Fête nationale or 14 Juillet are the official names of Bastille Day in France. This national French holiday commemorates the beginning of the French Revolution of 1789. Let’s see how French artists have celebrated it in their paintings.

30th of June or 14th of July?

Monet’s piece is to confuse you from the start! Many people think that this painting documents a 14th July celebration, but actually the 14th July as the French National Day was proclaimed in 1880, two years after this work had been painted. Hence, it documents a different occasion. A festival which occurred on the 30th June was declared in the same year as the third Universal Exhibition in Paris.

Celebrating “peace and work”, it was intended to demonstrate France’s recovery from its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. As well as showing the strength of the Republican regime after the confrontations between the Government and the Conservatives of 1876-1877. Monet’s impressionistic brush perfectly renders the vibrancy of the moment, capturing the movement of the flags and the people, one can almost hear the whirring sounds.

First official Bastille Day

The date of the 14th July also marked another important event, the fête de la Fédération, which took place a year after the fall of the Bastille prison. It was created to show the unity of the French nation and mark the constitutional monarchy in France. In order to ingrain the newly established holiday, the Government commissioned various artists to create new national symbols.

One of them was a sculpture of Marianne, a female figure personifying the values for which France stood: liberty, fraternity, reason and equality. Her sculpture, entitled The Statue of the Republic was made by Léopold Morice in 1880 and erected on the Place de la République the same year (although it was not the final version but a plaster model, you can see it in the painting).

The Government wanted to document this historic moment, hence they commissioned a canvas from Alfred-Philippe Roll. He did an impressive job, painting a huge panorama (63 square metres) that captured working-class joy. He completed the work for the Salon of 1882 subsequently donating it to the City of Paris in 1884.

Seen through a foreigner’s eyes

Frederick Childe Hassam was American but he spent a lot of time touring Europe. He and his wife eventually moved to Paris for a couple of years. She ran the household, and he found an occupation in illustration. They rented a studio flat near Place Pigalle, which back then was the heart of the art boheme. Hassam’s Parisian works were mostly street scenes in browns, which he often sent back to Boston for sale. In this work we can see how these omnipresent browns make the patriotic tricolor stand out even more.

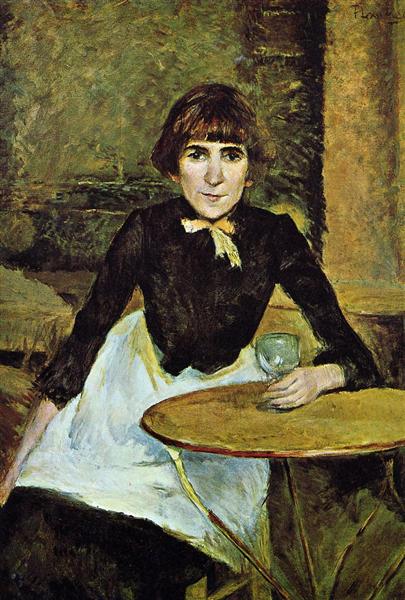

La Bastille Bar

Bastille has its own square and many bars and bakeries are named after the famous prison. At the time of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, there was a famous bar, La Bastille, which inspired famous Parisian chansonnier Aristide Bruant to write a song. It was about a waitress (femme de brasserie) with large brown eyes, who every evening served drinks there. Lautrec cast his friend Jeanne Wenz in the role of the waitress, and depicted the loneliness and rather tragic fate of the song’s heroine.

But why Bastille?

Just a short note on why Bastille has become such an iconic place and name. Built in the medieval 14th century, the Bastille had been a fortress which had witnessed the Hundred Years’ War, the French wars of religion, the Fronde (a series of civil wars) and ultimately the French Revolution. It had always represented royal authority and power, and at a time of growing social unrest during the 18th century, it naturally came to symbolize the abuse of power by the monarchy. Hence, on the of 14th July 1789, the partisans stormed the prison,(which at the time contained only seven inmates). And once the prison had fallen into hands of the revolutionaries: the French Revolution had begun!

Find more paintings depicting important historical events in: