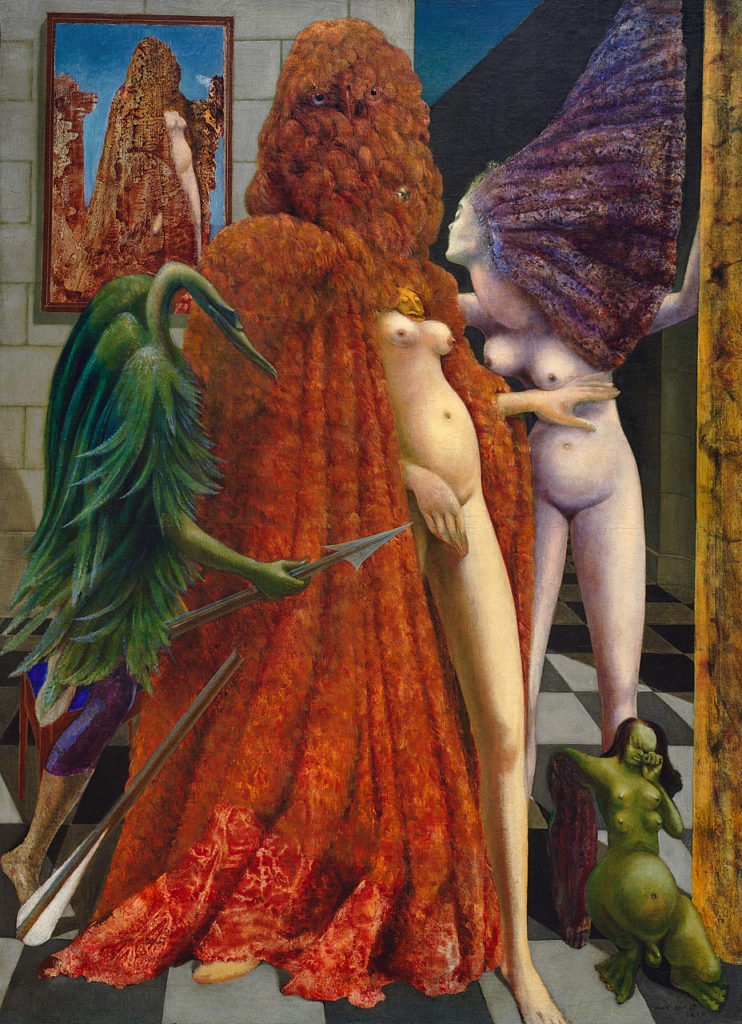

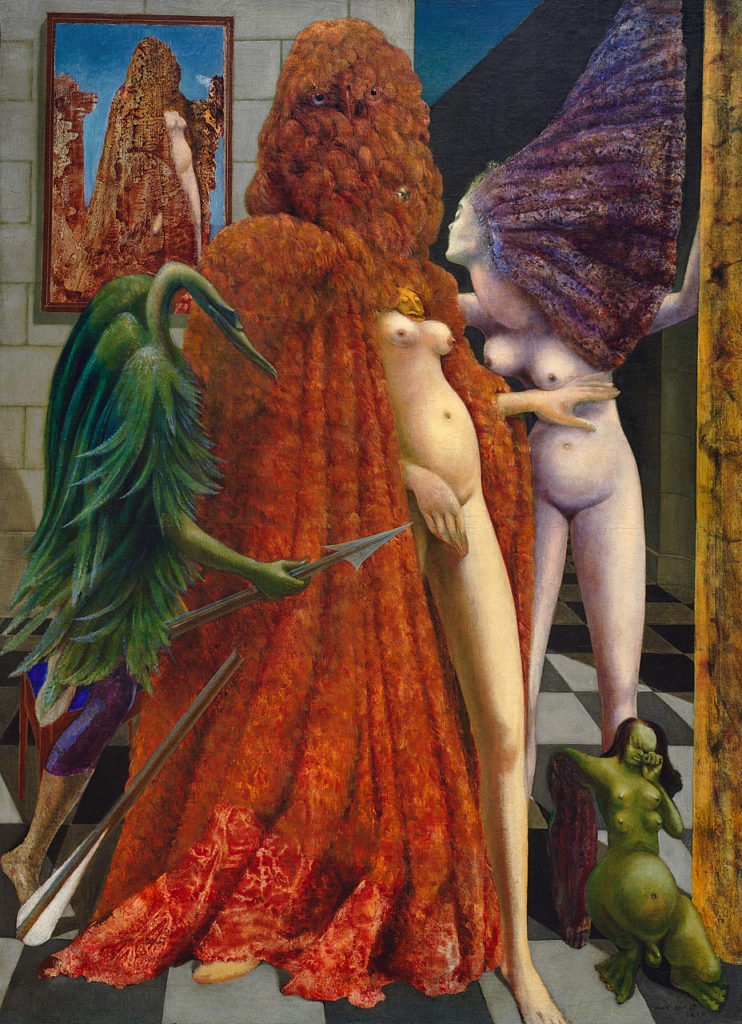

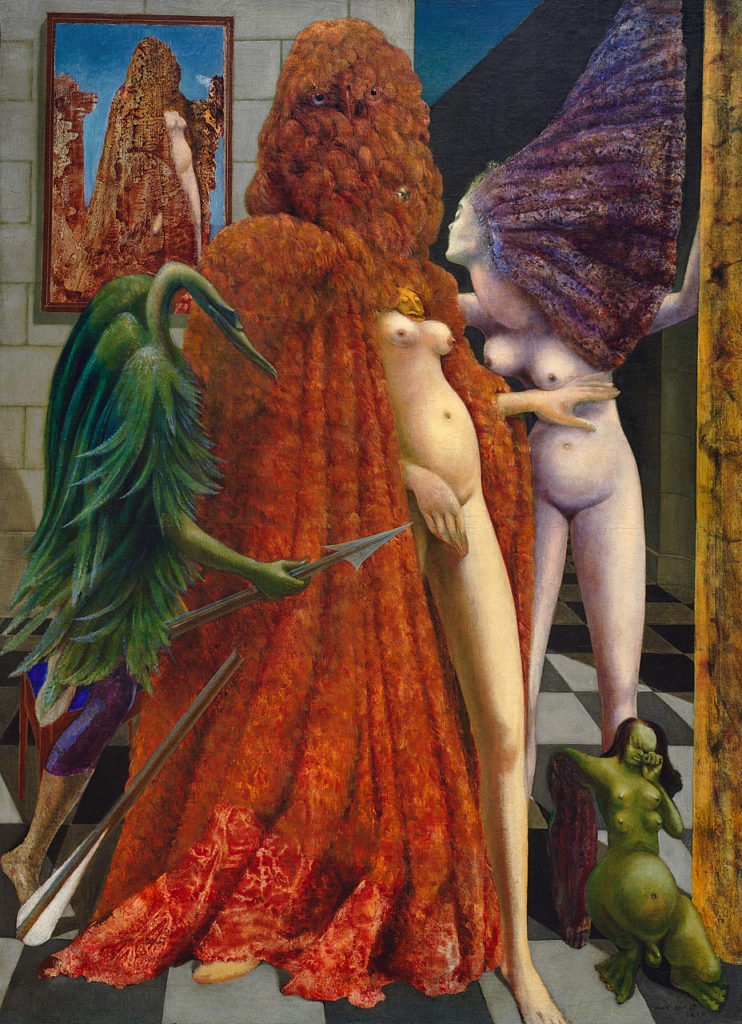

The Robing of the Bride is a prime example of Max Ernst’s illusionistic Surrealism, in which the artist applies a traditional technique to an incongruous or unsettling subject. This is a painting that is rich in imagery and rife with potential explanations.

What we see on this canvas is five humanoid figures in total. The first one is in a framed picture in the background, showing “the bride” exactly as we see her in the foreground of the painting as well. To the right and left of the bride, we see a human-looking female figure and a swan-like green male figure, respectively. In the right-hand corner, we see a hermaphrodite, a humanoid monster.

What each of these figures is doing can offer clues as to what they could potentially mean. The bride, in all her glory, is standing still and posing, wearing a giant bird’s body (Loplop?) as a makeshift cape. It seems to be almost engulfing her. She could be in mid-transformation from human to bird. She seems to be aware of that too, as her avian eyes are staring straight at us with conviction.

The humanoid green bird is looking down towards a spear, clearly a phallic symbol, pointed toward the bride’s pubic area. The bride is touching the mauve-toned woman next to her with her left hand. The naked woman is looking back, possibly at the picture on the wall, and away from the bride. What we can assume to be her hair – which has been structured with the technique of decalcomania, much like the image of the bride hanging on the wall – is standing up. Lastly, the four-breasted monster in the corner is weeping.

