Skiing in Art History

Artists have long captured the magic of snow. During the 19th century, when winter sports like skiing, skating, and sledding became more popular in...

Louisa Mahoney 31 January 2024

The history of Chinese sports can be traced back thousands of years, revealing many achievements, innovations, and surprises. While some sports may seem contemporary, they have roots in ancient China. Take football, for instance—the Chinese could very well have pioneered the world’s inaugural inflated ball game. Similarly, golf might have been practiced in a rudimentary form long before its introduction to the West. Additionally, their early polo matches marked victories for participants, and street gymnasts proved a prime source of entertainment.

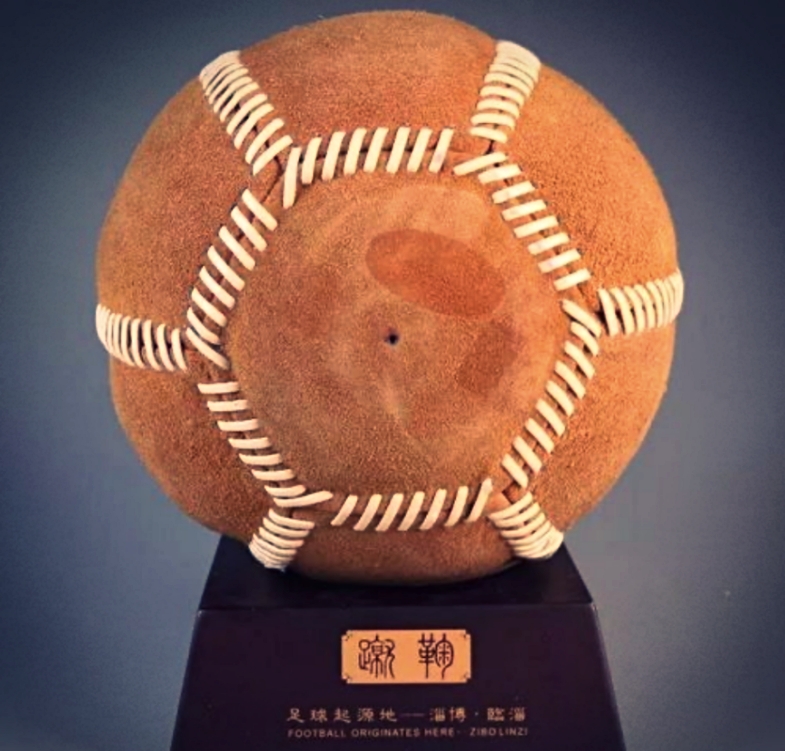

In 2004, FIFA identified China’s Linzi district in Zibo, Shandong province, as the “cradle of the earliest forms of football”. Therefore, the history of football dates back some 2,300 years. If we consider legends, it goes back even further. However, this does not mean that the Chinese invented football. After all, kicking a ball has a certain universality about it.

For example, in the Roman game of harpastum, each side would attempt to retain possession of a small ball for as long as possible. The Ancient Greeks competed in a similar game called episkyros. Both of these games were closer to rugby than modern-day football though. Perhaps people in Central America played the oldest ballgame. There the Mayans also enjoyed a game called pok-a-tok or pitz. They had a heavy rubber ball and a long, narrow pitch. In most cases, players used only their hips to pass the ball to each other.

In due course, being great chroniclers, the Chinese were probably one of the few ancient peoples who wrote about it. For example, Li You (ca. 55–135 CE), a Chinese poet, reminds us about justice and fair play:

The ball is round, the wall rectangular,

With six members each, the teams are balanced.

A referee is named and an assistant appointed.

Their interpretations of the rules must be constant.

With an honest heart and balanced thoughts,

No one can find fault with wrong decisions.

If football is regulated correctly like this,

How much this must mean for daily life.– Li You, Jucheng Ming or Inscription on the ball wall, the 1st or 2nd century CE.

In ancient China, football or soccer was known as cuju (pronounced as tsu-chu) which means to “kick the ball”. Originally it was part of military training during the Warring States period (475–221 BCE). Later, in the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), the popularity of the game spread from the army to the royal court and upper classes, who enjoyed playing cuju. Therefore, throughout the centuries, artists were depicting this game. For example, Huang Shen (1687–1772), a Chinese artist, painted Emperor Taizu of Song (927–976) and his officials playing cuju.

Emperor Gaozu of Han (256–195 BCE), born Liu Bang, was a famous football promoter. Rising from a humble peasant background, he turned into a politician and strategist. When he became an emperor, Liu Bang invited his father to live in the imperial palace. However, his father became depressed as he missed his favorite game, cuju.

