Summary

- Images of pregnant women in traditional cultures

- Pregnancy representations through myth

- Pregnancy court portraits

- Moralizing genre or satire?

- Pregnancy in the modern era

- The beauty of pregnancy in contemporary art

Venus As a Symbol of Fertility

Images of pregnant women, especially small figurines, were made in traditional cultures in many places and periods, though it is rarely one of the most common types of image. These include ceramic figures from some Pre-Columbian cultures and a few figures from most of the ancient Mediterranean cultures. Many of these seem to be connected with fertility. Identifying whether such figures are actually meant to show pregnancy is often a problem, as well as understanding their role in the culture.

Venus of Willendorf, Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Photograph by jorgeroyan via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0).

Among the oldest surviving examples of the depiction of pregnancy are prehistoric figurines found across Eurasia and collectively known as Venus. The best known is the Venus of Willendorf, an oolitic limestone figurine of a woman whose breasts and hips have been exaggerated to emphasize her fertility. These figurines exaggerate the abdomen, hips, breasts, thighs, or vulva of the subject, but the degree to which the figures appear to be pregnant varies considerably, and most are not noticeably pregnant at all.

Damaged roman votive female pregnant figurine, Wellcome Collection, London, UK.

Greek Mythology

Titian, Diana and Callisto, circa 1566, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

In Europe, depictions of pregnancy were largely avoided in classical art, but later Western art had two subjects that were frequently depicted where the pregnancy was integral to the narrative: the unhappy scene usually called Diana and Callisto, showing the moment of discovery of Callisto’s forbidden pregnancy, and the biblical scene of the Visitation.

The nymph Callisto from Greek mythology was the favorite of Diana, the virgin goddess of the hunt. Her beauty aroused the attention of Zeus, king of the gods, who seduced her by disguising himself as Diana. Nine months later Callisto’s pregnancy was discovered when she was forced by her suspicious companions to strip and bathe after hunting. Juno, the wife of Zeus, then turned her into a bear. The few classical depictions tended to show this transformation, but in later art the traumatic moment of discovery was most often depicted, especially from the Renaissance onwards, using the Roman poet Ovid as the source.

What became the typical composition was first seen in Titian‘s Diana and Callisto (1559), where Callisto’s abdomen is exposed as Diana points accusingly at her. Although Ovid places the discovery in the ninth month of Callisto’s pregnancy, in art she is generally shown with a rather modest bump for late pregnancy. But this is appropriate, as the scene shows the moment when her intimate companions first realized that she was pregnant. It is clear that the main attraction of the subject was the opportunity to depict a group of female nudes, though it could be claimed that it illustrated the serious consequences of an unwanted pregnancy.

Maria Gravida

Rogier van der Weyden, Visitation, 1445, Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig, Germany.

Depictions of the Virgin Mary were by far the most frequent images featuring a pregnant woman in post-classical Western art, and probably remain so to the modern day. Unlike many other kinds of depictions of pregnancy in art, there is usually no ambiguity as to whether Mary is intended to be shown while pregnant, even where the pregnancy is not clearly visualized.

The Visitation, a meeting between two pregnant women—Virgin Mary and Elizabeth as recorded in the Gospel of Luke—was very often depicted, but their pregnancies are usually not emphasized visually, at least until Early Netherlandish paintings of the 15th century. Medieval thinking held that Elizabeth was about seven months pregnant at the meeting, and Mary was about one month pregnant. The loose full clothes used in religious art, as in normal medieval life, make it hard to detect in any case. In some cases, one or the other of these two women places a hand on the bump of the other woman, as in Rogier van der Weyden‘s Leipzig version above.

Master of Erfurt, The Virgin Weaving and the “cutaway” unborn Jesus, Upper Rhine, ca. 1400. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Antependium with the Visitation and two “cutaway” children, ca. 1410, Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Marx Reichlich, Meeting of Mary and Elizabeth, the first half of 16th century, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany.

A few images, mostly Byzantine or late Medieval German, show their unborn children in the womb, similar to modern cutaway drawings. In German images they are naked, and John the Baptist bows or kneels to Jesus, who raises a hand in blessing. It should be emphasized that, in all periods, the majority of depictions have little visual indication that either woman is pregnant; the story was well-known to its audience.

