This rare unification of the three works is the result of a masterpiece exchange program between two renowned museums. Displayed together, the works are an inspiring sight and pay homage to Manet’s provocative efforts to impart dignity to a class of people that are often forgotten and marginalized.

The Artist

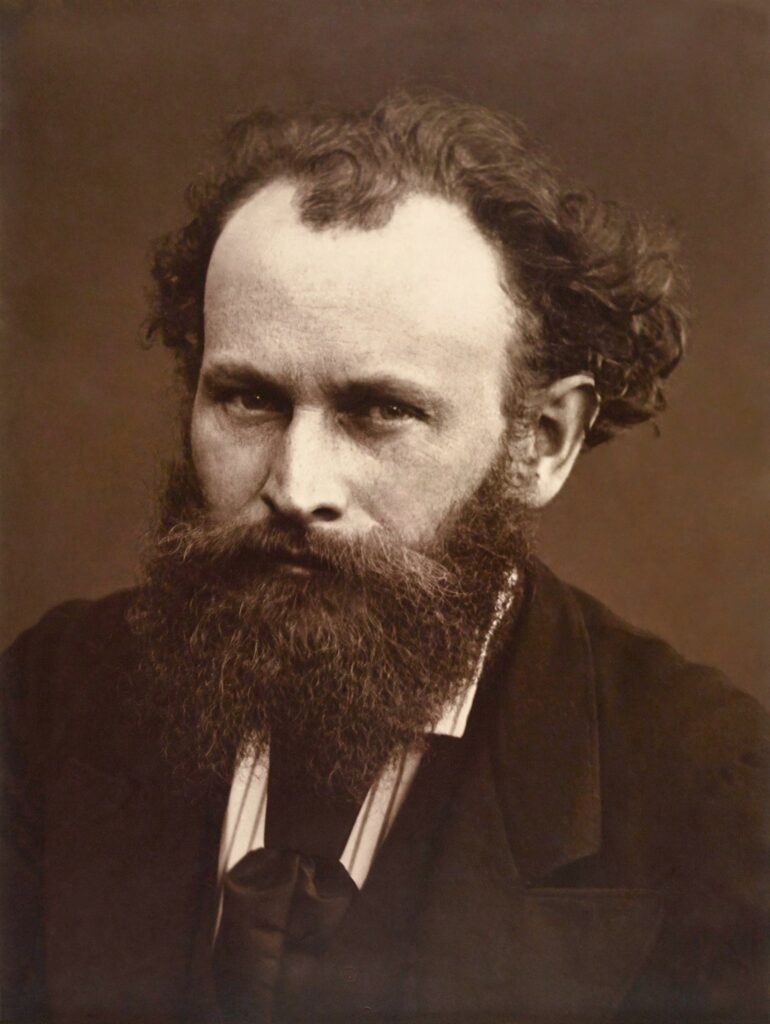

Édouard Manet‘s father was a high-ranking judge and his mother was the daughter of a well-connected diplomat. Despite Manet’s early interest and acumen, his affluent parents tried to steer him towards more respectable career alternatives that were better-suited to his means, such as a legal or naval career. However, after significant failures and setbacks, his parents acquiesced and Manet received the artistic training he sought.

Manet learned how to paint under the tutelage of Thomas Couture, who imparted him with rigorous academic standards. Early in his career, however, Manet rejected academic ideals in favor of bold brush strokes, implied shapes, and simplified forms. His innovative style was studied and admired by his contemporaries but was considered risqué. Manet is considered a prolific influence on the Impressionist movement and is also credited for leading the French transition from Realism to Impressionism.

