5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

8 December 2023 min Read

The art of the mandala is like a secret language of the soul. It represents both a map of the cosmos and the soul’s progress through meditation toward enlightenment. With an unlimited wealth of motifs and symbolic allusions, mandalas are an indication of our inner or outer experience of the world. Its symbolism unites times and cultures. Once you have traversed the circle, it begins anew, only on a slightly higher spiritual level.

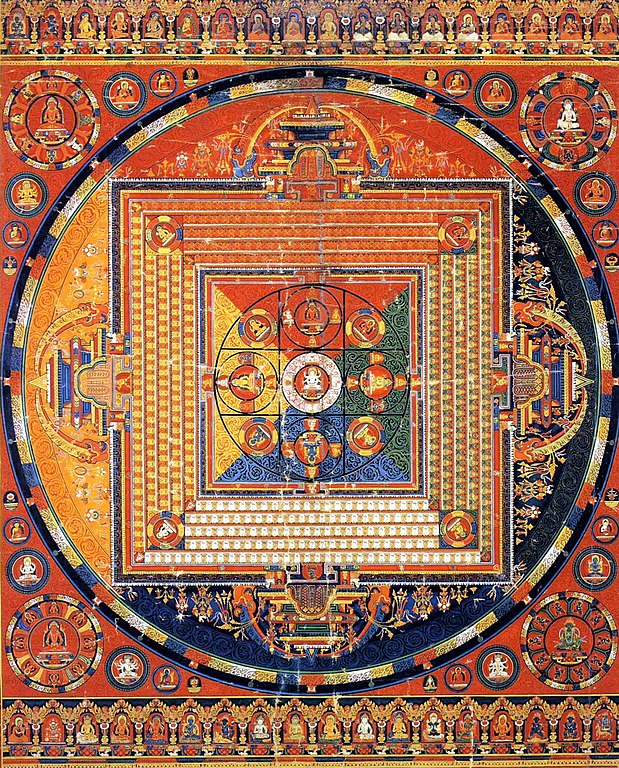

A mandala, which literally means “circle”, is a geometric arrangement of symbols. In a mandala, everything is organized into a rational scheme representing certain relationships. It is laid out on a grid pattern, in a circular form, combining squares and circles. Mandalas are symbols of the cosmic elements, models for visualizations, or aids to meditation on the transcendental. In Buddhism, a mandala is a visual representation of the sacred universe. Thus, mandalas combine representation and an extreme form of symbolism. Although mandalas appear in many cultures and regions, here we will focus on the Buddhist mandala.

In the 7th and 8th centuries, Vajrayana, “Thunderbolt or a Diamond Vehicle”, an esoteric form of Buddhism, emerged. Buddhists believe that humans are reborn until they perfect their karma. Therefore, enlightenment and release from samsara, or the cycle of rebirth, might take countless lifetimes. However, in Vajrayana Buddhism, it is possible to attain enlightenment in a single lifetime. Thus, like a strike of lightning, a devotee could hope to eliminate desire, greed, and other blocks on the path to enlightenment.

We can approach ultimate reality through sensory experiences. For example, bodily experiences through mudras or hand gestures, verbally through mantras, and mentally through mandalas. When practitioners unite themselves with the ultimate Buddha nature through these activities, the illusory barriers between the profane and the sacred are removed and enlightenment is experienced as one transcendent, non-dual reality.

This Sarvavid Vairocana Mandala miniature series served as a guideline for meditating on a mandala. The painting shows what the meditating person builds in his mind. First, he concentrates on the life of the Buddha, clears his mind of interfering thoughts, and enters a peaceful state. Then, he visualizes various aspects of the divine. Finally, he attains a higher level of consciousness whereby he becomes one with the deity, Vairocana.

Thus, esoteric Buddhist practice involves elaborate rituals and special forms of meditation. A guru, or teacher, guides along practitioner on this path. Worshippers also use mystic symbols and secret chants to appeal to a pantheon of deities for help. Furthermore, Buddhist texts describe the spells and rituals, involving consecration in the mandala, required for the invocation of these deities. Feeling togetherness with the deity, practitioners are able to exercise their powers, such as deepening their wisdom and compassion.

