The Vision of King Lalibela

The Kingdom of Ethiopia became one of the world’s first Christian nations when King Ezana of the Aksumite dynasty converted in the first half of the 4th century CE. This makes Ethiopian Christianity as old as Roman Christianity, and it predates the conversion of most European nations by centuries.

King Gebre Mesqel Lalibela (r. ca. 1181–1221), commissioned the rock-hewn churches in the 12th or 13th century CE. (Now named after him, the area was previously called Roha.) Legend tells that Lalibela had a dream in which God told him to build a new Jerusalem in Ethiopia. Supposedly, angels helped him fulfill his mission by carving all the churches for him within a single day.

Different parts of the Lalibela site recreate specific features of Jerusalem. One rock-hewn structure references the Tomb of Adam, the Biblical first man. In addition, the site has hills named Calgary and Golgotha, a stream named for the River Jordan, and olive groves supposedly planted with olives taken from the Garden of Gethsemane.

The desire to build structures that evoke Jerusalem was not unique to Lalibela. In the Middle Ages, it was fairly common throughout the Christian world to create such alternative pilgrimage sites for those who could not travel to Jerusalem itself. In Lalibela’s time for example, Muslim rule in Jerusalem made it difficult for Christians to gain access.

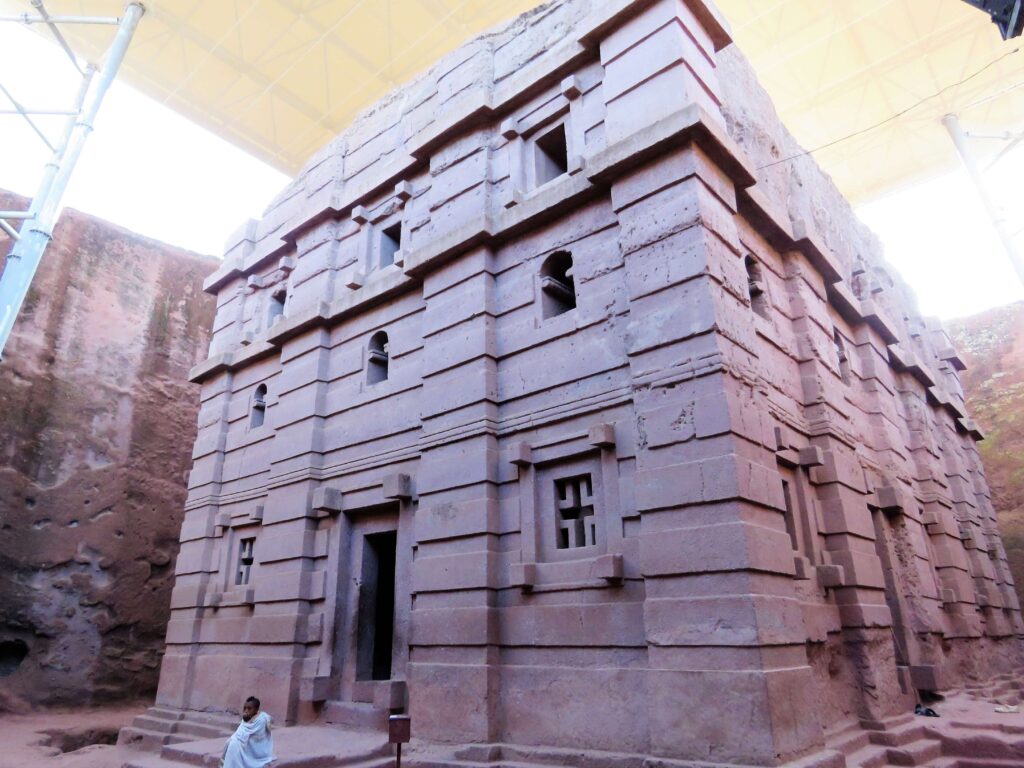

King Lalibela picked quite an unusual style of architecture in which to achieve his goal of an Ethiopian Holy Land. The Lalibela rock-hewn churches are more like sculptures than they are buildings. Typical buildings are constructed from the bottom up in a mixture of materials brought to an empty site. By contrast, creating the Lalibela churches required carving into the native rock already present on the site, working from the top down in a process of subtraction. Their creators essentially sculpted them like giant statues. The churches are monolithic, meaning that each consists entirely of one solid piece of rock. They do not contain seams, mortar, foundations, and other building materials.

Carving a Monolithic Church

The sculptors at Lalibela first cut downward to separate out the necessary block from the surrounding rock before refining the structure from the outside in. Some churches remain connected to the larger rock formation via one side or the top, meanwhile others stand independently. In all cases, vertical rock faces completely enclose the structures, with tunnels, ditches, and courtyards providing access and connecting the different churches. Accordingly, visitors’ approaches and lines of sight are highly structured, to dramatic effect. You can get a sense of it in a video that the World Monuments Fund has produced based on 3D laser scans. UNESCO also has a charming, animated children’s video about the site.