To cheer his father up, Liu Bang built a football city. The area had a length and breadth of 48 meters (about 157 feet) and six-goal posts at either end. Games were frequent features at court feasts or diplomatic events. Teams could vary in size between 12 to 16 players. There was also a belief that the ball symbolized dignity. Consequently, Han dynasty cuju rules did not allow players to touch the ball with their hands. Nevertheless, the game itself was less than dignified and played in a highly physical manner.

The Han dynasty ball was an irregular two-piece leather sphere tightly stuffed with feathers. It was heavy and solid. As a result, players found it hard to control the ball. As a result, they could not kick the ball very high. This posed a limitation on improving one’s football skills and techniques.

In the Tang dynasty (618–907), the ball underwent a radical and complex change. The Chinese discarded the feathers and crude leather skins. They pioneered a new ball by inflating an animal bladder which they encased with pieces of leather. This produced a lighter, more spherical ball that was easier to play with. Football players could now refine their kicking and ball-passing techniques. Therefore the body contact between players became less aggressive.

The Chinese further developed the game in the Song dynasty (960–1279). Although football resembled volleyball at that time, players used their feet and not their hands. The ball was not permitted to touch the ground. Players had to send the ball back and forth accurately through a relatively small opening on the central net structure. It was not an easy task to accomplish. Here, a Chinese artist, Qian Xuan (1235–1305), painted Emperor Taizu of Song (927–976) playing cuju with his Prime Minister, Zhao Pu, and other court officials.

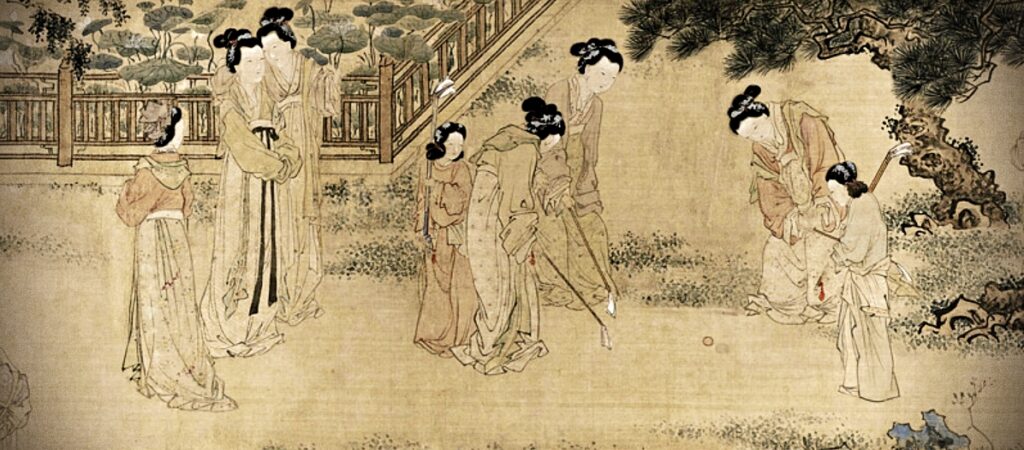

The lighter ball and change in the nature of the game led to the formation of the first women’s football team in around 900 CE. Coached by a senior lady of the court, this was a team like no other. Their game was more of a performance of dexterity. The team tried to pass the ball for the longest period of time and in the most entertaining way. Their coordination and teamwork were outstanding though. Once a seventeen-year-old girl outplayed and outscored an entire team of soldiers!

Du Jin (ca. 1465–1509), a Chinese painter, depicted one such group of court ladies engrossed in the game of cuju. Even their multi-layered dresses could not prevent the ladies from elegantly passing the ball to each other. His style and attention to detail had a profound influence on the late Ming dynasty (1368–1644) figure painting.

Nevertheless, things changed for women in the 10th century. The emperor had a personal preference for ladies with small feet. Consequently, ten-year-old girls had their feet tightly bound to prevent their growth beyond ten centimeters (4 inches). For the next nine centuries, this was regarded as a hallmark of female beauty in China. This practice put an end to court ladies being seen on football fields.

For male players, little had changed except for the quality of the football. By the 11th century, craftsmen had found a way to produce almost perfectly spherical footballs. The Chinese standardized the ball’s size and weight as well. Thus it began to resemble a modern ball and appeared three hundred years before any similar British design.

This standardization meant that football could reach almost everyone. Even children enjoyed playing cuju. Su Hanchen (1094–1172), a Song dynasty Chinese painter, knew that children at play are in a state of natural ease. For example, he depicted four children kicking a colorful ball. The artist captured many other interesting moments of child’s play, reflecting the richness of life. As a result, Su Hanchen became famous for his “baby play” paintings.