Traditionally the mandala is a geometric design, comprised of circles within a square. Usually, it refers to what is held within the circle. Buddhist mandalas are highly ordered structures with little room for artistic freedom though. However, makers of a mandala may slightly vary colors and details, such as depictions of flames or water.

For many Himalayan traditions, the squares of the two-dimensional mandalas are representations of a three-dimensional palace. A two-dimensional painting of a mandala is a bird’s eye view of what this palace would look like. If you visited this place, you would travel through the large outer rings of flames and charnel grounds. Then you would enter the square which is a representation of a palace.

In Tibet, some of the earliest mandalas appeared in the 9th and 10th centuries. In many of these mandalas, as though mimicking the cross-shaped plan, makers arranged deities in a pattern according to the cardinal directions. If you stepped into the innermost circle of a mandala, you would come face to face with a deity who resides within this imagined space.

The mandala is a symbolic representation of the ancient conception of the cosmos. In its center is Mount Meru, the axis mundi or central axis of the physical, metaphysical, and spiritual universe. The earliest appearance of the mountain’s name, Meru, is in the Mahabharata, the great Indian epic.

Mount Meru, also called Sumeru, is the pillar in the center of the world. It penetrates the universe from top to bottom. The wind layer is below and the heavens are above this mountain. Meanwhile, seven rings of mountains separated by seven seas encircle Mount Meru. Many traditional representations portray the mountain ranges as arranged in concentric circles. However, it is a conceptual, not a literal representation of the cosmos.

The mandala also represents the enlightened mind. Within its structure, the outer circle usually symbolizes wisdom. Furthermore, the ring of eight charnel grounds points to the Buddhist notion of always being mindful of death. Inside these rings lie the walls of the mandala palace itself, populated by deities and Buddhas.

The origin of the mandala is not quite clear. However, the earliest concepts may have come from India and were initially mentioned in early Sanskrit texts. They described how the gods may have existed in their worlds. For example, Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom, appears in this sculpture in his esoteric form, with three heads and six arms. The way he crosses his hands at the chest signifies supreme wisdom. Manjushri holds a bow and arrow, a sword, a lotus, and vajras or ritual weapons. Most prominent among the weapons is the sword, which cuts away ignorance.

Five stupas appear above the elaborate architectural setting. Within these stupas sit emanations of Manjushri. This sculpture represents a mandala because it conceptualizes the architectural plan of one of the great Buddhist monastic complexes or mahavihara of Bengal, probably in present-day Bangladesh.

Somapura Mahavihara was one of the important centers of Buddhism. The complex is located in Paharpur, in northern Bangladesh. It was built by king Dharmapala (ca. 781–821) of the Pala dynasty (8th –12th centuries). The original tower in the center of the complex was believed to be about 32 meters (about 105 feet) high. Four large holes were placed around the tower towards the cardinal points. Consequently, the cross-shaped plan of this mahavihara could represent a part of the mandala.

The complex contained all the facilities required for Buddhist training. It was surrounded by 177 small lodging rooms for the monks. The remains of tables for Buddha statues in each room show that monks spent their private time in study and meditation.

In places like Paharpur thinkers probably helped to develop the concept of the Five Tathagatas or Dhyani Buddhas. These deities are “self-born” celestial buddhas who have existed since the beginning of time. In contrast with historical figures like Gautama Buddha, they represent intangible forces and divine principles. These Buddhas usually include Vairocana, Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha, and Amoghasiddhi. Each of them has their own colors, symbols, and mudras. They also face different cardinal directions. As a result, monks found a new way to meditate on self-restraint.

In the ritual practices of Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism, devotees practice the five forms of meditation in order to acquire the five types of wisdom. When Shakyamuni excelled in his practice, he entered samadhi or a state of intense concentration. Finally, he became Buddha Vairocana and, possessing five types of wisdom, he was transformed as the representation of the Five Wisdom Buddhas of the Five Directions.

In the upper half of this thangka, or painting are Five Wisdom Tathagata Buddhas. In the center, we see Vairocana, while in the upper-left corner sits Akshobhya Buddha depicted in blue. Meanwhile, in the upper-right corner, Amitabha appears in red, and Ratnasambhava, in yellow, occupies the lower-left corner. Finally, in the lower right, Amoghasiddhi, in green, completes the circle.

