Hanuman: The Revered Monkey God in Hindu Mythology

The revered monkey god Hanuman is one of the most iconic in Hindu mythology. He embodies unparalleled strength, unwavering devotion, and boundless...

Maya M. Tola 19 September 2024

13 May 2024 min Read

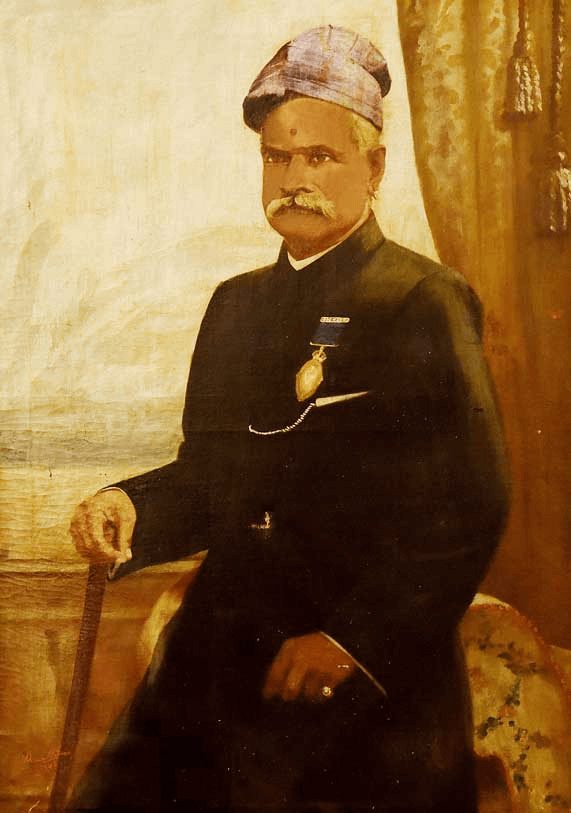

Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906) was one of the most celebrated and prominent artists from India. His works combined European realism with Indian sensibility. For his paintings, Varma took inspiration from diverse sources like the chanting of Vedic verses, the Kathakali dance dramas, and the artistic interpretations of Sanskrit epics namely, Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Varma also printed affordable oleographs of his paintings, making his artworks accessible to the Indian public. Varma won many awards for his paintings and in 2013 a crater on Mercury was named after him!

Varma was born into an aristocratic family at Kilimanoor Palace in the former princely state of Travancore, present-day Kerala, India. His father was a scholar of Sanskrit and Ayurveda. His mother was a poet and writer who composed music for Kathakali dance dramas. The Kingdom of Travancore was a matrilineal society in which family lineage was traced through the female members. Even though the property was controlled by the eldest male member, only the female descendants could inherit it.

A young Varma was patronized by Ayilyam Thirunal, the Maharaja of Travancore. Thereafter, he began his formal training as a painter. He learned the basics of painting in the city of Madurai, watercolor painting from Rama Swami Naidu, and oil painting from Dutch portraitist Theodor Jenson. Although Varma was recognized as a good artist, his career really flourished after Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad of Baroda became his main patron. Varma painted portraits of Indian royals, British officials, and Hindu gods and goddesses.

The figures in the Stolen Interview or Hesitation are probably lovers. The rules of courtship are quite evident here: the man is anxiously gazing at his beloved while the woman is acting demure and coy. She is nervously plucking at the rose that the man has given her. Varma frequently painted flowers in his paintings as ornaments worn by women or for their symbolic meanings. Here the rose represents love and romance.

The woman is dressed simply but elegantly. Her gold-bordered sari and pearl jewelry suggest she belongs to an affluent family. The source of the light is outside the painting but illuminating the two figures. It seems the spectators are witnessing a private moment where they are complete outsiders.

Rani Bharani Thirunal Lakshmi Bayi was the Senior Queen of Travancore from 1857 until her death in 1901. Rani Lakshmi Bayi of Travancore is a fine example of Varma’s dedication to painting fine details on costumes and jewelry. The Queen is dressed in an opulent gold skirt with silver details. A heavily gold-bordered red fabric drapes her upper body which contrasts with her royal blue blouse.

She is wearing an oddiyanam, or a waist ornament. The purpose of the waist belt was not just to hold the sari, it actually was to keep the waistline slim. The tight belt accentuates the hips of the woman, which in southern India is a sign of feminine beauty. She is wearing pearls and traditional jewelry of the Malabar region. On her fingers, she wears rings studded with precious gems. The use of gold shows Varma’s admiration of the Tanjore paintings combined with European realism.