Pursuit of the Paris Salon

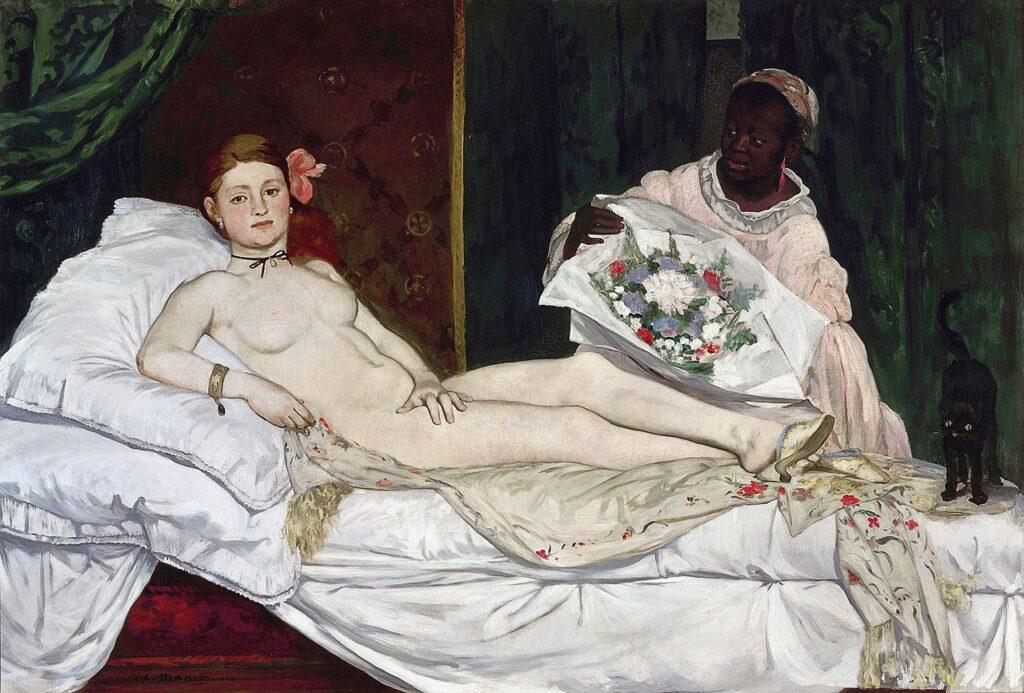

Manet achieved notoriety for his controversial works, Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe) and Olympia. The Luncheon on the Grass is a large oil on canvas painting. It depicts a rural setting with a female nude and a scantily dressed female bather on a picnic along with two fully dressed men. The casual nudity of the women displayed along with the clothed men out in a public setting was jolting to the academics. Thus Manet received a resounding rejection from the Paris Salon in 1863. It was subsequently displayed in the Salon des Refusés where it received a mixed reaction.

Manet’s painting of Olympia was, however, accepted by the jury members of the Paris Salon in 1865, though it caused an arguably bigger uproar among polite society. In the case of the Olympia, the nudity itself was familiar from the nude figures of the Italian Renaissance, however, the realism of the subject matter and the modern society they were portrayed in was still unsettling for the public sensitivities of the time.

Manet shared close personal relationships with the illustrious Impressionists of the time and his works were undoubtedly similar in style and subject matter, but Manet still rejected invitations to exhibit his works with the Impressionists. He remained a lifelong pursuer of the Paris Salon, yearning for it as a befitting home for his treasured works.

Spanish Influence

Manet traveled to Italy, Germany, and Spain to further his artistic training. During a trip to Spain in 1865 found himself profoundly moved by the 17th century works of Diego Velázquez. In his later correspondences with his friend, poet Charles Baudelaire, Manet declared Diego Velázquez to be the “greatest painter” there has ever been.

In 17th century Spain, there was a proliferation of romanticized depictions of the impoverished, particularly in portraiture. The single-figure “beggar-philosophers” Menippus and Aesop by Velázquez at the Museo del Prado in Madrid, served as the motivation behind Manet’s subsequent Philosophers. He adopted bold brushwork and sharp contrasts between light and dark in depicting these larger-than-life portraitures of poor and destitute men dressed in disheveled clothing, sometimes with still-life in the foreground.

Haussmann’s Renovation of Paris

In 19th century Paris, aggressive urban planning regulations were enacted that resulted in the large-scale destruction of medieval streets in favor of grand boulevards and open spaces under the prefect of Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann. This period, known as Haussmann’s renovation of Paris, unduly impacted the lower strata of Parisian society that were displaced en masse. The plight of these people who were driven into poverty and out of Paris was observed keenly by contemporary artists and writers, such as Édouard Manet.

Manet’s Philosophers

Manet’s Philosophers is a synthesis between two overarching themes: the humanistic “beggar-philosophers” inspired by Velázquez, and the lower strata of Parisian society that were displaced by Haussmann’s renovation of Paris. In these works, Manet draws on an age-old association between poverty and wisdom. He portrayed “beggar-philosophers” who were disadvantaged by their advanced age, crippling poverty, or perhaps, deteriorating mental health. Manet utilized full-figure canvases that would generally be reserved for portraits of the aristocracy or the wealthy to depict the indigent and sometimes intoxicated vagabonds, thereby imparting dignity to the overlooked and the forgotten members of French society.

Beggar with Oysters

This portrait by Manet is captivating due to the enigmatic expression of the beggar who stares directly and rather gently at the viewer. Manet expertly captures the beggar’s dignity here and successfully relayed the trope of the wise philosopher embedded in the social pariah. The sitter’s shabby attire does not take away from the wisdom and his eyes hint at great depth and a sense of knowing. The setting for this painting is bare with the exception of the discarded oysters apparent at the bottom right of the foreground.