The Vajradhatu (Diamond Realm) Mandala is one of the mandalas with Five Dhyani Buddhas. In Vajrayana Buddhism, the Diamond Realm is a metaphysical space inhabited by the Five Buddhas. The four-faced, eight-armed white Vairocana is in the center of this mandala. Other Buddhas sit at the centers of the four adjacent circles.

Each of these Buddhas offers spiritual tools that can be used on the path to enlightenment. Firstly, Vairocana, teaching the dharma or nature of reality, combats ignorance. Next Akshobhya, in blue, sitting in the east, holds a vajra or a ritual weapon. He provides knowledge to the mortal, creating humility, and reducing aggression. He also symbolizes winter.

Ratnasambhava, in yellow, bestows blessings, giving enrichment, pride, joy, and calmness. His symbol is a jewel and he also represents autumn. Further, Amitabha in the west, depicted in red, helps to define one’s self. With the quality of overpowering mortals, he can be found in the fire. Amoghasiddhi, in green, located in the north, eradicates fear, envy, and jealousy. He delivers courage and wisdom to the mortals and he also signifies the summer.

In four circles marking the intermediate points of the compass are four goddesses associated with offerings made to the mandala’s central deity. The square section of the mandala is like a multi-tiered palace. It is inhabited by two hundred and fifty bodhisattvas associated with each Buddha. Meanwhile, at the four cardinal directions stand gateways in the form of pronged vajras or ritual weapons. Celestial and historical figures associated with the teachings of this mandala appear in the registers. Also, along the base row sit powerful protectors and auspicious gods.