Other similar images, especially statues, are of Mary alone; these are called Maria gravida (Pregnant Mary).

Seated Expectant Virgin Mary (Maria Gravida), International Gothic, 1430-1440, Collection of Old Masters, National Gallery Prague, Prague. Czech Republic. Museum’s website.

Piero della Francesca, Madonna del Parto, Museo della Madonna del Parto, Monterchi, Italy. Visit Tuscany.

Madonna del Parto is an Italian term for figures of the Virgin Mary especially associated with pregnancy and childbirth, or showing the Virgin pregnant. These are not very common; the best known is the fresco by Piero della Francesca, where a heavily pregnant Mary has a prominent unlaced opening at the front of her dress, and another at the side. However, these depictions fell from fashion during the Renaissance, and Piero is the latest known from Tuscany.

A few of these images of Mary feature a cutaway view of Jesus in utero within, as found in some images of the Visitation, and many have the same protective gesture of the hand on the stomach, which also features in portraits of other pregnant women, when those begin to appear. After the Counter-Reformation, a visualized in utero Jesus becomes rare, and instead, Mary may be shown with the Christogram “IHS” on her stomach.

Baroque Maria gravida with the Christogram “IHS” on her stomach. Photograph by Fuchs01 via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0-AT).

Portraits

Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, National Gallery, London, UK.

In the Late Medieval period, portraits of pregnant-looking women began to be painted, though the fashion for dresses gathered at the front makes these difficult to interpret or identify with confidence. The Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck of 1434 might be an example of pregnancy in art, but the current views of art historians are mostly against this, as virgin saints were often shown in much the same way. The virgin martyr and princess Saint Catherine of Alexandria usually dressed in the height of fashion in this period—and was also the patron saint of childbirth—so there may be a degree of deliberate ambiguity in images of her.

