Jean-Étienne Liotard Breakfast Scenes

The 18th-century painter, miniaturist, and pastelist Jean-Étienne Liotard is perhaps one of the most eccentric artists of his time. Known for his...

Anna Ingram 16 September 2024

5 March 2023 min Read

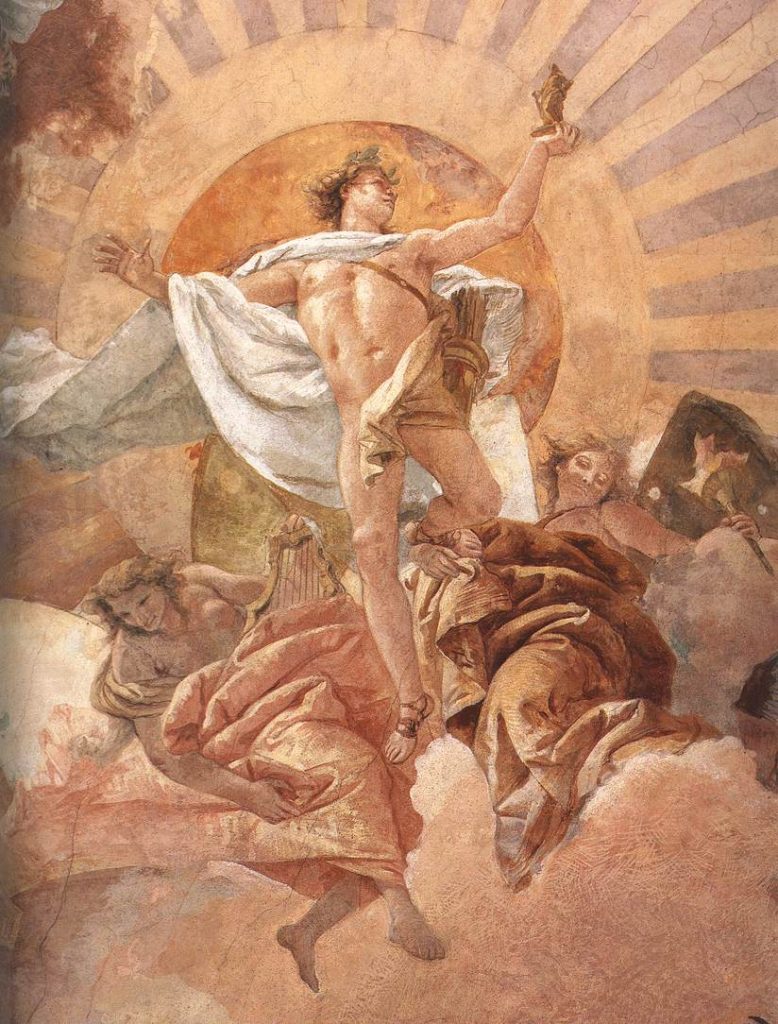

Giambattista Tiepolo brought Venice back to the artistic spotlight in the 18th century. Without a doubt, the crowning achievement of Tiepolo’s career are the frescoes in Würzburger Residenz, a palace in Bavaria, in southern Germany. This is the largest ceiling fresco in the world, decorating the vaulting of the grand staircase of the palace, leading from the ground floor to the first floor. It measures 190 x 30.5 meters!

The age of Rococo is strongly associated with the works of French artists like Antoine Watteau, Francois Boucher, or Jean-Honore Fragonard. However, Tiepolo’s romantic pastel colors in an otherwise dramatic scene helped define the characteristics of Rococo painting.

Tiepolo and his assistant, his own son Domenico, lived and worked in Germany from 1750 to 1753, commissioned by Prince Bishop Karl Philip von Greiffenklau.

The enormous fresco shows an allegorical scene, Apollo and the Four Continents. Today, we distinguish more continents, but back in the 18th century Oceania and Antarctica were, for example, not yet very well known.

The basic principle of the fresco is quite simple. It presents the passing of the sun around the world. In the center, we have Apollo, the sun rising behind him. Beside him are two women holding his symbols, a lyre and a torch. Two cherubs prepare his chariot. Scattered in the sky, we see allegorical figures representing the planets. For example, in the dark cloud below Apollo, we see Venus and Mars. There is also Mercury, Jupiter, and Saturn, as well as Diana, representing the moon.

However, the most impressive part of the fresco lies circumferential to the walls, where we see the personifications of the four Continents. As we begin to ascend the staircase, first we see America. She is a native American woman, dressed in traditional attire. She sits upon a huge alligator. In this composition, America, the New World, symbolizes everything that is still savage.

To the right of the personification of America, a few native inhabitants are preparing food outside the home, a clear sign of primitiveness for the then-noble Europeans. At the time, there were rumors that Americans were cannibals as well, so Tiepolo added some human heads. You can see them next to a scared European man, rendered with impressive foreshortening, watching the Natives. The New World, fairly new at the time, was full of all kinds of outlandish rumors. Here, America and the other Continents are presented through the eyes of Western Europeans of the time, a time when imperialism was the word of the day and concepts like postcolonial theory were still unknown.

Moving up the stairs, we come across Asia and Africa. Africa is shown as a center of commerce. It is presented as a black woman wearing a turban, bringing together the traditions of Sub-Saharan and North Africa, according to Europeans of the time. Africa is sitting upon a camel in the center of a bustling marketplace. Meanwhile, a merchant offers her incense and textiles, symbols of the wealth of the continent.

Near them, a monkey plays with the ostrich, an example of the exotic animals that make their home in Africa.

On the other side, the personification of Asia is perched upon an elephant. The figures around her mark the continent as the cradle of the written word, science, and monarchy. Close to the feet of the elephant, we see a chained prisoner, showing the strategic importance of Asia.

To her right, some figures sit around an obelisk. The figure with the yellow tunic is the allegory of the monarchy. Another holds a caduceus, perhaps representing medicine. The writing on the wall is a purely made-up ornamental language.

Reaching the end of the staircase, we find the culmination of the composition: Europe. Europe sits on a throne, resting her hand on a white bull, reminding us of her origins. Around her, we see allegorical figures of the arts, among them the painter himself and the architect of the building.

Above Europe, there is a medal showing the proud commissioner of the fresco, Carl Philipp von Greiffenclau.

The Würzburger Residenz fresco is definitely one of the greatest masterpieces from the Rococo epoche. It is also a very important witness of its times, showing the very narrow, self-centered worldview of 18th-century Western Europeans. I believe we can still enjoy the Tiepolo’s craft and talent, as long as we remember its historical context.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!