5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

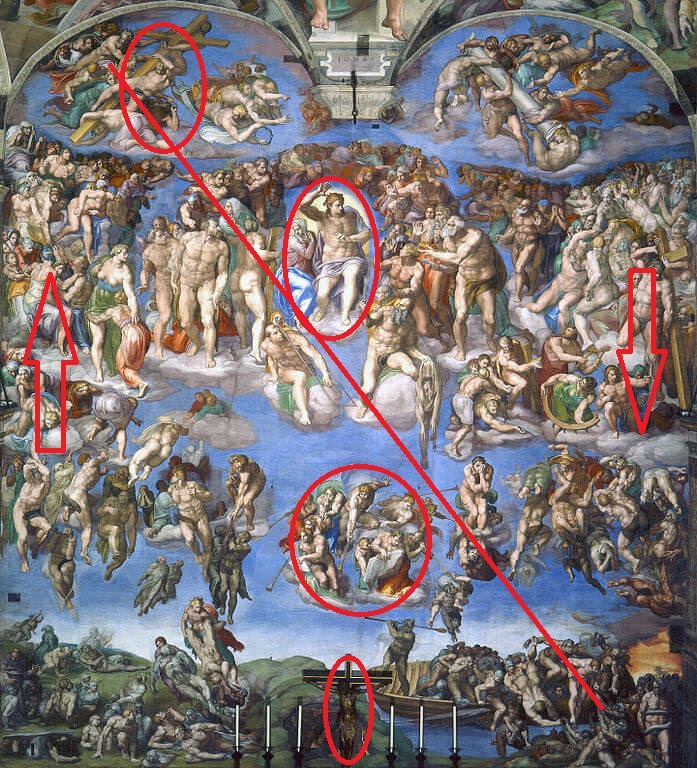

There is a lot happening in this Sistine Chapel altar-wall fresco. Narratives within other narratives that contain enough imagery to last scholars a good while. With so much information and facts to bog you down in Michelangelo’s The Last Judgement, how do we make heads or tails of such a dynamic and intriguing piece of work? Part of interpreting and understanding Michelangelo’s masterpiece lies in the history surrounding the Catholic Church in the 16th century.

Roughly 25 years prior to his completion of The Last Judgement, Michelangelo (1475-1564) completed the ceiling frescoes (1508-1512) of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican City.

The narrative style content span a size of 133 x 46 feet; no small feat for a man who was a master sculptor and not a painter. Old Testament stories fill the ceiling, ranging from prophets, ancestors of Christ, and the story of Israel’s salvation.

According to Giorgio Vasari, Pope Julius II approached Michelangelo to paint the ceiling out of mere artistic instigation from other Italian artists. These artists desired to see Michelangelo, already an established sculptor, fall flat on his face or tire of the project and the Pope, departing Italy altogether. For being primarily a sculptor, the master completed one of the art world’s most well-known masterpieces.

Not long after the completion of these frescoes, in 1517, the Protestant Reformation took form under the leadership of Martin Luther in Northern Europe. The Last Judgement was Pope Paul III’s response to uncertainty within the Catholic Church. Meant to be ‘scary,’ the narrative was overwhelming to anyone viewing it: a reminder of Christ’s pending return and that followers of the Church would have to answer for their sins.

The Last Judgement is located in the altar room where the Pope would lead mass. And historically the College of Cardinals elected the new Pope in this area. This was the intended audience for the painting: a very select group of people who would understand the heavy religious themes.

It is an epic painting with such dense force and psychological meaning; a total 180 from the approach with the ceiling frescoes.

Figures are moving up, lifted by angels; damned souls are pulled down by demons and pushed by angels. Christ’s own narrative features three times in one continuous piece. He hangs on the cross in the bottom center; He ascends to Heaven in the top left corner; He descends from Heaven in the middle of the painting, which is the direct focus on the altar wall. Furthermore, there is a clear line from the scenes of Heaven and Hell, an invisible diagonal gesture. There is chaos and order all in one extensive scene.

The dynamic movement, larger than life scale, and overall meaning of the fresco come together to form one of the most well-known Renaissance paintings to have existed. In the words of Giorgio Vasari:

“[H]e…threw it open to view in the year of 1541, I believe on Christmas day, to the marvel of all of Rome, nay, of the whole world; and I, who was that year in Venice, and went to Rome to see it, was struck dumb by its beauty.”

– Giorgio Vasari, in The Lives of The Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, pp. 390-91.

Self-portraits in major artworks are not an unusual thing. However, what intrigues art historians, and viewers alike, is Michelangelo’s depiction of himself in the flayed skin of St. Bartholomew. It carries a sense of tragedy and horror, at the same time. And ultimately makes the viewer wonder what the state of Michelangelo’s mind was in during the years leading up to the completion of this work of art.

Though the proportions of the figures are off-balance and rather dense, the nudity was what upset the Church. But according to Vasari, trouble started before Michelangelo even finished the fresco:

“When Michelangelo had completed about three quarters of the work, Pope Paul went to see it, and Messer Biagio da Cesena, the master of the ceremonies, was with him, and when he was asked what he thought of it, he answered that he thought it not right to have so many naked figures in the Pope’s chapel. This displeased Michelangelo, and to revenge himself, as soon as he was departed, he painted him in the character of Minos with a great serpent twisted round his legs. Nor did Messer Biagio’s entreaties either to the Pope or to Michelangelo himself, avail to persuade him to take it away.”

– Giorgio Vasari, in The Lives of The Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, pp. 387.

Around the time of the artist’s death, the Pope commissioned Daniele da Volterra to go behind Michelangelo’s work and cover the nude figures with paintings of cloth.

Giorgio Vasari. The Lives of The Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Trans. Gaston du C. de Vere, Ed.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!