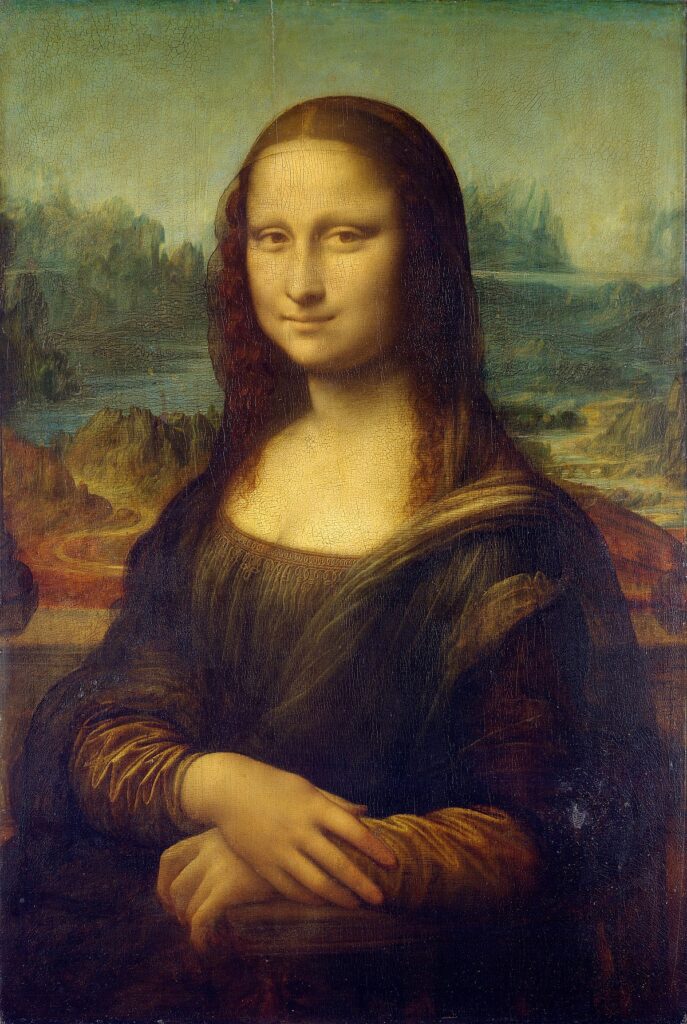

Some Italian Renaissance portraits thought to be of pregnant women show them wearing an airy underdress called a guarnello, often associated with pregnancy or the period after childbirth. These include Leonardo da Vinci‘s Mona Lisa, where the garment first became visible under infrared scans in 2006, suggesting that she was pregnant or just had a baby when she was painted. Another painting with a guarnello is Botticelli‘s Portrait of a Lady Smeralda Brandini where the subject also holds a hand over the top of her bump. This is a feature seen in many images, such as Visitation scenes, where pregnancy is certain, and that probably indicates pregnancy in cases where it is much less clear. La Donna Gravida (The Pregnant Lady) by Raphael is another example, with an apparently pregnant woman sitting with her left hand over her stomach, but such depictions remained infrequent in the Renaissance.

There are some earlier examples from court portraiture in Europe and mostly in England, but the main group of English portraits dates from roughly the late 1580s to about 1630. At around the same time as the English examples, Margaret of Austria, Queen of Spain sent portraits of herself while pregnant to close female friends and relations.

Her daughter, Anne of Austria, Queen of France, was herself painted when eight months pregnant with the future Louis XIV of France, born 23 years into her marriage. The portrait of their unfortunate cousin, Holy Roman Empress Maria Leopoldine of Austria, who died in childbirth at 16 in 1649, the year the portrait is dated, is perhaps a posthumous adaptation of her wedding portrait.

Rembrandt, Portrait of Oopjen Coppit, 1634, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Later portraits of pregnant women tended to be family members or at least friends of the artists; relatively few women, or their husbands, chose to commission expensive portraits (often only done once in a lifetime) showing them pregnant, although many women spent most of the early years of their married life pregnant. The most common moment for a woman to have her portrait painted was just after her marriage when any suggestion of pregnancy would be unwanted. In some well-documented cases, the subjects of portraits can be shown to be well into pregnancy when the portrait was painted, but this is suppressed or concealed in the image.

Moralizing Genre or Satire

Wiliam Hogarth, A Woman Swearing a Child to a Grave Citizen, 1729, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland.

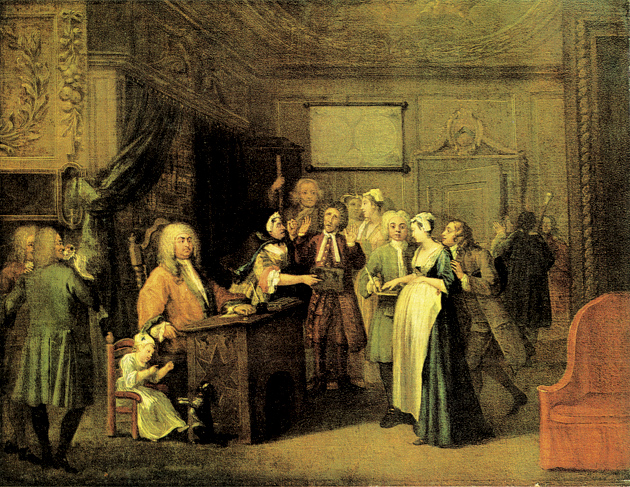

Some early modern depictions in genre painting or other media such as popular prints or book illustrations, addressed the social implications of pregnancy, either showing women who were seen as having more children than they could afford or women, especially maids, who had become pregnant outside marriage, with dire social implications for them. There are a number of narrative scenes showing unwanted pregnancies, essentially from the father’s point of view, including some where the woman has brought the matter before local magistrates to award financial support, as unmarried women were able to do in England.

The English artist William Hogarth included many pregnant women in his works, usually with a satirical or comic intention, and generally more often giving a negative implication than a positive one. In Hogarth’s A Woman Swearing a Child to a Grave Citizen, a young woman falsely accuses a rich old man of fathering her child, while the real father advises her.

Modern Era

Gustav Klimt, Hope I, 1903, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

Gustav Klimt, Hope II, 1907-1908, Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA. Museum’s website.

As the modern era approached, some artists began to show pregnancy in art more explicitly, with heavily pregnant figures and more pregnant nudes than before. Two paintings (not portraits as such) by Gustav Klimt Hope I (1903) and Hope II (1907–1908), show slim, heavily pregnant women in profile. In Hope I the figure is nude, and the pregnancy very evident, while in Hope II a huge and elaborate dress or cloak, reminiscent of the Renaissance guarnello, makes this less immediately clear.