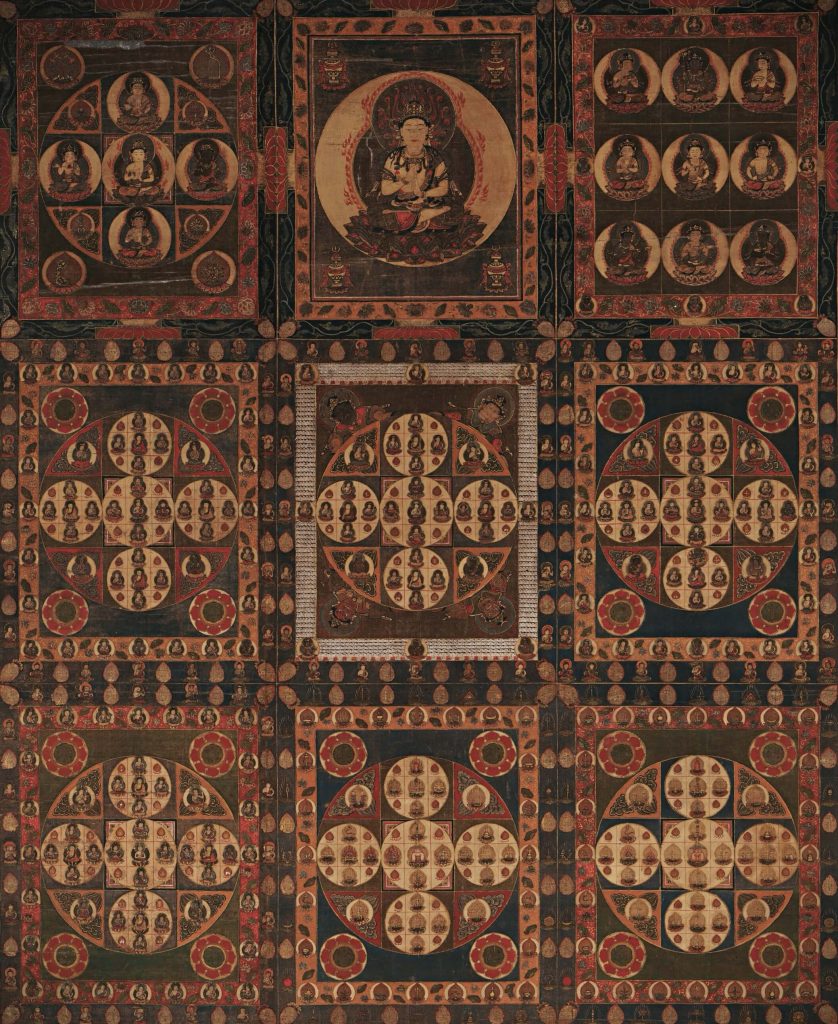

From Tibet, we are transported to China and Japan. In Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, Ryokai or the Mandala of the Two Worlds represents the Buddhist cosmos. It may have first appeared in the eighth century in China. In 805, a Chinese Buddhist monk, Huiguo, explained the meaning of this mandala to his Japanese disciple Kukai, known as Kobo Daishi. Kukai then introduced the pair of mandalas to Japan. Consequently, they became one of the canonical foundations for his new Shingon sect.

The first, the Diamond World mandala, represents reality in the Buddha realm. It is the world of the unconditioned, the real, the universal, and the absolute. Meanwhile, the Womb World mandala signifies reality as it is revealed in the world of the conditioned and the relative. However, each mandala is fully meaningful only when paired with the other. Therefore this kind of set often hangs on facing walls in the temple hall, offering the means to reveal the ultimate truth.

The Diamond World, or kongokai mandala is composed of nine near squares. Within each square is a mandala in its own right. Here, Vairocana, or Dainichi in Japanese, appears in a state of infinite, all-encompassing wisdom. He is the Supreme Buddha of the Cosmos from which the entire universe emanates. He also sits in the top middle assembly.

The central lighter square assembly of the entire mandala is the basis for meditations leading to the attainment of Buddhahood. Furthermore, the eight squares that surround the central square are variations on this basic message. A directional Buddha attended by four bodhisattvas occupies the circle within the square. Dainichi, embodying perfect knowledge, sits in the epicenter.

The four directional Buddhas in the center of each circle express four aspects of Dainichi’s complete and perfect knowledge. Thus the five Buddhas point to the five dimensions of wisdom and signify the realization of enlightenment. In due course, four attendant bodhisattvas represent stages in the development of Buddhahood after the initial attainment of enlightenment.

In the corners of the first square are the deities symbolizing earth, water, fire, and wind. These four gods represent four of the five elements that form Dainichi’s unmanifested, “inconceivable” or reality body. The middle square has tiny representations of the thousand Buddhas, two hundred and fifty in each of the four directions. Twenty guardian figures also appear at the edge of the outer enclosing square. This reciprocal relationship thus leads to the emergence of these deities. In a way, it is similar to the activity between a practitioner and a deity who realize their essential nonduality in merging body, speech, and mind.

