Masterpiece Story: The Phoenix Portrait of Elizabeth I

One of the most famous depictions of Elizabeth I is Nicholas Hilliard’s Phoenix Portrait, depicting the Queen with a pendant shaped like a mythical...

Guest Profile 5 December 2024

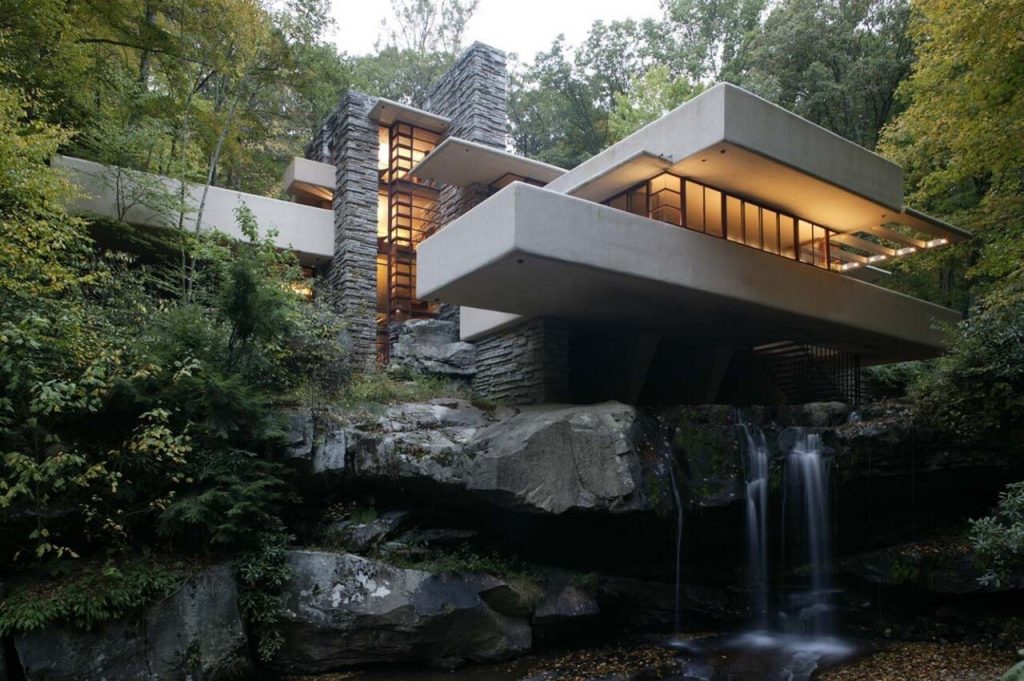

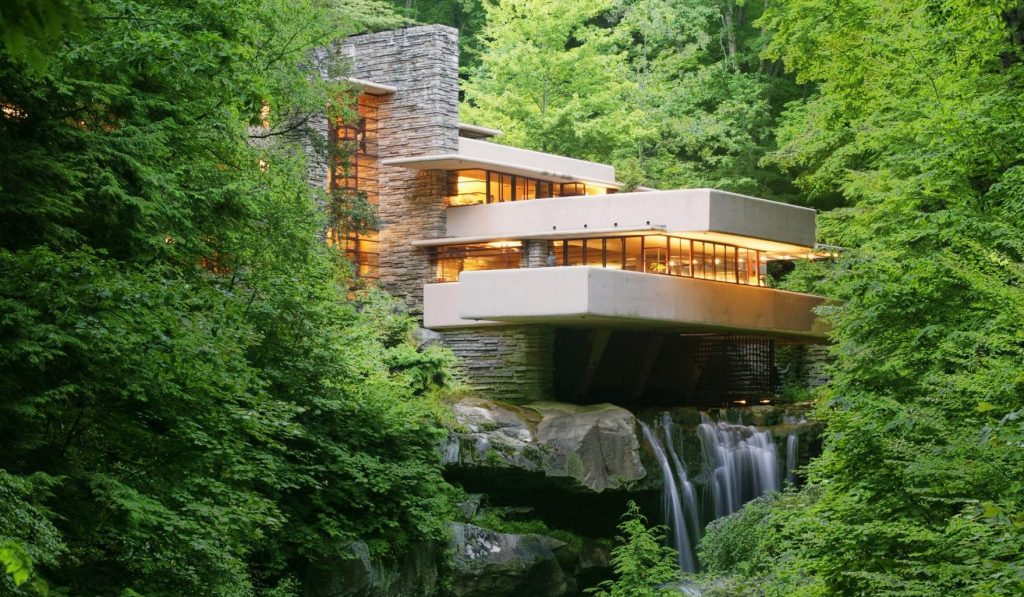

There are many iconic buildings, and it feels like more and more are being called that by the hour. But the list is a lot shorter if we only consider private houses perceived as iconic by the public. Fallingwater certainly belongs in that group. Together with other modernist villas such as Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier, Glass House by Philip Johnson, or Farnsworth House by Mies van der Rohe. Fallingwater’s troubled history and Wright’s controversial and well-publicized private life and prolific oeuvre are a perfect mix of bringing architecture into a broader awareness.

Wright’s career was not only long at over 70 years but also remarkably prolific. He designed around 800 buildings and saw the construction of over 300 of them. In other words, more than ten buildings per year, or almost one per month. A staggering number, even if we factor in the foundation of Taliesin Fellowship, which he didn’t work alone.

Frank Lloyd Wright grew up at a farm, always in the vicinity of nature and in tune with its natural rhythm. He began his career in 1887 in Chicago, quickly joining the firm Adler & Sullivan. There he had a chance to work for the famous Louis Sullivan, also known as the “father of skyscrapers”. Sullivan had a persuasive impact on young Wright and his ideas.