In Hope II, Klimt depicts a woman looking down at her belly while three women rest at her feet, praying or possibly mourning. The decorative elements, in Byzantine style, introduce a marvelous relief on the painting’s surface. The viewer might notice an unsettling moment in the form of a skull nesting on the woman’s belly, reflecting on the emergence of psychoanalysis and Sigmund Freud’s explorations of the child within every adult, which took over Vienna at the turn of the century.

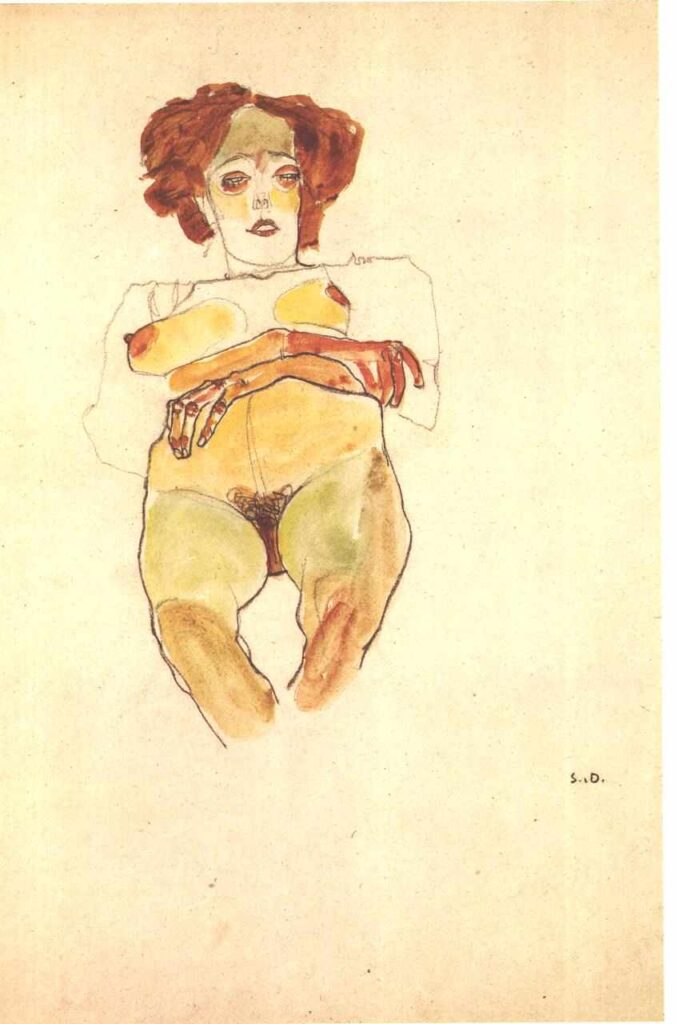

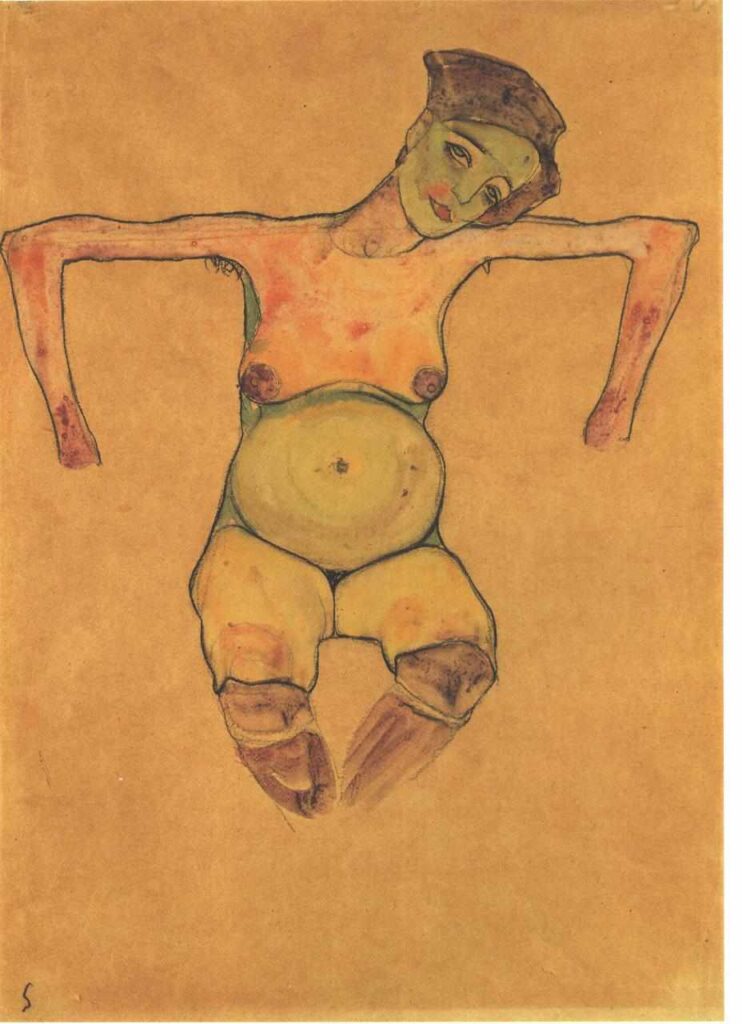

Egon Schiele made pregnant nudes the subject of many of his drawings with color, favoring a frontal view, and he created some rare paintings with the topic of motherhood as well. All the models Schiele drew were usually anonymous and served only to improve the artist’s drawing skills.

On the contrary, The Pregnant Woman (sculpture below) by Pablo Picasso was a sculpture dedicated to his then partner Françoise Gilot. Picasso wanted to inspire Gilot to have a third child with him by making this sculpture, but Miss Gilot apparently refused. It also stands as a sort of a fertility totem. Unfortunately for Picasso, his wishes did not come true, but in 2016, the work was featured in a groundbreaking exhibition of his sculptures hosted by MoMA.

Pablo Picasso, Pregnant Woman, 1950, Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA. Museum’s webiste.