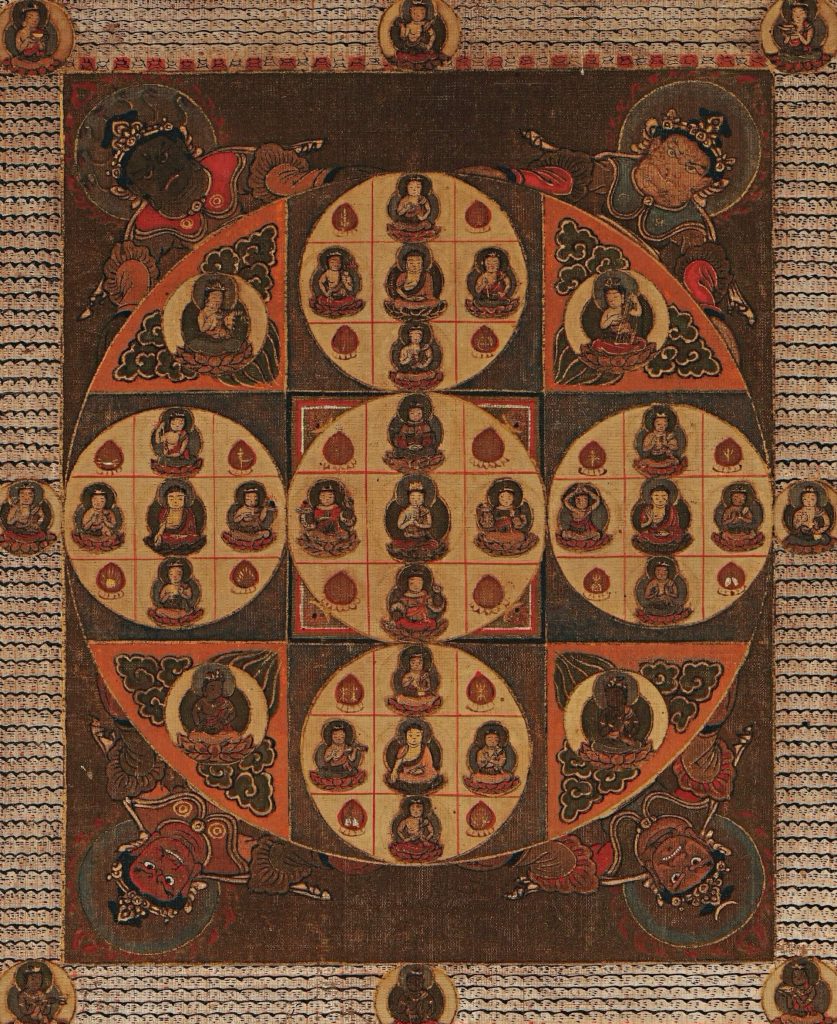

The taizokai, Womb World or Matrix Mandala represents the second realm of the Two Worlds. The large central flower of taizokai is a lotus. It is a Buddhist symbol of purity. Furthermore, in the Womb World mandala, it also signifies compassion. The “lotus womb” concept emphasizes that various phenomena exist in their entirety before they have come to fruition. The womb is the source of the birth of things. Great compassion produces this mandala. At the same time, great compassion is created from this mandala.

The cosmic Buddha Dainichi sits in the epicenter of the mandala. His great compassion causes the radiating outward of every aspect of the universe. The Buddhas of the four directions surround Dainichi. They represent four stages in the attainment of perfect Buddhahood.

Then, the four great bodhisattvas are seated in petals between the four directional buddhas. They embody the practices on the way to enlightenment. More than four hundred figures appear in the eleven sectors that surround the central hall. The bodhisattvas, monks, and deities symbolize spiritual phenomena, such as virtue or meditation. Sacred figures represent the physical world: the stars, wind, earth, water, and fire. They are placed in a generally descending order of sanctity as they approach the outer edge.

Beings from the lowest levels of existence, such as hungry ghosts and demonic creatures, are in the outermost bordering hall. They have not been included in the aura of Dainichi’s radiating compassion, but for them, there is a promise of salvation. Practitioners reach the next level in their meditation, the Matrix is “reloaded,” and they are able to progress on the path toward enlightenment.

Although the Hevajra mandala is different from the Ryokai mandala, compassion is one of its main themes. This mandala is based on the Hevajra Tantra, a text revered by the Sakya School of Tibetan Buddhism. The principal deity, Hevajra, appears with blue skin, three heads, and four arms. He embraces his consort, Nairatmya, at the intersection of four vajra gateways. They stand in a dancing posture at the center of the cosmos.

The Nairatmya’s name means “she who has no self”. This deity embodies the Buddhist concept of anatman. It states that there is no unchanging, permanent self, soul, or essence in phenomena. In due course, Hevajra’s name consists of two syllables. The first one is “he” or compassion and represents the male aspect. The second one, “vajra”, refers to wisdom, the female aspect. Their union offers a path beyond the illusory world.

Both deities have repeating skulls, alluding to the death and impermanence of all phenomena. Hevajra also stands atop a corpse, trampling ignorance on the path to enlightenment. Further, eight deities of various colors are in the lotus petals, standing in a dancing posture with skull cups, surround two central figures. The square palace walls enclose the stylized lotus. The arches, meeting at each gateway, represent the ends of double vajras or ritual lightning balls. On the outer circle, beyond the celestial palace, there are eight great charnel grounds where dead bodies were cremated. A yogic master or mahasiddha presides over each ground.