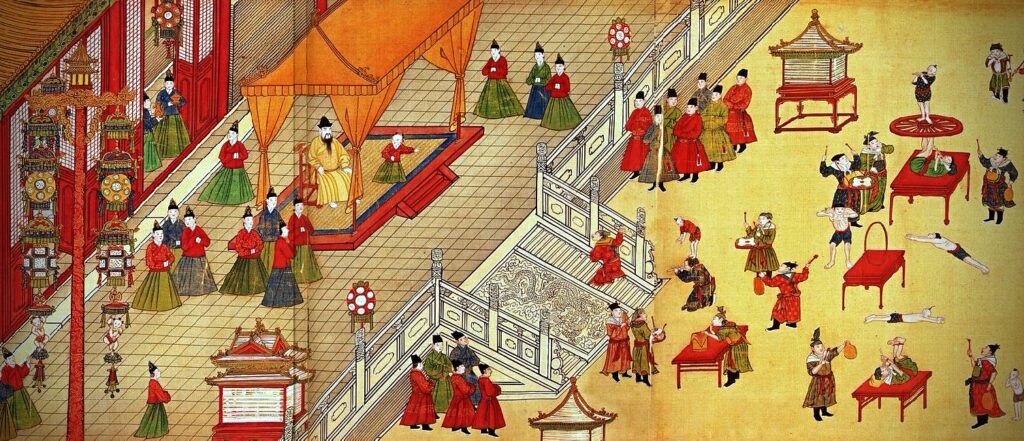

In the meantime, innovations in the visual arts helped to reveal the life of the imperial court. A new genre of paintings emerged depicting Emperor Xuande of Ming (1399–1435) at leisure. For example, Shang Xi, a 15th-century painter, showed the “Son of Heaven” playing various sports and watching his eunuchs playing games such as cuju. The emperor could appreciate the scroll Amusements in the Xuande Emperor’s Palace as he was also an accomplished artist.

Golf was another sport that the Chinese have played since ancient times. The game was known as chuiwan or hitting a small ball. It had distinct similarities to modern-day golf. For example, the Chinese drove a ball with a club into holes in the ground. The holes, marked by colored flags, were of varying difficulty.

Initially, only wealthy people could afford to play chuiwan. In the Liao (916–1125) and Jin dynasties (1115–1234) it became the favorite pastime among the general public. They liked to play it on the Hanshi or Cold Food Festival. This included a tradition of avoiding lighting any kind of fire, even for the cooking of food.

One of the most avid chuiwan players was Emperor Huizong of Song (1082–1135). Artisans made imperial clubs of the most precious materials like gold, decorated with precious stones. Apart from playing golf, the emperor also enjoyed painting. He created a number of Chinese traditional paintings, the most famous of which is Auspicious Cranes.

By the middle of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), we do not find any more references to chuiwan. When golf was introduced into China people thought of it as a foreign game. They could not see any similarities with chuiwan. Nevertheless, Chinese records of this game predate any Western accounts. Therefore, it could have traveled west in the wake of the golden hordes of Genghis Khan (1162–1227), the emperor of the Mongols. It is possible that his soldiers introduced golf to the West.

Similarly to the Mongols, the Chinese were ardent horse riders. Horses were vital to an empire that had to constantly defend itself from nomadic invaders. Therefore, the Chinese innovated the stirrup, the saddle, and the horse collar. In the Tang dynasty (618–907) they promoted a novel game, polo, or the “sport of kings”.

One of the most passionate devotees of polo was Li Longji (685–762), later known as Emperor Xuanzong of Tang. In 709, the Tibetans sent envoys to the Tang capital to escort a princess for an arranged marriage. They were largely nomadic and highly versatile horsemen. The Tibetan word for a ball is “pulu”, which refers to the willow used to stuff it. Before departing, the Chinese emperor’s team invited the Tibetans to play a polo match.

The aggressive nomads soundly defeated the Chinese, resulting in a loss of face for the current emperor. Li Longji decided to take avenge with only three men on his side. Despite being outnumbered, the Chinese triumphed over the Tibetans. However, the princess was not returned and was sent away to Tibet. When Li Longji took the throne, he encouraged his officials to sharpen their battlefield performance by using polo as a training exercise.

Before the Song dynasty (960–1279) most sports had a direct connection with military training. However, as the country became more affluent, Chinese sports evolved to become an integral part of everyday life. Often street-side stages were built for crowd-pleasing acrobatic shows. Sporting culture thus became a daily part of the community and ball games, gymnastics, and martial arts could be found everywhere.

Their nature had changed though, and the competitive aspect of the sport was no longer prevalent. Still, the Chinese continued to push their bodies to the limit. Performers would do anything to draw the crowds, showing off incredible feats of strength and skill. The gymnastic accomplishments in which Chinese athletes excel today have their origins in these street performances.

Throughout the centuries China incorporated philosophical and moral qualities into their sports. The physical culture of ancient China had a many-sided influence on the emergence of modern sports. With their unique national features, ancient sports form an intrinsic part of Chinese civilization. The vast empire that innovated its very own sports traditions is now aiming to lead the world once again. With victory in its sights, the dragon is waiting to be awakened.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!