The Beauty of Pregnancy in Contemporary Art

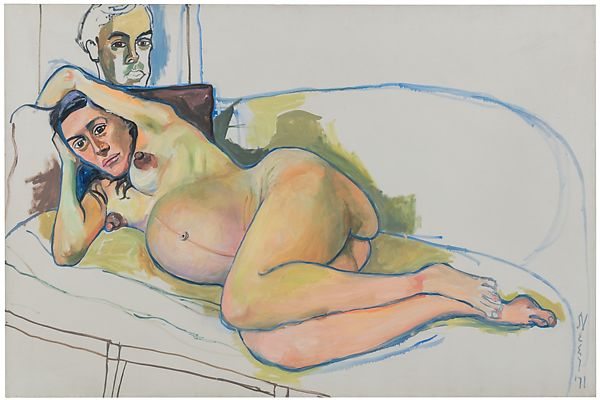

Alice Neel, Pregnant Woman, 1971, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. Museum’s website.

In the midst of the women’s liberation movement between 1964 and 1987, American artist Alice Neel painted a series of seven pregnant nudes. For the artist, the subject of generational renewal was interesting enough to portray it, resulting in five reclining and two seated nudes. Although she was never a declared feminist, her art certainly contributed greatly to the movement, and it also drew attention to the fact that pregnancy in art was never depicted by her male counterparts, even though “it’s a basic fact of life”.

In February 2016, Lucian Freud‘s 1960-61 Pregnant Girl (below) was the highlight of Sotheby’s London Evening Auction of Contemporary Art, having been sold for $23.2 million and thus setting a new record for an early painting by the artist. It was described as one of his most tender paintings, as it portrays his lover, then 17-year-old Bernadine Coverley, who was pregnant with their daughter Bella, now an internationally renowned fashion designer.

Lucian Freud, Pregnant Girl, 1960-1961. Sotheby’s.

Damien Hirst, Virgin Mother, 2005. Artist’s website.

Damien Hirst, Verity, 2003-2012. Artist’s website.