Mandalas can be created in different media. They may be painted on a wall, cloth, or on paper. Occasionally they are rendered through sand painting or in other sculpted materials. For example, this grain mandala set consists of five silver repoussé components. They are stacked together with quantities of small particles of rice, barley, or other grains. Collectively they symbolize the offering of the entire universe in the ritual known as the mandala offering. Overall the base, three rings, and finial represent Mount Meru and its surrounding universe. The four continents and their associated eight subcontinents appear on the base.

Between the groups of continents and subcontinents are the four sources of endless wealth, such as the jewel mountain, the wish-granting tree, and the uncultivated harvest, which regenerates itself. The first open ring has the seven emblems of royalty, along with the vase of endless treasure.

The next ring depicts the eight offering goddesses. They are the goddesses of beauty, garlands, song, dance, flowers, incense, light, and perfume. The smallest ring has images of the sun, moon, precious parasol, and victory banner. The finial contains auspicious symbols, including the endless knot, the wheel of the Buddhist teachings, and the parasol.

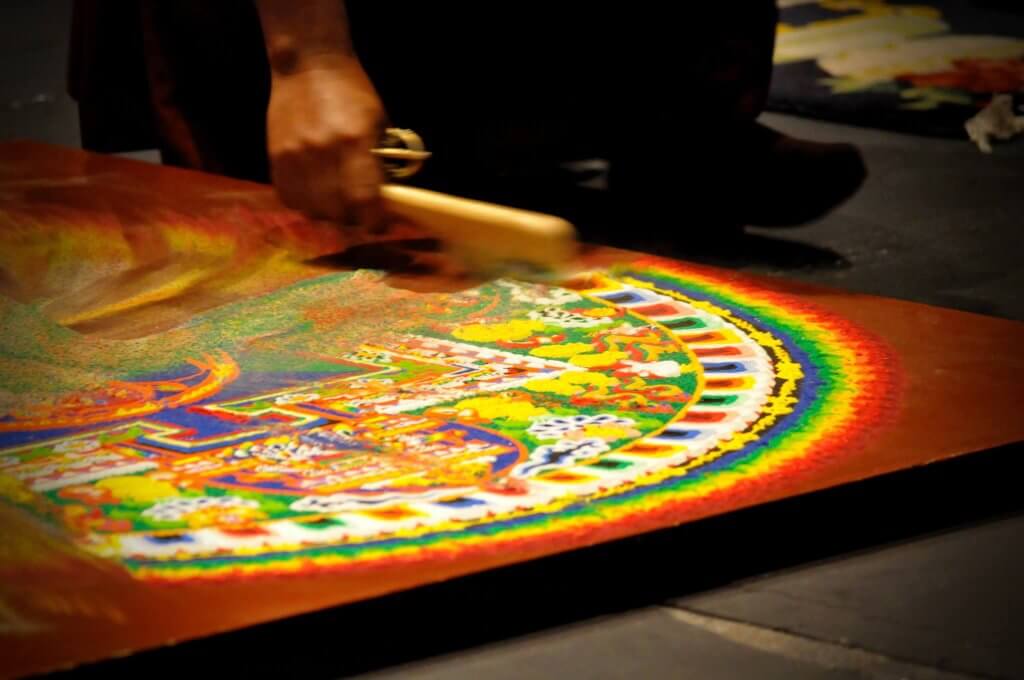

Artists and monks can create mandalas in sculptural and architectural forms. They may also paint mandalas on a wall, cloth, or paper. For example, for ceremonies, monks often create mandalas in less permanent media, with colored powders or sands. They put a lot of effort into producing mandalas. Performing a series of rituals, they prepare the space and objects used to create a mandala. These rituals may take up to three days to complete. Then the makers create a mandala in their minds before they begin the physical creation of the mandala.

When the initiation begins, initiate monks wear an elaborate headdress. It serves as an aid in a ceremonial projection of becoming one with the central deity of the mandala. By placing the bases around the mandala, the initiate prepares the space around the mandala for the deity to reside in during the ceremony. Thus, these initiations help to purify and cleanse the body, speech, and mind of the participant, and to guide him or her into the spiritual awakening.

The construction of a mandala is a part of the ritual. It includes chanting mantras or words of power. The ritual serves for the empowerment of the mandala seen as an object of cosmic energy. When practitioners meditate with a mandala, they access the energy that the mandala embodies.