All the female figures in the picture are exposing themselves almost completely. All of them also have varying degrees of swollen bellies, with the bride having the smallest, and the defeated green creature the largest. The male figure, on the other hand, is covered with rich plumage, and we can only see his limbs.

The painting has the desired effect, the effect that Ernst wanted it to have, it can be interpreted in a number of different ways. The bird-man on the left of the canvas could be a depiction of the artist himself and the bride may represent Surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, who was in a relationship with Ernst at the time. While this is a reasonable explanation, the painting could also be an allegory for the different stages of married life that a woman undergoes, akin to Gustav Klimt’s The Three Ages of Woman.

First, the woman is an oblivious bride-to-be led on by her husband who is trying to turn her into a bird – something she is not – using his virility to galvanize the bride into action. The next stage is when the wife becomes pregnant. There is little left of the person she was when she first got married. She is catching herself reminiscing about the charming past by looking at pictures. The third stage is birth and motherhood, during which the wife loses her sexuality (or her sexual appeal) and the woman is withering away, as the burden of married life is a heavy one to carry. She is desperately clinging onto a small piece of her past self. The purple object next to the green creature looks like a fragment from a precious stone.

The colors could be functioning as further evidence: red, the color the woman starts out as, is the color of passion and suppleness; lilac is the color of melancholy; and green, the same color as the male bird, is the color of envy.

The fact that all five figures in the painting are touching each other in some way creates a continuous, unbreakable line, reflecting the fluidity in the passage of time within a marriage – though it is not a harmonious fluidity. The Robing of the Bride then, could be interpreted as signifying the taking of a woman. These different stages of a woman’s life are, of course, all told from the perspective of a male artist who dissipated his marriage three different times and got married four.

Stokes states that all surrealist art is, to some degree, meant to be taken as an autobiography of the artist. For surrealists, art is “an avowed codification not only of how artists see the world but of how they see themselves. To make the personal nature of their art explicit, they created individual personas that they included into their works”. Surrealist artists utilized the newly developed techniques from the realm of psychology to conduct research into their own pasts and uncover a unique combination of visual symbols.

Such a persona in the form of Loplop, who was not only the artist’s personal symbol but the presenter of Ernst’s interpretations of his own world.

– Charlotte Stokes.

This approach explains the persistent nature of Loplop’s presence throughout the artist’s oeuvre. However, a progressive shift in the relationship between the artist and his avian persona is notable through these three paintings, created years apart from each other. Max Ernst starts to transition from darker colors to lighter ones. From exclusively painting birds in dystopian landscapes, he eventually starts to allow human figures to take up more and more space in his canvases. Lastly, at the outset of his career, Ernst was focusing on himself and his – conscious or subconscious – worldview. However, through his artistic choices, we can tell that he gradually started to include and take into consideration other people, from the women that were part of his tumultuous love life to his artist friends.

The more independence Max Ernst gained from birds as trademark symbols in his art, the more he seemed to make his art something that a spectator other than himself could try to make sense of. Thereby, we, the audience, can witness the evolution and development of Ernst’s personality through his paintings. Regardless, these are all theories, and every viewer can make of surrealist art what they will. Surrealist artists wanted their art to pose more questions than it answered. Thus, there cannot really be a concrete, certain conclusion on, or solution to, surrealist art. It was never meant to be a solvable mystery.

Jessica Backus, Beyond Painting: The Experimental Techniques of Max Ernst, The Art Genome Project, 2014.

Max Ernst, Forest and Dove, Tate website. Accessed 11 Sep. 2023.

Lucy Flint, Max Ernst, Zoomorphic Couple, The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation website. Accessed 11 Sep. 2023.

Lucy Flint, Max Ernst, Attirement of the Bride, The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation website. Accessed 11 Sep. 2023.

Samantha Friedman, Max Ernst, Museum of Modern Art website. Accessed 11 Sep. 2023.

Jonathan Jones, The Robing of the Bride, Max Ernst (1940), “The Guardian”, 6 December 2003.

J. Fiona Ragheb, Max Ernst’s City with Animals, The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation website. Accessed 11 Sep. 2023.

Charlotte Stokes, Surrealist Persona: Max Ernst’s ‘Loplop, Superior of Birds, “Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art”, vol. 13, no. 3/4, 1983, pp. 225–234. JSTOR.

The Barbarians by Max Ernst, The Metropolitan Museum of Art website. Accessed 11 Sep. 2023.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!