It is not surprising that Varma chose to paint female figures; in the matrilineal society of the Travancore Royal family, he was surrounded by talented and powerful women. Moreover, in Indian culture, women’s clothes and jewelry are symbols of their family’s social status. Red and gold are colors associated with married women, who had some social status in Indian society. Two books are seen in the painting: The Young Lady’s Book and Near Home, or, The Countries of Europe Described. It is not known if the Queen could read English but she received a good education.

The identity of the woman in Portrait of a Lady is unknown but she is a Maharashtrian woman of high class. Her jewelry, especially her elaborate nose-ring or “nath”, is made of a cluster of pearls and rubies. It is also a symbol of her marital status. Her black sari with gold polka dots and the gold border is casually draped over her shoulder. Even today Hindu married women avoid wearing black because it is the color of bad luck. However, different parts of India have different cultural traditions and that is one beautiful sari!

For There Comes Papa, the models were Varma’s daughter, Mahaprabha Thampuratti of Mavelikkara, and her son, Marthanda Varma. In this double portrait, Mahaprabha is wearing a traditional sari of southern India. This was the traditional form of wearing a sari without a blouse. It is argued that the custom of covering the upper body was introduced by the British colonials in pre-independent India. Their Victorian morality of covering all body parts clashed with the Indian sari which permits some amount of bare skin. The little boy only wears jewelry, not clothes. This painting celebrates motherhood and the comforts of family life. There is a dog at the woman’s foot and the interiors are painted in fine detail.

Jatayu Vadham (The Killing of Jatayu) captures a very moving episode from the Sanskrit epic Ramayana. Ravana, the demon god of Lanka, is abducting Sita, the wife of Rama. Jatayu was the divine bird who sacrificed his life trying to save Sita from Ravana. His last rites were performed by Rama, an avatar of the god Vishnu.

The painting shows Ravana chopping off one of Jatau’s wings with his sword. Varma captures the strength of Ravana who is smiling at his evil victory. Sita is portrayed as a helpless woman, unable to witness the killing of Jatayu. Varma created another version of this painting in 1906 which is displayed at The Jaganmohan Palace, Mysore. There are some differences between the two paintings but the Ravana here is perfectly evil!

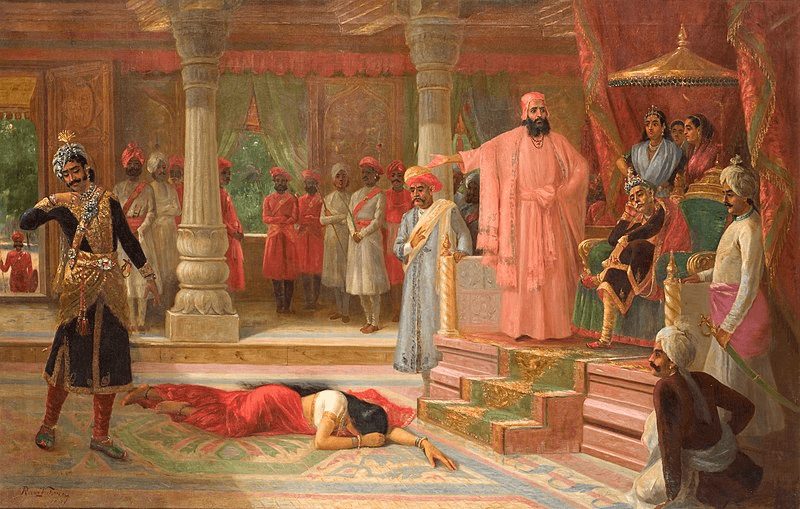

Droupathi in Virata’s Palace depicts the scene of Draupadi’s humiliation from the epic Mahabharata. The scene is from the Book of Virata, the fourth book of Mahabharata. It discusses the 13th and final year of the Pandava’s exile incognito. The five brothers, Yudhishthira, Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula, and Sahadeva, along with their wife Draupadi decided to spend the year in the court of Virata. They assumed different identities and Draupadi became Malini, the Sairandhri, or hairdresser of a queen. Kichaka, a commander in Virata’s army is attracted to Draupadi and molests her. Despite Draupadi’s rejection and warnings that she is a married woman, Kichaka continues to pursue her.

