Francis Bacon in 10 Paintings: Flesh and Distortion

Francis Bacon stands out as one of the most renowned postwar painters. His trauma fueled his emotions, crafting a disturbing world filled with dark,...

Errika Gerakiti 18 November 2024

Today, historical Avant-Gardes are appreciated by every art lover, taught in every school, and worth millions of dollars, but it hasn’t always been this way. In 1904, when Avant-Garde art was taking its first steps, the businessman, critic, and art collector André Level took one of the greatest financial risks in art history: he founded La Peau de L’Ours, a speculative investment venture that purchased Avant-Garde artworks for up to ten years, establishing the economic value of this kind of art for the first time.

To understand why Level’s operation was so revolutionary we have to comprehend how the art system worked and changed throughout the second half of the 19th century.

In the first half of the 19th century, the only way an artist could succeed was by being accepted by the Académie des Beaux-Arts and the jury of the Paris Salon, which was mostly formed by academic members. There was little space for creativity and innovation as artists couldn’t even sell their works in their studios. One’s artistic career had to follow specific steps and artists had to comply with the institutional aesthetical canons.

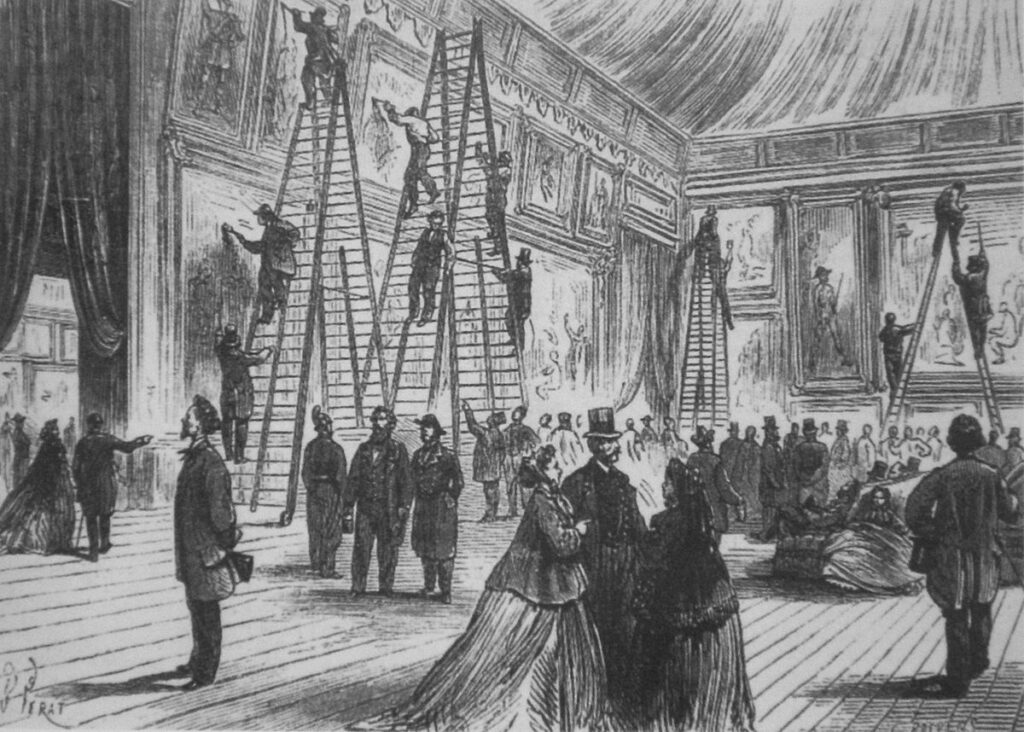

B. Perat, Vernissage au Salon, 1866. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

We can see the first signs of intolerance towards the institutional system starting to spread in 1855 when the artist Gustave Courbet opened the Pavillon du Réalisme. Here he exhibited many of his realist artworks, rejected by the official Salon.

From that moment many other Salons started to arise such as the Salon des Refusés, the Salon des Indépendants, and the Salon d’Automne. These were alternatives to the institutional Salon and promoted different kinds of art, opening up to a new public.