The Lalibela churches have been modified over time, and a few of them may have originally served other functions. Since altering a monolithic structure requires cutting away more rock, archaeologists cannot always get a clear idea of the changes.

Outside, the rock-hewn churches have very sparse ornament. They have some lovely arch and cross-shaped windows, either open or blind, arcades, and simple horizontal bands called string courses, but little else. This makes sense because their facades do not enjoy great visibility from afar. (From a distance, the churches remain largely hidden inside larger rock formations. People walk around the surrounding highlands roughly at roof level.)

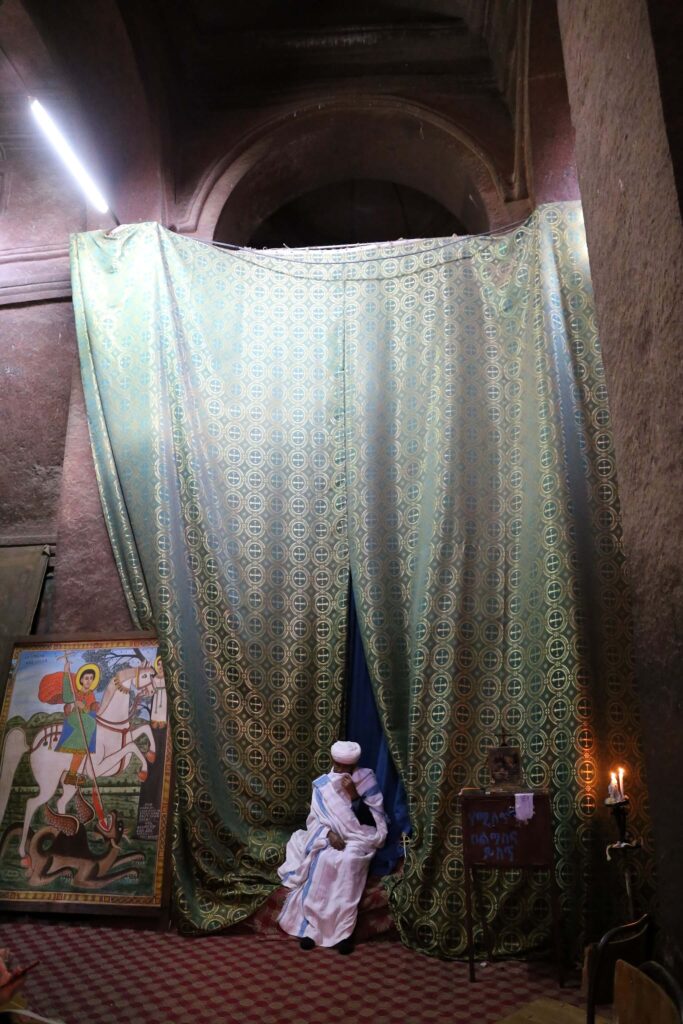

Richer decoration appears inside. Columns, arches, vaults, capitals, and window frames emerge from the same rock as the rest of the church. Carved and painted adornment, both figurative and abstract, have stylistic similarities with Ethiopian manuscript painting and also employ motifs from Aksum (an earlier Ethiopian Christian dynasty), the Islamic world, and the Coptic Christianity of Egypt. The churches further contain beautiful and precious liturgical furnishings.

Preserving the Rock-Hewn Churches

In recent years, a World Monuments Fund project has helped to conserve the Lalibela rock-hewn churches, which suffer from slow destabilization due to moisture and seismic activity. One of WMF’s first actions was to install giant, tent-like coverings (unsightly, but effective) to protect some the churches from further water damage. However, their very significance creates complications for their preservation. Owing to the longstanding association with angelic craftsmanship, every millimeter of rock has sacred status. Restoration specialists report priests gathering up the dust that fell from even the tiniest hole they drilled. Such reverence for the very fabric of the churches makes larger-scale interventions inappropriate.

The Lalibela Churches Today

There are other rock-hewn churches in Ethiopia – about 200 in total – but those at Lalibela are the most celebrated. The site is still important for Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, and the churches hold multiple services every day. Many people make pilgrimages there every year as well, often traveling a hundred miles or more on foot. At Orthodox Christmas in January, the site can receive as many as 200,000 pilgrims. It gained UNESCO World Heritage Site designation in 1978.

Ethiopian rock-hewn churches currently face a new threat – political violence ongoing in northern Ethiopia since November 2020. Rebel forces, who have already attacked other religious monuments, overtook Lalibela in the summer of 2021. No news (either good or bad) about the fate of the rock-hewn churches has appeared since them. Let’s hope all is well.