The (Real) History of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving brings families together to share rich meals featuring turkey, stuffing, and seasonal décor like pumpkins and warm autumn colors.

Errika Gerakiti 28 November 2024

3 July 2020 min Read

During walks through the halls of museums, few people think about how these art masterpieces were not always in their place. In turbulent war years, art, like the civilian population, had to be evacuated. How was that even possible at the world’s most terrifying time? Let’s look at some examples of art’s salvation during World War II!

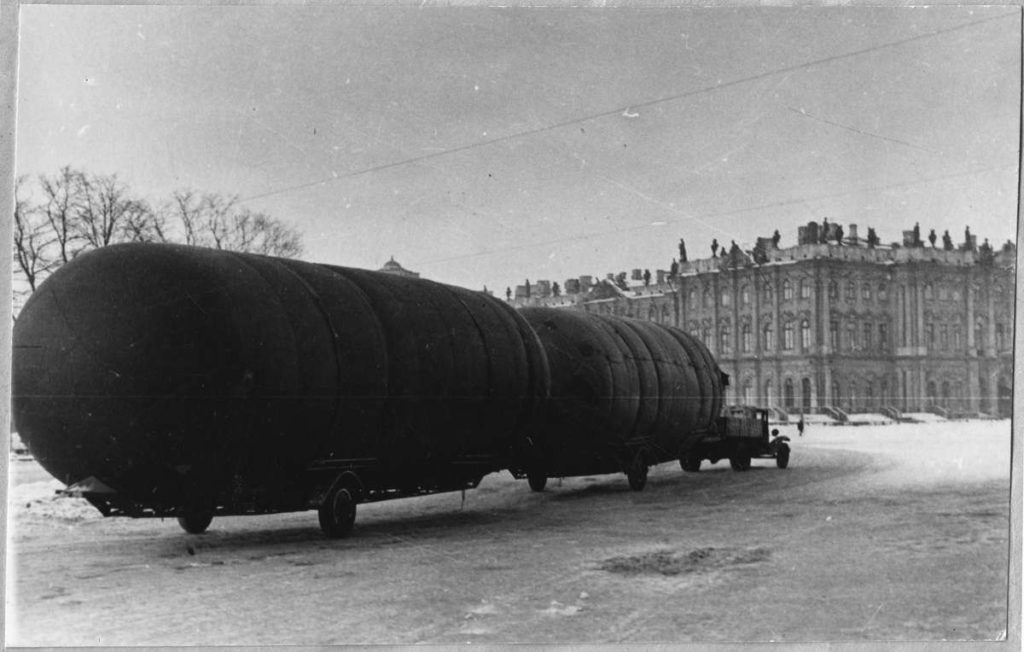

There have been three evacuations in the history of the State Hermitage Museum: one in 1812, one in 1917, and the largest one in 1941. We know very little about the first one, the operation was top secret. In the lists, there are only inventory numbers, without names of the exhibits.

In 1941, packaging began on June 23rd, 1941. On the eve of June 22nd, the day of the declaration of War, the Hermitage director, Joseph Orbeli, gathered the staff and canceled all their days off work (imagine what they must have thought). They worked day and night and used the auditorium of the Hermitage Theater as a place for sleep and relaxation.

In fact, preparations for this evacuation began in 1939, after the outbreak of World War II. In the interim people prepared boxes and stored packaging material in a separate building. Therefore, by the beginning of World War II, almost everything was ready. All that remained was to begin packing.

On July 1st, the first echelon of the Hermitage collection went to Sverdlovsk, followed by the second one on July 23rd. The third echelon was ready too, but the blockade was already closed.