In Droupathi in Virata’s Palace, Varma captures the moment when chased by Kichaka, Draupadi enters the court of Virata seeking justice. Her husband Yudhishthira is standing in disguise in the court, unable to protect his wife. Draupadi is lying face down, humiliated, and shamed. Kichaka is unapologetic and proud because according to him she is a servant of the queen. This was the second time Draupadi was humiliated and sexually assaulted in court in front of her husband. Unable to bear the humiliation, she demanded Bhima kill Kichaka for justice.

Varma’s painting has more than 20 figures, each one of them accommodated with no compromise of light and space between them. Varma captures the emotion of shock and helplessness in each figure with the utmost care. This episode from the Mahabharata is often dramatized in Kathakali dance performances.

Damayanti and the Hamsa portrays a popular love story from the Vana Parva of Mahabharata, between Princess Damayanti and King Nala. Damayanti and Nala are also the central characters of Nishadha Charita compiled by Sriharsha, one of the five great epics of Sanskrit literature.

The Hamsa or the swan tells Damayanti about Nala, and she falls in love with him. The swan is actually a messenger sent by Nala. The two are eventually married and go on to have a difficult but happy life together. Damayanti was celebrated for her beauty and chastity. Varma used his imagination to paint a beautiful woman, dressed elegantly in a red sari. The setting is very idealized and romantic with marble interiors and a lotus pond.

For Damayanti’s sari, Varma took inspiration from the fashionable women of Bombay where he spent many years. Unlike Kerala, where the sari was tightly wrapped around the body, the Bombay women wore it differently with interesting drapes and graceful folds which Varma found quite appealing.

In Goddess Saraswathi, Varma is playing with the iconography of the Hindu goddess Saraswati. She is the goddess of knowledge, music, and the arts. Along with Lakshmi and Parvati, Saraswati forms the trinity of Hindu goddesses. In traditional iconography, Saraswati is depicted as a beautiful woman dressed in a white sari, sitting on a lotus, and playing the veena. White symbolizes purity and wisdom. Generally, she is shown with four hands holding a rosary, a book, a quill, and the veena. Sometimes, there is a swan and peacock near her. The swan is a symbol of transcendence and the peacock of the splendor of color and dance. She is often sitting near a body of water, alluding to her past as a river goddess.

Varma retained the iconography of the goddess Saraswati with the addition of the crown which is often seen in Tanjore paintings. The flowers scattered around are Chrysanthemums, frangipani, and hibiscus. With her perfect facial features and graceful white sari, Varma’s Saraswati is divinely human.