Beggar with Duffle Coat

In this painting, Manet depicts an old beggar seeking alms. The subject faces the viewer with his hand extended to solicit donations. He is illustrated in a uniform-like attire, complete with a red beret and a cloak. During a conservation analysis at the Art Institute of Chicago, it was revealed that Manet made significant alterations to this composition over a two-year period. He widened the shape of the sitter’s head and added whiskers to his beard. The hand was also likely reconfigured since it originally curled upward and perhaps held something.

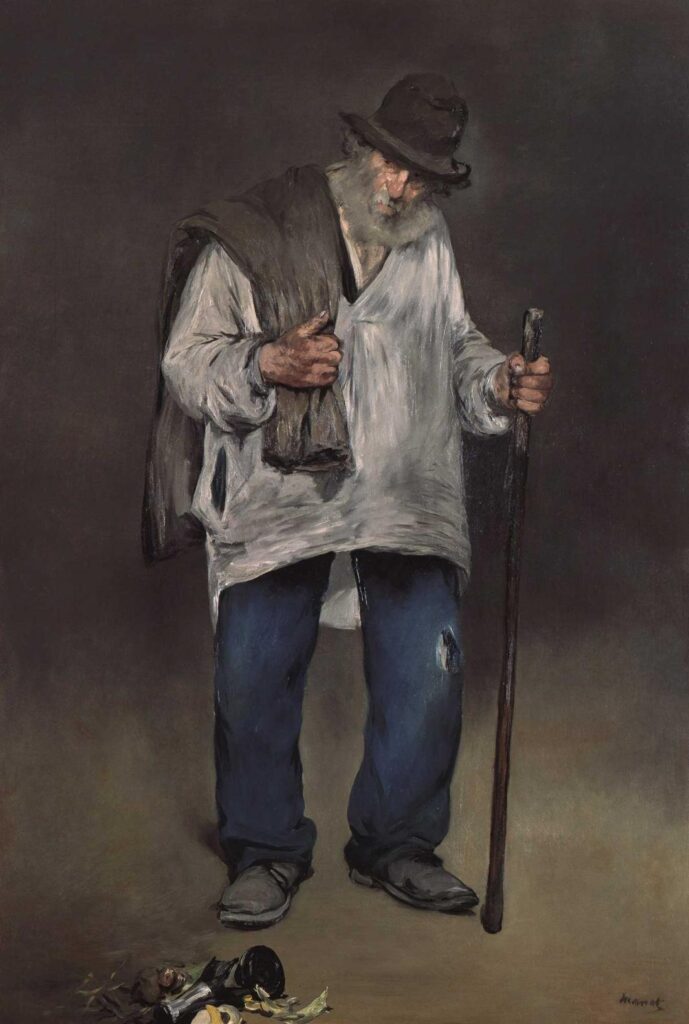

The Ragpicker

The Ragpicker is the culmination of the Philosophers series, depicting a frail old man supported by a cane. His clothing is worn from use and he has a satchel over his shoulder and trash before him. A ragpicker’s job, now obsolete in most of the world, involved scavenging through the garbage that was left out for trash collectors not just for rags, but kitchen scraps and any other items that might be salvaged or recycled. This profession did not reflect the truly destitute but did represent a class of persons who may have been alienated from the larger society. It is believed that Manet was drawn to them as he felt his own sense of alienation as a result of the rejection from established art circles.

The Fourth Philosopher

Although not a part of the current exhibit, The Absinthe Drinker (Le Buveur d’absinthe) is an early painting by Manet and was considered his first major painting as well as his first original work. In this piece Manet depicted a ragpicker named Collardet, who frequented that area around the Louvre in Paris. Manet portrays Collardet upright, leaning on the ledge behind him. Collardet is in a black top hat and is wrapped in a brown cloak, like an aristocrat. An empty bottle is discarded by his feet and a half-full glass of absinthe was later added on the ledge beside him. He does not share the bedraggled look of the other Philosophers.

The Absinthe Drinker was the first work that Manet submitted to the Paris Salon in 1859 and was rejected with only Eugène Delacroix voting in its favor. The absinthe may have been a part of the reason for its rejection, although the painting also has technical faults with its uneven finish, visible brushstrokes, and awkward placement of the legs in relation to the body.

The painting was acquired by the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen in 1914, where it is still held.

Exhibition Details

Manet’s Philosophers exhibit is the first time that Beggar with Oysters (Philosopher) and Beggar with a Duffle Coat (Philosopher) are being displayed in California. Don’t miss this great installation organized by the Norton Simon Museum, in the 19th century art wing through February 28, 2022.