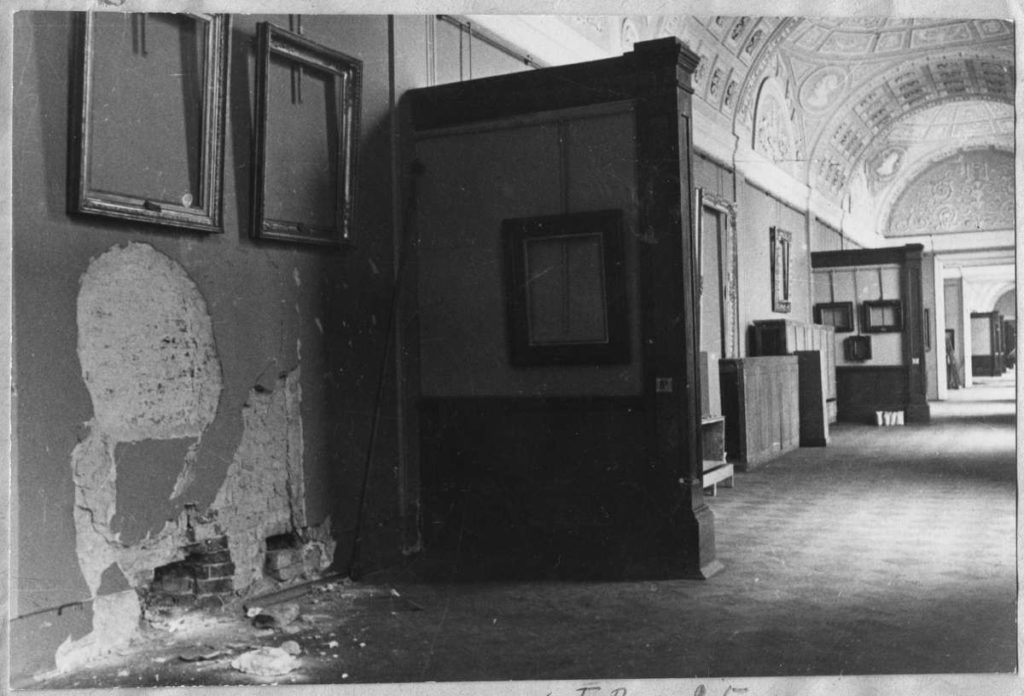

In 1944, an exhibition of unsent exhibits was arranged at the Hermitage. For Leningrad residents, the Hermitage exhibition has become a symbol of rebirth. During the restoration of the gallery in 1945, the first hall to open was the Rembrandt Hall. The Rembrandt collection in the Hermitage was the largest in the world until the 1930s. It was a peculiar sign: Rembrandt came back to the place while the Hermitage begins its life again.

In fact, we can only talk about one serious loss during the War: Anthony van Dyck’s painting, Saint Sebastian. Today its fate is unknown. Maybe you have an idea?

Some works of art in World War II, from the collection of the State Russian Museum, had to be hidden underground. Their transportation was an almost impossible task because of their massiveness. For example, the huge Rastrelli sculpture, Anna Ioannovna with a Little Negro Boy, was buried in a deep foundation pit, located in front of the entrance to the main building of the museum. The figure of Anna Ioannovna was carefully greased first and then tightly packed in ruberoid. For greater safety, a flowerbed was put in at the shelter site. Flowers are always a good idea!

In order to safely transport the largest paintings of the Russian Museum such as The Last Day of Pompeii by Brullov, and Christ and the Adulteress (Who Is Without Sin?) by Polenov, it was necessary to densely roll them on special shafts. This had to be done very carefully to avoid the appearance of “wrinkles”, otherwise the paint layer could be damaged during transportation.

In Moscow, evacuation began almost immediately after the announcement of the invasion of the territory of the USSR. The exhibits of the Tretyakov Gallery and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts were packed the same way as those of the Hermitage.

Most of the collection went to the Novosibirsk Opera and Ballet Theater for preservation. Surprisingly, works of art found viewers even during the war years. From the end of 1941 to the fall of 1944, about 20 exhibitions took place in Siberia showcasing art from the Tretyakov Gallery.