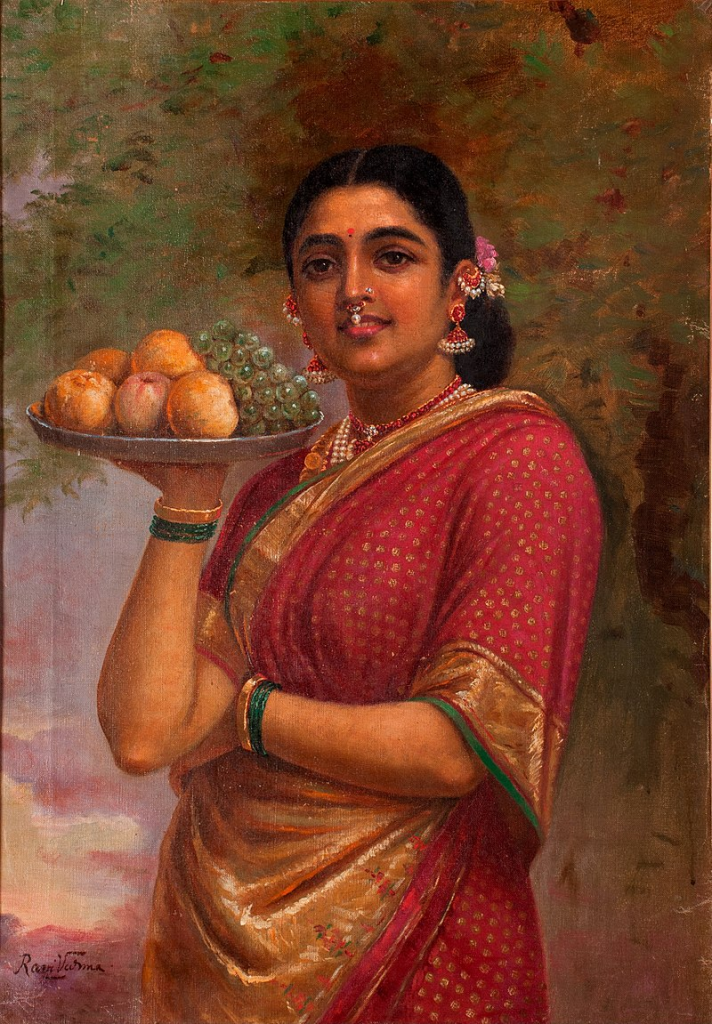

Verma traveled the length and breadth of India for his subjects. The Maharashtrian Lady is a portrait of an anonymous woman. Varma preferred painting women with big, bold eyes, a symbol of feminine beauty in Indian culture. The woman is holding a plate of fruit, which shows Varma’s European influence on still-life paintings. Fruit represents fertility combined with the sensuality of the female subject. Her gaze is direct and fixed on the spectator suggesting self-confidence. Verma was skilled in using oil colors for painting Indian skin tones and the vibrant colors of the women’s silk saris.

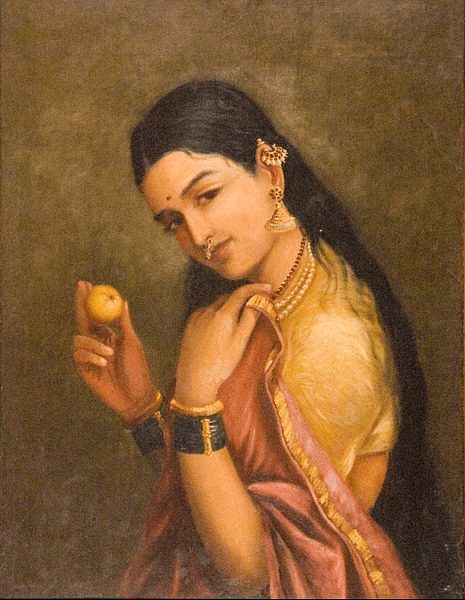

In Woman Holding a Fruit, Varma portrays a young woman. Her gaze is direct and playful. Her long hair is open which symbolizes female sexuality in southern India. Also, her sari is falling from her shoulders suggesting she is both innocent and aware of her sensuality.

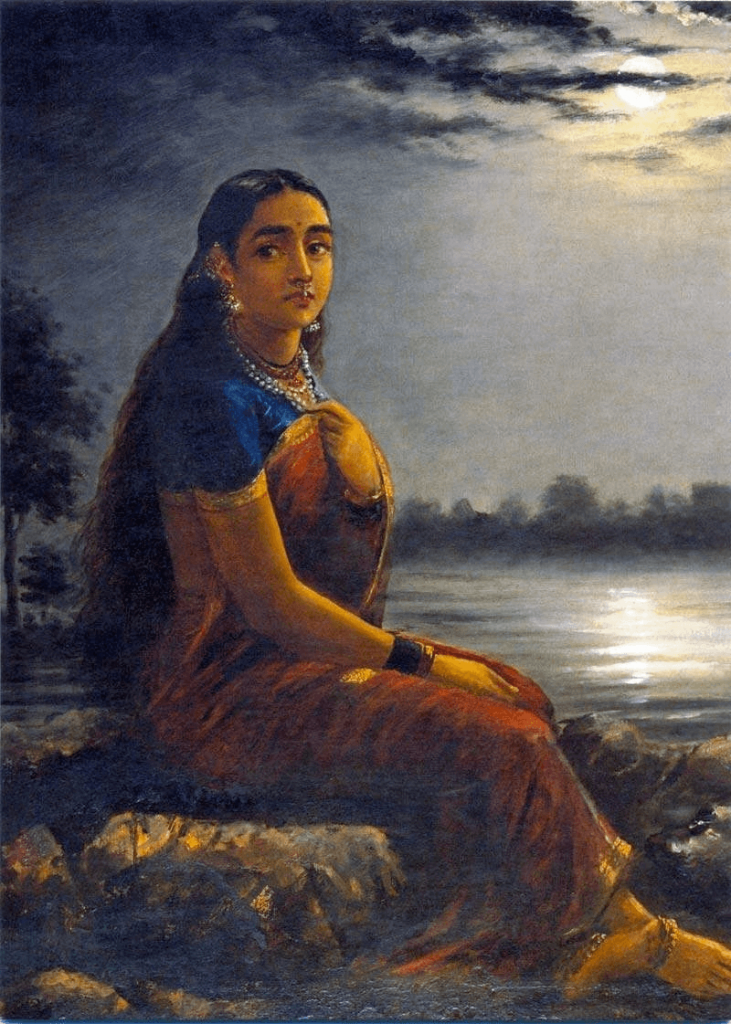

For Lady in the Moon Light, the model was Anjanibai Malpekar (1883-1974). She was a talented Indian classical singer and also the first woman to be awarded a national fellowship by Sangeet Natak Akademi in 1958. She was the muse of three other paintings by Varma entitled, Lady with Swarbat (1874), Mohini (1894), and Heartbroken.