Quickly, Wright developed and perfected his signature Prairie Style. Its ideals are grounded in the closeness to nature, with a focus on the organic merging of the house and the surrounding environment. This resulted in a series of Prairie Houses. Their style was characterized by an open floor plan, the use of local materials, and horizontal lines. These features made the houses more aligned with the surroundings. All those traits are still visible in Fallingwater, even though it was built several decades later, and it would be questionable to call it a Prairie House due to its location.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Wright’s private life affected his work. An affair with the client, Mamah Borthwick Cheney, resulted in a well-publicized separation from his wife. So he left the United States, with Mamah Borthwick, for Europe. When he came back in 1911, he bought a plot of land on which his ancestors lived in Wisconsin. This is where he built the legendary Taliesin.

Bad luck plagued Taliesin. Starting with the fire and murders in 1914, where Borthwick was among the seven victims of a servant. There was a subsequent fire, then the Great Depression hit. All of this combined caused a certain level of stagnation in Wright’s commissions. The recovery came only in 1932 when his new wife Olgivanna called for students to join Wright in Taliesin. This was the beginning of the Taliesin Fellowship, which later converted into The School of Architecture in Paradise Valley, Arizona.

The Fallingwater commission came at the perfect moment to revive Wright’s stalling career. At the same time, he already had experience, which benefited the project. It also allowed him to progress later when designing the Guggenheim Museum building in New York, yet another iconic achievement.

The man without whom Fallingwater would never come to existence. Clearly, he was a man of exquisite taste, for he also commissioned another house that is considered iconic: the Kaufmann Desert House in Palm Springs by Richard J. Neutra.

By trade, you could call Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr. a businessman. He was an owner of the Kaufmann Department Store in Pittsburgh, which he inherited and throughout the years successfully developed. But he also devoted a lot of his time to public works. Kaufmann was the driving force behind the creation of the Research Bureau for Retail Training in 1918.

His meeting with Wright came from two sources. After reading Wright’s An Autobiography, Edgar Kaufmann Jr. returned from Europe and joined the Taliesin Fellowship in 1934. Wright’s ideas resonated with the young man. He also discussed them multiple times with his parents. At the same time, Edgar Kaufmann Sr. was active in New Deal public works programs for Pittsburgh, where he became familiar with Wright’s proposals for these projects.

His own interest, combined with his son’s raving, resulted in a visit to Taliesin. An exchange of correspondence and ideas followed. The rest, as they say, is history.

Many rumors surround the design of Fallingwater. One claims that Wright designed the whole house in a few hours. The cause of this rush was from Kaufmann calling to inform him of an unscheduled visit to check the progress on the project (which, like any good procrastinator, Wright had not even touched). Even given Wright’s experience and the fact that Taliesin was chock full of his apprentices, this claim seems unrealistic.

However, another rumor may hold a little more truth in it. Kaufmann expected the house to be built opposite the waterfalls so that his family may enjoy their unobstructed view. So it came as a bit of surprise when Wright decided to sit the house smack-bang on top of it.

The house was designed in 1935, and construction was completed by 1939. In line with his “organic” take on architecture, where art is in union with nature, Wright designed the house from local materials. Whatever could be sourced at the property was, including the quarried sandstone.

With its cantilevered terraces, Fallingwater’s structure echoes the structure of the rocks in the Bear’s Run waterfall. All the terraces are anchored to the central stone chimney. This play of strong horizontal lines of the roofs serves to merge the house with its surroundings. It is a sizable house, but yet it doesn’t seem to tower over the waterfall, more leaning low over it. Interestingly, in the vein of blurring the lines between nature and art, the square footage of outdoor terraces of Fallingwater is almost the same as that of its indoor rooms.

The construction did not go without drama. There was a significant controversy between Wright and Kauffman and the engineers about the amount of reinforcement needed to support the daring cantilevers. When Kaufmann obtained an independent opinion, Wright threatened to withdraw from the project. The structural survey in the 1990s discovered that additional reinforcement had been added. It is not certain whether the contactor made the call or Kaufmann. Although, since Kaufmann had to fund the extra steel, it was probably with his blessing. However, even with reinforced concrete by 1995, the house was on the verge of collapse. It was caused by the still insufficient reinforcement, as well as the demanding climate conditions on-site. Emergency girders were introduced in 1997, and in 2002 the building was permanently repaired.

Wright, as may be expected by a perfectionist, also designed the interior of the house. Here again, he uses materials to blur the line between the interior and exterior. For example, the stone floors in the living room continue well outside on the terrace. The vast expanses of windows expose the interior to nature outside.

The color palette is limited, focused primarily on light ochre and Cherokee red, so favored by Wright. This warms the rooms up and retains the cozy essence, despite being so open to the outside. The paint, just like many other items, was designed especially for Fallingwater by PPG (originating in Pennsylvania, the company quickly became a global player) to withstand the adverse conditions that existed right over the waterfall.

Wright appreciated that this was a summer house. I think it was precisely this personal purpose that made him design much of the furniture as built-in. Or, as he called it, “client proof”. Today, it is probably the only house designed by Wright retaining the majority of its original furnishings and decoration.

The family enjoyed the house for over two decades. On October 29, 1963, Edgar Kaufmann Jr. entrusted the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy with preserving Fallingwater.

Rarely does such a perfect storm of fame, patronage, genius, and controversy come together. It is no surprise that Fallingwater retains its iconic status, visited by over 4.5 million people since its opening.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!