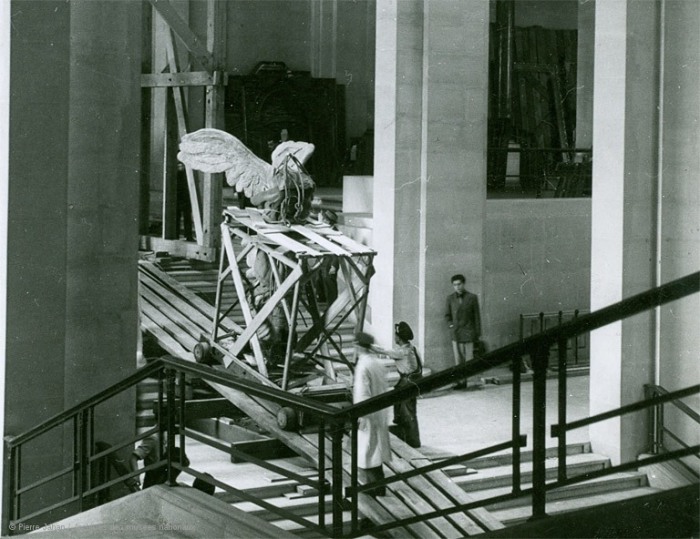

Less than ten days before the start of World War II, the director of the Paris Museum, Jacques Jaujard, organized a secret evacuation of the museum’s art. On August 25th, 1939, the Louvre closed for three days, supposedly for repair work. During this time, hundreds of museum employees and department store workers relocated art in white wooden boxes in the neighborhood. Among them were the famous Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci and the ancient Greek statue of Nike of Samothrace. Before being evacuated they were carefully wrapped in several layers of waterproof paper.

During the occupation, works of art found a temporary home in quiet places in the French countryside, protected from possible bombing. Works that could not be removed were plundered by German occupiers. Middle Eastern antiquities disappeared in large numbers, although most of them returned to their place after the war when the reconstruction of the museum began.

The main attraction of Krakow, the Veit Stoss altarpiece, had not left its place for 450 years. For its evacuation in 1940, it was dismantled into more than two thousand parts, all wrapped in wastepaper, and put into wooden boxes. The largest (13 meters) statues of the saints sailed on barges to the Sandomierz Cathedral. Secret vaults gave shelter to the rest of it. However, the Nazis quickly got on the trail of the altar and took it to Germany the same year.

Karol Estreicher Junior, a Polish art historian could not tolerate this and did not rest until the masterpiece was returned to Poland. The altar was found in the dungeons of Nuremberg Castle. Veit Stoss’ Gothic creation, slightly damaged by moisture and insects, returned to Poland in 1946 in four wagons and one hundred and seven drawers in the company of Lady with an Ermine by Da Vinci. Cheering crowds greeted the returning masterpiece at the train station in Krakow.

After receiving an order to prepare for the evacuation, the State Historical Museum began packing up valuable exhibits: the sabers of Prince Pozharsky, the caftan of Ivan the Terrible, the dress of Catherine the Great and more. Models and copies replaced genuine objects of art on display. Part of the collection was moved to the basement. In late July, a barge carrying the collections of several museums and libraries took the art to Kustanai (Kazakhstan), where it remained until 1944.

The amazing thing was that the historical museum worked for visitors throughout the war. Employees continued to search for artifacts for future exhibitions, primarily collecting documentary evidence of the war such as military uniforms and weapons, posters, and photographs. Museum workers traveled with lectures to the front-line zones, performed at enterprises, and in hospitals. When Soviet troops went on the offensive, employees of the Historical Museum went to the battlefield where they also collected exhibits and recorded witnesses’ stories.

Art in World War II, was under attack not only in famous museums. For example, let’s look at the Prinzhorn collection. German doctor, Hans Prinzhorn, started his practice at the Heidelberg University Psychiatric Hospital in the years following World War I. He became interested in the art of the mentally ill so he collected their paintings and drawings. Everyone saw them as a manifestation of “degenerative” art, which goes beyond the ideas of perfection. Later, such creativity got a name: naive art or primitivism. The Nazis destroyed part of the collection, about 5,000 images from 450 patients. Fortunately, part of the collection that was hidden in the university repository, survived the war and is now on permanent display in the clinic.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!