This painting depicts a woman sitting near a lake or river under a full moonlit night. She is looking at the spectator who seems to have disturbed her solitude. She is dressed beautifully yet modestly compared to Varma’s other female subjects. The full moon is synonymous with feminine beauty in popular Indian culture. Varma uses this romanticized setting to portray his muse who was already a talented singer.

The Galaxy of Musicians portrays a group of female singers with traditional musical instruments. The women wear traditional Indian costumes from different regions. The painting was commissioned by the Maharaja of Mysore. There is a Muslim woman on the right and a Nair woman playing the veena on the left. In the second row, there is also an Anglo-Indian woman with her fashionable hat.

Verma also used the artistic technique of chiaroscuro with strong contrasts between light and dark areas. Though a Western technique, Varma was the earliest Indian artist to use it in his paintings. The effect of Chiaroscuro gives Galaxy of Musicians a dramatic feel in which each figure is given an individual expression.

Through this painting, Varma gives us a glimpse into the diversity of the Indian cultural landscape. However, the painting leaves out women from lower castes, classes, and tribal groups. In the late 19th century, national unity was a new concept in India, but the painting was one of the early attempts to envision this alien concept.

Colored lithographic prints or oleographs are the printed versions of Varma’s original paintings. Before Varma’s press, in India, oleography was used for gaudy ‘calendar arts’ and commodity packaging. The idea of printing and distributing oleographs were given to Varma by Sir T. Madhava Rao, former Dewan of Travancore, and later Baroda. The Ravi Varma Fine Arts Lithographic Press started in 1894 in Bombay.

Each of Varma’s paintings comprised 7 to 30 lithographs. Varma’s oleographs made the Hindu gods, goddesses, and epics accessible to the common Indian public. The gods and goddesses who only lived in temples or palaces of the royal families thus found their way into the homes of ordinary Indians through oleographs.

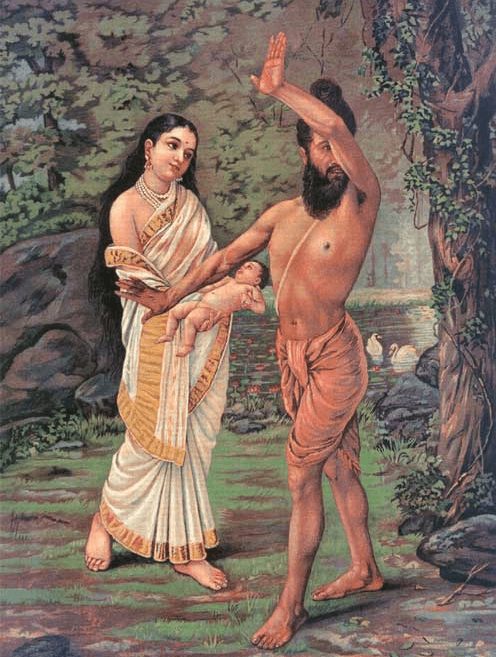

The Birth of Shakuntala was the first oleograph from Varma’s Press. Here Vishwamitra is seen rejecting Menaka and his daughter Shakuntala. Knowing that the gods had tricked him into marrying Menaka, he renounced the world. The love story of Shakuntala and King Dushyanta is recited in the Mahabharata and adapted into Sanskrit drama by Kalidasa in Abhijñānaśākuntala (The Sign of Shakuntala). She was the mother of King Bharata, who gave India its Sanskrit name- Bharat. The influence of Kathakali dance drama is evident in the eye expressions and the exaggerated hand movements of Vishwamitra.