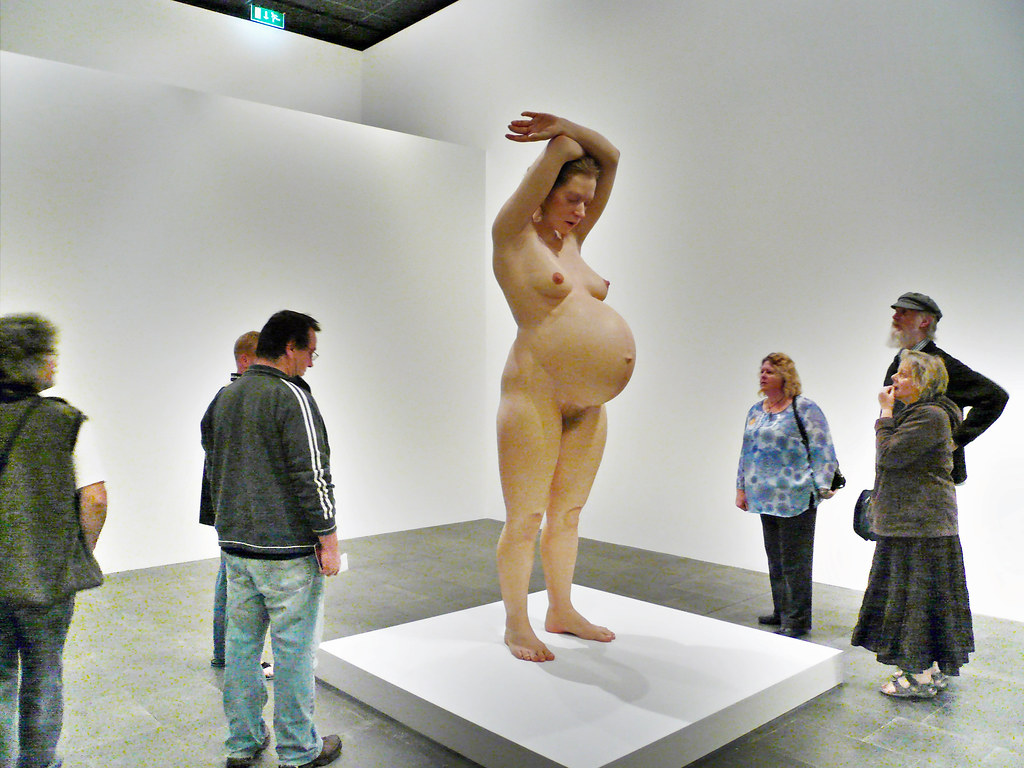

There have been nude sculptures of heavily pregnant women by, among others, Damien Hirst, with The Virgin Mother or his very similar Verity sculpture, or one particularly interesting by Ron Mueck. She isn’t real, but she looks incredibly so. Pregnant Woman is a 2.5-meter-tall sculpture of a naked pregnant woman clasping her hands above her head. Mueck spent about three months studying a living pregnant model and going through anatomical books, photographs, and drawings in order to achieve accuracy. And indeed, his sculpture appears to have recreated a woman carrying a child to the last detail. The work was on display at the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia, where it stood tall as a sort of a monument to motherhood, having the viewers confront pregnancy in ways they’ve never done before.

Ron Mueck, Pregnant Woman, 2002, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia. Museums’ website.

Marc Quinn, Alison Lapper Pregnant, 2005, Trafalgar Square, London, UK. Artist’s website.

This powerful, 15-tonne marble sculpture was one in a series created by Marc Quinn, dedicated to pioneering artist Alison Lapper who was born without arms. This particular piece was placed on Trafalgar Square in London. It aimed to demonstrate that disability is certainly not an obstacle to pregnancy, and it celebrated “a different kind of heroism” as seen in Alison Lapper. It also tackles both beauty norms of the Western cultures and the narrow binds of acceptability into which social norms tend to push us. Marc Quinn created a few other pieces of his model as well, one also featuring her son Parys.

Daniel Edwards, Monument to Pro-Life: The Birth of Sean Preston, 2006. Getty images.

To conclude our artistic path through all the variations of pregnancy representations in art, here we see singer Britney Spears, or better: her life-size sculpture in celebration of her first-born son Sean Preston. According to the artist Daniel Edwards, the Monument to Pro-Life honors the singer for “the rarity of her choice and bravery of her decision”, alluding to the fact Britney Spears choose family over her career at that moment.

The artwork became an emblem for Manhattan’s Right to Life Committee, essentially an anti-abortion group, and it also aims to provide inspiration to those struggling with the “right choice”.