The actual construction of the mandala is the last phase of ritual preparation. First, monks snap the dry cord or wisdom thread. Next, the deities and their consorts are invoked and dissolved into the string. The monks twist out the cord of five different colored threads that symbolize the wisdom-knowledge of each of the five Buddhas.

At this point, the coloring of the mandala begins. The master sprinkles the first line, the east wall of the mind mandala. Four monks slowly shape the whole mandala starting from the center. For sprinkling, they use fine tools, such as tubular funnels. As a visual aid, the monks employ iconometric handbooks that depict the most important figures and ornaments. The colors for the mandala can come from the natural sand of the Himalayas, mixed with pigments such as yellow ochre, charcoal, or red sandstone. Monks can also use flower pollen, powdered roots, or bark as coloring agents.

The deconstruction of a sand mandala reinforces the idea that everything is temporary. To retain the images is to encourage clinging and craving, which are counter to Buddhist teachings since they lead to frustration and suffering. It is only through letting go or embracing detachment that the journey to enlightenment can begin.

For special occasions, monks work together for days to make a mandala out of colored sand. They meticulously drop sand in fine lines and tiny shapes to create a mandala. Once the monks complete the work of art, they pray and meditate. Then a chief monk disperses the sand, as a sign of transience and non-attachment. By tradition the practitioners offer the sand to a river, mindful of the one that flowed alongside the Buddha’s resting place when he reached enlightenment.

Mandalas are beautiful works of art. They also aid in the exploration of deep and divine concepts. Initiation rituals help to define the sacred space of a mandala. They come with a beautiful set of highly symbolic accessories. Before the mandala ritual takes place, practitioners use the tantric hand dagger to eliminate negative forces that may inhabit the space.

Mandalas often serve as spiritual aids in meditation or initiation rites. Devotees use mandalas not only in teaching but also in training. Their various areas are the abodes of many deities, Buddhas, and Bodhisattvas. Therefore a monk, initiated into secret teachings, may meditate upon and assume the gestures of each deity in the mandala, gradually working outwards from the center. In this way, he absorbs some of each deity’s powers. The practitioner’s goal is to realize within themselves the central force that sustains the universe.

A cosmic mandala recounting the Buddha’s path to enlightenment and referencing the physical geography resonates with his presence. Therefore, the devotee can embark on a metaphorical journey through meditation on images of the Buddha. Many followers believe that this practice can generate great merit and profitable rebirth. In that sense the image itself becomes a kind of mandala, offering a means of understanding Buddhist dharma and thus an expedited path to enlightenment.

Furthermore, a mandala can help the practitioner in meditation. First, he or she invites a deity to take a seat in a place in front of him or her. The meditator visualizes the scene and presents the deity with offerings such as ornaments, music, perfume, or flowers. Then the practitioner confesses his or her faults, takes refuge in the deity, prays, and cultivates the four virtues. These include loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and calmness.

After making the vows, the practitioner removes the curtain from the mandala. Then, dressed as a deity, he or she is ready to enter the mandala in visualization. The master, associated with the emanation of the principal deity of the mandala, leads the blindfolded practitioner who makes numerous vows.

Then, the meditator enters the mandala with his master by the east gate and goes around the mandala three times. Back in front of the east gate, he transforms himself into the deity depicted in the center of the mandala. Thus, following a complex sequence, the practitioner travels through the mandala.

When the practitioner removes the blindfold, a color briefly appears to the master, who gives him the information on the kind of Buddha-activity his disciple should practice. One disciple, acting on behalf of all the others, puts a flower onto the mandala, or a diagram symbolizing it. From the position of the flower, the master sees which Buddha the disciple has a special relationship with.

After these steps, the practitioner takes off the blindfold and sees the entire mandala. These initiations purify the disciple. The deities help the practitioner to experience the mind of clear light and open him to the sorrows of all living beings.

Thus the mandala serves to restore a previously existing order. It also gives expression and form to something that does not yet exist, something new and unique. The basic principle of a mandala becomes very simple, that everything is related to everything else.

Watch Tibetan monks from Drepung Loseling Monastery construct a mandala with colored sand over the course of five days.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!