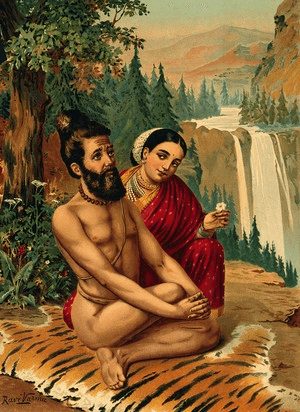

Menaka The Nymph Tempting The Yogi, Viswāmitra depicts the story of a beautiful celestial woman and a sage. Vishwamitra was a dedicated and most revered sage who challenged the power of the gods. Indra, the king of gods sent Menaka to seduce Vishwamitra, who was meditating. Menaka succeeded in seducing Vishwamitra with her beauty. She fell in love with him and they had a child named Shakuntala. Here, Menaka and Vishwamitra are seen in a picturesque setting. While Menaka is looking seductively at Vishwamitra, he appears confused and avoids her gaze.

The model for Mohini was Anjanibai Malpekar, another renowned Indian classical singer. Mohini was a Hindu goddess, the only female avatar of Vishnu. In popular lore, she is portrayed as an enchantress, a femme fatale who destroys her lovers. Varma captures Mohini’s seductive and carefree nature by painting her in a sheer white sari, with bare arms, and her hair loose.

In Hinduism, Lakshmi is the wife of Vishnu. Along with Saraswati and Parvati, she forms the Tridevi, or holy trinity of goddesses. Her name suggests the one who leads to goals. For mankind, eight types of goals are necessary: spiritual enlightenment, food, knowledge, resources, progeny, abundance, patience, and success. The iconography of the goddess Lakshmi is an elegantly dressed woman, showering gold coins which signifies the importance of the economic activity to sustain life. She uses an owl as her vehicle, sits or stands on a lotus flower, and holds lotus flowers in her hands. She typically has four hands which represent dharma (duty), kāma (desire), artha (meaning), and moksha (liberation). Also, her depictions often have two elephants in the background symbolizing work, activity, and strength.

In Goddess Lakshmi, Varma retains most of the iconography of the goddess Lakshmi with slight modifications. The gold coins are missing, there is only one elephant in the background, and she is wearing a crown which is seen in Tanjore paintings. For Goddess Saraswati and Goddess Lakshmi, Varma’s model was a Goan lady called Rajibai Moolgavkar. Although Varma used female models to paint goddesses, he idealized their faces to take away any resemblance.

Vishnu is one of the important deities of the Hindu Pantheon. Along with Brahma, the creator, and Shiva, the destructor, Vishnu is considered the preserver of the universe. Rama and Krishna are the avatars of Vishnu who destroy the evil forces on earth and set the balance between good and evil.

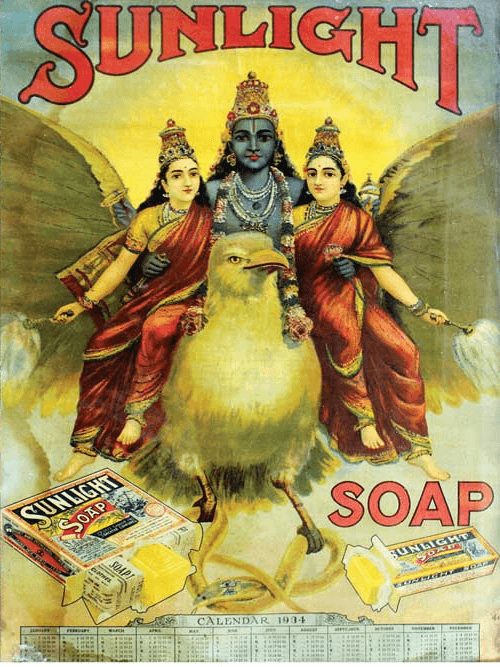

The Vishnu Garuda Vahan oleograph is seen here on a calendar from 1934 printed by a soap company. Vishnu is sitting on Garuda, the mythical eagle-like bird. Vishnu’s iconography shows him as a blue-skinned man with four arms holding his favorite weapons. In Vishnu Garuda Vahan, Vishnu is sitting on Garuda with his two wives: Shri Devi and Bhu Devi, who are actually two forms of Lakshmi. This image of Vishnu with his two wives is rarely seen in popular representations.

In 1903, Varma sold his press to Fritz Schleicher, a German who retained the copyrights for the prints. He was an enterprising man and used the oleographs for advertisements, calendars, postcards, playing cards, and matchbox covers. The press remained in business until 1973 and eventually closed down completely in 1980.

Though the oleographs of Hindu gods and goddesses were reduced to advertisements and calendar art, they must have found their way into ordinary Indian homes, and that was most important for Varma.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!