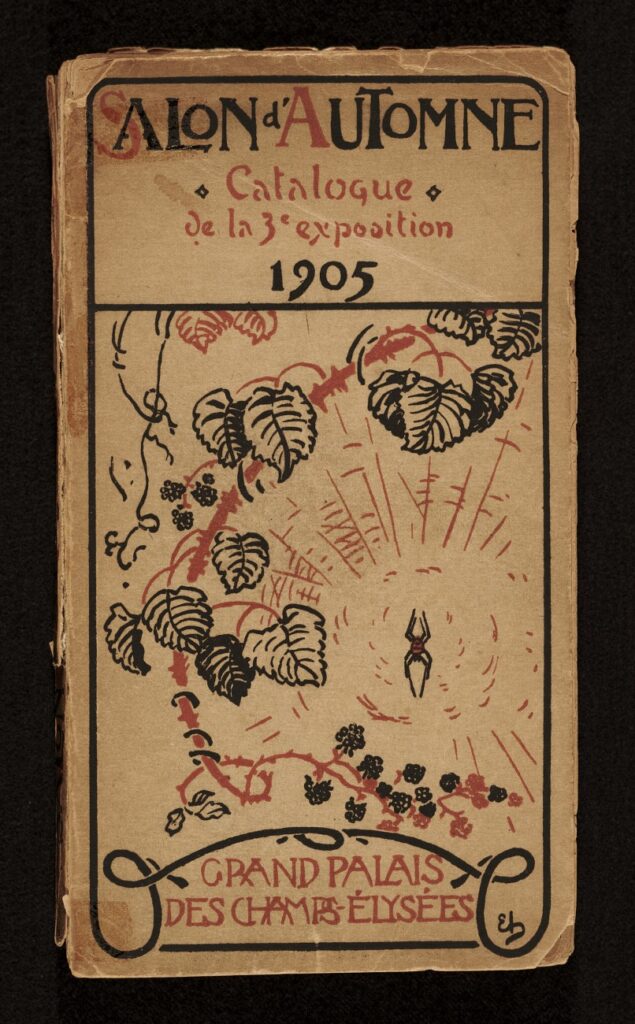

Catalog for the 3rd exhibition of the Salon d’ Automne, 1905. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA.

Thus, with the Impressionist movement at the end of the 19th century and the first Avant-Gardes at the beginning of the 20th century, the first illuminated art dealers stood out and structured what then became the Avant-Garde art market. These art dealers (Paul Durand-Ruel, Ambroise Vollard, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and Berthe Weill to name a few) innovated the art system by founding the first art magazines, organizing personal exhibitions, and creating an international network of galleries, art dealers, critics, and collectors.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, 1910, Pushkin Museum, Moscow, Russia.

At the beginning of the 20th-century Avant-Garde art was taking its first steps with the early works of the artists who would later be called Fauves at their first exhibition at 1905’s Salon d’Automne. Other movements and groups were springing up as well revolutionizing the art world within ten years, these include Cubism, Futurism, and, Abstraction.

André Level, a Parisian businessman and art lover, became fond of these new movements, frequenting the galleries that were promoting them and the Salon d’Automne. In 1904 he had a brilliant intuition. He realized that the artists and those who first admired them would revolutionize the art world, even if they were despised by critics and excluded by the official art system. That is when he decided to demonstrate the financial and cultural value of Avant-Garde art by founding La Peau de l’Ours.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of André Level, 1918. Artnet.

He gathered twelve people among his relatives and friends who were willing to pay an annual fee for ten years. He was the one in charge of the purchasing, which also had to be approved by at least one associate. They must have trusted him a lot because every year Level had 2,750 francs to buy artworks directly from the artists or art dealers and retailers.

The name of the association, which is French for “bearskin,” recalls the saying from La Fontaine’s fable, The Bear and the Two Companions, “don’t sell the bearskin before he’s dead”. In English it can be translated as “don’t count your chickens before they hatch”. It means that you shouldn’t count on what you don’t have yet, and alluded to the great financial risk that Level and his associates were taking.

The association was very important for the issue of the droit de suite (which could be translated from French as “the right of following”). This is the artist’s right to earn a share from the resale of their artworks. In France, the law of the droit de suite was only enacted in 1920 but was preceded by the foresight of La Peau de l’Ours, whose associates decided to give a 20% share of the income on the resale to the artists involved in the auction.

This decision clearly made the artists very happy and was also lauded by Apollinaire, the most influential art critic of that time.

At the end of the ten years, they had 232 works in all: 88 paintings and 144 drawings. Some of those artworks were made by a few of the most important artists and movements of the 20th century. There were 19 Nabis, 36 Fauves, 11 Picassos from the Blue Period and the Pink Period, as well as some Van Goghs and Gauguins.

In 1914 they presented and sold 145 lots at an auction in Paris at the Hotel Drouot and earned more than 100,000 francs. For example, Level sold a painting that is now known worldwide, Picasso’s Family of Saltimbaques, for 11,500 French francs, however he had bought it from the artist only for 1,000 francs!

Pablo Picasso, Family of Saltimbanques, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

This auction, which was also remarkable for its planning and advertising process, was one of the first events that made people understand that investing in new artists could be very profitable and that independent economical support was essential for the growth and diffusion of the new art.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!